With a subtle tip of his Stetson hat, Todd Sanders says hello. It’s a kindly, respectful, gesture. He’s a mellow and unassuming man. Not a cowboy, nor a rancher, but an artist, with a milky, laid-back southern drawl. “I was born in a small town in east Texas,” he says, “but I was always fascinated by the expanse of the open road. The world unfolds ahead of you.” His slow talking helps set a provocative scene; setting the car to cruise control as you cross a shimmering sun-bleached desert beneath a big sky.

“When I was 16, my dad and I took off to Arkansas,” he cheerily recalls. Sanders’ parents, at the time, had recently divorced. “We figured our way there and back using maps.” They figured a few things out about each other, too. “If you really want to get to know someone, go on a road trip with them, because good or bad, you’re going to know who they are after a few hundred miles.” Was it revelatory? You betcha, but not just because of the frank talking between father and son. “I fell in love with the old gas stations, diners, and cafes we saw on the highways.” Their iconography, he romances, stirs a sense of nostalgia for the classic all-American experience.

“Neon came to America in 1923 from Paris,” Sanders says. “Over there it represented the height of opulence, but, here in the US we turned it into something that’s truly our own – think cartoon dogs with a wagging tail.” Have you seen the giant dachshund gobbling frankfurters on Historic Route 66? Sanders refrains from using the word tacky. “In their heyday, everyone in town had a neon sign, from the police department to the mortuary and exterminator.” The most unusual he’s seen lit up a store for prosthetic legs. “They can be macabre but still fun, and to me, always beautiful.”

After making an inconspicuous debut to flaunt a car dealership in Los Angeles, neon illuminations blazed a path across America during the first half of the 20th century. From the casinos of Las Vegas – back then a fledgling city of entertainment – to the art deco hotels of Miami’s South Beach and the iconic billboards of New York’s Time Square, the novelty of the science-driven art form captivated a generation. Crowds gathered to witness the latest switch-on, the moment when physics and chemistry collide. “I don’t think people understand how neon works, but they feel it,” Sanders says. “Like a full moon or a campfire, it’s somethin’ on a primal level that you really feel.”

The technical explanation is this. “Neon is a noble gas that occurs naturally in the atmosphere,” Sanders explains. Traces of it can also be found in the Earth’s crust. “When an electric current passes through it, the ions inside the gas get excited and glow.” They turn a retina-searing orange-red. For this reaction to occur, the neon has to be placed into a vacuum, which in this context is a sealed glass tube. “The aurora borealis is a bunch of noble gases that are ignited, like neon signs, so that’s why there’s something about it that speaks to us on a primal level.”

It’s on a lonesome highway in the middle of the night that neon can have its most profound effect, Sanders suggests. “It’s a beacon, it beckons you in.” Think of the relief a weary traveller might feel when they see the motel sign flashing “Vacancy” without the “No.” By the 1950s, though, plastic lighting had arrived. “Neon was vilified,” Sanders says, a hint of anguish in his voice. Scrapped, neglected, and in many areas banned, neon displays became an endangered commodity. “I’ve heard stories of people with shotguns standing outside their property saying ‘you’re not taking my sign.’”

Sanders took a less confrontational approach to saving the medium. A college dropout living in a 1950s trailer, he set up the first vintage neon sign company in the US. It was 1995 and he named it Roadhouse Relics. “I grew up in my dad’s welding shop,” Sanders explains, “but I always wanted to be an artist. I lost my nerve when I got out into the real world and painted cars in Southern California for a while.” His story turns a little melancholy. “I came back to Texas.” But the homecoming wasn’t a full-stop.

Painting signs to pay for his tuition at Sam Houston State University, where Sanders studied Fine Art, “was a step in the right direction,” but it was missing a turn and ending up in Austin during a spring-break road trip that sealed his creative fate. “I saw the neon signs, I felt the vibe of the city, and I said this is what I want to do, and this is where I want to move to. It took years to learn my craft.” But it didn’t take long for Sanders’ talent to be noticed. Two of his earliest pieces, depicting the Mercury Man with a winged helmet, were commissioned by the actor and musician Johnny Depp. “I would have carried on anyway, but the validation felt great. To see someone’s response, someone’s emotional reaction, is the real payment.” In actual terms, Sanders’ pieces range from $5 to $35,000. He doesn’t do commercial work but his mix of one-off commissions and limited runs are coveted and shipped worldwide. Willie Nelson, Joe Rogan, and Billy Gibbons are all clients.

