Welcome to Freeze Frame, our look back at moments from this week in automotive history.

20 October 1968 – Mazda’s makes its competition debut at the Marathon de la Route on the Nürburgring

The pioneering spirit of Japanese automobile brands in the 1960s matched anything from the early days of motoring. Growing rapidly from Japan’s postwar economy, companies like Honda and Nissan thought little of jumping feet-first into new markets or breaking into top-flight motorsport. Every new opportunity was to be grabbed by the scruff; every new technology something to explore. And that was how Mazda came to compete at the gruelling, 84-hour Marathon de la Route at the Nürburgring in October 1968.

Mazda was perhaps the most experimental of an already experimental bunch of Japanese carmakers. As the Toyo Kogyo Cork Co, it had survived the atomic bombing of its home city of Hiroshima in 1945 on a wing and a prayer, its plant protected from the brunt of the damage by the nearby Ogonzan hill.

It was also quick to capitalise on postwar market conditions. When the government expanded Japan’s kei-jidosha light automobile regulations to allow 360cc engines (originally, in 1949, the limit had been just 150cc), Mazda produced the tiny R360 coupe. It dominated the market, achieving a two-thirds share of the class and a full 15 per cent of the entire domestic car market in the country.

But Mazda is best known for its Wankel rotary engines, licensed from NSU in the 1960s. Echoing Honda – whose very first car was a roadster, the S500 – Mazda’s first rotary production car was the Cosmo, or 110S, a compact and waif-like sports coupé.

While its on-paper stats were impressive, and the car attractive, the public was sceptical of the rotary engine’s qualities. They were seen as fragile, despite rave reviews from magazines like Motor Sport, who praised the smooth-spinning, 8000rpm engine in their April 1968 issue.

“After one particular ‘demo’ on local race-tracks,” wrote the magazine’s Denis Jenkinson, “…with the engine being kept up around 6500-7000rpm all the time, we got back and were very impressed with the way the engine just sat there ‘pobbling’ over at its usual 750rpm tickover as though it had only just been started.”

Nevertheless, the public’s scepticism was a view Mazda was keen to turn around if its rotaries were ever to taste sales success. An 84-hour race around the world’s toughest racing circuit isn’t perhaps the route most would choose, and it certainly wasn’t going to be easy. Not just to compete, but to even finish – but if it did, the rewards could pay dividends for Mazda’s rotary road cars.

Mazda prepared heavily, running long-distance tests at the firm’s Miyoshi Proving Grounds under the watchful eye of Kenichi Yamamoto, “father of the rotary” (and later, the man to whom Bob Hall pitched his idea for the Mazda MX-5). The racing motors, displacing just a litre, developed around 130 horsepower, 20 up on the road cars, and uncorked the engines were fiercely loud.

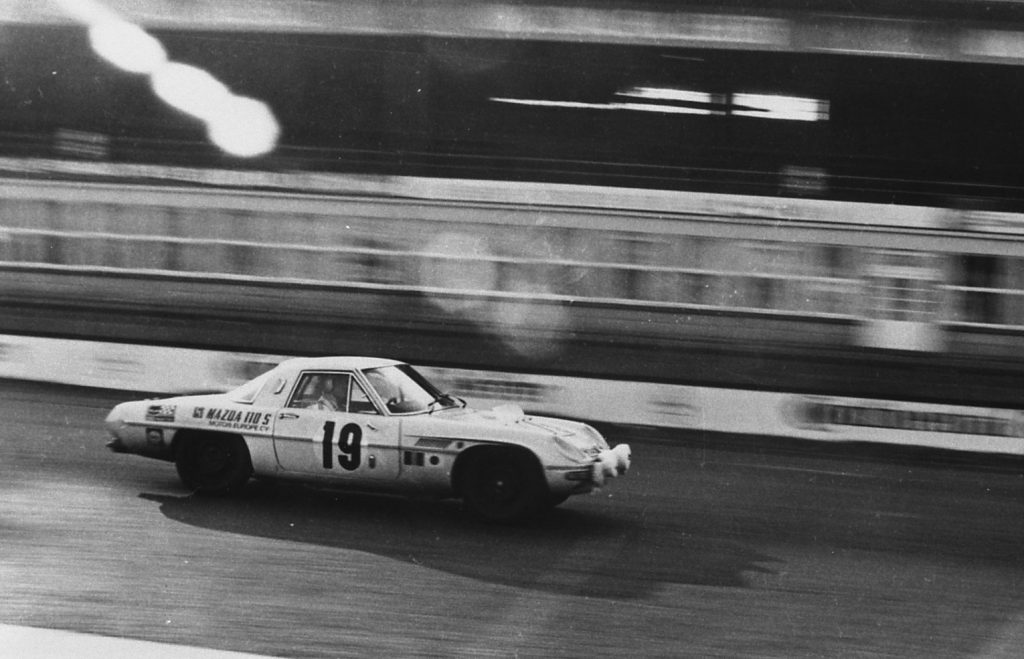

Two Cosmos took to the grid on October 20th, 1968, one driven by an all-Japanese lineup including Nobuo Koga – who had driven an Honda S600 in 1965’s Marathon – and the other an experienced trio of Belgian drivers. Rain marred the start, but as the weather cleared the order settled, Porsche and MG duking it out for the top spot and both Cosmos running strong a few places back.

Eighty hours in it was looking almost like a dream finish for Mazda, with cars running fourth and fifth, but in the 82nd hour an issue with a rear wheel pitched the Japanese-driven car off the road and into retirement.

The other car, though, finished to cross the line fourth. While 12 laps off the winning Porsche (joined by another 911 and a Lancia Fulvia on the podium), Mazda had proven the durability of its car, and more importantly, its rotary engine, after more than 6000 miles and three and a half days of flat-out driving.

And sales success? Well, the Cosmo itself never sold in enormous numbers, but in later years Mazda would indeed turn the rotary into a success, until environmental regulations finally called time on the RX-8 in 2012.

Most successful of all was of course the Cosmo’s true sports car descendant, the RX-7. Nearly half a million first-generation models found homes between 1978 and 1985, and by the time the third-generation ‘FD’ ceased production in 2002, that number had risen to more than 800,000. The rotary wasn’t without its faults, but as the 1968 Marathon de la Route showed, it was a small engine destined for much bigger things.

Read more

Freeze Frame: Honda’s Grand Prix debut

Buying Guide: Mazda MX-5 Mk1 (1989 – 1998)

The Flying Wrens: All-female dispatch riders of WWII

Excellent piece. Many years later, in the early 1990s, I went to Hiroshima and interviewed Kenichi Yamamoto, Mazda’s former president and later chairman for AutoWeek. When I mentioned he was the “father of the rotary,” he demurred. “No, I am the godfather, ” he said, as he didn’t invent the engine himself but leading a highly motivated Mazda R&D team, he perfected it better than anyone else. Yamamoto remains one of the great figures of Japan’s postwar car industry, and more than anyone, helped create the modern Mazda DNA.

Thank you Peter, and not surprised Mr Yamamoto was so humble about his involvement. Definitely a hugely important figure.