Richard Tipper has been valeting cars of all shapes and sizes since 1989, and can spend up to a week detailing every inch of a car. He has gone through more cleaning accessories and products than you’ll find on the shelves of an automotive superstore. These are Tipper’s Tips for the Hagerty community.

Engine bays are probably the highest risk area you’re likely to encounter when cleaning a car. A lot of you are probably thinking “well, that’s obvious”, but to some it might not be.

For a start, there’s a bit of mystery as to just how wet you can get an engine bay, as well as where you can get the engine bay wet. To this, the best answer is really, if in doubt, don’t.

That said, modern engine bays are typically very well sealed, particularly with regards to the electrics, which tend to be tucked out of harm’s way.

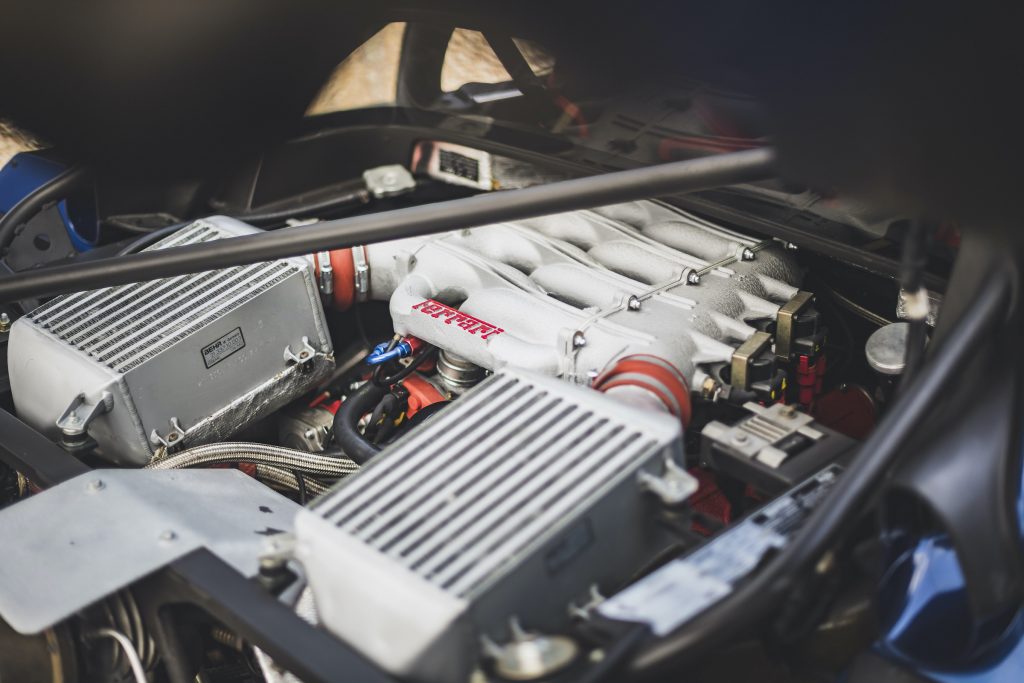

And strangely – though less so when you think about it – mid-engined sports cars are often the safest to clean more “aggressively”. If you think about it, many (particularly more exotic cars like Ferraris and Lamborghinis) have a vented cover over the engine bay to allow heat to escape.

Obviously, that makes it more vulnerable to weather, and if it’s vulnerable to weather then they’ve probably kept the electrics well protected. I’ve actually got more confidence pressure-washing a mid-engined sports car even if the engine is somewhat exposed, for that reason.

There are still some vulnerable parts in certain cars though. Take the Porsche 996 and 997. With these flat engines, the coil packs are on the sides of the engine. They’re well protected from weather thanks to the wheel arch liners, but exposed to heat they can crack, so if you’re forcing water down there with a pressure washer, you can force it into those cracks.

Generally though the best advice is to avoid anything electric, part of the ignition system, or part of the air intake system. Don’t hit any of that with a high-pressure jet of water! You can also help further protect it by wrapping those delicate parts with plastic bags and tape, or even clingfilm.

What really does the cleaning is the product you use – Gunk, Autoglym or whatever – and how you agitate that into the relevant areas, rather than relying on high-pressure water.

Degreasers and caustic multipurpose cleaners are equipped to tackle the grease and oils you’re likely to find in an engine bay. Use brushes to get into the obvious areas, and thinner brushes will get into the harder-to-reach areas.

Avoid using solvent-based cleaners around plastic components, and rubber piping and hoses though, as they can perish rubber in particular. Be sure to rinse off any that comes into contact.

Also avoid the temptation to clean your engine when it’s still warm, perhaps thinking it’ll be easier to clean – it encourages water vapour and subsequently condensation, particularly in areas you can’t reach to dry, and that could cause similar issues to hitting the wrong areas with a pressure washer. It’s all water in places you don’t want water to sit…

You can though start up the engine after cleaning, first to ensure it’s still working, and second to burn off any excess moisture in areas you can’t get to. You can use high-pressure air or even a hair dryer to dry inside nooks and crannies.

It sounds obvious, but older engines can be quite different to newer ones too. Their electrical components tend to be less well sealed. Spark plug holes are more exposed, as are coils and distributors, so you don’t want to be forcing water around those areas. If any water does get down into the plug holes, try and soak it up with a tissue, or a vacuum cleaner. Blowing it out is possible but can also force water down past the threads, so isn’t recommended.

The air intakes tend to be more exposed on older cars too – think of that big funnel airbox on top of a Mini’s carburettor – so it’s worth plugging up that gap with a piece of a rag, or wrapping a latex glove over it or similar.

Old fuse boxes don’t tend to be well sealed either, and whether pressure washing or generally cleaning, try and avoid forcing water and products into areas that are designed to be lubricated, such as bearings, throttle linkages and the like. If you do end up washing away grease like that, make sure you have some handy to replace it.

If your car does have a distributor, after cleaning remove the cap and dry up any moisture you find. While you’re in there, it’s worth cleaning the contact points too, with a bit of emery paper. If you’ve got a flathead screwdriver handy, you can use that to straighten out bent radiator vanes too – so you might even find your cooling improves.

As for dressings, I use a product called GT 85. You can find it in the cycling section of places like Halfords as it’s a very effective chain lube, but it leaves a very thin film of PTFE, or Teflon if you’re more familiar with the trade name, over everything exposed to it. If you follow me on social media and have seen the before and after photos of engine bays, you’ll be familiar with the effect!

When you warm up the engine it’ll burn off, with a few whisps of smoke, and then you can wipe it all over with a microfibre cloth. It’ll leave the surfaces treated, and dressed, but it won’t have that kind of fake, cheap, shiny silicone finish.

Be mindful that some cleaning and dressing products are flammable however, and you’re putting them onto an engine that will tend to be quite hot! But in 33 years, I’ve never had an engine catch fire. You just need to ensure you remove any residue.

Oh, and as an aside, you can use that GT 85 product to lubricate the bonnet hinges too. And it shouldn’t need to be said, but never let the bonnet or engine cover slam down! You can bend it, you can snap the locking mechanism, and you might not be able to open it again. Either let it drop from a few inches above the catch, or leave it on the catch and push it down carefully above the latch.

Read more

Elbow Grease: Sprucing up a dirty dashboard

When it comes to protecting your hands, do your work gloves actually work?

Socket Set: How to clear drainage channels and stop your car leaking and rusting