From the outside, the Porsche 356C looks just as it did when it left the Zuffenhausen factory in 1965. Erwin Komenda’s curves are perfect, its chromework immaculate down to the twin tailpipes protruding from the rear bumper guards. A car restored to the highest quality.

Open the door and the same is true of the cabin. Although the red leather seats, dash, and door cards are perhaps more lavish than when the car was originally delivered, not a thing is out of place. Three pedals and a four-speed manual transmission take the floor.

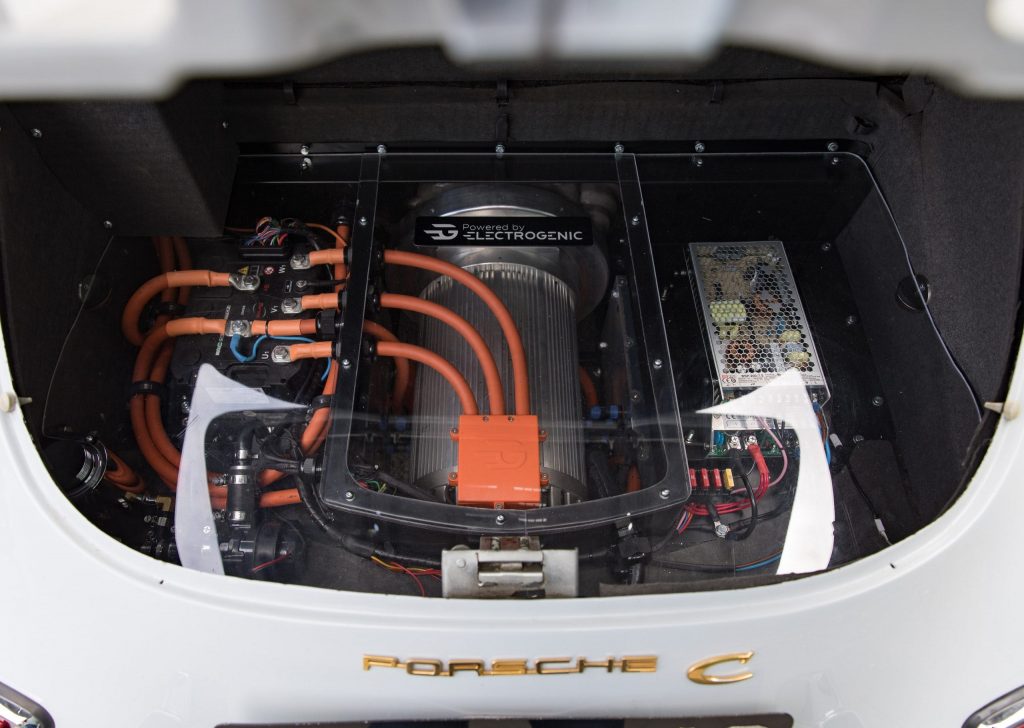

Open the engine cover though, and you’re in for a big surprise, because the 1.6-litre four-cylinder boxer is long gone. In its stead is an electric motor and ancillary control units, proudly displayed beneath a plexiglass cover. In the ‘frunk’, a battery box takes up all available space behind the spare tyre.

The conversion is the work of Electrogenic, a small British firm based near Oxford, and the precision engineering that has gone into it is plain to see. Rather than focus on a limited number of classics to resell as turnkey EVs in the vein of Lunaz or Everrati, Electrogenic has built a modular system that can be applied to almost any car built before 1985.

Having built 14 wildly different vehicles over the last two years – from VW Karmann Ghias to Triumph Stags, Jaguar E-Types, Morris Minors, Porsches, and early Land Rovers – Electrogenic can offer a wide range of power, charging, and performance options, all controlled by the company’s own systems. While every car so far has been different there’s one thing they have in common – each conversion can be reversed, as no body or chassis parts are cut away in the process.

Steve Drummond, Director of Electrogenic, explains: “Broadly speaking it’s as follows. If you want to use a manual gearbox, then you need to have a motor that doesn’t rev too high and in terms of what’s available at a reasonable price, then the go-to motor for that is a Hyper Nine. It’s got 235Nm [173lb ft] of torque, a maximum 10,000rpm, and it runs at low voltage, but you need a gearbox to actually make it into a decent car. As it’s low voltage you can charge it up very quickly on a public charger.

