Editor’s note: Hagerty US Media’s editor-at-large, Sam Smith, is a lifelong student of automotive history, who drinks a lot of coffee. After he started sharing a photograph and potted history with the Hagerty Media team, we thought it was worth showing it to you, too. Enjoy.

Let it be known here and now that your narrator is a sucker for a great many things.

One of those things is the Rolls-Royce PV-XII Merlin.

Some of you may be nodding. (Greetings, fellow nerds!) The rest are probably thinking, “Rolls… wizard name… which car was that? Some big prewar moose with running boards?”

Well, big and prewar, yes.

Not a car, though.

So very much not.

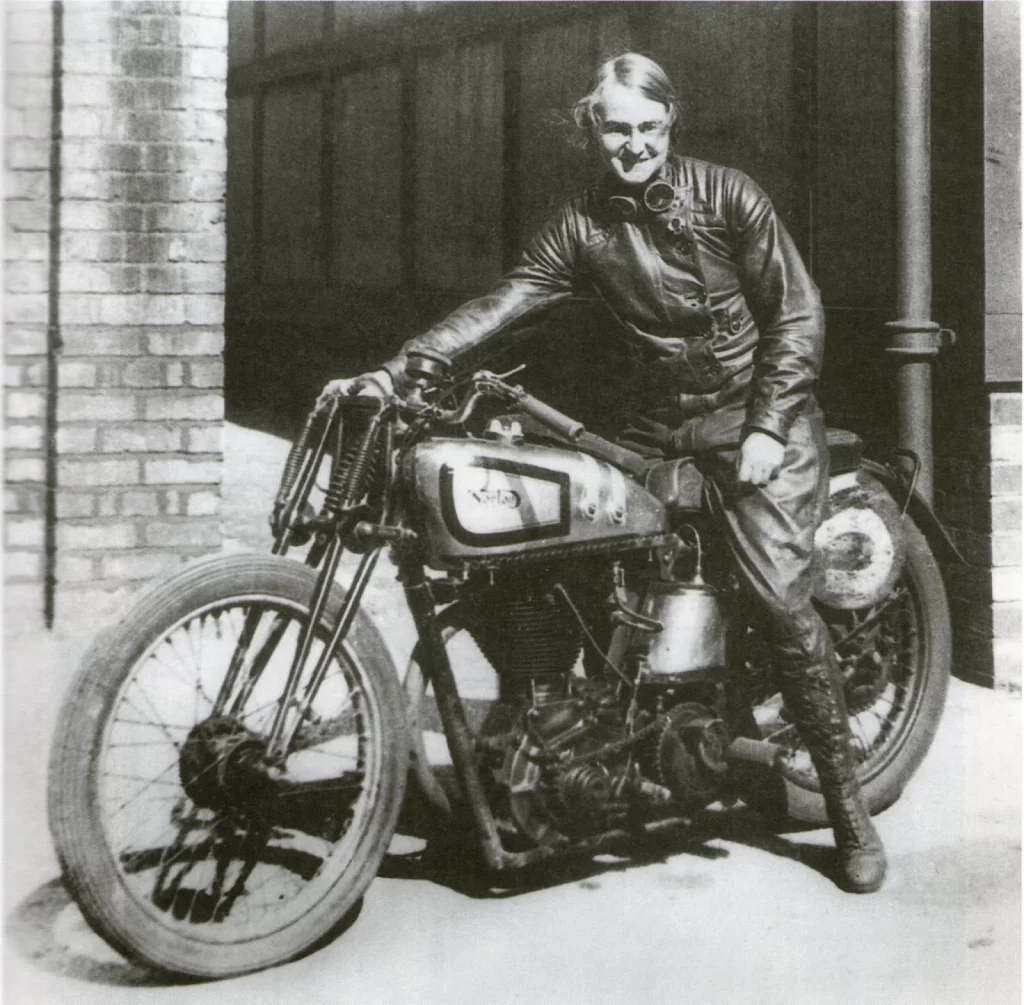

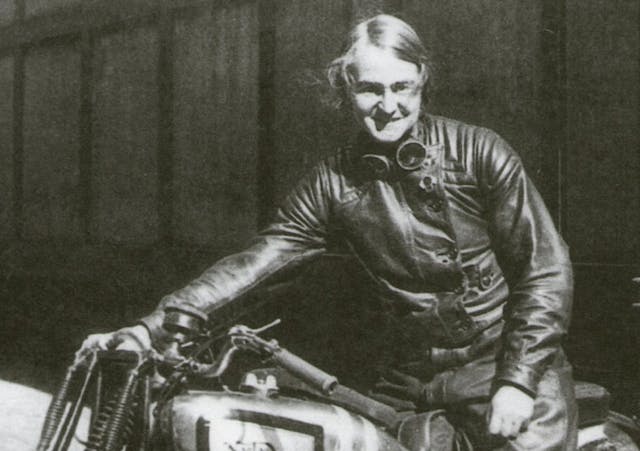

The Merlin’s story also involves a lady named Beatrice Shilling. Her tale is famous and so may ring familiar. We’ll get to that. For now, let’s just say hi to a smiling person on a motorcycle.

The Merlin was an aircraft engine used in World War II. It was installed in several types of airplane, notably the North American P-51 Mustang.

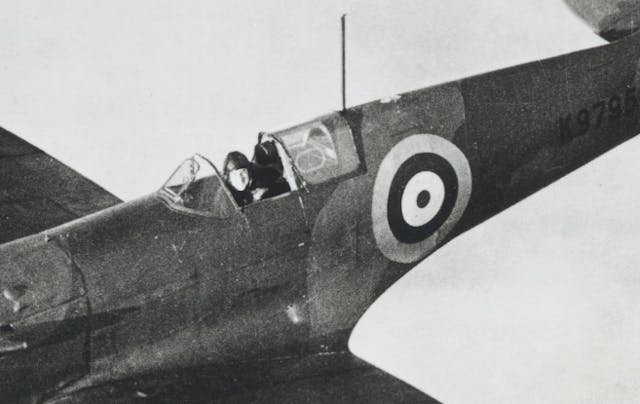

Another airplane made it famous, though. This:

Witness the Vickers-Supermarine Mk1 Spitfire. More specifically, witness airframe #K9795, the ninth Mk1 built, photographed for a British newspaper in 1939. Because the internet is a delightful place, the early history of that specific airplane can be perused here. (Note the forced landing after engine failure, October 1940. Spits stalled at remarkably low speed – just 65 knots – and yet the idea of dead-sticking one home can prompt personal… clenching.)

Like all Spitfires, K9795 made wonderful Doppler noises at speed. A Merlin tossed into a hard bank directly over your head is one of the most gut-stirring sounds in the entire blessed history of the internal-combustion engine. There are many, many reasons for this, not least of which are the nature of how sound travels among air molecules and the emotional power of an elegant object in flight.

Mostly, however, the thing just crackles and popples and does this neat little childhood-airplane-cartoon-noise trick in a way that makes your toes go fizzy.

Digression: Take a moment to watch this. That link leads to a YouTube clip of British pilot Ray Hanna giving Alain de Cadenet a haircut. Imagine the audio at deafening volume. Better yet, find a set of headphones and play that clip at deafening volume.

Digression again: Hanna, an absolute unit, once flew a Spitfire down the front straight at Goodwood. As in, over the pavement, between occupied grandstands, flagpole height. There is video. The act was lightly illegal and quite dangerous, and he was summarily reprimanded. Because England is England, however, the flight also minted him as a kind of folk hero. Bless that nutty land forever.

