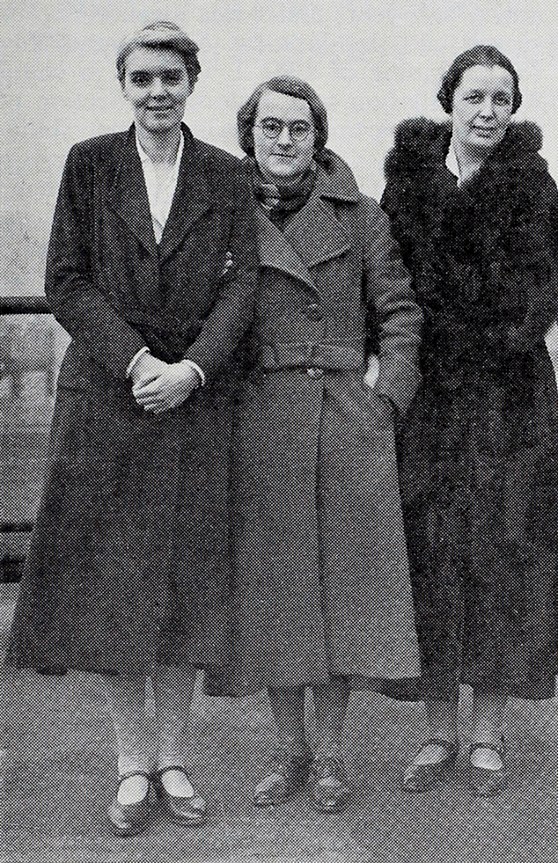

Two decades before Katherine Johnson, Mary Jackson, and Dorothy Vaughan broke through racial and sexual bias to make history at NASA in the 1960s – a feat celebrated in the 2016 movie Hidden Figures – there was Beatrice Shilling.

Shilling, known as Tilly to her friends, was a remarkably gifted British engineer who in 1936 was recruited to serve as a scientific officer in the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE), a position she held until her retirement in 1969. Shilling’s decision to join the RAE had a lasting effect not only on her life but also may have saved the lives of pilots and soldiers in World War II.

At 14, Shilling was an inquisitive teenager who bought a motorbike, with which she was constantly tinkering. She wasn’t dreaming of becoming an engineer at the time, but that all changed when her mother discovered The Women’s Engineering Society. Inspired, she secured her daughter an apprenticeship at an electrical firm and, in 1932, Beatrice earned an engineering degree from Manchester University. In doing so she became one of the first two women to study engineering at that institution. With jobs scarce during the Great Depression, she went on to earn a master’s degree, focusing her research on combustion engines.

Shilling wasn’t just mechanically inclined, either; she also became a proficient motorcycle racer in the 1930s, lapping Brooklands at 106 mph on her Norton M30 500 to earn a gold star. She also raced four-wheeled machines, driving a 1935 Lagonda at Silverstone and later racing sports cars at Goodwood in the 1950s.

In a 1969 letter, Shilling recalled her arrival at the RAE in 1936. According to northropgrumman.com, Shilling wrote, “The Air Ministry, having had some experience of women’s work in the First World War, were not entirely unsympathetic, and I was offered a job as an assistant in the Technical Publications Department at the Establishment.” After spending eight months writing aero-engine handbooks, she was transferred to the engine department, where she specialised in research and development on carburettors, a much better match for her skills and interest.

