Most car enthusiasts can tell you the moment they first fell in love with the marque or model they have the most passion for. Perhaps it was a clapped-out Mustang that meant teenage freedom. Maybe it was the Westfalia from family camping trips. Possibly it was seeing a DeLorean DMC-12 time machine scorch up a parking lot while you munched on popcorn at the movie theatre. However, for those of us of a certain age, all we really wanted was a pickle car.

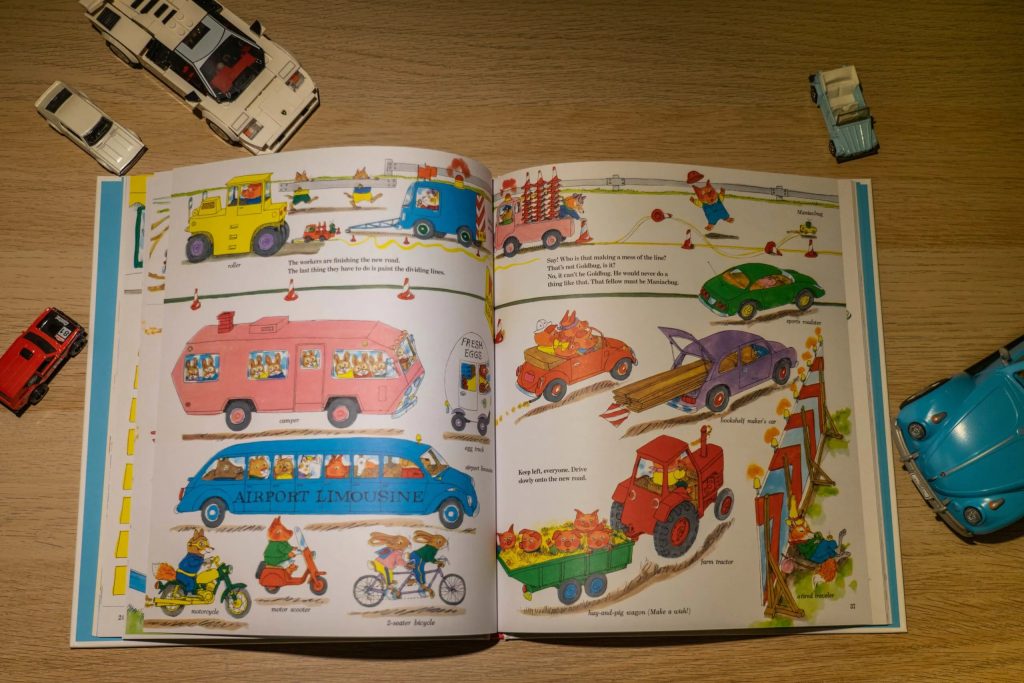

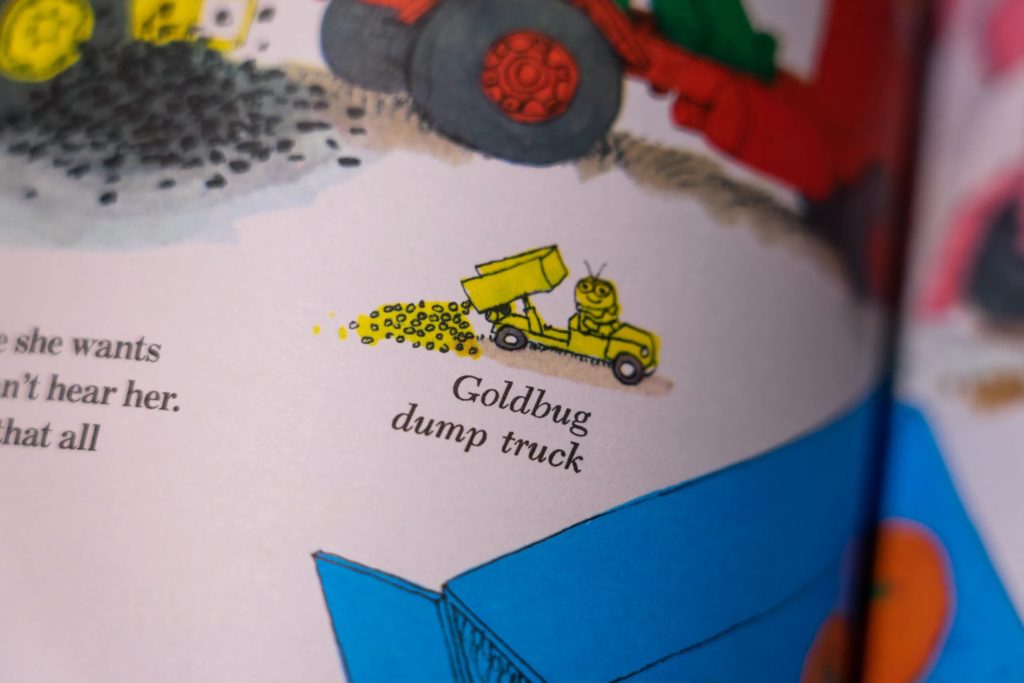

Or a carrot car. Or a bananamobile with seating for three. Or a wedge-shaped cheese car for all our mousy friends. In the fictional world of Busytown, the roads were simply crammed with all manner of magical wheeled delights, the kind to mesmerise both parent and child at bedtime. Where’s Goldbug? There he is!

