Watching a full-size adult in period costume whizz around a race track in their homemade pre-war style miniature automotive is a charmingly incongruous spectacle, but when engineer Jim Tanner saw cyclekarts in motion for the first time he wasn’t content as a spectator. Within months he’d “knocked together” his own lightweight, single-seater machine using a pull-started, air-cooled, 200cc Honda GX four-stroke engine and a little imagination.

The cyclekart hobby emerged in America during the nineties.“ It caught Tanner’s eye. If I like something, I like to be involved,” says Tanner, who, as a school boy, was inspired to build his first go-kart – with twin chassis rails, six-volt battery-powered lights and hand-painted flames – by a “Bugsy Malone-esque” car he’d seen on an episode of Blue Peter.

With running repairs, Tanner’s childhood chariot just about survived the summer holidays, but the project stands out as the one that ignited his passion for “messing around with cars” and equipped him with a foundation of knowledge which helped him with DIY car mods down the line before graduating to designing and building his own hot rods, as well as a slingshot dragster that can do 0-60mph in 0.9 seconds.

“I’m of the make do and mend generation, and follow that sort of philosophy in life, so have always loved making stuff, particularly engines,” says Tanner. “With cyclekarts, there are a few rules and guidelines to follow, but I love the creative side of them. 90 per cent of mine is made from bits that I’ve found in charity shops or lying around the workshop – I always see potential for things to be used as something else.”

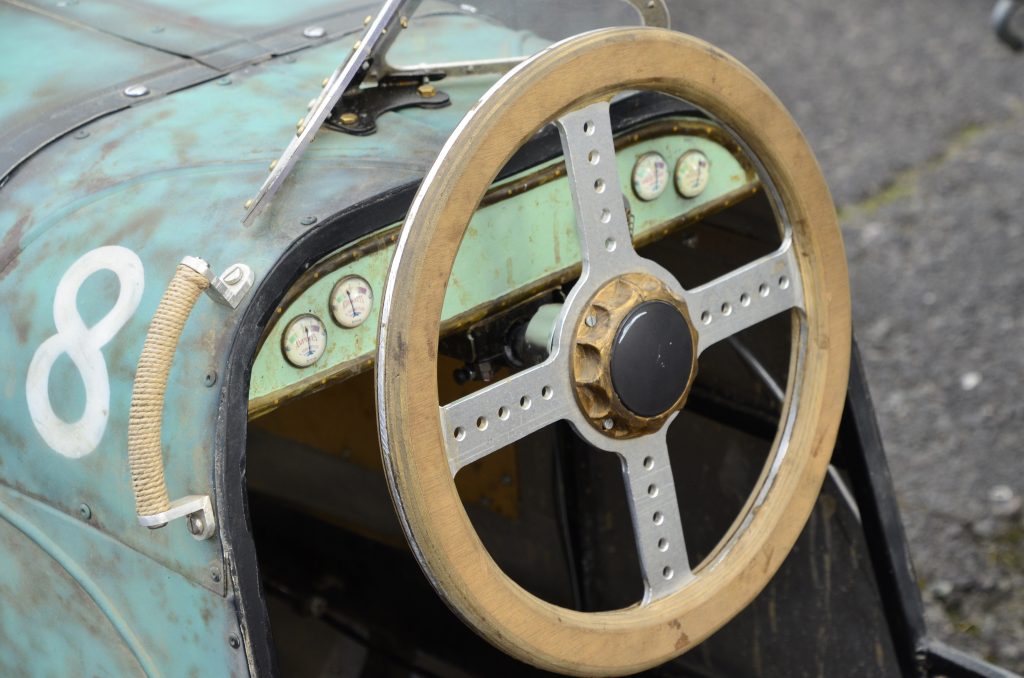

Identifying what the upcycled trinketry on the cyclekart used to be requires a closer inspection, and a little explanation. “The bezel around the air vent into the engine is made from an old aluminium tax disc holder, and the handbrake handle is made from an old wooden file handle,” Tanner reveals. “It was the right shape and saved me carving one from scratch.”

Other ingenious features include the steering wheel’s black and gold centrepiece (a broken shower dial in disguise) the rear light surround (a bell) and the brass studs that hold the bucket seat’s upholstery in place (paper fasteners). Just brilliant.

Also dressed up to look the part (in flying goggles and a jet helmet) he pilots number 8, the two and a half metre long 1935 Dodge Baquet Cyclekart he built at home in his garage, in “drive it like I stole it” fashion.

Sweeping along straights at a top speed of approximately 45mph, before gleefully attempting to get a drifting tyre squeal out of every corner, the grin on his face says “join me”, rather than “think you’ve got what it takes to race me?”, because as high octane as this all sounds, the ethos of hurtling around a circuit in a cyclekart is more gentleman driver in pursuit of excitement on a shoestring budget than all-out splash the cash competition.

