A 62-year-old commercial builder in suburban Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA, Tom McGough is a discerning collector whose stable ranges from ultra-rare sports cars like a Ferrari 166 Inter, a Pegaso Z-103, and an ATS 2500 GT, to two dozen Willys hot rods. But his collection didn’t include any grand prewar European classics, much to the chagrin of his parents, Tom Sr. and Jean, who often accompanied him to the Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance.

Five years ago, when she was 83, Jean was diagnosed with cancer. “She’s a tough old Italian,” McGough said. “She said, ‘No big deal. I’ve lived a good life.’ And I’m like, ‘Mom, you’re going to fight, and I’m going to pursue a prewar car, and we’re going to restore it and take it to Pebble Beach.’”

Speed was of the essence, so McGough hired broker Ed Fallon to scour the globe for possibilities. McGough considered about 30 cars over six months – Bugattis, Hispano-Suizas, Mercedes-Benzes, you name it. “I wanted something spectacular. But that’s what everybody wants,” he said. “So as soon as one of these big cars comes up, you have to go fight with a bunch of billionaires to acquire it.”

“It” turned out to be a 1937 Delahaye 135 M Compétition, one of only seven cars sporting exuberant coachwork by Henri Chapron described as a roadster cabriolet and the only survivor featuring sumptuous Grand Luxe styling. Among its many owners over the years was Jean Sage, the former head of the Renault Formula 1 program, and it spent a decade in Peter Kaus’ renowned Rosso Bianco museum.

The car was a stunner. For precisely that reason, it was sure to attract a lot of attention. McGough was granted first dibs, but he was given only 24 hours to pull the trigger. Ratcheting up the tension, he had to make his decision based entirely on photographs. “I stared at that thing almost all night,” he admitted. But in the light of day, it was an easy decision because the car was exactly what he was looking for, and he happily paid $1.35 million (£1.1m) to purchase it.

“This car can go toe-to-toe with just about any prewar French car in terms of timeless beauty and rarity,” he said. “It’s not too flamboyant, yet it’s much more sporting than the typical Chapron body styles of that era. I would never say that my car is more beautiful than the [Figoni & Falaschi Delahaye] Torpedoes. But, to me, it’s got this wonderful balance of drop-dead gorgeousness and really tasteful, elegant lines.”

When the car arrived in the United States, McGough thought it looked even better in person than it had in photos. But closer examination revealed plenty of flaws that had to be addressed. Some of the bodywork had been damaged. The wood in the magnificent interior – one of the car’s most attractive selling points – was rotting. Under the hood lurked the wrong engine.

Getting the car to Pebble Beach was going to require more than a 2,000-mile trip from Minnesota to California.

***

Consider the modern supercar. It offers breathtaking performance, exquisite styling, and the most sophisticated technology this side of quantum computing. Yet a million-dollar-plus price tag doesn’t buy you genuine exclusivity. If you were lucky enough to purchase a Porsche 918 Spyder, there are still 917 other owners just like you. Production of the LaFerrari wasn’t capped until 499 cars were sold. Even the don’t-blink-or-you’ll-never-see-one Pagani Utopia is expected to have a production run of 99 units.

But the better part of a century ago, assuming you had the requisite savoir-faire and ample disposable income, you could commission a work of kinetic art that would be uniquely yours. Instead of buying a car out of a catalog or off the showroom floor, you would have a bare chassis delivered to the coachbuilder of your choice. There, a team of artisanal metalcrafters would hammer out – literally – a body built to your precise specifications. Depending on your location and aesthetic sensibilities, you would go to Murphy in Pasadena or Park Ward in London or Pinin Farina in Turin. But it was in France during the depths of the Great Depression that the art of coachbuilding reached its apogee.

“At this point in history, the French were the leaders of design and styling,” said Richard Adatto, who has written extensively about French classic cars. “New developments in art, industrial design, and car styling were all centered around Paris. Harley Earl [the longtime styling czar at General Motors] always came over in October for the Paris show to get ideas and digest what was happening in the styling world.”