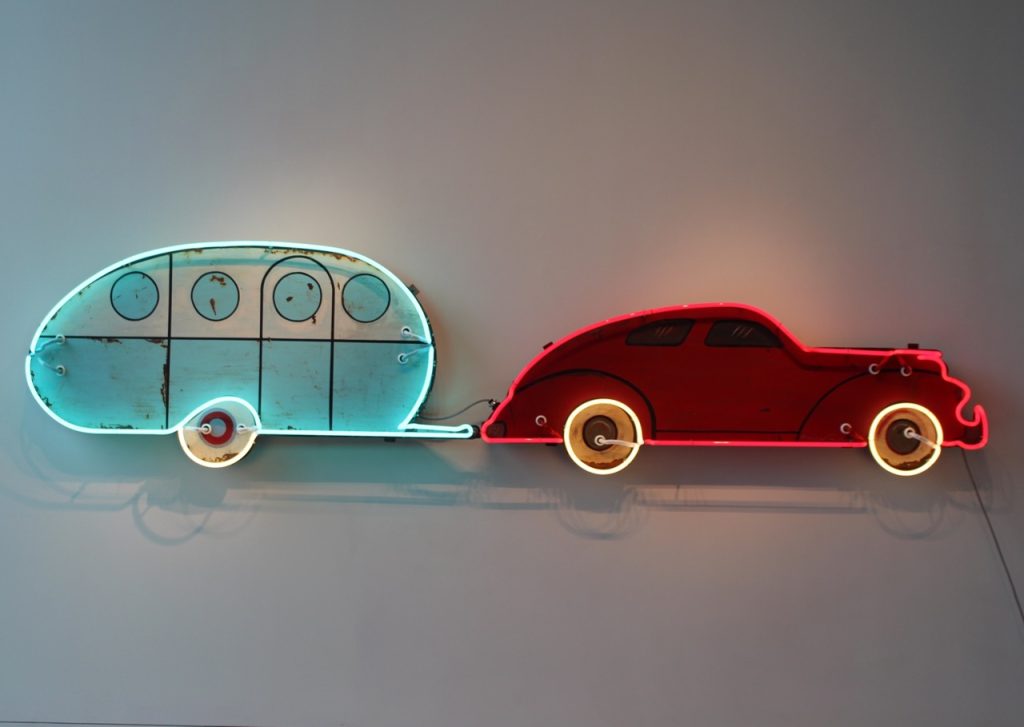

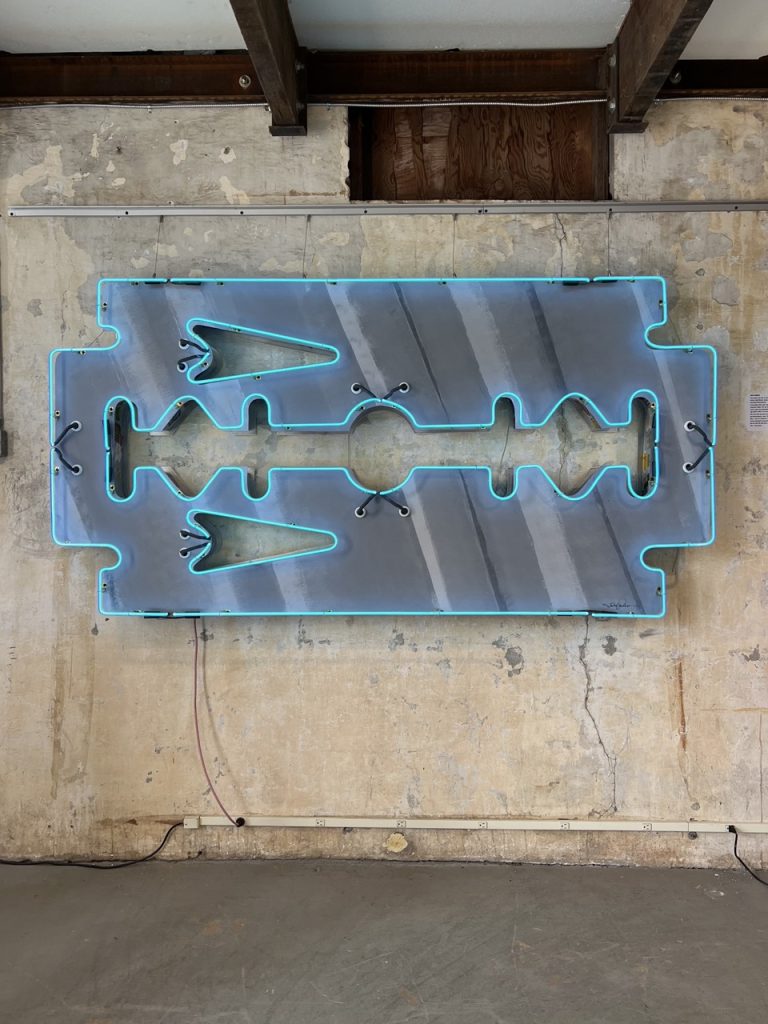

From a mason jar alive with fireflies that flicker on and off, to a buxom tattooed mermaid with a swishy tail and sweeping scarlet hair, Sanders’ installations are whimsical, sometimes mythical, and always fun. They’re also a feat of ingenuity. The most ambitious so far is a 30-foot mural that tells the saga of a family’s life. Set against a road map that he painted to look like parchment, this neon biography, “one of the most meaningful but hardest pieces I’ve ever done,” features an animated Native American drawing back a bow as well as a volcano mid-eruption. “All these neon artworks had to communicate with each other,” says Sanders, who uses a device called a transformer to control the transfer of electric energy from one circuit to another. This is how he’s able to make elements flash. “It was tough to get it all wired and I thought, man, I hope I got all this right. But when I turned it on, it glitched for a second, and then the Indian started shooting the arrow from his bow. I was exhausted, I was sweaty, but it never stops captivating me when I light one of my pieces up for the first time. I’m a little boy again.” (Sanders’ earliest memory of neon is of a turquoise-and-pink clock that he saw outside a BBQ restaurant when he was 2 years old. “I know it sounds crazy, but that’s when I fell in love.”)

It can take weeks to develop a new concept; a sign he made for the band Kings of Leon went through 27 different iterations. “After 30-something years, coming up with a new idea is the toughest part,” Sanders admits. He finds inspiration in lyrics and on long drives, and for the latter he can choose between his ’51 Mercury or ’59 Chevy pickup. “The rest”, i.e. the making, “is elemental,” he says, and can be completed