Robert Gunn’s astonishing models of celebrated off-road vehicles have me absolutely spellbound, but after a few hours in his company I’ve come to realise there are two secrets intrinsic to them all.

One is what Gunn calls his favourite tool, a digital vernier gauge that’s always in his pocket and helps him to stick rigorously to scale. The other is something much less tangible. It’s his quirky imagination. Gunn sees parts of classic 4x4s everywhere he looks – from a discarded pen to the crowded shelves of his local pharmacy.

Take, for just one example, the steering wheel of his Hotchkiss Willys Jeep. Its rim is a section of thin copper tube bent into a perfect circle and then painted. The spokes are industrial sewing pins drilled through at precisely the right points, and the hub is the end of a pen cap. It’s all held perfectly in place with thin-grade superglue and took four hours to make. The effect is fantastic, yet Gunn is his own harshest critic.

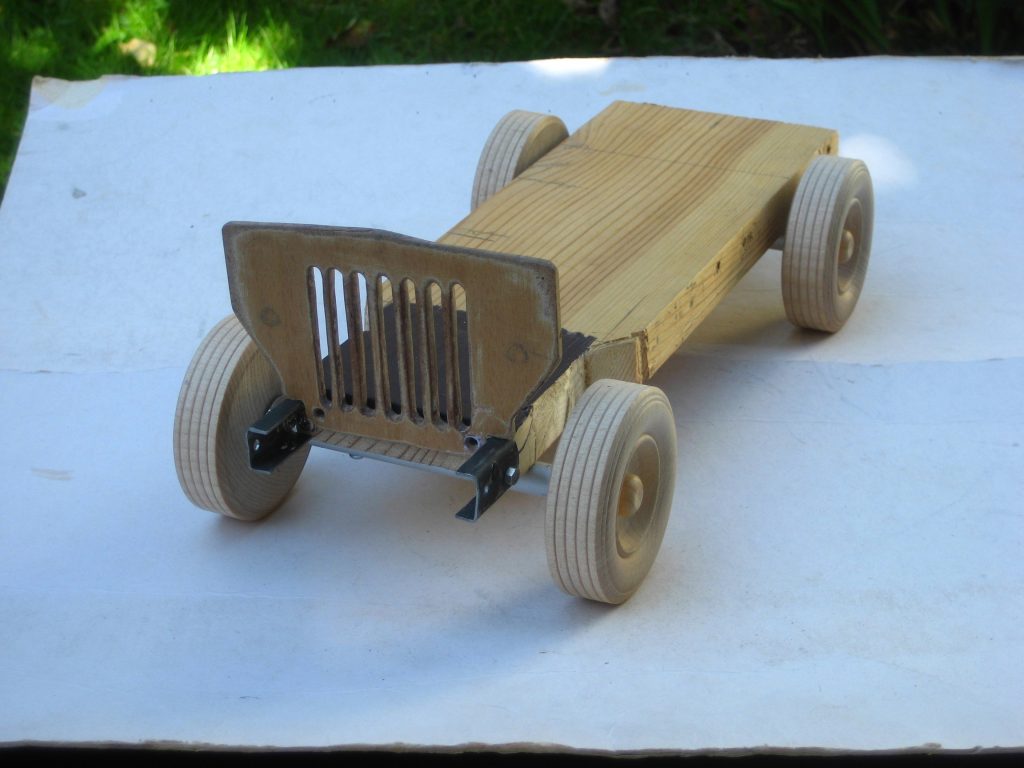

“Hmm, well, I now find some of the detailing a bit crude, but I was on a learning curve with my first one,” he says. “The process for the Hotchkiss became the process for all the others, although on this first one I discovered I needed to give the wooden structure a drop-down chassis, or else it’s too compromised.

“And wheels… I’ve found wheels are one of the hardest parts of all, and you’ve got to have them sorted out first, because they’re the determinant hardpoint. I can’t make wheels as I don’t have a lathe and I don’t do any welding or soldering. My workshop is 6x4ft, about as big as a sofa, so everything has to be very simple to cope with.”

The wheels on the Hotchkiss are wooden, bought online and brought to life by Gunn with the addition of rubber covers from landing wheels of a radio-control model aircraft. Later, as he moved on to tackle an early Datsun Patrol and Toyota Land Cruiser, he found the wheels from a Toys R Us plastic howitzer gun were absolutely ideal.