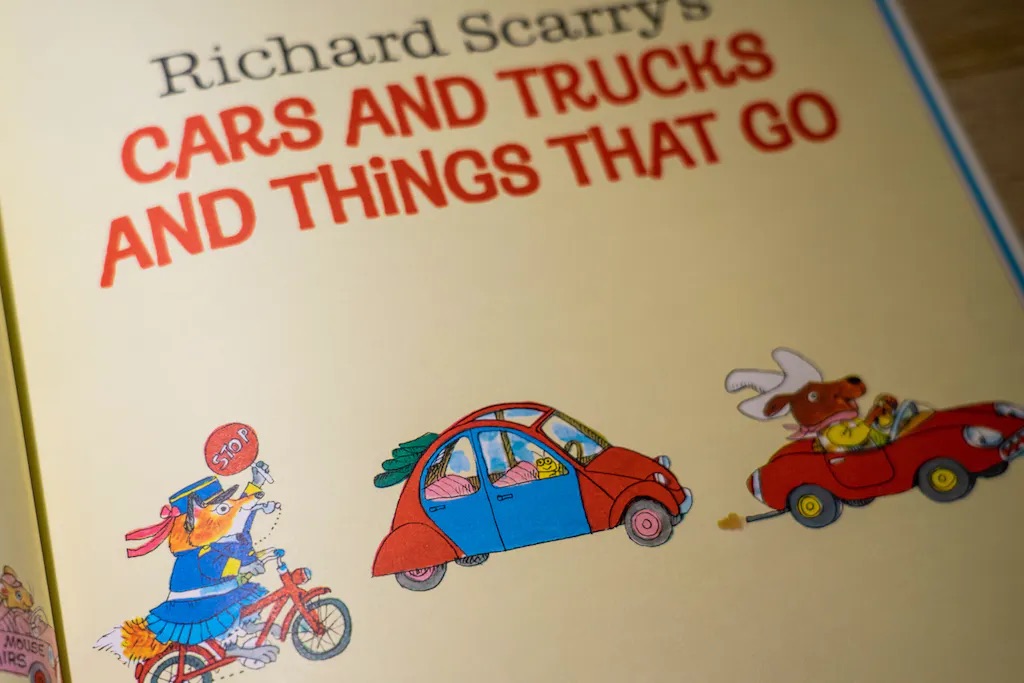

Fifty years have passed since children’s illustrator Richard Scarry created his beloved Cars and Trucks and Things That Go, and it still carries that magical first spark of automotive enthusiasm.

Well, of course it does. Because Richard Scarry was a true car guy from the very beginning.

Born in 1919 in Boston, Scarry was the second of five children, and his parents were relatively well off, with a family-owned chain of department stores. “Scarry,” by the by, is an Irish surname, and should properly be pronounced to rhyme with “marry.” But we all knew him as Richard “Scary.”

As a young man, Scarry did not inherit the family zeal – or the aptitude – for business. He dropped out of business school in Boston, then enrolled in art school, before being drafted in 1942 to fight in the European and North African theatre of WWII.

