After 14 years in Formula One, 10 years as a chief mechanic, 167 consecutive Grand Prix races and 668 pit stops, Alastair Gibson typed out his resignation. Disenchanted with a day job that’s one of the most pressurised but well paid and sought-after in motorsport, he hit send on the email without hesitation. Officially terminating his own employment to become an artist was one of the most “pleasing” moments of his F1 career, “because I did it on my terms.” It was time to sink or swim.

“I was tired,” explains Gibson, as he stares into the aluminium eyes of a 1.2m long Mako shark. Manufactured out of a pair fuel tank flap valve plugs, they are painted as black as the ocean’s abyss. “The passion was gone, I switched off to it completely, and if you haven’t got the passion you can’t do that job.” The race-to-race existence, which included stints with the Benetton and BAR Honda GP teams, combined with jet lag, politics and personal battles for supremacy (within and between race teams) had taken its toll.

“It was a real emotional drain spending all my effort and time making a beautiful race car that sometimes only lasted 5 laps before it got smashed off the track. I’d think it was such a waste of energy and enthusiasm,” says Gibson, a sixties child born in Johannesburg, South Africa. Leaving his hometown to pursue his dream of becoming a GP mechanic during the apartheid policy era had been difficult. “Having that passport wasn’t great,” but a humble attitude and a lot of graft got him “to where I was,” and by the late-noughties that wasn’t a good place. “I’d go to the check-in counter at an airport and not know where I was going. I’d be disoriented when the hotel alarm clock went off in the morning and then I’d go to the race track, stand in the garage and for a split second, and think: where am I?”

Fortunately, Gibson could see a life beyond rebuilding race cars; he wanted to sculpt sea creatures – from sharks to sturgeons – using carbon fibre and salvaged parts. “My father thought I’d lost my marbles,” he says. “My whole life had been motor racing, preparing a vehicle to do a certain job, to win, to be safe, and to achieve what those people above you wanted to achieve, but dumping that responsibility was like a breath of fresh air.”

A decade and a half later, with a studio in Northamptonshire that employs six (known as Carbon Art 45) and with pieces sold to F1 glitterati including Jenson Button and Rubens Barrichello, evidence suggests Gibson’s risk is reaping its rewards. The business often attracts clients that have such a high-profile that non-disclosure agreements need to be signed. “I was naive to what it would take to make a success of it, I put all my money that I saved into it and sold a couple of cars. I’ve worked harder than I worked in Formula One,” says Gibson. In the early days, the funds he raised building, designing and restoring motorbikes, including two Brough Superior land speed motorcycles for Jay Leno, helped keep his creative start-up afloat.

At the shallow end of the Carbon Art collection, a shark keyring or mackerel magnet, from £95, is an affordable way for a petrolhead to dip their toe, but venture deeper, and you can “get a bit groovy” for £585 with a red bellied baby piranha. Dressed in iconic seventies GP racing livery and suspended mid-air on a semi-flexible stainless steel stand, they make dinky but eye-catching decor, but so too does the 100g floating shark paperweight. The £185 piece has a base is made from a gear used by Sergio Perez during the 2016 season.

Each sculpture, which take months to develop, is available in three sizes (the biggest measures in at 3.5 metres) and all of them are produced to a limited run. Designs can also be given bespoke treatment but taking the plunge and investing in a larger, personalised, piece of work, will come with a five figure asking price. “The weird thing about it is if petrolheads have £15,000 to spare they’d rather buy another car or another engine for their car, so it tends to be art lovers that buy my pieces,” says Gibson. “If you buy a sculpture it’s got a lifetime guarantee. I’d hate to think one of my best pieces was in a loft because it’s got a piece of it broken off – bring it back and I’ll fix it.”

Nature and engineering, explains Gibson, are inextricably linked, and biomimicry, when a man-made product imitates nature to solve a design challenge, is a practice that’s widespread in automotive. Cooling vents that mimic fish gills to enable an engine to breathe is one such example, and when choosing the base material for his sculptures Gibson applied the same methodology. “My take on it is if god were designing them and he had free reign on materials he would have used carbon fibre because it’s light, it’s strong, it doesn’t rust, and it wouldn’t sink to the bottom of the salty ocean.” It also looks extraordinary when the light catches it.

“Carbon fibre in the sunshine is a religious experience, it’s beautiful, it’s mind blowing,” he says, succumbing to a moment of near rhapsody. Baring three layers of titanium teeth, a two-tone tinted blue and charcoal grey mako shark has caught his eye. Shimmering in the daylight and coated in a UV protective lacquer to prevent fading, the finish is an intentional nod to a shark’s natural colouring. “When you’re swimming underneath a shark and look up, it’s grey, but looking down on a shark, it’s blue.”

