“They don’t make them like this anymore.”

How often have these words been pronounced around a classic car? Yet, what usually amounts to nothing more than a casual observation becomes much more poignant when the classic car in question is a Mercedes-Benz.

Whether its cars really were better 30 or 40 years ago may be up for debate, but there’s no denying that Mercedes-Benz once took itself and its place in the world much more seriously than it seems to do now.

This was a time when Benzes often weren’t the fastest or most impressive cars you could buy, yet they were almost always the most expensive. That pricing power, of course, stemmed from the impeccable reputation for engineering integrity the company used to enjoy.

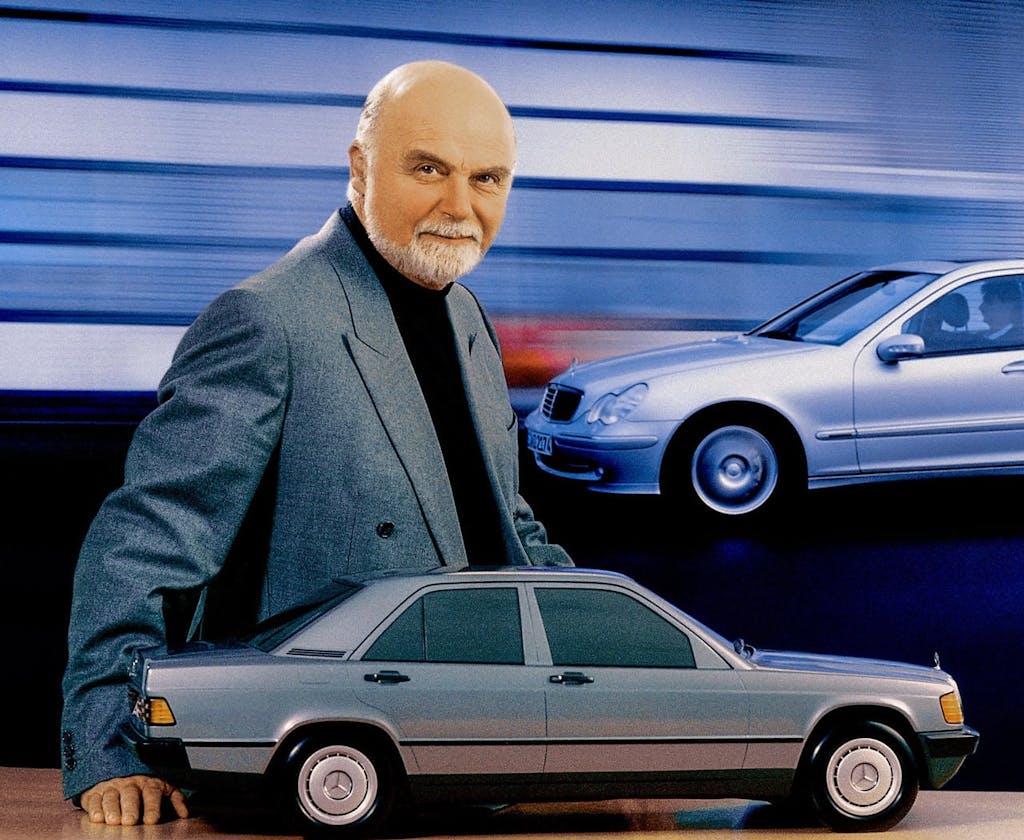

But even when Mercedes-Benz vehicles weren’t the best in their class, their appearance alone conveyed an aura of superior quality. And that was largely thanks to one man’s vision: the legendary Mercedes-Benz design director, Bruno Sacco, who passed away on 19 September at age 90.

After a brief spell at Ghia in Turin, Sacco joined Mercedes-Benz’s design department in 1958. In later interviews, he said that what drew him to Stuttgart was his fascination with the 300SL “Gullwing” and the racing successes of the W196 “Silver Arrows” Formula 1 cars.

Over the following years, working under Friedrich Geiger and Karl Wilfert, the young Italian absorbed Mercedes-Benz’s engineering-led design approach while growing a deep, genuine appreciation for his adopted country’s culture. German is a notoriously tricky language, yet he reportedly mastered it to a level that would put many natives to shame.

Nevertheless, when Bruno Sacco took over the reins of Mercedes-Benz’s design department in 1975, he had his work cut out for him. The company was in fine shape from a financial standpoint, but the oil crisis and ensuing CAFE regulations in the all-important U.S. market posed a significant threat to its business.

In a world of dwindling resources, the answer for the next S-Class (codenamed W126) couldn’t simply be “more” of everything. Mercedes’s flagship for the 1980s had to deliver all its predecessor did and more while being substantially lighter and more aerodynamically efficient.