His service life began with radio repair and ended in the morale division, where he was employed as an illustrator, editor, and writer. Postwar, he carried this work into the magazine and book publishing world, while living in New York. At the tail end of the 1940s he met and married Patsy Murphy, also an illustrator, and the next year Scarry got his breakthrough illustrating the Little Golden Book series. Obviously feeling optimistic about the future, he treated himself to a sports car.

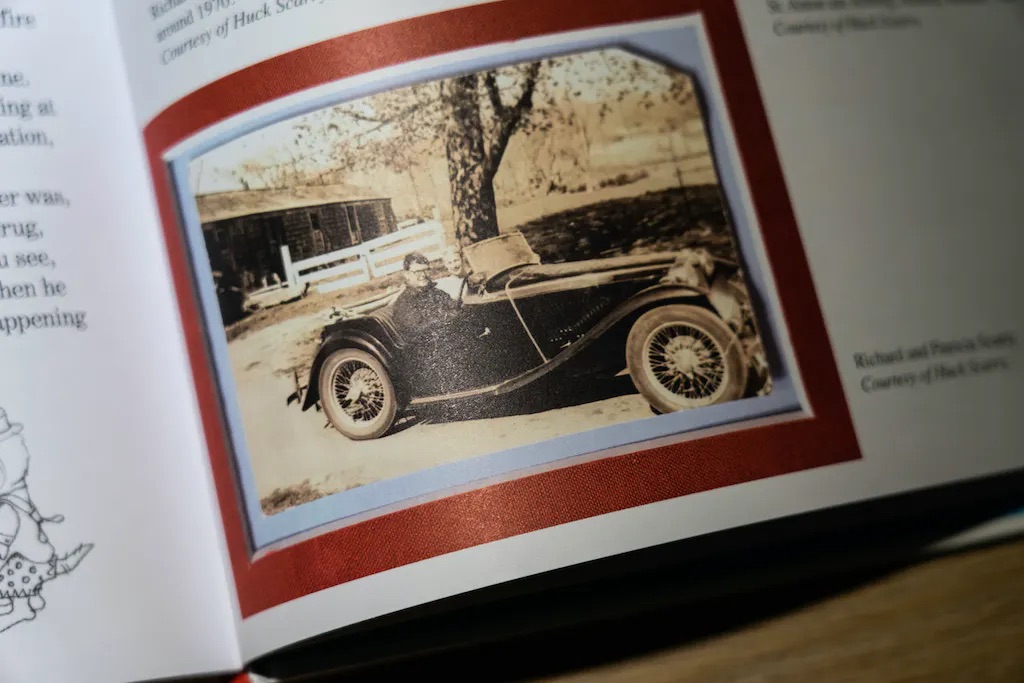

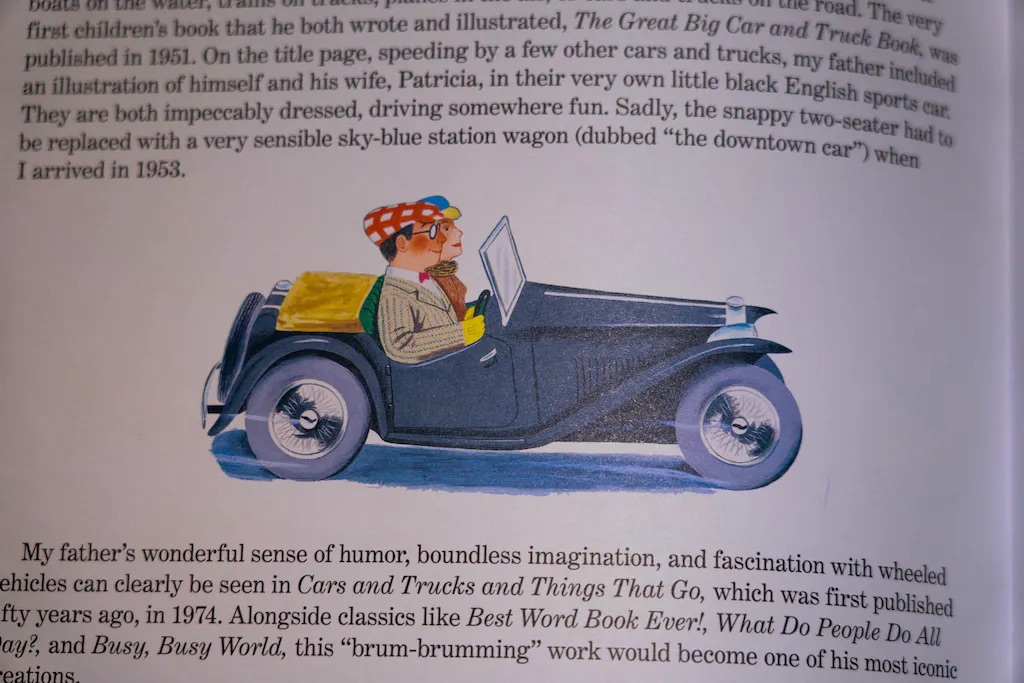

Specifically, it was a black MG TC, one that Scarry’s only son, Huck, describes as a “snappy two-seater.” The postwar sports car boom in the U.S. is well documented, and Scarry is not the only ex-serviceman who found himself charmed by an MG’s fizzy exhaust and scrappy handling. And besides, is anyone surprised that Richard Scarry owned an early, friendly-faced MG? The car looks like he was the one who actually designed it.