A bit of background… Robert Gunn is a retired surveyor and loss adjuster in the UK who’s developed a unique set of model-making skills over the last 10 years. They didn’t come totally out of the blue, mind. His father was an art teacher and lecturer in pottery, and the family home was constantly full of tabletop works-in-progress. “I enjoyed metalwork and woodwork at school, but my father could really make things by hand quickly – he could make a three-dimensional model of a cat in soft clay just by looking at it.”

As a considerable petrolhead, Gunn’s early passion was classic US pickup trucks, and over the years he accumulated a huge collection of model Dodges, Fords, and Chevys in a variety of scales, and he was drawn to anything that reflected cargo-carrying Americana. The French-made Toyota Land Cruiser plastic toy he found at a Kent military vehicle show for a mere 75p in 2007 was at the fringes of this miniature universe. But it had certain qualities.

“It was very, very basic, made by Joustra as a cheap kids’ toy in the 1970s, but the proportions are excellent. All the vents and shut-lines are correct. I realised it had possibilities, and I started to detail it as best I could. I added a front bumper made from hardwood. I made some headlamps from magnifier lenses with silver foil behind them, and I used orange Perspex for the indicators. The Toyota badge was cut out of a magazine. The windows I glazed with sheet plastic.”

The result was utterly transformational. It was now showpiece. And Gunn found its unusual scale of 1:10 was perfect for crafting his additions. “It’s just so simple for converting metric measurements to Imperial ones to achieve accuracy,” he explains. “One inch is almost exactly 25mm.”

All of this knowledge led him to build his first vehicle, the Hotchkiss Jeep, from absolute scratch in 2012–13, forming the basic shapes in wood and ingeniously adding everything else by scavenging odds and ends that everyone typically tosses in the bin. He went much further than a simple representation. The Jeep has an opening bonnet shaped from nickel-silver, under which is a super-accurate model of its distinctive Hotchkiss engine, down to its plug-leads and carburettor. He lavished 375 hours in total on the car, including those four on the steering wheel.

“It completely stretched me out of my comfort zone, because I had to come up with all the techniques. But what I really learned was how to keep a mental picture of what the model will look like the whole time I’m working on it.”

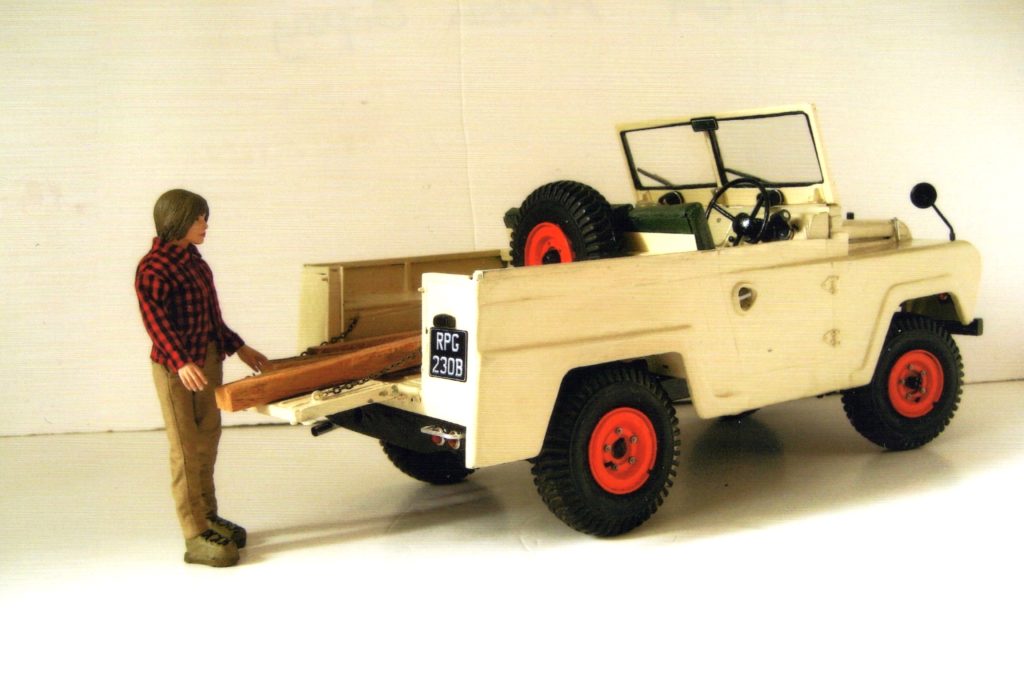

Gunn explored the entire canon of early sport-utility vehicle history for each year’s project, tackling the Patrol and Land Cruiser, a Suzuki LJ, a Land Rover Series I 107 pickup, an Austin Gipsy, and the very final Land Rover Defender. The average time spent on each one is 400 hours, during which he’ll painstakingly fashion around 1000 separate parts.