“If you don’t want to keep the manual transmission, then you’re going to have a high-torque motor. So if you look at a Tesla, it’s got a massive motor, which has got really high starting torque, and it revs to 18,000 rpm, so that you get fast acceleration off the block and a high top speed. So they tend to be 350 volt systems. And those motors are more expensive. But then the transmission is cheaper, because you haven’t got to develop a flywheel and clutch to make the gearbox work smoothly. So it’s it swings and roundabouts. Really what it’s about is, how do you want your car to drive?”

For the most part Electrogenic’s goal is to retain as much of the original feel of the car as possible, maintaining weight and its distribution as close to standard as possible. Unless the customer has other ideas…

One of the cars currently in the workshop is a TVR Cerbera which the owner wants to be turned into “a track monster with a 15-minute recharge.” There are also a couple of 911s in progress, one of which is a “steampunk version” with a huge amount of power, and a Lotus Eclat which previously had a Rover V8 in it and will be getting an equally gutsy electric heart.

At the other end of the scale, eight Minis are in production for a London tour company. A mint MGA will soon be running again, nearly silently, three Land Rovers have been built for the Glastonbury estate, and a Morgan and a Citroën DS are already gliding round the countryside under Electrogenic power.

When it comes to cost, each project is unique. The cheapest full conversion for a Mini is currently in excess of £30,000, while the pretty Porsche 356 ran somewhat higher. One customer specified a particular Swiss drive motor which cost over £23,000 on its own.

There are early signs that Electrogenic’s future-proofing may also prove to be a wise investment. Demonstrator cars have been sold for the price of an equivalent internal combustion–powered model plus the cost of conversion and a little more. The 356 is being offered by its owner at around £140,000, or about £14,000 more than a concours example of its boxer-engined relative.

Whether you consider what is gained by the conversation worth more than what is lost will be a personal choice. In the case of the 356 there’s about 25 per cent more power than before and a modest weight penalty of 35kg. The rattle and thrum of combustion is replaced by the refined whirr of electric motors and the intricacies of double de-clutching and rev-matching gearshifts are no longer necessary. For some, that’s a luxurious plus; for others, a less involving driving experience is a less magical one.

The 356 is now, effectively, two cars in one. You can drive it all day long in third gear, where it will pull strongly from a standstill all the way to the legal speed limit, riding a wave of electric torque. Or you can row through the gears and experience acceleration that would suit a race track.

In first gear the Electrogenic-converted 356 is seriously rapid off the line, even out-dragging a Porsche Taycan in the company’s tests until it was time to change up. Gear changes feel a little ponderous at first but after a few laps of the short track at Bicester Heritage I begin to get a feel for it. There’s no one-pedal driving here; the brakes do provide regeneration but only once firmly applied, and though there’s a temptation to heel-and-toe on downshifts, it would bring no benefit. The little Porsche’s agility seems unaffected by the modest increase in weight and while there’s a little more mass over the front axle (the split is now about 40:60 front to rear) the steering is still light and communicative.

Did I miss the sounds and smells of combustion? Maybe a little, but mostly I came away with the feeling that this is a classic car made even more useable. The 140-or-so-mile range would require considered planning for grand road trips, but it could easily be a daily driver, as many of Electrogenic’s conversions already are.

“The big thing about the conversion, apart from being quicker, is that it’s just more relaxed,” says Drummond. “You don’t have to worry too much about being in the right gear, but the gears are nice if you want to drive quickly – they allow you to do that and give you the experience, but you don’t have to stress about it.”

Via Hagerty US

Read more

Why electric power was the answer when this 1958 DKW expired

Rematch: Porsche 911 Carrera vs 944 Turbo

11 classic cars that deserve a modern comeback

For my part, to me, a classic car represents a nuts and bolts machine with a mechanical beating engine at its heart. It’s a hands on experience, not too relaxing to drive, maybe not all that fast by modern standards but it’s how i love it, the whole package, and driving experience. It’s what it’s all about. To take away part of it is like ripping the soul out of it. Electrification may well be the modern way but the selling points like quiet, super fast, smooth and relaxing with quick charging sounds more like driving an electrical gadget. Not like a true classic experience in my book.

An electric classic is no longer a classic.

For those who describe classic cars that have been converted to electric power as no longer being ‘classic’, do they also argue that historic cathedrals which now have electric lighting and heating are no longer proper historic cathedrals?