Sadly, the MG left the Scarry garage after Huck was born in 1953, replaced by a sensible station wagon of some kind. However, Scarry made sure to immortalise the little English car with an illustration on the inside cover of 1951’s The Great Big Car and Truck Book, the first work he both wrote and illustrated.

By this time, Scarry was working with his longtime publisher, a Dane by the name of Ole Risom. Risom had one of those lives that sounds impossible to believe, escaping Europe in 1940, joining the U.S Army ski patrol in WWII, then getting hired on with the Art and Monuments section (the subject of 2014’s The Monuments Men movie), and marrying an actual countess. The pair would be close friends and collaborators for decades.

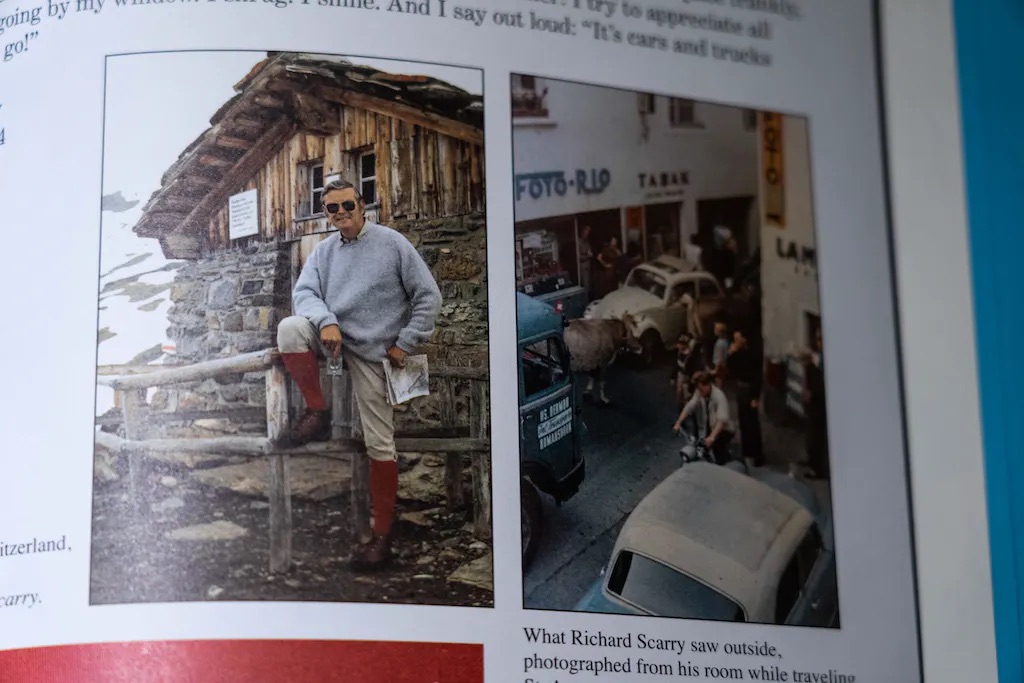

In 1963, the Scarry family visited Europe, and it changed everything. Looking out on a crowded, bustling street, Scarry was inspired with the concept for his Busytown series of books, and with that year’s Best Word Book Ever, he cemented his signature look.