Often, accurate reference data is all but impossible find. He’s never actually seen the real-size Datsun Patrol, for example, absorbing its character from three US-market brochures, and there’s never been a reference book on the obscure Austin Gipsy – even line drawings in contemporary road tests proved unhelpful in getting the proportions right. As I am the first person to interview Gunn about his work, and as we discuss his models, it seems achieving the three-dimensional relationship between the wings and bonnet on a vehicle is the toughest part. “It is a huge challenge, the body shape. I have nothing in front of me so ultimately, it’s going to be my impression of what it looks like. Exactly how high is the wing above the chassis, for example? On my Suzuki, I now think the front overhang is very slightly too long, but after all the time building the working suspension and steering I can’t face starting again! And it’s all by eye and not using any computer data feeding into a 3D printer. Something circular with a scale-able diameter obviously means I can get going with it to make a small component.”

And here, to me, lies the magic allure of Gunn’s craft. Take wing mirrors. On the Datsun they’re cut-down dental mirrors with their stems bent at the right point. On the Land Rover Series I, meanwhile, they’re buttons on Gunn’s hand-made brass stems, with silver foil lenses.

For the Land Rover Defender’s doors, tiny Phillips screws from a dismantled camera form the crosshead bolts on the hinges. The hubcaps on the Land Cruiser are cut-down lids from roll-on deodorant bottles that Robert spotted in a Boots pharmacy. “Exactly the right dome profile and matte silver colour, and even a bit of tarnishing after years on display is actually fine,” he grins.

Back to that 107 Landie. The galvanized plates at the edge of its panels use real zinc squares from Chinese lab suppliers, carefully scissor-cut to shape. Its ribbed headlamp lenses are from a broken Bratz doll’s Cadillac toy car, bought for a fiver at a country fair, while the chrome surrounds are women’s-size stainless steel rings sliced in half; they were so hard to cut with a hacksaw that Gunn gave himself a repetitive strain injury, and if he ever does them again he’ll start with solid silver, which is much softer.

On the Defender (build time: 547 hours), the wonderfully accurate canvas canopy is actually some offcut beige cloth that, once sprayed with varnish, gave the correct tan colour and authentic ‘draped’ stiffness.

Gunn went somewhat left-field for his 1:10 model of a 1950s Standard Eight pick-up, choosing his subject simply because he liked the original. He achieved the curvaceous styling from several layers of plywood that he sculpted and filled – unlike a typical off-roader, there’s not a flat panel on it – and the experience was, he says, pretty gruelling. You can sense the relief when it came to improvising the small parts, such as dental floss nylon brushes for the wishbones in the working front suspension; part of a pump-action handwash dispenser for the exhaust silencer; and a pill bottle covered in ribbed plastic sheet as a petrol tank. Awesome stuff in hundreds of tiny ways.

Gunn likes his finished work to be showcased in a diorama. He picked a marine theme for the Land Rover 107, spending hours online until he found a resin fisherman figure at the right scale that he could customise until the shine on the boots and oilskins was to his liking. Until now she could never know this, but actress Jennifer Lawrence – she of The Hunger Games – has helped Gunn out here often. His relentless research turned up a 1:10 scale merchandise model of her, fully pose-able, that fits a treat with his cars. Especially after he’s designed and made an outfit appropriate for, say, loading sacks through one of his opening (with a tiny, hand-made bracket) tailgates…

Robert Gunn’s models are not for sale, nor have they ever been displayed publicly. “They’re my pride and joy,” he says. “I love making them.” But he does add, warily: “You will tell your readers that I don’t do commissions, won’t you? It would have to be a polite ‘no’, because each one can take up to 500 hours, and I just don’t want it to feel like work!”

What a Fabulous read I had this morning you could pass this guy in a street or a Shop & you wouldn’t realise that is passion for his hobby & attention to detail is unbelievable & he is right to say he doesn’t want every Tom Dick or Harry pestering him to build a Model for them it’s not money or people that drive this guy It’s his pleasure of scouring the bits from all walks of life it’s that when he wakes in a morning has breakfast read the paper a leisurely walk to the Shed with a brew maybe a Radio on softly & he’s quite happy with life & let’s hope he makes more models for us to enjoy through obviously.