As the name suggests, the automotive concours d’elegance was a French invention. By the 1930s, car shows had spread from Paris to the tony beach resorts of Cannes, Nice, and Biarritz. Celebrities, members of the nobility, and denizens of the uppermost strata of European society made the rounds of this circuit to gaze at not only automobile designs but also fashion models and socialites showcasing the latest wares from Parisian couturiers such as Elsa Schiaparelli and Maggy Rouff.

Although chassis could be taken to any coachbuilder, a handful of French companies dominated this rarefied market. Among the most inventive were Russian émigré Jacques Saoutchik, who had fled the pogroms in Belarus in 1899; Carrosserie Franay; Henri Chapron, later even better known for his Citroën DS19 cabriolets; and most celebrated of all, Figoni & Falaschi, which treated automotive bodywork as the canvas for some of the most daring shapes and striking color combinations ever seen. “There was a method to their madness,” said writer and concours judge Peter Larsen, an expert in French classics. “Joseph Figoni saw himself as the great fashion designer of automobiles.”

Inevitably, most of the cars these coachbuilders worked with were French as well. The grandest were Hispano-Suizas, while Bugattis sported the most performance cachet. Delage and, a bit later, Talbot-Lago were also major players in this arena. But a company with a more utilitarian history and far less prestigious reputation emerged as the marque most closely associated with the over-the-top art deco creations of the 1930s.

Delahaye was one of the oldest car companies in France, and, by extension, in the world. Émile Delahaye came of age during the Second French Empire, an era of prosperity and urbanization during the mid-19th century. Trained as a mechanical engineer, he worked as a railway engineer before going into business for himself. By the 1880s, he was building engines of his own design for industrial applications. In 1894, he fashioned his first motorcar, and the year after that, he waded into the burgeoning automobile market.

In 1896, Delahaye entered a pair of two-cylinder gasoline-powered cars in the Paris-Marseilles-Paris city-to-city race – 10 days and 1062 miles over unpaved roads. Sportsman Ernest Archdeacon placed seventh overall, and first in class, while Delahaye himself was 10th and second in class. Accounting for two of the 14 finishers (out of 32 starters), Delahaye’s cars immediately earned a reputation for robustness that stuck with the brand for the rest of its history.

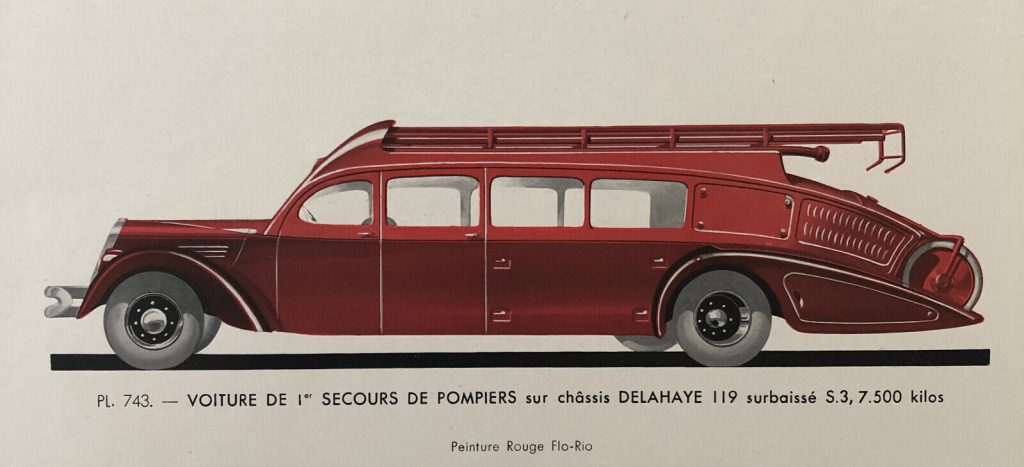

Delahaye sold his eponymous company shortly after the turn of the century. By that time, the two men who would guide the marque for the coming decades were already in place – business/factory manager Charles Weiffenbach, fondly known as “Monsieur Charles,” and technical director Amédée Varlet, who had helped the Edison Company electrify Paris. Although Delahaye continued to dabble in motorsports, even producing an 80-litre (!) engine for boat racing, the company focused on more practical products such as motorised plows and commercial trucks, which performed heroically during World War I. For many years, Varlet’s designs also monopolized the French firetruck market.

