“I hope I’m not scaring you,” Jaime Kopchinski says to the photographer and me. We’re passengers in his 1959 Mercedes-Benz 219, driving past the old churches and barns that surround his shop. I never saw the speedometer go far past 40mph, but that indeed felt fast for a car with a radio made of tubes.

A few minutes in, though, I started to adopt the confidence Kopchinski had in his Mercedes. It wasn’t rolling hard through turns. Nothing groaned. The seats didn’t bounce or vibrate. It held the road and absorbed bumps well (an important attribute in postwar Germany).

The drive demonstrated a point that Kopchinski had made earlier about vintage Mercedes-Benzes: “These cars are designed to be extremely robust. It can run sustained at 5000 or even 6000rpm all day until you run out of gas.” A Mercedes such as this, like the ones he works on, were built for real driving, in modern traffic. His job is to get them back to that factory setting.

You wouldn’t think much of Kopchinski’s place, Classic Workshop, if you drove past it. Just a nondescript New Jersey warehouse some 50 miles west of Manhattan. Yet it’s notable for a number of reasons. For one, it’s bursting with youth. If you need confirmation that the classic car world is full of young, curious, capable geeks, here is a good place to look. Kopchinski is only 44. He’s got a beard, flattering eyeglasses frames, and works in a black T-shirt with the shop’s logo – a minimalist outline of a thin vintage Mercedes steering wheel, designed by a friend who worked in fashion marketing.

He has two employees: Alexander Potrohosh came from Ukraine with his wife and 2-year-old son as refugees. Aside from his mechanic skills, Kopchinski says Potrohosh has a special touch with dent removal. Veronica Petriella is a recent graduate of Universal Technical Institute and drives an ’87 300SDL. She’s also transgender, which is only worth mentioning because she exemplifies Kopchinski’s mission of hiring techs with a wide spectrum of backgrounds. “At the moment, we don’t have any techs from the traditional dealer or repair shop world,” he says. “That’s quite intentional.”

Then there’s the simple fact that this shop exists at all. The pandemic made the already tough business of automotive restoration even more challenging. With the cost of parts on the rise and skilled labor on the decline, even some veteran restorers have decided to call it quits. Yet for Kopchinski, it’s the realization of a long-held dream.

Despite his young age, he already has a decades-long list of accomplishments in the automotive industry which informs how the place operates. Before he opened Classic Workshop in March 2023, Kopchinski worked in-house at Jaguar Land Rover, managing a team of engineers tasked with optimizing the infotainment systems in models like the 2020 Defender. And before Jaguar Land Rover, starting in the early 2000s, he worked on the radios and infotainment systems in Mercedes-Benzes. You can find his work in the AMG GT, the E-Class, the S-Class, and Maybachs of the 2000s and 2010s.

In 2017, when Mercedes relocated his department from New Jersey to Southern California, Kopchinski reluctantly quit, took the severance pay, and spent the next several months wrenching on cars in his home garage. “That was probably the first taste I had of actually working on cars all time,” he says. “It was the best.” Five years later, when he was at Jaguar Land Rover, word-of-mouth referrals led to a waiting list of over 30 cars. Meanwhile, the pandemic spiked the value of the vehicles he was working on. He started asking around about which buildings were available and applying for loans. Wherever he went to make his case to get the operation off the ground, he arrived in a vintage Mercedes-Benz, usually a 1972 280SE, as a conversation starter for the business.

Kopchinski found his building, secured loans, and convinced the town council to let him open his business. After he had set up successors and delegated projects, he told Jaguar Land Rover that 10 March, 2023, would be his last day. “Every one of my colleagues wanted to know about the business,” he says. “Because they’re car people. They were so excited about someone going into their passion.”

That background gives him a unique perspective: Although he’s obviously obsessed with old cars, he is not one to romanticize the past and dismiss the automotive present. Kopchinski can wax poetic about the latest generations of the S-Class. He recalls test driving one in Florida, along the Tamiami trail. “There’s this dirt road that runs parallel to half of it,” he says. “We were going 40 miles an hour in a prototype S-Class, just flying down the road, rushing through puddles, slowing down for the alligators. They’re just so robust.”

