Welcome to a new test series from Hagerty US, called The Death Eaters. With the help of the Lane Motor Museum and Kentucky’s wonderful NCM Motorsports Park, Hagerty is exploring the stories and real-world behaviour of legendary cars with infamous handling. The stuff of lore, common and obscure, from turbo Porsches to Reliant three-wheelers.

Let’s make one thing clear: We did not set out to roll the Tatra.

The purpose of this test was simple. In cooperation with both the Lane Motor Museum in Tennessee and Kentucky’s NCM Motorsports Park, we set out to chase the truth behind a few automotive stereotypes. The goal was to either give validity to stories of fantastical gore or pull the teeth from them. What began with a bit of research ended with a purpose-built skidpad course and a decreasing-radius corner at one of the country’s finest tracks.

In the middle, there was road time. Around 70 miles getting to know the car on public roads. The machine that revealed itself liked to slide with only a dust of warning – not particularly benign behaviour, in the modern sense, but not deliberately murderous, either. Picture a stretched VW Beetle with an air-cooled V8 up the breech. At the track, after some time on the skidpad, we paused for a safety check. The Tatra’s rear tyres were so stressed by the environment and the particulars of the car’s design that they nearly peeled off the rim. Personnel from the Lane museum suggested that we bump rear pressure for safety, and we agreed.

On the run after that, as I turned into a tight, first-gear corner, the car levitated.

Time ground to a halt. The driver’s window filled with asphalt. The car fell on its side with a crash and began grinding across the pad. Little chips of body filler sprinkled into my helmet as I came to grips with the fact that I had just rolled – was not even done rolling – a four-door, six-figure, apocryphally Nazi-killing Czech limousine.

A small stream of petrol drizzled out from beneath the car’s cowl and began dripping onto the road below. In the distance, on the other side of the pad, a handful of figures started running toward the car. Blurry motion, legs moving fast enough to avoid focus.

We had learned something, I thought. A lot of something. But first, I had a very strong urge to throw up.

Questions

At this point, the average reader should have two questions:

1. Why on earth was it so important for us to discover just how, exactly, a 73-year-old car was dangerous?

and

2. What in blazes is a Tatra?

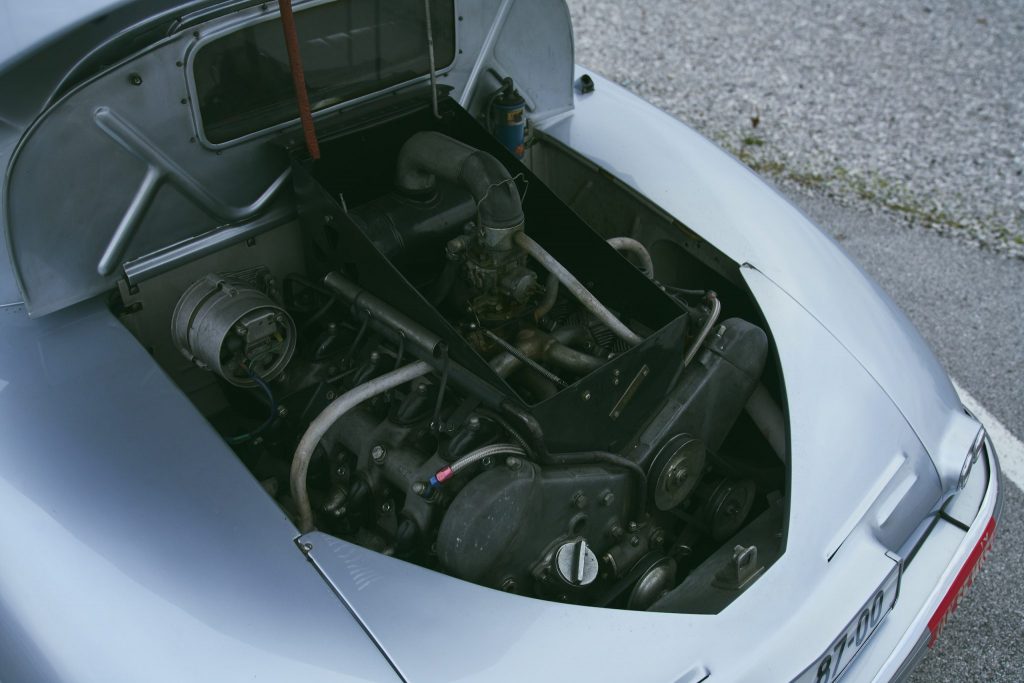

Answers in reverse order. The 1936-1950 Tatra T87 was the brainchild of an Austrian engineer named Hans Ledwinka. Extremely influential man, longtime chief engineer for Czechoslovakian marque Tatra, solid chance you’ve never heard of him. The T87 was Ledwinka’s magnum opus, a flawed but nonetheless lovely piece of genius that built and improved on his previous work for the company. At a time when most passenger cars offered the aerodynamic profile of a large cow, blunt and upright, the Tatra’s 0.36 drag coefficient helped it squeeze a top speed of more than 90 mph from just 75bhp. An air-cooled, overhead-cam, magnesium-block, hemi-chambered V8 lived behind the rear axle and drove the rear wheels through a four-speed transaxle, aiding traction and packaging. The car offered rack-and-pinion steering and independent rear suspension decades before either was common. Four adults could ride comfortably, six in a pinch. At 80mph, the Tatra’s interior was virtually hushed. In the 1930s, when most of the world was still trundling around in primitive automobiles only a few steps removed from tractors, such attributes were virtually science fiction.

Naturally, there were drawbacks. The T87 drove and suspended its rear wheels through swing axles, and swing axles of the 1930s were prone to strange behaviour in corners. The relatively narrow track was married to a relatively high centre of gravity. Finally, the Tatra’s front axle carried just 37 per cent of the car’s weight; the driver was miles away from the mass that helped compass the car’s moves, guiding a heavy pendulum at something like arm’s length.

Perhaps some of this sounds familiar. When Ferdinand Porsche sat down to design a German people’s car, the good doctor tracked a familiar path. Porsche had previously worked closely with Ledwinka and later admitted to “looking over his shoulder” while designing the prototype that became the Volkswagen Beetle. He was far from the only big name in the Tatra’s orbit, however. John Steinbeck owned a T87. King Farouk of Egypt loved the thing. Adolf Hitler adored it.

Enter the A-list piece of lore. Germany annexed Czechoslovakia in 1938. If legend is to be believed, so many Nazi officers subsequently died in one-car T87 accidents that the Wermacht Command eventually banned its soldiers from driving any Tatra at all.

Like all good rumors, that story took hold because the car’s reality supported it. Luigi Chinetti, the American Ferrari impresario and Le Mans winner, once told historian Karl Ludvigsen that a T87 felt like a cross between a Greyhound bus and a P-51 with a wing full of holes. According to Ludvigsen, a British trade society imported a T87 after the war and set about trying to parse its behaviour. The tests conducted found both vicious oversteer and such a “dangerous lack of stability” that the society’s test drivers flat-out refused to find the car’s top speed. The renowned British journalist Gordon Wilkins famously wrote that driving a T87 gave “the uneasy exhilaration which may be got from shampooing a lion.” Even today, some believe this is understatement.

The Lane museum is in Nashville. NCM, Hagerty’s track of choice for tests like this, is about an hour away, in Bowling Green, Kentucky. Early one morning late last year, I hopped in the Lane’s T87 in Nashville and drove to Kentucky. Twenty minutes into the trip, gliding down the highway at a serene 70mph, I fell into in an extended state of wonder, marvelling at the comfort and quiet. After 30 miles or so, the myth seemed toothless, the Tatra lightly particular in road manners but also mostly harmless, and certainly no more dangerous than an old Porsche 911. Then, near the state border, the draft from a passing truck sent the rear bumper into a series of uncomfortable and growing wag-the-dog oscillations across the lane. I let the big saloon have its head – attempting to correct for and chase those motions would have only made them worse – and after a moment, the car simply shook itself out. But the process consumed around an eighth of a mile of highway and produced the loudest eyebrow raise my body has given since 2015, when I had a wheel come off a Ferrari 488 in track testing and nearly liquefied my socks.