in four to six weeks. During this stage of creative flow, Sanders spins old records on a ’50s jukebox or plays old movies on a loop. “For the most part, I just listen to the old movies because I’ve seen them before and that means I don’t have to take my attention away from what I’m doing.” His is a tidy and soulful studio, which of course has neon artworks on its walls.

The journey of their creation begins as a hand-drawn design on gridded vellum – a type of tracing paper. “There’s a lot of pushing markers [pens] around to refine the sketch. I could go a lot faster if I worked on a computer, but that human touch is what people connect with; each piece represents a small portion of my life.” To see what a design looks like to scale, Sanders uses a projector to display it on the studio wall. From there, he’ll create a pattern for the neon sculpture as well as the metal upon which it’ll be mounted.

To shape the neon tubing into letters, lines, and forms, Sanders collaborates with a specialist glass blower – a bender, for those in the know. After being heated and set into position, a metal electrode is fitted, and air and impurities are removed using heat in a process known as bombarding. The tube is then filled with classic neon or alternative noble gases, such as argon, which omits a mesmerising celestial blue. To achieve a full spectrum of colours, Sanders favours tinted glass.

What really ignites Sanders’ neon, however, is the 20-gauge (0.9mm) steel canvas upon which it hangs. “This is my art, made my way,” he says. Painted with a signwriter’s enamel and weathered using a technique involving Scotch-Brite, elbow grease, and a vinegar solution that he developed himself, the result is a new piece that looks authentically retro. It’s an aesthetic that pairs perfectly with neon’s nostalgic appeal.