There were road cars, too, plenty of them, in every conceivable configuration. But no matter the size or shape, they offered lackluster performance and humdrum styling. Instead, they boasted more pragmatic attributes of sturdiness and reliability at an affordable price. Solide comme une Delahaye – “Solid as a Delahaye” – was the company slogan. But “solid” could just as easily be read as “stolid.” The cars were dependable but boring.

Of course, dependable-but-boring can be a winning formula; witness the enduring popularity of the aggressively inoffensive Toyota Camry. But Delahaye’s bottom line suffered after the shock waves from the American stock market crash of 1929 spread to Europe. Sales of entry-level and moderately priced cars plummeted, compelling the company to look elsewhere to make up for the lost revenue. “Your cars are good and solid but not sporty enough,” Ettore Bugatti supposedly told Weiffenbach. “You have to aim higher.”

The advice was most likely apocryphal. But as fate would have it, Delahaye had an innovative engineer named Jean François working as an assistant to the more conventional Varlet. Before joining the company, François had designed a car with an avant-garde independent front suspension for a small automaker, now defunct, in Lyons. In an effort to attract a more affluent clientele, François created the so-called Superluxe models that were unveiled in 1932. The next year, the Paris Auto Salon brought the debut of the sportier Type 135, which redefined Delahaye’s essential character and ensured the marque’s survival.

The Type 135 belongs on any list of great sports cars. Even in stock form, it was fast, comfortable, and fun to drive – athletic enough for high-speed touring yet stout enough to thrive in the less-than-ideal road conditions of the period. The chassis served as the foundation of some of the most dazzling custom bodywork seen before or since. Yet the car was more than a mere poseur. Competition versions won the Monte Carlo Rally in 1937 and the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1938. The Type 135 remained in production until Delahaye itself folded in 1954.