Part of that look was inserting his family into his books. Huckle Cat is based on Huck Scarry, and he wears traditional lederhosen because the Scarrys lived in Switzerland in 1968, and later bought a chalet in Gstaad, where Huck still lives today. And, in what sounds like a made-up detail, for that year abroad in 1968, the Scarrys lived in a town called Ouchy.

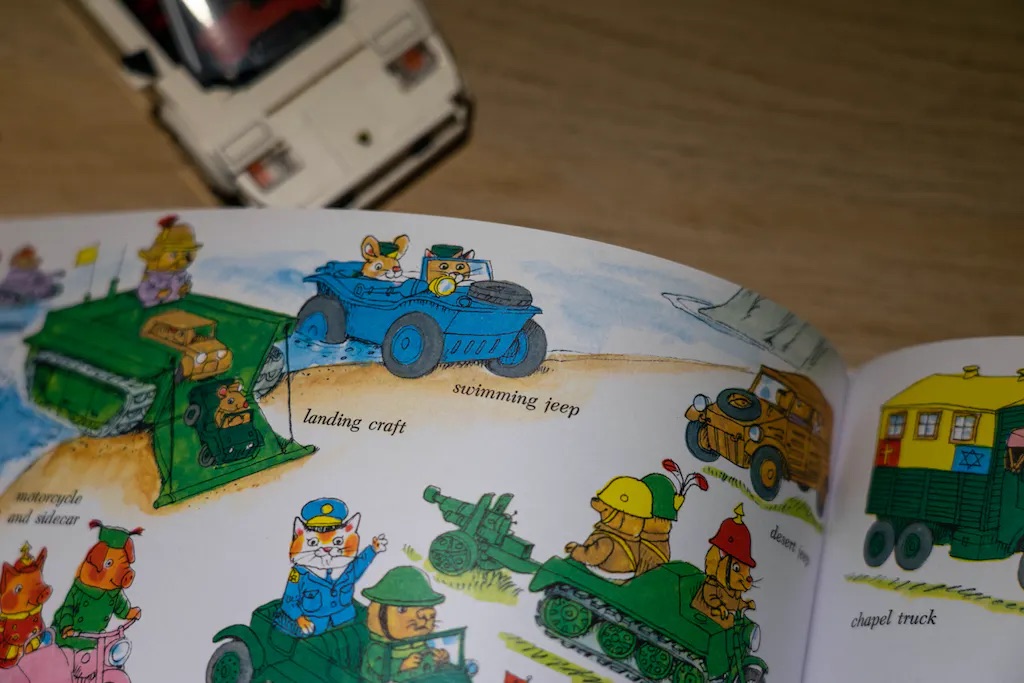

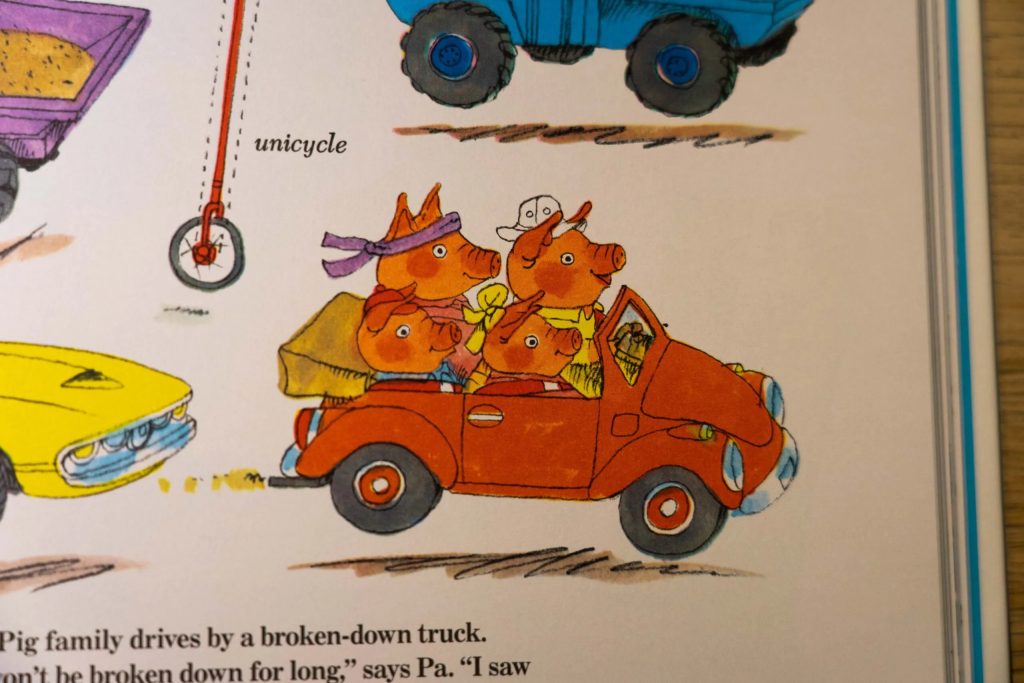

During this time, they owned what can be considered the hero car of Cars and Trucks and Things That Go: a convertible Volkswagen Beetle owned by the Pickles, a good-natured family of pigs. Scarry clearly was drawn to the anthropomorphic features of cheery classic VWs, and they often showed up in his work.

What has fascinated kids and adults for ages is the delicious details you find hidden in Scarry’s books. For instance, in 1968’s What Do People Do All Day, a cutaway illustration of a boat shows an accurate and detailed explanation of how a four-cycle piston engine works.

By the 1970s, Scarry had signed a new contract with Random House and had upgraded his European car from a Volkswagen to a black Mercedes-Benz W114 coupe. Despite splashing out, he remained fairly unpretentious about the car, never taking the snow tyres off of it, and occasionally strapping a boat to the roof.

Cars and Trucks and Things That Go was published in 1974. Huck Scarry was 21 at the time, and he assisted in colouring up the work. In the 50th anniversary edition, he talks about working with his father.

“Those days together in his studio were a real treat for me. While he painted, my father was always giggling or laughing at something he had drawn, no doubt remembering the situation, somewhere seen, that had inspired his illustration.”

Flipping through Cars and Trucks and Things That Go again, decades after I first read it or had it read to me, the book holds up like a great classic car. First of all, it’s huge, at nearly seventy pages long, and every one of them is crammed with jokes and details and treasure hunts. It’s basically a kid’s ideal “just one more book before lights out” stalling technique.