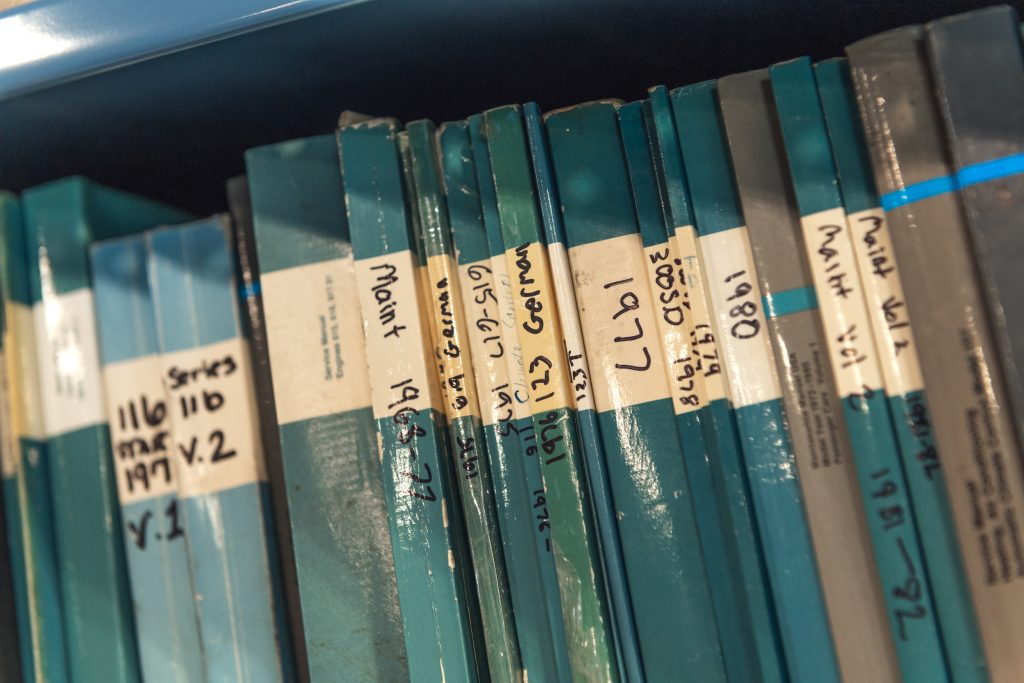

His past life may also inform his appreciation for what he calls “The real treasures in this place.” On a shelf behind one of the workbenches, underneath a tool for diagnosing Bosch fuel injection systems, there are dozens of small books. They’re full of diagrams and specifications – torque for certain bolts, power output curves, something called ‘injection timing device bushings.’ “It’s every technical spec that you could ever imagine,” Kopchinski says.

The shop itself is huge, bright – it’s such a big space that you don’t really have to hunch over or watch where you’re stepping. Inside are two lifts, workbenches, organized shelves full of parts and tools, a wheel balancer, a forklift, and a bunch of customer vehicles – an R129 SL-Class, a W126 S-Class, a G-Wagen, stuff from postwar all the way through the ’90s. The walls have big plastic Mercedes-Benz star logos and posters that he rescued from the trash, at his old job.