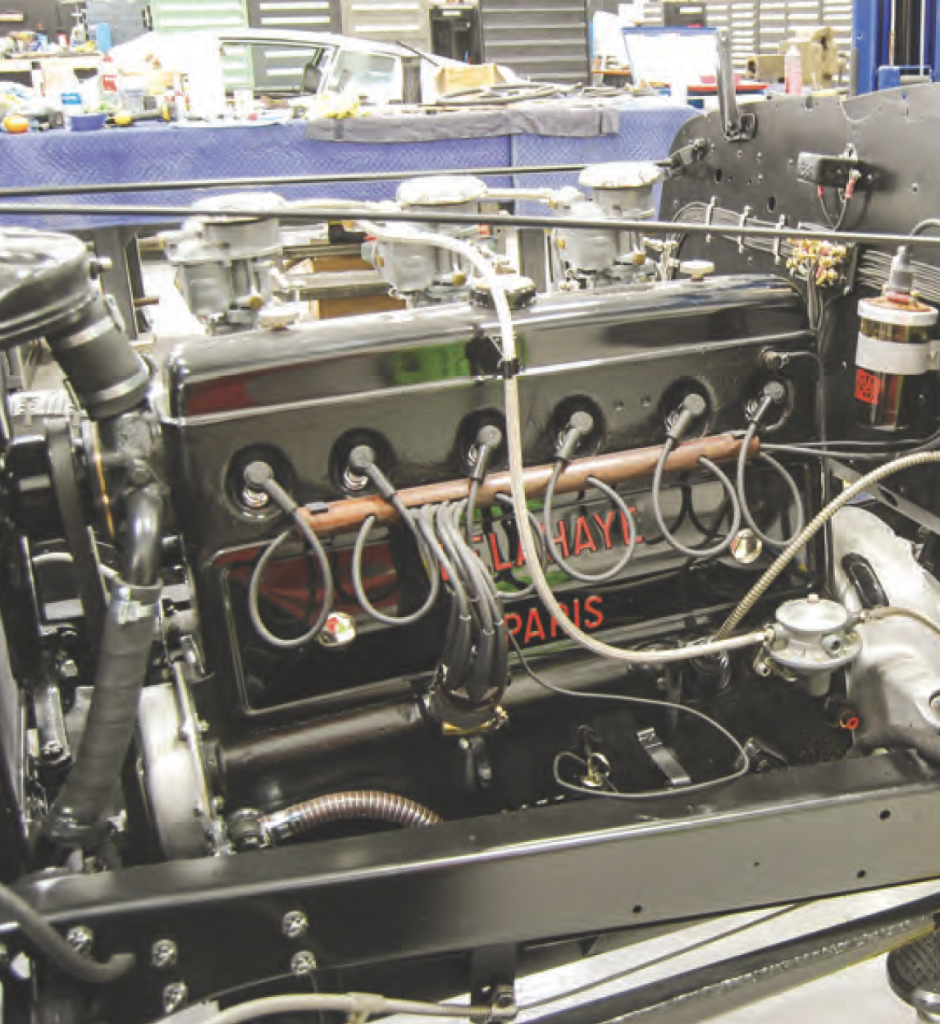

The Type 135 was built upon a traditional ladder-style frame, but with heftier cross bracing than usual. Unlike most cars of the era, the Delahaye benefited from an elementary independent front suspension featuring transverse-mounted semi-elliptical springs and friction dampers. The live rear axle, drum brakes, and worm-and-sector steering were more conventional. Entry-level cars came with a 3.2-litre inline-six rated at 95 horsepower, considered good for the day, though reviewers were even more impressed by the lorry-like midrange torque. Most Type 135s were fitted with an electric four-speed Cotal gearbox – a mechanical wonder that allowed for clutchless shifting.

Inevitably, since the car was designed to be so many different things to so many different people, the Type 135 was offered in a bewildering variety of models – shortened chassis, bigger engines, racing versions, and so on. Enthusiasts generally upgraded to the Type 135 M Compétition, which came with the inline-six punched out to 3,557 cubic centimetres. With pushrods operating two valves per cylinder, the cast-iron engine was considered almost unbreakable (though blocks were susceptible to cracking due to cooling issues). Accessorised with three downdraft Solex carburetors, it made 120 horsepower and transformed the Delahaye into a legitimate 100-mph touring machine. A race version with sidedraft carbs and a special head generated 160 horses.

“There are very few cars which offer such superb road holding and steering, such performance, and such instantly responsive controls,” The Motor reported in a road test conducted in 1938. “The Delahaye is a car which cannot fail to please the enthusiast driver. It should be tried by all those who persist in yearning for the great sports cars of bygone days, and see no merit in modern products.”

For various reasons, Delahaye chose not to build its own bodies. A small number of chassis went straight from the assembly line to coachbuilders such as Saoutchik and Figoni & Falaschi, who used them as the basis for some of their wildest explorations of shape, color, and ornamentation. But what might be called the factory bodies were built nearby in suburban Paris, at Henri Chapron Carrossier, and these tended to be significantly more reserved and less polarizing than the one-off creations from the smaller ateliers.

Chapron had opened his own shop after World War I, making ends meet by modifying Model T Fords left behind by the American Expeditionary Forces after the Armistice. Before long, he branched out to more prestigious commissions, customizing everything from Bugattis and Hispano-Suizas to Buicks and Cadillacs. He was especially celebrated for his work with Delage, which Delahaye bought in 1934. At its zenith, the Chapron factory employed 350 workers and built 500 bodies a year.

Although he was recognised for his refined designs and impeccable craftsmanship, Chapron rarely received the breathless accolades reserved for his more flamboyant rivals. Larsen described Chapron’s design aesthetic as “elegant good taste.” Said Adatto: “Chapron was more conservative. That appealed to buyers who didn’t want a wild body and who wanted an elegant car that would do well at the concours.” He was, in short, the safe choice.