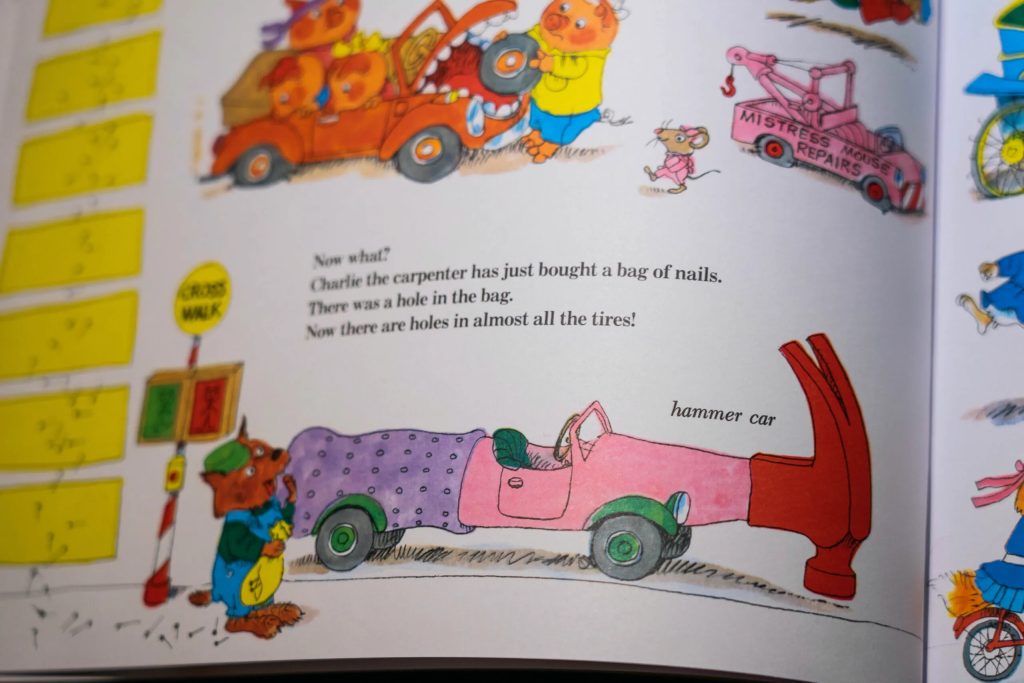

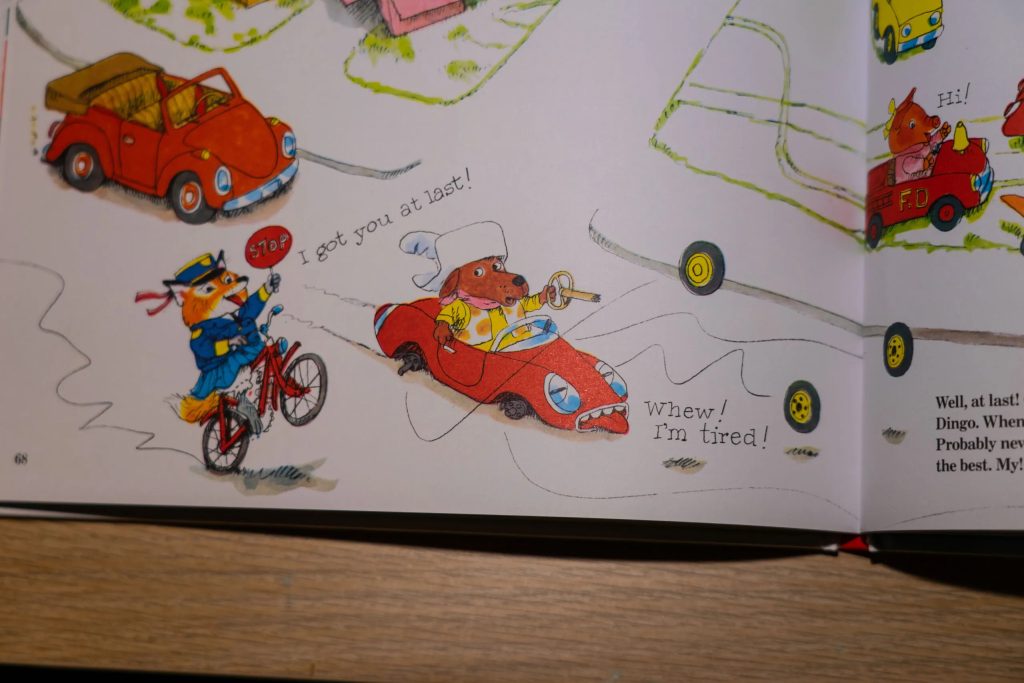

And as a grownup, it’s still brilliant. Here, Goldbug drives a Citroën 2CV. There, a cat and a rabbit hit the beaches in a VW Schwimmwagen. David Dog is behind the wheel of a Bond Bug. Rolls-Royces appear both in regular and fun-size. Careless Charlie the Carpenter sidles up to his Hammer Car – future inspiration for AMG? Four foxes ride in what is clearly a Pinzgauer. And of course Dingo Dog is scooting along in his toothy Maserati lookalike, with Officer Flossy in hot pursuit.

It’s hard not to compare Busytown’s colourful traffic with the reality of modern greyscale streets. We could use more happy-faced cars in a wider, brighter palette. I honestly believe it’d be an antidote to road rage if everyone drove around in cars that have the cheery mien of an MG Midget or a Honda e.

Richard Scarry died in 1994, at the age of 74, twenty years after Cars and Trucks and Things That Go had become an established household essential. He left this mortal realm in his beloved Swiss Alps. On one of his first trips there, in 1950, he’d bought a traditional Tyrolean hat called a gamsbart. He wore it constantly, but you may recognise it as the hat always worn by his character Lowly Worm, often at the wheel of an Apple Car.

At 50, Cars and Trucks and Things That Go has long provided the tinder that sparked the flame of automotive enthusiasm for many a young reader. The 50th Anniversary Edition includes additional artwork and a poster, and the best you could do is read it to your own kids or grandkids. Where’s Goldbug? There he is! Officer Flossy and Dingo Dog. Ma and Pa Pickle. Mistress Mouse, tow-truck driver and racer extraordinaire. And, of course, a pickle car, zipping down the road with a cheery pig at the wheel.

We all grew up to love real cars, and the true stories that went along with them. But given the choice, I know we’d all want to find out just how quick that bananamobile was when you floored the throttle. Surely we’d give Officer Flossy the slip.