Hell of a car, I found myself thinking. A careful pair of hands on the wheel would be fine. And a distracted grandfather could probably crash the thing in a straight line.

Because history is nothing if not cruel, Ledwinka’s genius produced not fortune but footnote. When Tatra aimed infringement lawsuits at VW, Hitler shut them down. He also axed Ledwinka’s smart little Beetle competitor, the T97. Postwar, the Soviets jailed Ledwinka on trumped-up charges of collaboration. A subsequent VW-Tatra settlement sent the Czech company millions, but the man himself saw nothing. He died in 1967, more than a little bitter.

The story makes you curious. As to the relationship between reality and legend, but also the virtue of iconoclasm, and the power of time to calcify truths. And so, several months back, when Hagerty decided to spin up a series of tests focused on the intersection of infamy and myth… well, let’s just say we knew exactly where to start.

Roll me over, Ledwinka

I sat there, blinking back shock, as they pushed the car onto its feet.

Anyone familiar with YouTube and cars knows rollovers usually make their chain reactions visual: A sliding race car digs a wheel into the dirt, say, or a rally car hits a culvert and kick-flips onto its roof. Our rolling Tatra gave none of that logic when it went, merely a feeling of inevitability. I entered the corner at maybe 20mph. The same corner, a slow right-hander, that the Tatra had seen multiple times that same day, at the same speed and steering input. I turned the wheel at a rate and amount that had all morning produced a slow slide. Then my stomach went hollow.

Steering pad testing resembles autocrossing but is different. The discipline uses a vast expanse of pavement and occasional cone courses to chase cause and effect – watching the result of a mid-corner throttle lift at increasing speed, for example, or observing how a compressed suspension reacts to abrupt brake input. You keep the variables as stable as you can, and you plan long and change things slowly, especially in cars with dark reputations.

The morning had gone well so far. I was interested, albeit wary, when the Tatra began to slide its rear tyres in testing. The car was uniquely odd in a hundred ways but controllable, even predictable, once you learned its habits. We tried big slides and shorter ones, quick steps out and longer dramatic arcs, and the rear tyres returned to grip either abruptly or gradually, depending on momentum and how much leash you were willing to give the helm. Above all, the engine’s mass and the rear suspension gave a domino effect in corners – once the Tatra’s substantial mass began moving in a given direction, the tail was following come hell or high water, even if the driver changed his mind. So long as you avoided trailed brake (the rear suspension would jack and hang) and kept your foot deep in the throttle (lifting in a corner transferred weight in a way that took acres of road to fix), the car seemed almost docile.

In short, like every vehicle, the Tatra lived by a set of rules, if unique ones, and those rules had consequences. Picture the Queen Mary on a toboggan: fun, after a fashion, but you shouldn’t buy a ticket without being well aware of the forces at work.

Just less vintage than they expect

Imagine a car with a small building on its bumper. Now imagine rear suspension that can turn its tyres nearly horizontal.

Shortly after this test concluded, I was talking with a racing friend from Chicago. The rollover struck him as inevitable. “Any engineer will tell you that thing will roll immediately, if you do that, given anything like a modern tyre.”

The Tatra wasn’t on modern rubber, but it wasn’t on vintage tyres, either. More an in-between. The 185-section Michelin Xs on the Lane’s T87 are a current-day reproduction of one of the first mass-produced radials, a French design more than 50 years old. The X is a widely respected standard in the classic-car world, and calibrated to produce something like midcentury grip. (Translation: Slap the same tyre on a new SUV, you’ll be sliding 20mph below the speed limit.) The T87, however, was designed before the advent of radials and originally intended for crossply tyres. Less grip there, and different sidewall behaviour to boot.

As one of our support crew at NCM remarked, “It’s not that the Michelins are modern tyres. They’re just less vintage than the car was designed for.”

Now consider those swing axles. Picture the layout in its simplest form – a simple form of independent rear suspension, basically a solid axle with a hinge in the middle, so the wheels can “swing” up or down in travel. Compress that suspension, you get substantial camber loss – the geometry of the axle causes the tyre to tilt substantially inward at the top. Let the axle go into droop, however, and the tyre gains positive camber – it leans outward as the axle progresses down, as if the wheel were trying to wedge itself under the car.