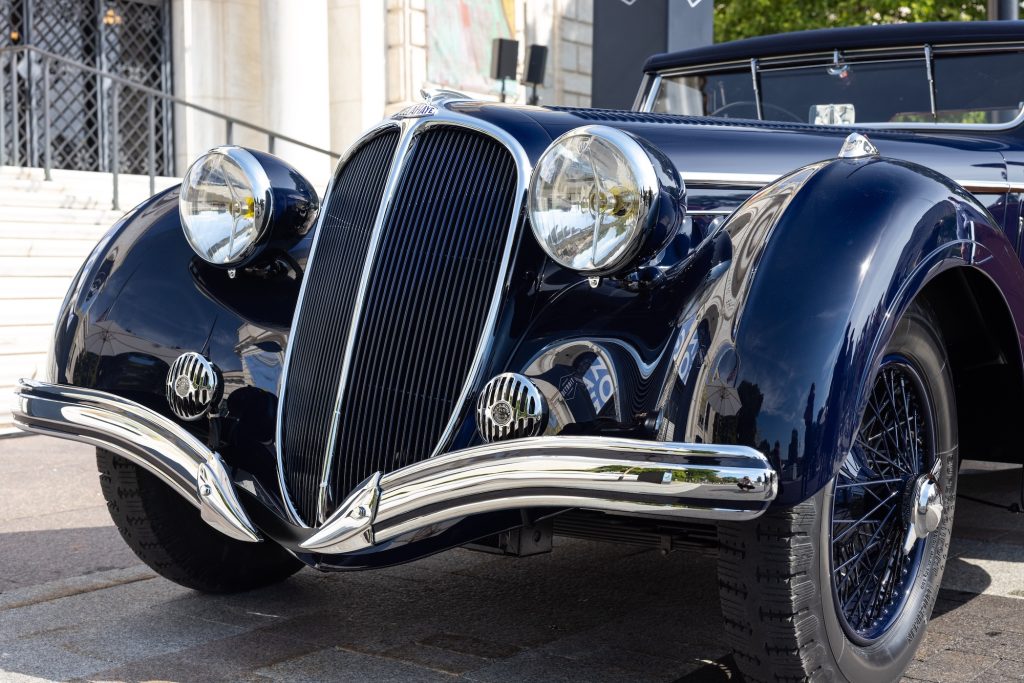

Armchair psychology is always suspect, especially at a remove of nearly a century, but maybe Chapron chafed at his reputation for restraint. For 1937, Delahaye ordered seven low-slung open-top Type 135 Ms confusingly designated as roadster cabriolets. Technically, a cabriolet has roll-up windows while a roadster doesn’t. In this case, the term signaled that the cars combined the flash of a roadster with the comfort (and roll-up windows) of a cabriolet. With a lower belt line than the somewhat stodgy standard cabriolet, the cars were very handsome. But Chapron was determined to swing for the fences. So three of the seven special-body convertibles were done up in Grand Luxe trim, which translated into not only more sybaritic interior appointments but also more dramatic bodywork.

The Grand Luxe version of the roadster cabriolet is a bombshell whose sinuous lines and resplendent ornamentation embody the panache and aplomb that characterize the best of French prewar design. With a steeply raked grille, low-profile fenders, and striking hand-formed rocker panels, the car looks remarkably lithe and graceful, like a leopard poised to pounce on its prey. For these unique touches, Grand Luxe buyers had to pay a premium of about 70 per cent over the “standard” roadster cabriolet. Sold! Chassis No. 47538 was ordered in October 1936 by amateur Delahaye racers Henri Toulouse, who competed under the pseudonym Michel Paris, and Marcel Mongin, who finished second at Le Mans in another Type 135 a few months later.

After World War II, the car passed through several hands before being bought in 1991 by Jean Sage, who’d been the celebrated sporting director of the Renault Formula 1 team when the French manufacturer scored the first grand prix win with a turbocharged engine. Sage later sold the car to Peter Kaus, who enshrined it in his renowned Rosso Bianco collection in Germany. But Sage thought so highly of the Grand Luxe that he reacquired it after the museum closed in 2006. The car was sold to another French collector after Sage’s death.

In 2018, Tom McGough became the eighth owner of the Delahaye. It won’t be leaving his possession anytime soon. “It’ll sell after I die,” he said. “But I’ll never sell it.”

***

“It’s a very pretty car.”