It was a daunting task, yet the new generation of the S-Class, presented in 1979 and the first design for which Sacco was fully responsible, delivered on all counts and then some. The W126 sedan looked more svelte and athletic than the outgoing W116 while losing none of its presence and panache. Sacco’s team struck a perfect balance, creating a classic for the ages that, to this day, remains the most successful S-Class of all.

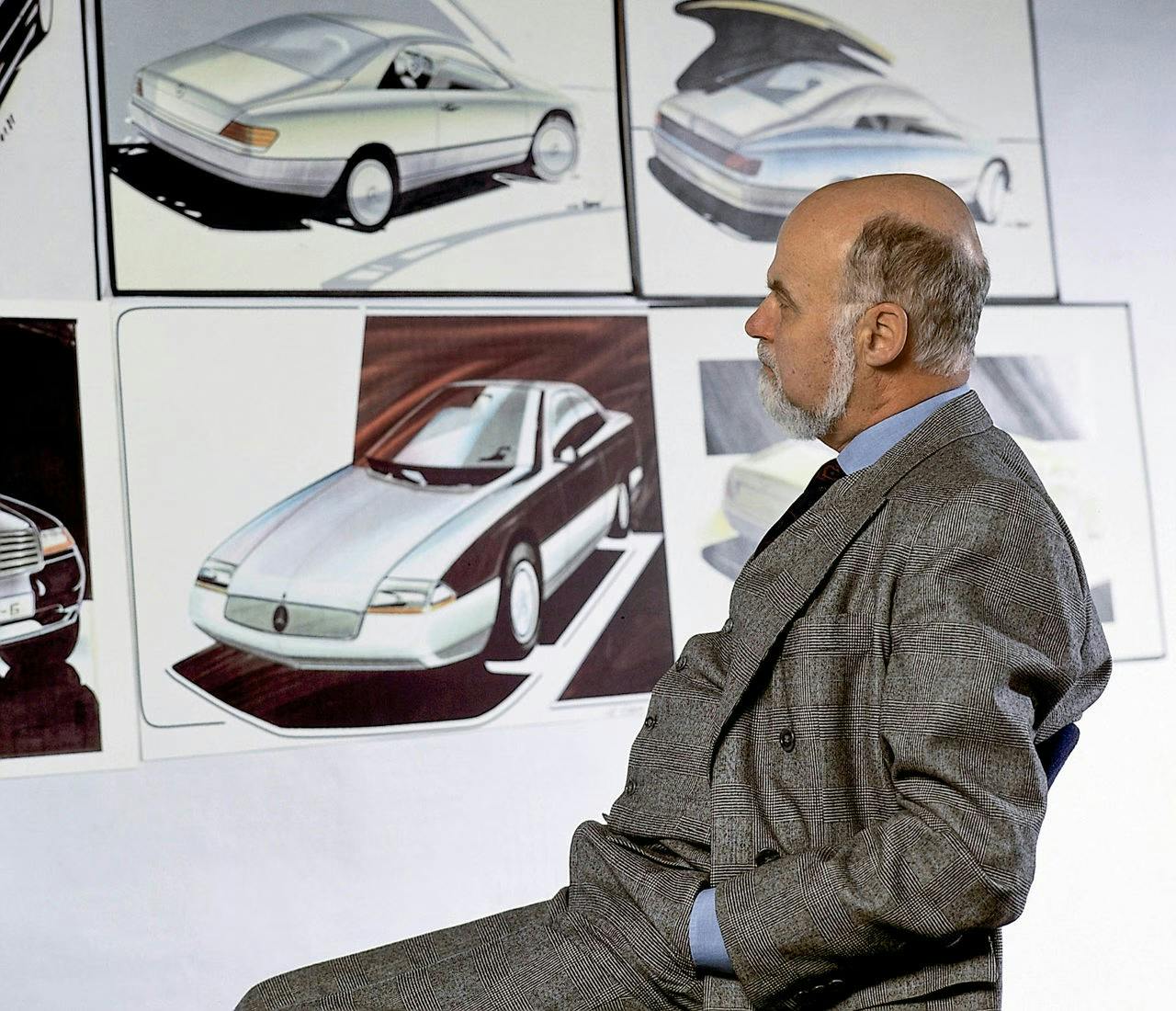

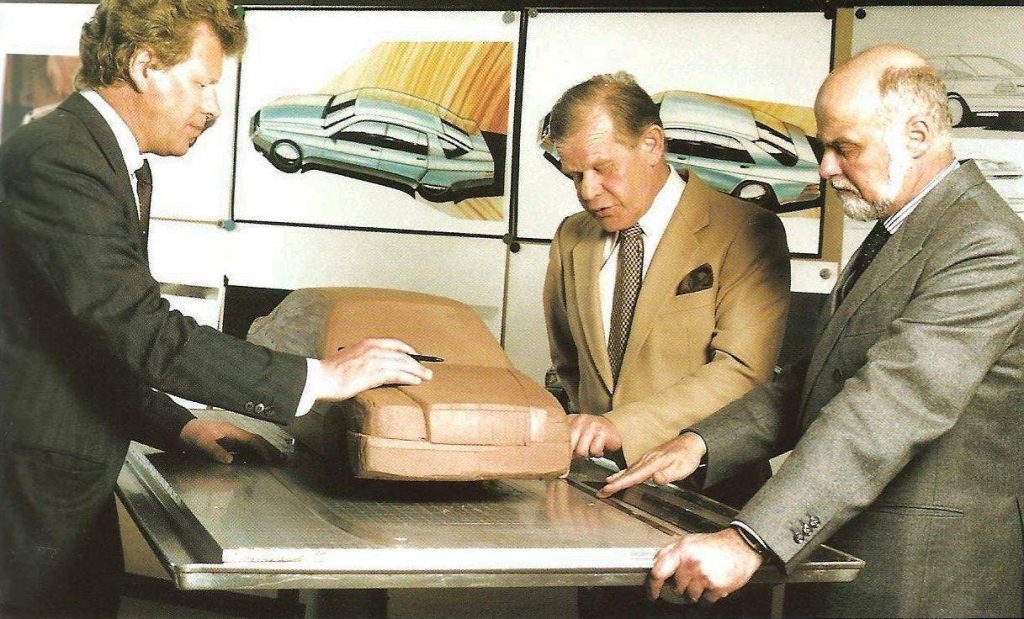

The words “Sacco’s team” are critical here. As design director, Bruno Sacco didn’t physically draw anything but was more of an orchestra conductor, leading a vast group of creatives working together to produce a harmonious result. The fact that the vehicles designed under his watch remain so closely associated with his name is a byproduct of the precise, painstaking development process in the Sindelfingen studio.