Tyres like to be upright, and they like predictable treatment. Swing axles care about that stuff roughly as much as car magazines care about the zeppelin hobby. The layout isn’t inherently dangerous, especially if a car’s construction physically limits the axles from moving too much, but the fringe behaviour can be troublesome. After World War II, no less an engineering might than Mercedes-Benz aimed significant effort at solving the problem of swing-axle geometry, but even they eventually gave up and moved on. Ledwinka did what he could given his resources and priorities, but that wasn’t really much. The Tatra didn’t like gross attitude changes at any point, and it could seem recalcitrant, simply unwilling to shift mood once committed. As testing progressed, the rear axle’s behaviour left us concerned about what would happen if one of the intensely stressed Michelins separated from the rim. After Lane personnel added five psi of pressure, I did a loop of the skidpad to feel things out.

The result was a shouting testament to how a vehicle’s suspension is the sum of its parts, and how engineers choose spring and damper rates to work with a given amount of grip. The added pressure allowed the tyre to hold its shape more in corners, and the resultant added traction gave enough additional body roll that the Tatra’s inside wheel would hike a little and spin under power in corners. Emergency manoeuvres were less consistent and made me more uncomfortable, so we proceeded with caution. The next run, when I went to initiate a gentle, first-gear spin – essentially a slide uncaught, no steering correction – the car went over.

The simple answer is that the lower pressure let the Michelins deform enough to approximate the behaviour of crossply rubber. Regardless, when the outside wheel went into compression, the newly compressed axle acted as fulcrum. The car’s mass simply pivoted around it, and up she went.

Jeff insisted the show should go on

The folks at the Lane will tell you that some people on the museum’s staff dislike driving the T87 because it’s so different. Even given the accident, I found the thing remarkable. Highway driving is like standing on the prow of a ship, acres of substance behind you. Traffic is like being rolled around in comic-book mad zeppelin science. Valvetrain thrum and gearbox whine emanate aft. The engine sounds industrial and gruff, happiest around 3000 rpm, a relic from the time when large engines were attractive mostly because they were torquey, which was handy because most people and gearboxes hated shifting. The four-wheel drum brakes are unassisted and take all your leg to accomplish very little. Opening the windows at 75 mph gives zero buffeting. You nudge that deliciously light steering, surrounded by a nearly tangible sense of genius and wondering why the world became allergic to dreaming big. The sum experience recalls a 1960s American car turned inside-out and built decades before its time, for an Art Deco future that never happened, one where we all own flying boats and everyone has an extensive collection of steam-powered pants.

How many objects of industrial design seem to exist alone, absent equal?

“It was a limousine,” Jeff Lane told me, after the rollover. He gave one of those what-can-you-do shrugs. “It’ll go around a corner faster than you think it should, but it wasn’t designed to be driven like this.” He’s not wrong. The unfortunate catch, of course, is that people did drive it like that, and a reputation solidified, and there you go.

The arc of the 20th-century automobile is primarily one of speed and comfort. Driving evolved from a task requiring specialised mechanical knowledge to a pastime for the masses. We take it as a given that each new car gives more notice as to its intentions and fewer penalties for poor choices. But that arc goes hand in hand with our perpetually evolving definition of risk. In the early 1960s, when my father was a boy, my grandparents let him ride, unbelted, on the package shelf of their Pontiac Star Chief. Once upon a time, brakes that faded into nonexistence in normal traffic were simply as good as it gets. We accept so many ideas as destinations right up until the moment that hindsight proves them a brief stopover.

With the car back on its feet, I climbed out and lifted off my helmet. The padding glistened with sweat. One of NCM’s medics gave me a checkup, and then I sat down next to the car. The Tatra’s damage resembled a minor sideswipe, missing paint and dents. Hagerty’s staff filed an insurance claim, and I asked Lane if he wished to abort our test. Because he is a cheery man with no small amount of spirit, he insisted we keep going.

Ledwinka did as well. The T87 was not his last work, but the car’s strange blend of success and failure was so potent that it began to define the man’s legacy long before he died. By any cold metric, the Tatra was a dead end, if perhaps one slightly less than deserving of its reputation. And if history tends to focus on mistakes, well, it’s only because we are only worse off if those moments keep us from learning.

