Hello there! My name is Adrian Clarke. I am a professional car designer, earning a degree in automotive design from Coventry University and a Masters in Vehicle Design from the Royal College of Art in London. While I was there, one of my tutors was J Mays. (He used to bring in doughnuts.) I worked for several years at a major European OEM before the pandemic knocked the world into a cocked hat. In a previous life, in the Nineties, I daily drove a 1979 Ford Thunderbird while living in London.

You’ve just bought some flat-pack furniture. You begin to assemble it, only find some parts keep changing shape, and some parts are missing so you have to use leftover parts from an older, completely different unit. Overnight, while the furniture is sitting half-assembled in your garage, your neighbour comes around and helpfully rebuilds it for you without your knowledge, in a way that you don’t like.

Welcome to Design Realisation.

Design Realisation (sometimes called Production Design) is the second half of the car design process after Creative (or Advanced) Design. It takes probably three times as long as the first half, which means if the creative portion goes well it takes about a year. Realisation takes about three years (and in the case of troublesome designs can take longer). Essentially, it’s how a carefully crafted design vision goes from idealised desire into functioning reality.

After coming up with their design, the creative designer effectively becomes the aesthetic manager of the car. It’s up to them to make sure the design is not compromised (or altered as little as possible) as it moves towards production. They take the place of the customer and decide whether a part appears acceptable or not. Many more people from outside the studio will get involved, so there’s a lot more cooks to ruin the dish.

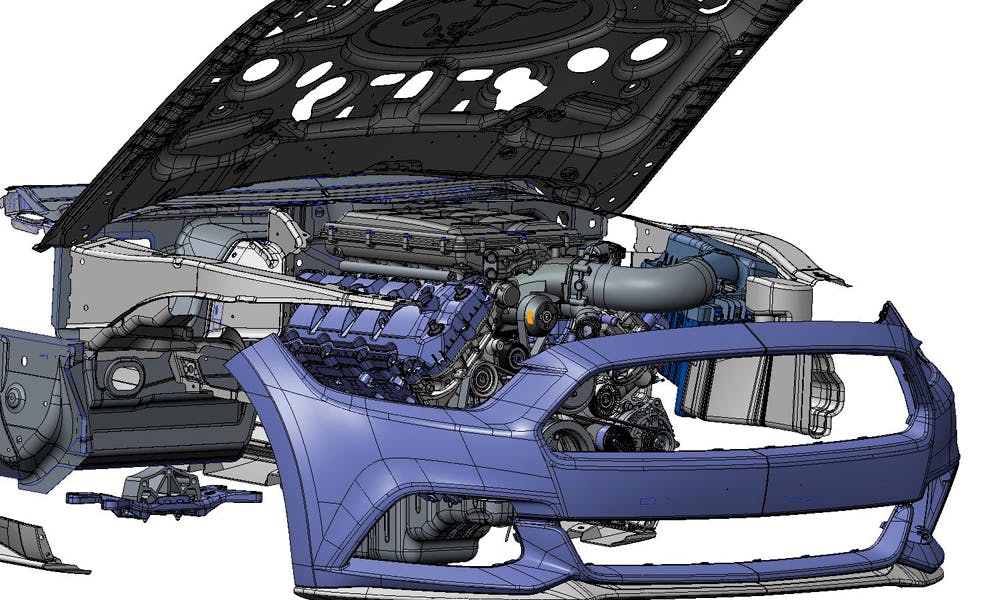

Some parts will be “carry over”; i.e. shared with an existing model or a sister model being developed at the same time. When operating on margins of less than 10 percent, this is crucial. It costs tens of thousands of pounds just to tool up for a small plastic fitting, so anything that has already been used elsewhere saves a lot of cost and development time.

A car I worked on shared its rear reflector/fog/marker light with one of our sister brand’s cars, which was a year ahead in development. So we had to make work a part that had been optimised for a completely different type and shape of vehicle. Talk about putting a square reflector in a round hole!

A lot of pain was endured tweaking the “A surface” (everything the customer can see or touch, as explained here) around the lower rear bumper area to ensure we remained legal for brightness and viewing angles and remain true to the design intent. It’s not just visible parts – maybe it’s a fuel filler bowl that doesn’t fit your curvy A surface because it’s made for a flatter panel. Tough luck – you have to make it work because there isn’t the time or the money to develop a new part.