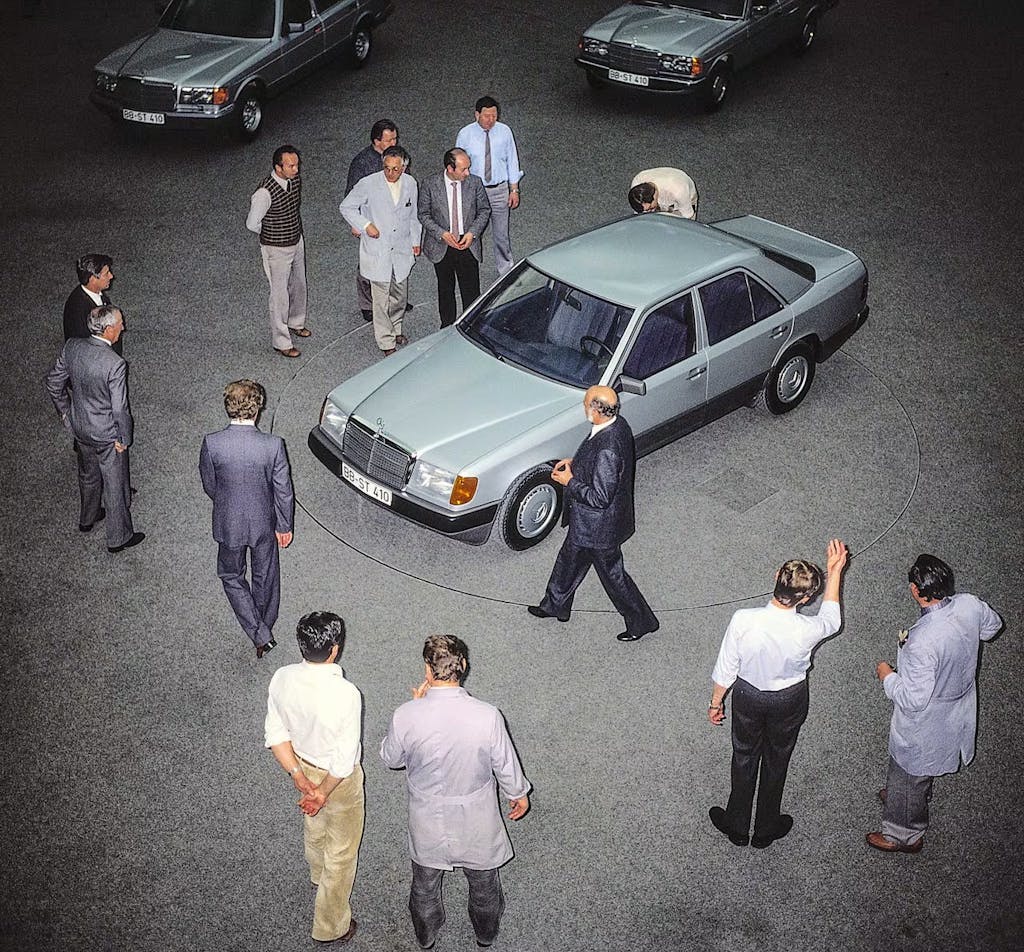

Mercedes-Benz’s vast resources and the long life cycle of its models meant the design team had the time to explore all possible directions, which were then carefully weeded out and honed to perfection via painstaking work through innumerable clay mock-ups. And that attention to detail in the clay modelling phase played a crucial role in how Mercedes-Benz vehicles exuded a unique air of quality.

Even in those years of “folded paper” automobile design, Mercedes-Benz consistently retained a somewhat softer look, and that was no accident. The relatively large radiuses and well-judged crowning of the surfaces were there to give the impression of a thick, strong metal, of a shape cast in one solid piece rather than stamped sheet metal. Each team member’s contribution ended up naturally diluted by the protracted, iterative nature of this process, so to this day, no single designer can “claim” the W126 or any other Mercedes model from the era as their own.

The W126 S-Class was a massive step forward from the W116 it replaced, yet it retained enough familiar design elements to be instantly recognisable as an S-Class. That, of course, was part of a deliberate strategy called “Vertical Affinity.” In Bruno Sacco’s view, a Mercedes-Benz must be recognisable as such in 10, 20, or even 50 years. This was achieved by deliberately retaining and evolving essential design elements through the various model generations.

But if Mercedes engineers and designers had to strike a seemingly impossible balance between opposing requirements with the W126, things were even more challenging at the opposite end of the company’s lineup. That’s because the “Baby Benz,” as the W201 sedan was called by the press, was completely uncharted territory for the marque.

Launched as the 190 in 1982, the W201 was Mercedes-Benz’s first compact sedan. As the model had no precedent in the marque’s lineup, the design team’s objective was to ensure the 190 looked like a member of the Mercedes family but without making it a scaled-down copy of the larger models. That “Horizontal Homogeneity” was the other key pillar of Bruno Sacco’s tenure as Mercedes-Benz’s design director: Each model in the marque’s model range must be instantly recognisable as a Mercedes-Benz through a common design language.

The W201 was an overall less formal, more resolutely contemporary design than the W126. Brightwork had vanished, except for the traditional front grille, raked back for aerodynamic efficiency. The wind tunnel also dictated the 190’s more pronounced wedge shape, with a tall rear end whose visual weight was cleverly leavened by the chamfered planes on each side of the deck lid.