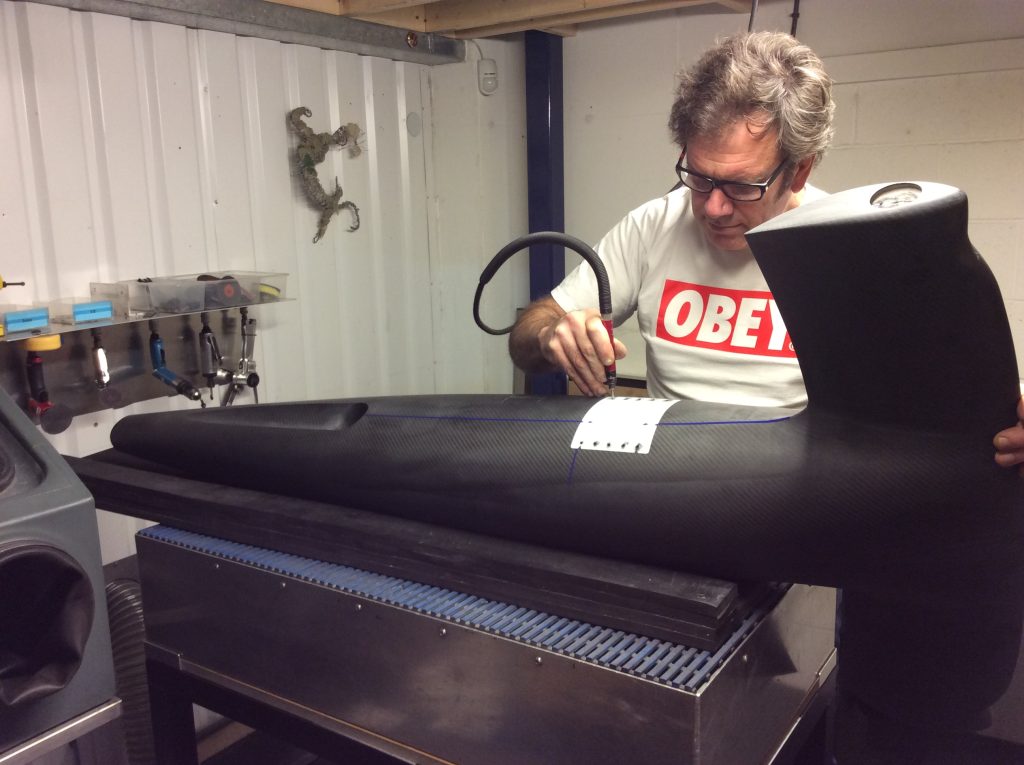

There are two distinctive sides to Carbon Art 45. Upstairs, which is a production line of finishing touches, and downstairs which is a powerhouse of hardware including a milling machine and lathe. There’s also “Margarita’s Dirty Room” with an extraction table where carbon fibre pieces are prepared using a blaster, grinding wheels and a sander for the more delicate elements.

It’s at Gibson’s workstation where sculptures start their life as wood carvings with a centre line that allows him to choose its “best” side. This half is 3D scanned and mirrored to create a perfectly symmetrical digital (CAD) version which forms the template for moulds and patterns. To decide which part of a GP car to incorporate into each piece, Gibson raids his Aladdin’s cave of reclaimed components that are sourced from teams including Red Bull, Williams and Aston Martin. “I’ve got another unit that’s just absolutely full of stuff,” he reveals. “The problem is I’ll spend a whole day there because I’ll look for one thing, find another, and another.”

Taking a flat sheet of carbon fibre, which looks and feels like a fragile sheet of nori (the dried seaweed that’s used to make sushi) but is actually five times stronger than steel, he manipulates it into the curve of a mould. Warm hands are a vital tool. “It’s a case of rubbing it to fit but you don’t want to stretch it too much because then it would look like a pair of laddered stockings.” Multiple layers are placed on top of each other, a process known as laminating, which enhances the structural integrity of each piece. “I learnt how to use carbon fibre in Formula One because we made a lot of our pit equipment out of it; water towers, car stands, that sort of thing. It was great because if you made a mistake, you chucked it in the bin, but it’s £40 a metre and we probably spend about £50,000 on it a year, so I don’t do that now!”

Impregnated with a resin that cures at room temperature, the carbon fibre has to be stored in a freezer at -20°C to prevent it from going hard prematurely. When it’s ready to be cooked it goes into an autoclave that increases in temperature at a rate of one degree per minute, up to 120°C, then reduces it back down again just as gradually to prevent stress. To guarantee each sculpture receives a top-notch paint job, Gibson ships them to the Mercedes Grand Prix team paint shop, which conveniently, is next door. “A lot of the really cool paint jobs we’ve done in the past are thanks to them being able to experiment.”

If it hadn’t been for his late father, who imported vehicles into SA for Porsche Motorsport, “I would probably have been a marine biologist,” says Alastair, whose obsessions with automotive as well as what lives beneath the waves can be traced back to when he was a boy. During the South African motorsport season Alastair would help his dad prepare and test cars for events such as the Springbok Championship Series and spent time in the company of “big characters” such as Peter Sutcliffe.

“I’d come home from school and there would be beautiful 904 and 906 Carreras in the garage. We’d take them out to this open road and I was blown away by the technology.” Off-season Gibson and his parents vacationed in a holiday cottage, “Fisherman’s Rest”, on the coast. “My dad and I weren’t fishermen but we loved going down to the beach to see what local fishermen had brought up from the surf. Invariably they caught sharks, but this was the mid-70s and no one gave a s**t about the planet, so they used to drag them onto the beach and leave them to die. They were seen as vermin in the ocean. I used to grab their dorsal fin, put them in the shallows and walk them round for a bit – some of them fired up again!”

Today, Gibson is a proud patron for the Shark Trust and finds himself humbled by the aspirant artists that come to Carbon Art 45 for work experience. “The world is a difficult place so it’s amazing when someone finds their thing,” concludes Gibson, who was brave enough to swim free from the F1 fishbowl to find his happiness.

Read more

Hard Craft: Fine tuning with The Vintage Wireless Company

Tiny treasures in Amsterdam: meet the maker creating wearable classic cars

How one man’s scrap becomes another man’s sculpture: The nuts and bolts of upcycling with metallurgist Mario Tagliavini

I have one of Alastair’s smaller pieces and aspire to owning one of the larger ones. I love the juxtaposition of motorsport and the marine world.