These were the first words out of Mike Kleeves’s mouth after McGough arrived at Automobile Metal Shaping to finally examine the Delahaye he’d bought sight unseen. McGough immediately reached the same conclusion. “I could tell right away that this was a very special car,” he recalled.

The Delahaye looked great in person, which was a relief. Like many automobiles now considered collectible, the Chapron-bodied roadster cabriolet had at one point during its lifetime suffered the indignity of being treated like nothing more than a used car. (There’s a photo of it slathered in mud from an ill-advised wet-weather outing.) But McGough knew it had already been restored once before. He just wasn’t sure whether this was a blessing or a curse.

Restoration philosophy has changed radically over the past half-century. A generation or two ago, shiny bodywork, bold chrome, and gleaming paint were the sine qua non of a great restoration, and it was considered acceptable to upgrade to modern components and contrivances in the interest of functionality. But nowadays, originality is the holy grail, and authenticity is the guiding principle.

As McGough and Kleeves studied the car, they noticed flaws. “The car had been well taken care of, and when we went up and down an airport road adjacent to Mike’s shop, it drove beautifully,” McGough said. But he hadn’t bought the Delahaye as a driver. He wanted a car that could compete for honors at Pebble Beach, and, by that standard, he explained, “It really needed everything, to be honest.”

McGough and his co-owners—his parents and his wife, Megan—committed to a no-expense-spared frame-off restoration. The tan-leather interior promised to be a particular bear. Although the wood lining the cockpit still looked sensational, it hadn’t been sealed, and it was rotting from within. So McGough split the project into two segments. The body and interior would be redone at Automobile Metal Shaping in Morganton, North Carolina, while the chassis and drivetrain would be overhauled at L’Cars Automotive Specialties in Cameron, Wisconsin.

With about 12 employees, L’Cars specializes in American and European classics. Although master metal-worker Blaine Downer had previously worked on several French cars, this was his first Delahaye. He was struck by the durability of the chassis, which was well boxed and welded. (Bugatti, by contrast, preferred rivets.) “I think that they were probably at the cutting edge of chassis rigidity for that time period,” he said.

Although the frame appeared to be undamaged, the artisans at L’Cars found evidence of several modifications, mostly minor. Fortunately, a cottage industry of shops has sprung up to machine and fabricate period-correct items such as fasteners and gaskets, and Club Delahaye in France maintains a supply of hard-to-find components ranging from brake cables to a unique spring-loaded water pump seal. The most glaring upgrade was an electric fuel pump, which obviously wasn’t original. But it was the engine that emerged as a potential showstopper.

During the restoration, McGough was mortified to discover that his 1937 car actually had been retrofitted with a postwar engine. To replace it, he bought a 1936 Delahaye Type 135 two-door sedan—only to learn that this car also “had the wrong fricking engine.” (L’Cars later restored the donor car for McGough as a driver rather than a concours candidate.) Eventually, he found a 1937 block in a small French town, but he couldn’t locate a head. “I was incredibly passionate about making sure my car was correct and numbers-matching,” he said. “So I was sweating bullets at the end there trying to find the right head.”

After nearly two years, largely by happenstance, McGough unearthed what he’d been desperately searching for, in an Austin-Healey shop in England. L’Cars then freshened the engine, having the camshaft reground, redoing the Babbitt-style bearings, cleaning up the valve lifters and followers, and so on. The transmission—a rare four-speed manual rather than an electric Cotal—was in good shape. Worn bushings and bearings were replaced, but the case and the original gears were reused. When the drivetrain was finished, the car, sans body, ran flawlessly on the chassis dyno at L’Cars.

Meanwhile, the body was being overhauled in North Carolina. In years past, when Automobile Metal Shaping was located in the Detroit area, Kleeves did a lot of prototyping work for the big carmakers. Now, with a crew of eight, he specializes in high-dollar restorations and prides himself on using Old World techniques—there’s a forge on the premises, for example—to replicate the work done by the craftsmen of yore. In some cases, ironically, Kleeves said imperfection is the goal. “The louvers on the hood of the Delahaye aren’t arrow-straight,” he said. “Some of them are jogged over two or three mils, and you can see it if you’re studying it. But the judges like that because it’s the nature of a hand-built car. It’s not a CNC-built car.”