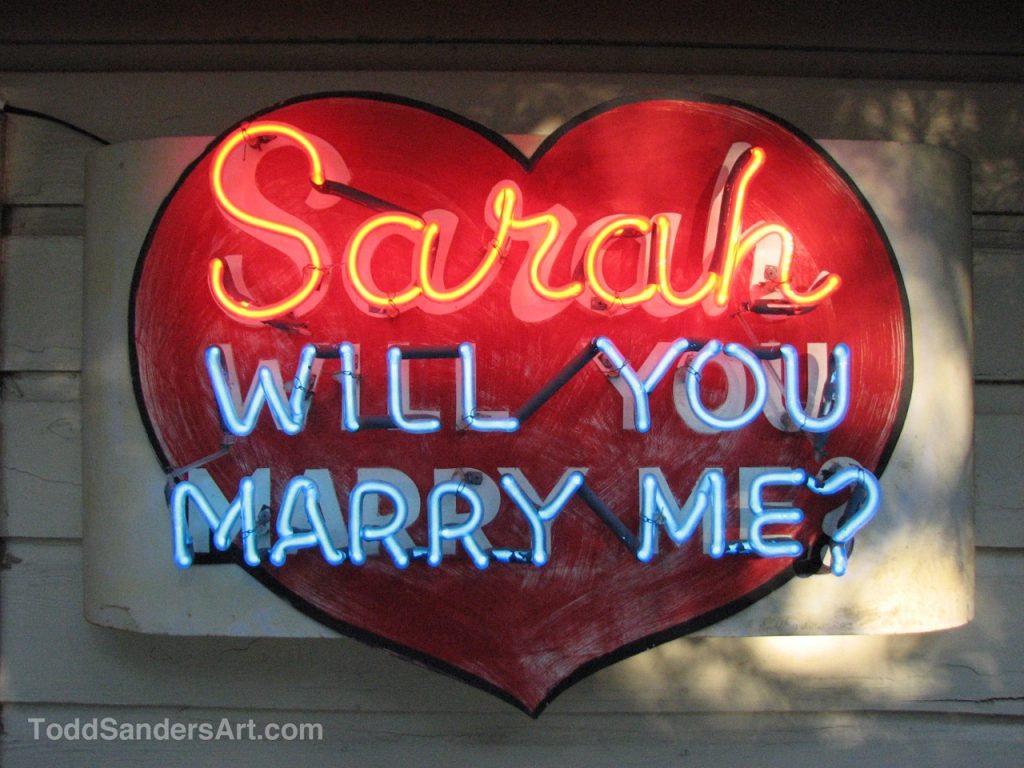

“Neon has never stopped being magical,” Sanders says. I’ve been travelling down a neon road my whole life.” Sanders even used it to propose to his wife. “It was a 3ft by 2ft heart that said, ‘Sarah, will you marry me?’ in red and blue; the natural colours of neon and argon.” He even faked a power outage to amplify the element of surprise. “This place [the studio] is like a discotheque at night, it’s completely lit up. But I’d turned it all off, and when I plugged in the extension cord I got down on both knees rather than just one. I had no idea how I was supposed to do it, but she said yes!” Todd, you old romantic.

Their son Jack, aged 13, appreciates his father’s heritage craft, but there’s no pressure for him to take responsibility for Sanders’ neon legacy. “I’m 56, and I want to keep doing this for as long as possible,” Sanders says. In 2022, he released a book, and recently he’s been experimenting with collage in the painted element of his pieces. “It’s getting harder to find old signage on the roads, but I’m making things that are going to be around a lot longer than I am.”

Conversation meanders to Sanders’ hat. “I wear it every day, it’s how people recognise me.” Distinguished by the cattleman crease in its crown, the design dates back to the late 1930s, when Route 66 was just over a decade old. Handmade and styled with “just a little bit of an upturn,” it’s known as a Stetson Open Road. “I only set it down when I’m at home,” Sanders says, but who knows when that’ll happen next. When the working week is done, freedom for Sanders and his family is a car full of gas and an empty highway ahead. Leaving everything that’s familiar in the rear view, together, they go looking for neon on the horizon.