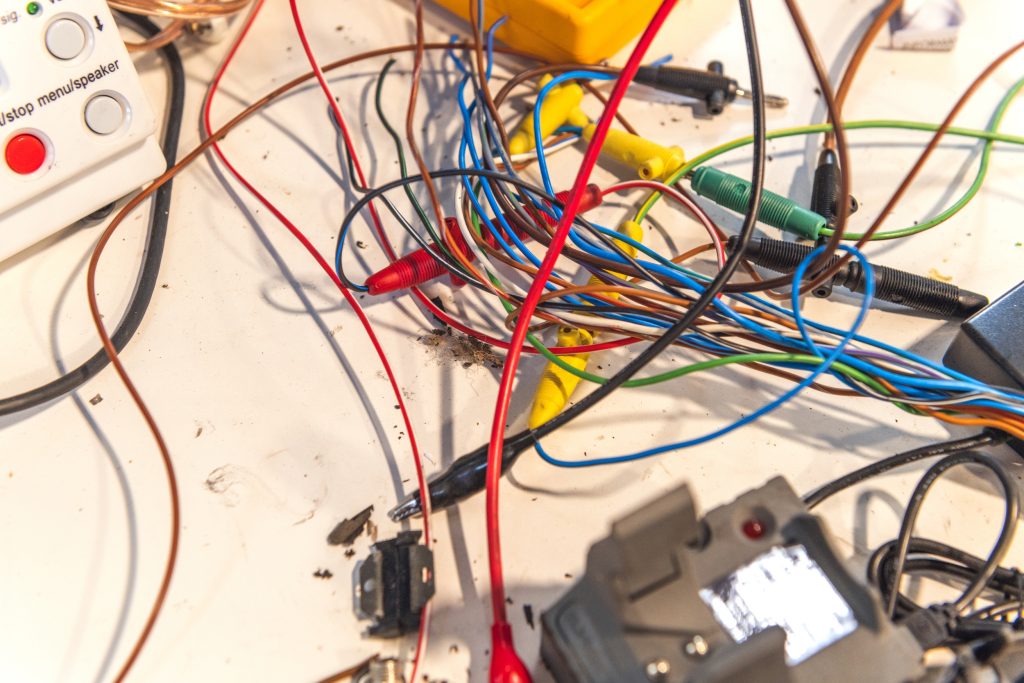

The shop is busy, too, with 15 to 20 vehicles being serviced on any day and a waitlist of around 35. The work surfaces reflect this, with Post-Its and grime-covered parts. But the space is so clean and organized that you’d think it serviced electric vehicles. The only blemish on the surgically clean, light grey floor is some fluids that spilled from an old SL.

Along with the manufacturer’s obsessive documentation and a range of specialty tools, Classic Workshop’s operation depends on a reliable flow of quality parts. Which, Kopchinski says, Mercedes does especially well. “A lot of people like to complain that Mercedes doesn’t support their classic cars,” he says. “But I find that to be untrue.” He gets daily FedEx deliveries from Mercedes-Benz Classic Center in Long Beach, California, which supplies the majority of the parts that he uses to get and keep cars running. “Pretty much anything I could need, they can get me tomorrow morning,” Kopchinski says. For components that he can’t get straight from the source, he orders them from separate supplies, which Mercedes will often hire to keep up with demand. These replacements might cost more than and look a bit different from the originals, but the metal and rubber will be the same as what was put in the vehicle at the factory.

Part of what makes sourcing so easy for him is that, as he observed while working there, Mercedes thinks hard before making any changes to their cars. Both an early 1970s S-Class and a 2015 S-Class, Kopchinski points out, have the wiper and headlight controls in the same place. Another example: a connector that he pulls from under the hood of a 1991 420SEL, which is almost identical to the same corrosion-resistant, expensive connector in modern Mercedes-Benzes.

“I’m sure these engineers knew more than we do right now about that particular component. Mechanics love to say, ‘Why did the engineers do this?’” Kopchinski says. “But there’s a million reasons why they engineered a thing a certain way, and it’s not to screw a mechanic 15 years later.”

I ask him what these modern, gadget-laden models will mean for his shop and for people who want to buy an older Mercedes. The current models are loaded with transistors, sensors, and screens, tech hardware that were used to failing or becoming obsolete within a decade. Will touchscreen-operated scent diffusers be repairable?

Back when Kopchinski was working on the 2003 E-Class, he had the same thought – that they’ll be too complicated to fix, that they’ll only last 15 years. “Now, 20 years later, they’re great used cars,” he says. “And they’re maintainable, because everyone figured out the electronics.” That’s because this era of auto technology coincided with the growth of the internet, which made it easier to buy and learn how to use modern tools to install replacement parts. “Young people who are buying the 20-year-old Mercedes for their first $5000 (£4000) car, they grew up in the 2000s,” he says. “Electronics don’t scare them at all.” Kopchinski refers me back to his point about the caliber of work that he saw done at Mercedes: “[The engineers] take quality extremely seriously. [The cars] are just different. And that’s okay.”

Now, a skeptical reader might note that were it not for those electronics, modern Mercedes wouldn’t depreciate to $5000 in the first place. Yet part of what makes Kopchinski so good at making you want a classic Mercedes is that he sounds like he’s never stopped being a fan. By his estimation he’s owned between 75 and 100 of them. Most were ancestors to the cars he was helping engineer through the 2000s and 2010s. (He’s also owned two Porsches, two Saabs, a Volvo, and currently owns an NSU Ro 80—a West German sedan with a Wankel engine.)

Listen to Kopchinski for long enough and it becomes tough to be cynical about modern cars. The screens and driver aids in modern S-Classes seem less like excess gadgetry and more like timestamp advancements that mark the evolution of a brand. His shop, then, keeps examples of the markers in that timeline in motion, all keeping pace with each other on the road.

We go back to his shelf of Mercedes-issued technical books. In the copies dating from the late ’50s and early ’60s, many pages are dedicated to a then-radical technology: fuel injection.