Kleeves had to create new sheetmetal for the quarter panels and the tail, and sections of the fenders had to be replaced. Ditto for the bracing for the wood structure. This work was complex and time-consuming but relatively straightforward; body shaping, after all, is part of the company’s name. The big challenge turned out to be the woodwork.

As in many cars of the period, the metal body sits on an ash structure attached directly to the ladder-style chassis. Because the wood hadn’t been sealed back in the day, much of it was now rotting, and joints were weak because the glue had evaporated. A new wood framework had to be built (and sealed with urethane). A more daunting task was recreating the ornate woodwork featured in the dashboard and door surrounds—a breath-taking amalgam of mahogany accented with a walnut burl veneer. “Everybody we talked to said, ‘That’s going to be tough,’” Kleeves recalled. “One of my guys said, ‘I’ll take it on,’ so we did it in-house.”

Although McGough originally thought the car was black, he was pleased to find photographs confirming that it came from the factory in an appealing shade of midnight blue that pops in the sunlight. Kleeves created a wonderfully translucent finish by block-sanding the bodywork before shooting it with five coats of color and six of clear, then color-sanding the paint with eight progressively finer grits of sandpaper prior to final polishing. The convertible top is a slightly lighter shade of blue that complements the body. The car looks as good, if not better, with the top up than it does in roadster form—testament to the purity and balance of Chapron’s design.

Because the whole point of the project was to give his ailing mother a ride in the Delahaye, McGough had hoped the restoration would be done fairly quickly—“quickly” being a relative term in restoration parlance. Trouble finding a correct engine set him back, and then came COVID-19, with all the supply chain delays prompted by the pandemic. But he got some great news along the way. First, treatment left his mother cancer-free. Later, as the restoration neared completion, he received an entry for Pebble Beach in 2021.

McGough was ecstatic. Then a pair of flies threatened to take up residence in the proverbial ointment. First, the trim was running behind schedule, so Kleeves bought a bunch of sewing equipment to do the work in his shop. Even so, the machinery had to be loaded onto the semi taking the Delahaye to Pebble Beach so the top and boot could be finished in nearby Monterey. “I told my team, ‘We’re going to do an all-nighter,’” he recalled. “One of them said, ‘What’s that mean?’ And I said, ‘It means we’re going to see the sun come up.’” Meanwhile, McGough confronted another unwelcome surprise when, shortly before his parents were scheduled to fly to California, his father voiced misgivings about traveling at the height of the pandemic. So even as McGough was obsessing over getting the car finished in time, he had to charter a private jet to fly his parents to Monterey. Which he did, but not without a struggle. “It was hairy there at the end, for sure,” he said.

And then, against all odds, everything magically fell seamlessly into place. McGough drove the first half of the Pebble Beach Tour d’Elegance—the road rally that precedes the car show—with his mother riding shotgun in the Delahaye, while his father enjoyed the return trip. Three days later, the Delahaye received the coveted French Cup, which is awarded to the “most significant” French car at the concours. Last September, after a few “small inaccuracies” were addressed, the car won Best in Show honors at the inaugural Detroit Concours d’Elegance. This year, McGough plans to show the Delahaye at The Amelia.

Naturally, McGough was thrilled. The results justified his decision to invest so much time, money, and energy in a car that wouldn’t have been on his radar as recently as five years ago. But the awards were merely icing on the cake.

“Driving down the spectacular Highway 1 to Big Sur with my mother, healthy, in the Delahaye we’d talked about five years earlier—I have to admit, I was almost crying the whole time,” he said. “I’ll cherish those memories forever.”

Great article about an amazing car and the dedication of Tom McGough in restoring it. Does anyone know why a French built car would have the steering on the right side. Was that a normal Delahaye feature?

Almost all top-end pre-WWII French cars were RHD, even though they drive on the right side of the road. It was felt to be more easy for the driver to exit the car, it was a tradition and it was a tradition or race cars as well. There was not much traffic at the time, so it was not an issue. After WWII, lower and mid-range cars moved to LHD, perhaps influenced by Americans, while the remaining coschbuilders continued to build their traditional layouts.