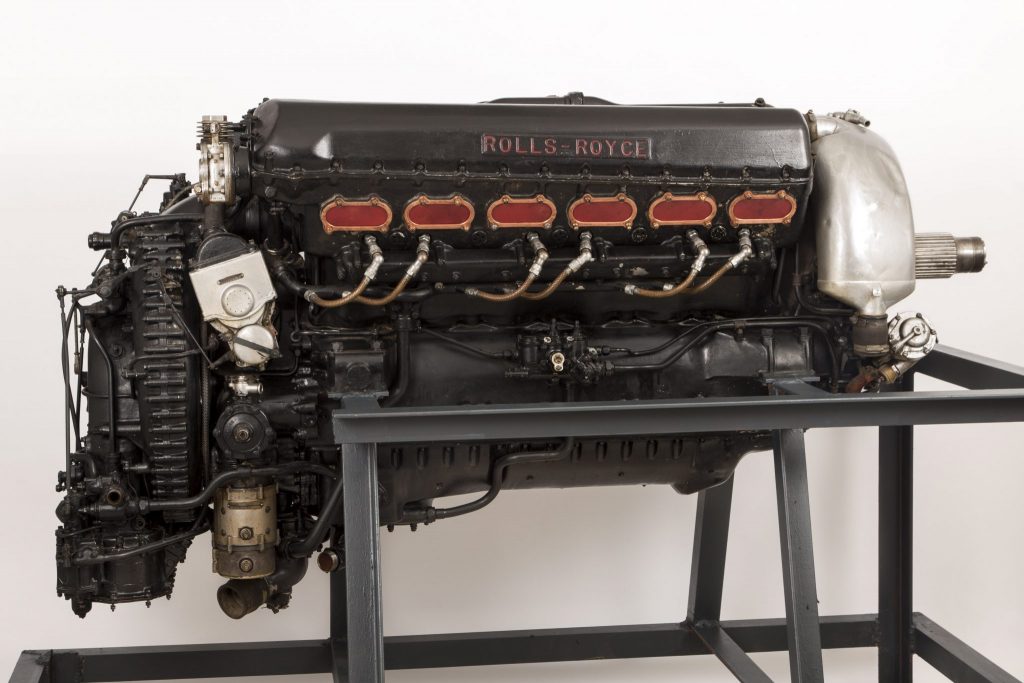

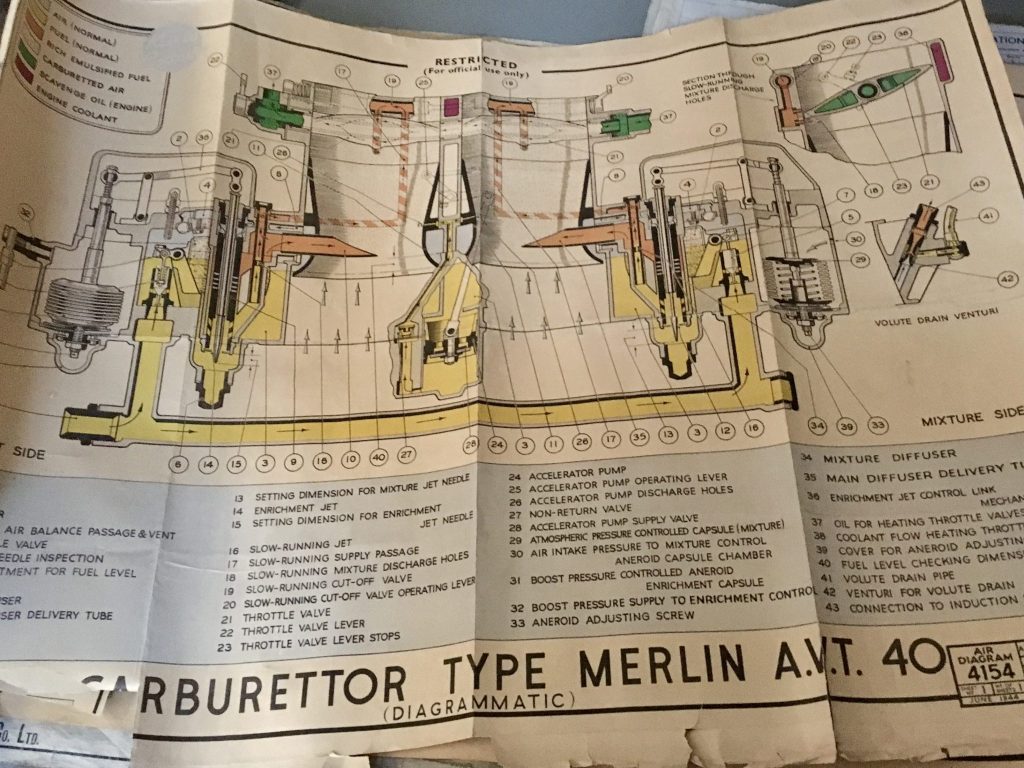

In 1940, the 31-year-old Shilling found a solution to a carburettor malfunction in the Rolls-Royce Merlin III engines that were used in Royal Air Force Hurricane and Spitfire fighter planes. Employing 100-octane fuel to increase boost and increase engine output to 1310 horsepower, the planes were fast enough, but the Merlin’s Skinners Union (SU) AVT35/135 carburettor would suffer a “fluff” when entering a steep dive. The negative g-forces would momentarily throw the fuel to the top of the float chamber and starve the jet of fuel for 1.5 seconds. Although the carburettors would regain function, the situation was potentially disastrous. Shilling devised a preventative modification, retrofitted to all serving aircraft: a restrictor (or orifice plate) with a calibrated aperture in the centre was fitted to the fuel line before the carburettor. It limited the fuel flow to a volume only slightly less than the engine demanded at full power, and while it did not stop the momentary weak hesitation, it prevented the excruciatingly long 1.5-second cut.

By 1941, the Royal Aircraft Establishment had developed an anti-g modification which would become a standard feature of all new SU carburetors. However, Miss Shilling’s restrictor was retained by many aircraft, depending on their role in battle.

“Beatrice Shilling is an inspiration to us all,” says Mark Burnett, managing director for Burlen Limited, which still manufactures and supplies SU carburettors around the world. “Not only was she a first-class engineer but she also loved speed and was fast on both two wheels and four.

“Miss Shilling should be celebrated and remembered for the incredible woman she was, and as an engineer who made wartime pilots lives as safe as they could be when in battle.”

Eighty years later – and 30 years after her death in 1990 – we salute Beatrice Shilling, whose inquisitive mind and quest for speed and adventure broke the mould. Her contributions to the Allied Forces in World War II are a testament to her lasting legacy.

Via Hagerty US

Interesting article

Does it just no do to mention that the device was universally known as Miss Shilling’s Orifice?

Pity…

Miss Shilling was still at RAE Farnborough when I was an apprentice there. It is nice to see her story being told to a wider audience.

Richard Brown

Great article, not heard about her before. Unfortunately there is always one comment to lower the tone.

In the wider context during the Battle of Britain the Daimler Benz engines of the German Me 109s had fuel injection so had no problems with zero gravity. wonder why Rolls Royce never adopted it?