His office is the front end of a Boeing 737, his mantra is “if it doesn’t exist, build it”, and he recently ate a bowl of spaghetti bolognese off the wing of a U-2 spy plane when pulling a late shift in the workshop where he repurposes old aeroplane parts, but aviation upcycler and engineer Stu Abbott downplays how remarkable his everyday is: “I’m just a guy in Durham making stuff.”

That “stuff” has included an office desk fabricated from an airliner emergency exit door; a dining table sculpted to show off the camber of the mirror-polished CFM56-3 engine intake nose cowl that forms its base; VIP pods for an aviation-themed gin bar built out of sections of fuselage and seating salvaged from ex-Germania 737-700 and Qatar A340-600 aircraft; a 3.5m x 4m wide bookcase constructed from galley carts which would normally be used for dispensing drinks, nibbles and duty free; and an extravagant cylindrical summerhouse made out of a 26ft long, 1.5 tonne passenger jet cockpit that featured on George Clarke’s Amazing spaces. “The sky is the limit,” says Abbott. “The more custom, the more bonkers, the better.”

Upcycling “bits of aeroplane that were never designed to be what I want them to be” requires a particular and precise modus operandi. Cut up an aircraft incorrectly and it will collapse like a crisp packet, warns Abbott, whose passion for, and knowledge about, deconstructing, recycling and redesigning aircraft parts is founded by ten years of service in the RAF as a fighter squadron technician on the front line and a career servicing civilian aeroplanes.

He established Stu-Art Aviation, a one-man operation, as a side hustle in 2012 after turning an aeroplane seat – which are considered one of the hardest parts of an aircraft to dispose of safely due to the mixture of chemicals and materials used to make them fire retardant – into an office chair, and selling it on eBay for £150.

To account for the specific characteristics that each aircraft component has, Abbott over-engineers his designs with load bearing features such as steel frames and toughened glass to ensure structural integrity. Failure to do so could result in them being susceptible to fracture, deformation or fatigue in their reincarnated form.

“Once you start taking the bits of aeroplane apart you realise how thin and light they are. I can lift a two-metre section of overhead lockers with one hand and carry a three-metre long wing from a light aircraft on my own,” explains Abbott. “I have to get my head round the practicalities of each concept before I start building.” What people don’t see, he admits, is the tears of frustration when he’s struggling to get something to work: “It’s not easy, but it’s a process I thrive on and I always find a solution in the end.”

Constructing a 26-seater boardroom table with a six-metre, quarter-tonne chunk of wing that used to lift an Airbus, for example, presents a unique set of challenges. “A wing is designed to flex, when you take off and land you see them bouncing around because they’re designed to do that. To make this table I had to remove its skin, which accounts for about a third of the material that holds it together and gives it strength, because the client wanted to show off the framework inside it – which meant it wobbled like mad.”

Abbott’s solution was to apply similar engineering principles to that of bridge building. He created a solid steel frame, within which the wing – that had been cut into three separate pieces and bolted back together – could sit. This meant that any vibration or movement stopped at each join.

“My military background taught me that you do the job to the best of your ability and until that point is reached, it’s not good enough,” says Abbott. “With aviation the stakes are a lot higher so the tolerances are a lot finer and I apply that to what I’m doing now. Unless I’m 100% happy, nothing leaves my workshop, and I won’t rivet my Stu-Art Aviation name plate onto anything until it’s installed and the customer is happy. It’s the last thing I do.”

With access to aircraft breakers yards and a little black book of contacts who facilitate off-market deals, Abbott is confident that he can get hold of “pretty much anything, anywhere in the world” – but even with a surplus of decommissioned aircraft available due to the impact Covid-19 and the drive for a carbon-neutral future, haggling is still par for the course.

“Older and thirstier aircraft are expensive to run so are being scrapped in greater numbers. Companies that break down aircraft often scrap the frame and sell the parts for a premium to airlines for spares. I go along and find out what they’re not using,” says Abbott, who recently donated 500 in-flight meal trays to a local homeless shelter so that they no longer had to use disposable polystyrene ones to distribute meals. “I cut the whole section off a jumbo jet at Prestwick Airport in Scotland once, and with my aircraft background I know how things are made so I know how things come apart and how to strip them properly. I get offered stuff every single day.”

The evidence is stacked and stored on racking back at Stu-Art Aviation HQ. There’s pieces of Concorde, parts of a Spitfire, and the 7ft by 37ft wing section from an American U-2 spy plane, which he plans to turn into a table and auction off for charity – a project which is an exception to the rule that Abbott refuses to work with parts that have been salvaged from an aircraft involved in an accident that resulted in the injury, or loss of life, of those on board.

Abbott explains: “I like to know the history of the stuff I’m working with. This is the last remaining piece of the American U-2 spy plane that took off from RAF Fairford on a reconnaissance mission and stumbled across the mass war graves site in Srebrenica during the Bosnian war. Two weeks later, something went wrong during a landing and it kart wheeled off the end of the runway – the pilot died. I’m going to build a memorial table in his memory out of the slice I have, engrave it with his details, and auction it to raise funds for charity.”

Fixing Tornados under the cover of darkness in an active war zone, Abbott says, helped him to hone his tool skills, and when he left the Armed Forces the father-of-two expanded his range of expertise by teaching himself techniques such as welding and vinyl wrapping – the latter of which is carried out inside his 737 office-cum-paint shop, which fitted through the workshop door with just 3/4 inch clearance on either side.

“It’s still got the cockpit, kitchen area and toilet module, which I use as a store cupboard. It’s just an aeroplane in a workshop, in Durham,” says Abbott, who believes his double-height unit filled with extraordinary aviation artefacts is the perfect environment to inspire children who struggle to thrive in the mainstream educational system. “Everywhere you look, there’s something to look at. I work with a company to teach kids who struggle with anxiety or behaviour; they help me with projects and it shows them that they can do something positive.”

Prioritising quality over quantity is Abbott’s abiding maxim. “I’m not making rubbish to chase money, I build quality stuff, slower. I want to make sure people are getting good value for money, that’s a big thing for me. I could put extra zeros on but I’d rather people have things I make and enjoy them.” Wall clocks made from an aircraft window section fetch around £35, while a desktop business card holder crafted out of a seatbelt is around £40, and coffee tables, usually, start at around £130. Abbott adds: “I sold one recently for £2500 but it was expensive because it was a statement piece made out of an A380 prototype wheel that was worth £48,000.”

In his spare time, Abbott is doing up a Tornado fighter plane for a museum in Sunderland and plans to start documenting what he’s doing on YouTube. Confessing that he runs on adrenaline and Jaffa cakes “I can smash a packet in about three minutes, or chocolate hobnobs” Abbott says it’s his family that keeps him grounded: “It’s difficult not to sound arrogant when I talk about things I’ve made and done, but the main thing for me is being able to show my sons what their dad has achieved, and saying to them, imagine what you can do.”

Read more

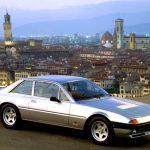

Restoring the world’s rarest Ferraris is all in a day’s work at Moto Technique

Hard Craft: Jim Tanner, cyclekart maker

Picture perfect: The former McLaren designer who drew a new life