In times like those, we stand back up, and we take a breath, and we try to focus on the volume of what we don’t yet know. The nature of curiosity and failure. The reason why we bother solving problems in the first place. And why it is always, above all, best to never assume that you know an answer before the question has had a chance to leave your mouth.

1947 Tatra T87

Production: 1936-1950

Engine: 3.0-litre V8, 75bhp, 112lb ft (torque estimated)

Transmission: 4-speed manual

Drive: Rear

Weight: 1370kg

Known For: Attempting to invent the future and (possibly) killing a lot of Nazis.

The Reality: Not so much dangerous as demanding of attention, and unforgiving of coloring outside the lines.

Lesson: A formidable work of genius, in every sense of the phrase.

This is a really interesting article and serves as a timely reminder of just how crucial the right tyres can be. I am glad that no-one was seriously hurt in the process of showing just what can happen in the wrong circumstances.

It is worth noting that radial tyres are less camber sensitive at very small deflections but, as you observed, once those limits are transgressed the loss of grip can happen suddenly. How many classic car owners care more about what’s cheap, long-lasting or simply available in the right size; instead of trying to get the tyre that allows the car to perform as intended?

That said, a Tatra (ideally a 603) is one of those cars that I would like to drive before I die. Although I would like the time gap between the two events to be as great as possible.

I have personally conducted a moose test on a Tatra T87. I took one look and said “Yes, it’s a moose.”

In the 1950’s when I was in the motor trade after road testing various cars for brakes etc on the road after a service, ( no rolling road in those days) Hillman’s , Austin, Standard, etc, I frightened myself to death when I took a VW Beetle out for the first time, I came to the conclusion it was an accident waiting to happen, ok until you needed to turn a tight corner at anything other than 30 mph.

Very interesting, and just goes to show how important those four pieces of rubber are to your safety. Another thing about the tyres fitted not only are they a modern type to act like cross ply / radial, but the compound used in modern tyres is nothing like the pure rubber tyres of the 1930’s – the grip factor, tread design ( possibly a big deep square block type) also modern tyres have weight and speed ratings all of which need to be taken into account when fitting modern tyres to a classic. As someone who restores classics I find this only too often, after people have replaced their tyres and find the car doesn’t handle like it did only to find totally the wrong rated tyres fitted then you have explain yes thay are the right size just not for that car!. Case in point – a car came in which should have tyres rated 77 H (light weight car 130mph) but had been fitted with 89 Y ( heavyweight car 190mph+) driver found it didn’t handle in the corners or in the wet. Then you have to explain that there is nothing wrong with the car, it’s just that the new expensive tyres are no good for that car. Please remember it’s not only the right size that matters when fitting modern tyres to a classic but also weight and speed ratings.

Seems like a simple strap to limit swing axle angle would stop this behavior before catastrophe occurs, or maybe not?

Worth knowing is that the 1930’s/1940’s German highways had on ramps and more importantly off ramps that had really tight curves. I don’t know if there are any interchanges left that haven’t been rebuilt, but as late as in the 00’s there still were some of those curves in the former East Germany, tight enough to be signposted 40km/h and that was really the highest speed you could somewhat safe and comfortably drive at. Originally the surface of the ramps seems to had been stones which would had made them more unpredictable than a modern asphalt road surface. So if the T87 tipped over at 20mph = 30km/h with well inflated modern tires, it seems possible that it could tip over at 40-50km/h with the old style crossply tires. I bet the driving schools didn’t teach you about speed blindness in the 1930’s/1940’s which might had made things worse.

you idiot you rolled a 75 year old tatra for nothing look at that poor thing!!!!! it wasn’t ment for going on tracks it was ment for speed

DOSE ANYONE CARE THAT IT WAS ROLLED!!!!!!!!

y don’t you roll a leaf i’d like to see that

Ever seen a front engine triumph Spitfire/GT6 rear suspension do a similar thing ?

It’s a long feature, but we recommend you read it in its entirety to understand the motive, and the context, for how the car rolled. It is worth noting though that neither a Spitfire, nor the 911 you mention in an unpublished comment, would fall over at only 20mph.