This story first appeared on Hagerty US on 18 October, 2018.

“The right crowd and no crowding,” was the tagline for Brooklands, the world’s first dedicated motor course. Built in just eight months, the 100-foot wide, 2.75-mile banked track in Surrey, first opened on July 6, 1907, when an estimated 13,500 spectators arrived by train, car, and even horse-drawn carriage. What they witnessed was a variety of race cars including long-lost car marques such as Ariel Simplex, StrakerSquire, Darracq, and Minerva, and some not-so-lost, such as Fiat and Daimler.

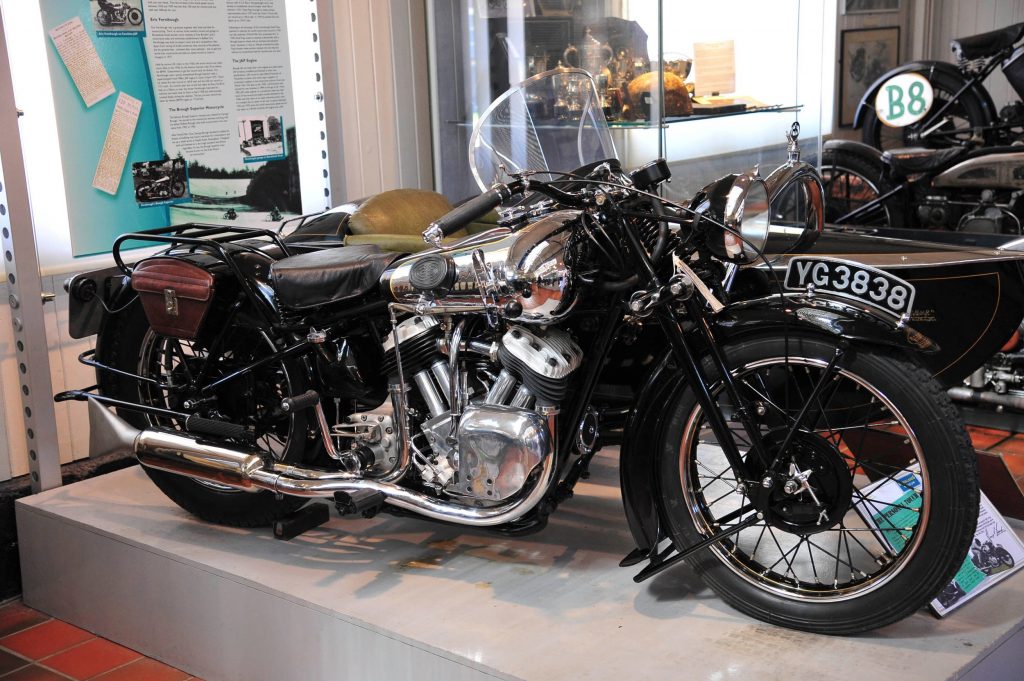

Today there is also a spectacular museum, where you can immerse yourself not only in Brooklands’ motor racing past, but also its history as a centre of aircraft testing, research, and manufacturing.

Drivers were the bravest and the most skilled of the day. Names like Henry Tyron, Charles Jarrott, and Selwyn Edge drove enormous open-bodied steeds. And if the banking was scary (which it was), they only had themselves to blame, since the previous year those drivers had been consulted by circuit founder Hugh Fortescue Locke-King and his enthusiastic wife, Ethel.

The beginning of Brooklands

With £150,000 of their own money – today about £17 million – the star-struck Locke-Kings proposed to build a specialised motor circuit at their Brooklands estate. They hired two talented engineer/designers and an initial workforce of 300 labourers, along with steam diggers and wagons, to lay a track through the woodland and scrubby marsh alongside the main Portsmouth-to-London railway line and the River Wey. The work was considerable and at times there were nearly 2000 men on site clearing 30 acres of trees, shifting 350,000 cubic yards of soil, cutting through a hillside to make one banking, and then raising the ground 20 feet for a mile-long Southern banking, just opposite of where shoppers now heave their groceries into their cars at a Tesco supermarket.

They spanned the Wey with a seven-arch Hennebique ferro-concrete bridge, built 75 paddock stalls, a substantial clubhouse, 28 garages, and raised 5000 spectator seats. This was truly the birth of closed circuit motor racing. It was home to vast speed record breakers, and firms that built and maintained them such as Thomson & Taylor, plus a gathering place for socialites of the day, such as romantic novelist Barbara Cartland, and haunt of the best drivers.

But because automobiles are only half the story, when you call Brooklands today, the cheery voice of race driver and TV personality Tiff Needell proudly welcomes you to “the birthplace of British motorsport and aviation.”

It was in 1908 that Alliott Verdon-Roe carried out the first taxiing and towed flight trials, and on October 9 the following year, Louis Paulhan made the first official flight at Brooklands in his Farman biplane in front of over 20,000 spectators. Stick that in your pipe, race-car drivers.

Home of aviation

By 1910 Brooklands was the site of a variety of flying schools, including that of airplane manufacturers Bristol, Vickers, and, two years later, Sopwith. In 1915 Vickers set up a huge airplane factory at Brooklands, and 100 years ago, at the onset of the Great War in 1918, the site was Britain’s largest aircraft manufacturing centre with many developments dreamed up, designed, and built there, including Marconi’s work on the first air-to-ground radio systems.