“Not everyone wants to do 200mph, but as soon as you mention to people that you can go around a track their eyes widen because a lot of people would like to be able to race for fun but it’s unavailable to them financially,” says Tanner, who is a member of Cyclekarts GB, a group set up by British enthusiasts to share advice and technical support. “We do have timed laps and drive enthusiastically, but it’s not about racing and we’re certainly not interested in bashing into each other,” he adds.

To succeed at building a certified cyclekart, Tanner had to make himself familiar with the Stevenson formula, which outlines limitations to wheelbase, drivetrain and mechanics in order to cap vehicle performance so that a fair and light-hearted level of competitive fun can be maintained. This, he says, gives cyclekarts their universal “Heath Robinson” appeal.

Named after Peter Stevenson, the man who invented cyclekarts, the guidelines are followed, loosely, by builders, and although there’s no official governing body in the UK – cyclekarts is not yet a recognised motorsport – Cyclekart GB regulations state that vehicles should have a maximum wheelbase of 1800mm, be powered by an unmodified Honda GX200 (or clone) engine with a peak output of 212cc 10hp and run on open 14-17 inch spoke wheels. “We do bend the tuning guidelines a little,” says Tanner. A cut off switch should also be clearly visible and no head or camshaft modifications are allowed.

“There’s no official committee, we’re just a group of friends, so we self-scrutineer,” says Tanner, who can boast several podium wins at club competitions. “Before an event we do a check of spokes, nuts, bolts, chains and brakes as well as a general go over of the car.” The “rules” also suggest the weight of the vehicle should not exceed 125kg, and that if requested, drivers must be able to provide evidence of their vintage inspiration car in the form of photographs and/or articles.

“I wouldn’t criticise anyone if they wanted to build their own design, in fact I’d applaud them as long as it fits in with the ethos that it needs to look like a pre-war car. You do get some purists, but I think the British, more so than the Americans, are trying to push the boundaries so that they can make higher quality vehicles and move away from the Stevenson formula.”

His method may not be as orthodox as some (he’s not a man for setting aside too much time for technical drawings) but working from measurements he took from a simple concept sketch “with satisfactory proportions” he was able to build a cyclekart that stands up to aesthetic and operational scrutiny. Paying homage to a “rusty” 1935 Dodge Baquet he found photographs of on the internet, Tanner estimates it took almost 40 metres of welding to form the body and chassis out of laser-cut and shaped sheet metal.

Under its skin, Tanner deviated from the standard torque converter setup by fitting a centrifugal clutch which provides a fixed gear ratio of 12 to 1: “it doesn’t give me a huge amount of top end,” he says. “But, it does make it a bit quicker out of the corners, which I quite like.”

Thanks to his canny approach to engineering using upcycled items Tanner was able to keep his build cost to £650 (the average spend is between £1500-£2000 using new and good quality components) and it won’t be too long, he hopes, before he will be selling his own bespoke range of bespoke cyclekart parts – including a fish tail shaped exhaust silencer – so that he can make a useful contribution to the growing cyclekart community and encourage those with less engineering experience to have a go.

“I’d love to inspire more youngsters and women to get involved, it is a real dream for me,” he says. “Cyclekarts are a project that parents and children can get stuck into together, and they fit easily into a single car garage. I want people to enjoy it as much as I do, the more karts we have out on the track the more spectacular it looks and the more fun it is.”

Second only to his Harley Davidson, Tanner’s cyclekart turns the most heads when he’s out and about, and has been known to make crowds go “berserk”.

“I took it to Johnny Smith’s The Late Brake Show tour in Market Harborough. There was me driving around the little snowfield and Johnny was getting quite excited, shouting ‘look at that thing!’,” he recalls. “When I went to Brooklands with the Cyclekarts GB group it was as though Tazio Nuvolari himself had turned up. The waving, the clapping and the cheering was so great that the organiser made us go round and do it all again.”

Not that he’s complaining.

Read more

Hard Craft: Joyride Jewelry

Hard Craft: Pete Oldham, furniture maker

Hard Craft: Ramón Cubiró’s marvellous miniature slot cars

Really interested in cyclekarts, going to start build based on the old frog eyed sprite, where is the best pace to get leaf springs from and wnhaty are the rules on chassis size

I’m very interested in getting hold of a rolling chassis with the geometry and braking done – instead of paying school fees from scratch. I’m very keen on building my own body and installing a 10hp electric drive to make the project my own. Any options here? I’m a patient man

car looks great is it possible to buy one second hand thank you