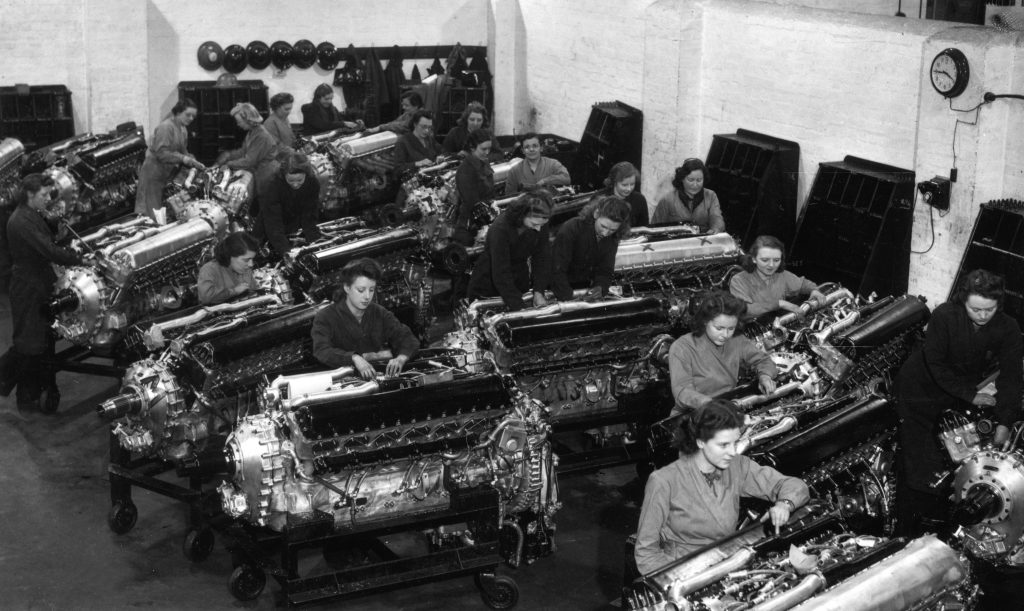

Check that top shot again. It came from the Getty Images wire archive; the shutter clicked open on 2 March, 1942. The location, the caption says, is a Rolls-Royce Merlin factory “in the northwest of England.” The wall clock reads 3:45.

Witness the employees. They are cleaning a flock of freshly built Merlins. A small engine, by aviation standards. Those ladies are not Oompa-Loompas, and yet, they look small.

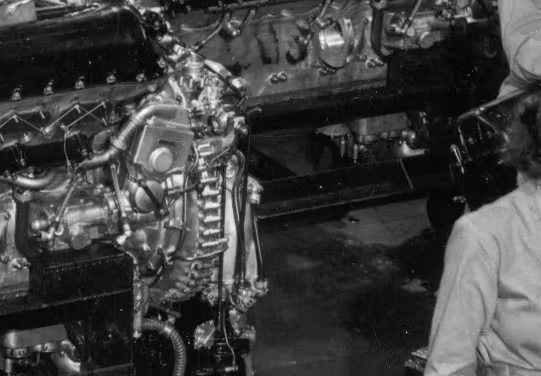

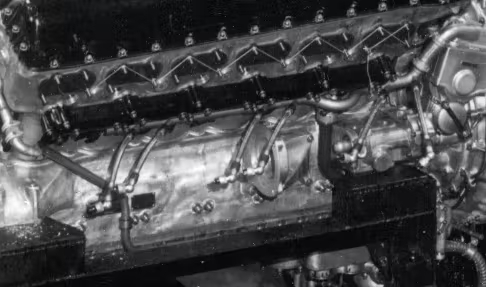

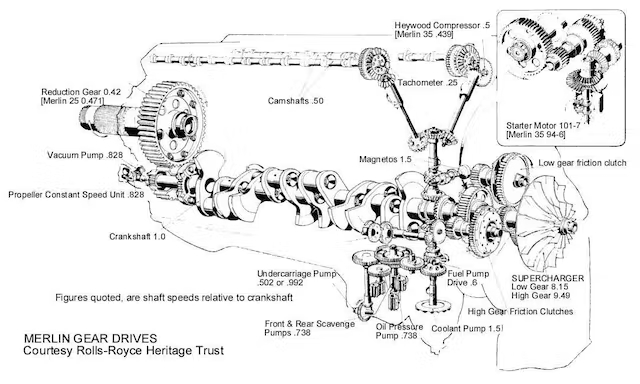

Some Merlin facts are obvious. This is a vee design: two banks of cylinders angled outward over a central crankcase. The inside of the vee is home to various plumbing and ignition bits. If you understand how engines work, you may notice something like a crankshaft nose poking out at left. If you are really up on your Old-World Machines of High Specific Output, you will perhaps recognise that each Merlin wears a centrifugal supercharger at the rear.

Digression again again: centrifugal superchargers still exist. Most now resemble a dumbed-down turbocharger, small and dense. Imagine a ceiling fan where the blades are squished short and at steeper pitch. Now picture that fan inside a disc-shaped metal housing.

The “fan” turns, driven by the engine. The engine breathes through that fan housing. Air goes in one end, is squished and compressed by those blades. Newly pressurised and thus more dense, this air is then shoved out of the housing and down the engine’s throat.