The airfield was used for the development and production of civilian aircraft between the wars, and in 1939 it (again) became a centre for wartime aircraft manufacture, accounting for a fifth of all the Hawker Hurricane fighter and Wellington bombers built during hostilities. After the war the site became crucial to the development of civil airliners. Vickers designed and built the Viking and Viscount there, and in 1960 Brooklands became the home of the British Aircraft Corporation – more of the Concorde supersonic airliner was built at Brooklands than anywhere else.

The Brooklands Museum

The history of Brooklands’ active years, which runs from 1907–88, is complex and diverse. These days the Brooklands estate has been split up and built on, with various residential developments on the outfield and industrial and retail parks, along with corporate headquarters, on the infield. Mercedes-Benz World owns part of that infield and the old circuit’s Railway Straight, which it uses as a conference and driving centre with a hotel and small grass airstrip attached. Across the river sits its neighbour, Brooklands Museum, which attempts to document and celebrate this complex automotive and aeronautical past.

“It’s a 33-acre site,” says newly appointed chief executive Tamalie Newbery, “and most of it is a scheduled ancient monument. Not many 20th century things get to be scheduled as such, but the racetrack is. We have five listed buildings on site, and of our total of about 20 buildings, most have some form of historic interest.

The litany of amazing exhibits is extraordinary. Besides the looming presence of the track itself, there’s Barnes Wallis’s Stratospheric Chamber, designed to study the effects of high altitude flight; Delta Golf, the first Concorde jetliner to carry 100 passengers at Mach 2; R for Robert, the World War Two Wellington bomber ditched in Loch Ness; Z2389, a Hawker Hurricane Mk.IIA, which flew with the American volunteer 71 Eagle squadron; and the Grindlay Peerless, Brooklands circuit 105-mph lap-record holder.

A particular favourite of mine is John Cobb’s 1933 Napier Railton; all 16-foot-3, 24 litres, and two long tons of bare-metal finery. Purchased by the Brooklands Museum in 1997 with Lottery funds and help from a number of individuals, this extraordinary car seems to epitomise a bit of the Brooklands story.

On October 7, 1935, Cobb drove the aircraft-engined behemoth and lapped the banked circuit, including the infamous bump, in 69 seconds, setting a perpetual outer-circuit lap record of 143.44 mph – what a brave man he must have been. “You don’t need to care about engineering, or cars, or planes to be absolutely captivated by the determination, grit, skill, luck, and sheer daring of people that did things here,” Newbery says.

A more recent star is the new £8 million Aircraft Factory where you can not only see some of the highlights of the museum’s aircraft collection – though the marvellous Vimy World War 1 bomber sits aloof in its own shed – but can also design and build your own take-home model aircraft on modern tools designed for exactly that (I’ve still got mine).

The future of the Brooklands Museum

So what’s next on Newbery’s books?

“The aircraft factory has been the largest project the museum has ever done and it’s been all-consuming,” she says. “With that done and the change in senior leadership, we are taking a year or two to consolidate and deal with a backlog of things. I think people have, for a long time, had lists of projects that would improve the interpretation, the site, and the conservation.”

Further site clear-up and clear-out is on the cards, although Brooklands has been much titivated over the years since it appeared to be a dumping ground for worn-out aerodrome equipment.

“We are a semi-industrial site,” Newbery admits, “and some parts of the museum are extremely attractive and just lovely environments, but other bits are quite post-industrial, and in the middle of the winter when it’s sideways rain, they can feel a bit bleak. We have to really make sure that we put enough into the experience that is comfortable and attractive.”

She’d also like some hard standing for the aircraft park and to do more to promote the role of women in the early days of the circuit, including Ethel Locke-King (her car is in the museum) and racing drivers such as Gill Scott, Joan Richmond, the Honourable Mrs. Victor Bruce, or Kay Petre. She also thinks that Brooklands has a role in encouraging women into engineering.

“In the end, there’s not the funding to do [these things] right away,” she says. “And we need to build up the story and think about the pay off for the things that are urgent because they’re falling down or at risk, versus the things that will do most to help drive up the visitor numbers to make things sustainable in the long run.”

It’s that continual search for funding that dogs big museums like Brooklands, although the London Bus Museum which shares the site (and the gate money) has helped to push up visitor numbers in recent years, as has the Concorde and the Aircraft Factory. And Newbery’s background in museum administration and fundraising should stand her in good stead.

For the moment, however, it’s time to enjoy and take stock; Brooklands is already shortlisted for this year’s Arts Fund Museum Of The Year.

Besides, irrespective of who’s at the head of it, this is one museum with a joyful and chaotically bustling life of its own. Car rallies vie with meetings, talks, workshops, and motorsport events all the days long. I catch glimpse of a flier for the night-time Brooklands ghost walks and the Concorde experience with a “flight” in the genuine pilot training simulator.

And then there are the days when they fire up Cobb’s old Napier Railton. It speaks for itself really. You just need to be there.