The 190’s stark modernity surprised many and divided opinions at launch. But if it doesn’t look like much to you today, it’s simply because of the hundreds of imitators that followed over the years. Bruno Sacco’s string of successes at the helm of Mercedes-Benz design then went on with the mid-size W124 sedan and culminated with the R129-generation SL.

Yet, right as the all-new SL was being launched to worldwide acclaim, Sacco was perilously close to losing his job.

That dramatic inflection point in Sacco’s career came with the W140 S-Class project. During the long gestation of the new flagship, Mercedes-Benz’s dominance of the luxury sedan segment came under attack from BMW and its very accomplished E32 7 Series. Determined to muscle those Bavarian upstarts off the road, Mercedes threw everything at the new S-Class. A byproduct of this approach was that the car’s dimensions ballooned during development, spoiling its proportions. This set Sacco and the company’s management on a collision course, and after he was eventually overruled, the clash weakened his position within the company.

Launched right into an economic recession, the W140’s portly size and sheer engineering hubris felt out of step with the times and was almost universally panned in its native Germany. As a result, the W140 S-Class sold well below expectations and would be the last cost-no-object programme at Mercedes-Benz. After that, management embarked on a cost-cutting spree to boost margins as the company’s cash reserves were used to fund several high-profile acquisitions.

It didn’t take long before standards began to slip in Mercedes-Benz’s design department, too, as Bruno Sacco’s thoughtful “Vertical Affinity/Horizontal Homogeneity” approach gave way to “Design Freedom.” Design integrity and sobriety were out, substituted by an increasingly desperate chase of the latest trends that, together with well-publicised reliability issues, took a lot of shine off the three-pointed star.

Bruno Sacco retired from Mercedes-Benz in 1999, but his mark on the carmaker’s history remains one his successors can only dream of. Thanks to their impeccable design integrity, the Mercedes-Benz models developed under his watch have aged like the finest of wines, and all are now being increasingly appreciated by a new generation of enthusiasts.