Internal-combustion engines burn a mix of air and fuel at specific ratio. This process hinges on and is made possible by oxygen content. When air is more dense, it contains more oxygen. Sticking to the ratio thus means adding and burning more fuel. All else being equal, that means more power.

That forced compression is especially useful in an aircraft at altitude, where air is thin to begin with.

In Spitfire trim, a Merlin displaced 27 litres. One thousand, six hundred and fifty cubic inches. Each cylinder was 5.4 inches in bore. Piston stroke was six inches. Each cylinder bank wore one cam, and those cams were driven by an arrangement of gears and shafts in the block.

By the admittedly absurd standards of aviation engines, the Merlin was a middleweight. Nonetheless, some bits of trivia give pause.

Bit One: See those six exhaust ports? Where the wire runs between studs in a triangular pattern? In flight, exhaust gas exited those ports at around 1300 mph.

Bit Two: In a Spitfire, the Merlin’s exhaust vented out the nose cowl. Its stacks, or ejector pipes, simply poked into the slipstream. Early on, engineers observed that aiming those stacks aft gave a noticeable increase in the airplane’s top speed. At 300 mph, the thrust gain mirrored what the engine would have produced if given another 70 horses.

Bit Three: If Wikipedia is to be trusted, a Merlin run at full power will in one minute inhale enough air to fill a city bus.

And so the supercharger feeding all that was not small.

What, you ask, was “full power”? Output varied with boost pressure, fuel quality, and altitude. The design entered production in 1936. Max chooch, as the internet says, was then around 1000 hp at 3000 rpm.

This rating is what combat aviation calls “war-emergency power.” A Merlin at full snort subjects itself to great stress, and pilots were advised to operate the engine in this fashion only for short periods. Moreover, regulations required that event to be logged with the plane’s ground crew. The crew’s reaction varied with operating time and load – imminent maintenance for the engine at best, full teardown at worst.

As a child of wartime, the Merlin was rapidly improved. Design and fuel changes over time allowed maximum boost to rise. When the engine was born, that supercharger was limited to just 6psi of boost. By war’s end, it was allowed to give more than 20. By 1950, the final year of Merlin production, that 1000-horse rating had basically doubled.

She was a churner, this marvellous device, but also light and durable. And because the fine lads at Rolls chose to over-engineer certain bits, she just kept taking more.

Digression the second: that crankshaft-looking thing at the front is the propeller shaft. The big bulge behind houses the prop’s reduction drive. This assembly was basically just a pair of gears, one large and one small. That disparity in gear size allowed the Spit’s three-bladed prop to run at just under half engine speed.

Twenty-seven litres. A Mazda MX-5 displaces just two. And yet a Merlin is so much more than thirteen and a half Miatas.

Imagine the climb torque, the descending turns, the balletic motion a Spit can produce.

How odd, that so much of what we build for war can so often move with such immense beauty. Still, that’s people, I suppose. We are none of us simple and one-sided.

And so we return to Miss Beatrice Shilling.

Her nickname was “Tilly.” In the 1930s, she raced motorcycles. She lapped England’s enormous Brooklands oval at more than 100 mph, one of just three women to do so. [Read about the battle to be Brooklands Speed Queen, here. Ed.] After the war, she raced cars at Goodwood. In the late 1960s, American Formula 1 and sports-car legend Dan Gurney brought her to his shop to consult on F1 cooling problems. In spite of all that, she is known primarily for what she did to the Merlin. The change she made that helped win the war.

Here’s the thing: I have failed this woman. I intended to sit down this morning and share Miss Shilling’s story here. It’s really quite lovely. Instead, I grew distracted while relating the goony details of the engine on which she worked. I ran out of space.

And really, how can you not get distracted by a Merlin?

Given what I have read of the woman, this is probably as she would have liked. Nonetheless, she deserves more. Do me a favour: Read this version of her story, when you have a moment.

Bookmark that link, email it to yourself, whatever. Read it if you want to know how a lovely individual made a lovely and important engine even more lovely and important. Hell, read even if you don’t. Perhaps you are merely curious as to why one should never, ever put an unmodified early Supermarine Spitfire into a negative-g manoeuvre when the fuel-injected Germans are coming at you out of the sun.

I mean, aren’t we all curious about that?

Read more

How engineer Beatrice Shilling saved the Spitfire

The epic battle to be Brooklands Speed Queen

British artist wants to build a Spitfire-powered racer