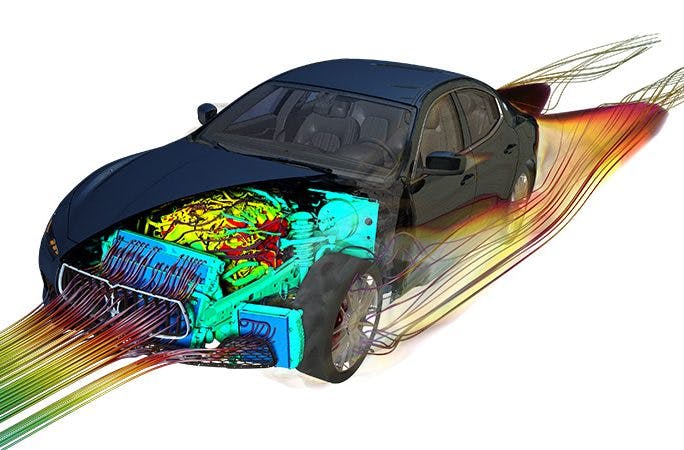

Plastic trim pieces that were 3D printed on the model need to be remodelled to incorporate a draft angle to allow them to be released from the injection moulding machine. How much draft will depend on how deep it is and how textured the surface. The mounting brackets might produce visible sink marks on the A surface; does more material need to be added to stop this happening? Now you’ve added more material, but is it too stiff to pass crash regulations? Every time you change something, it has a ripple effect somewhere else. It’s like trying to nail jelly to a constantly moving ceiling.

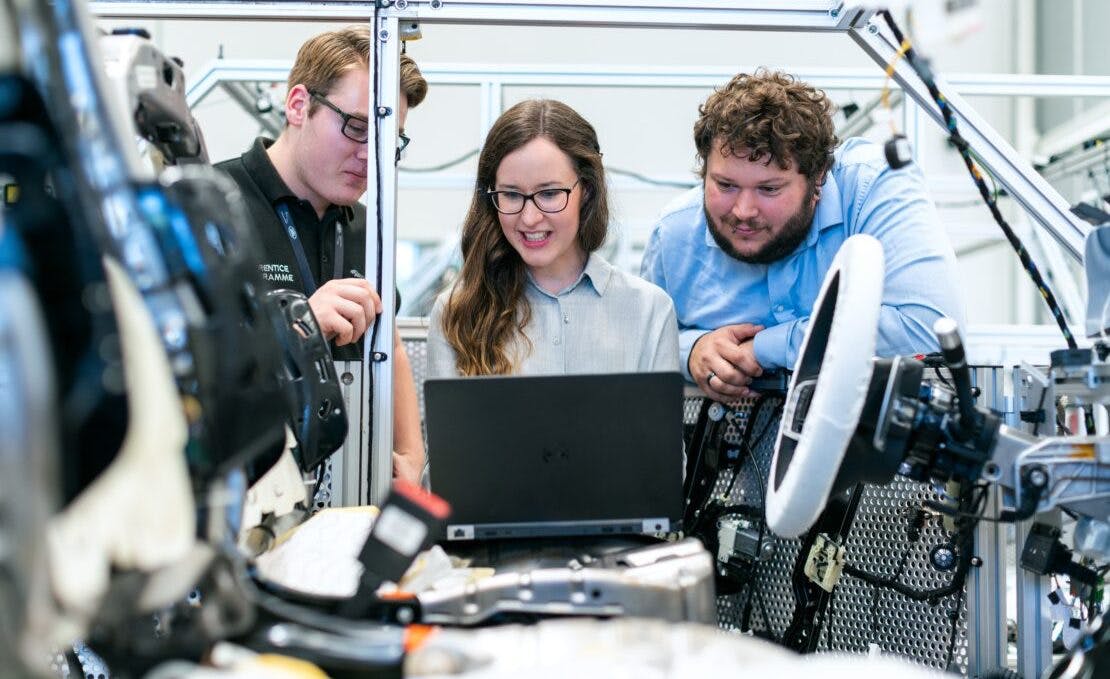

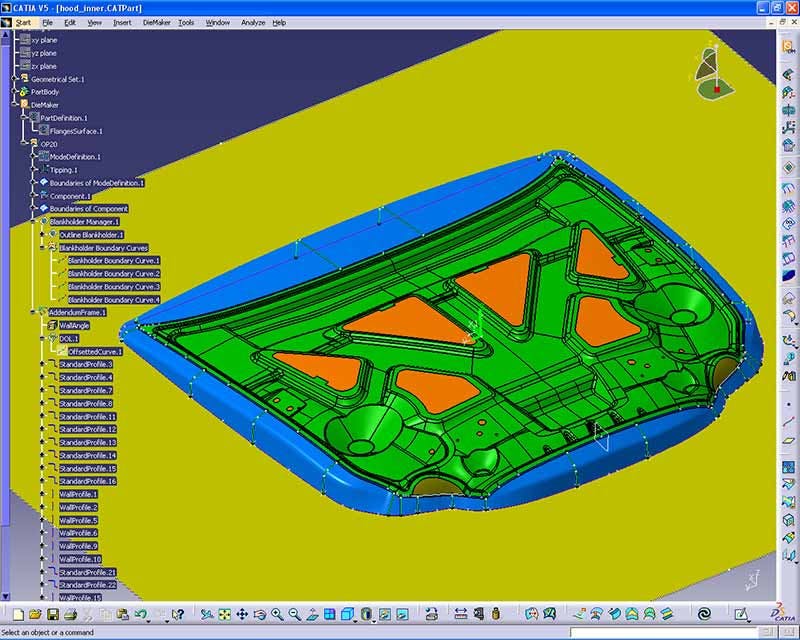

Engineering teams and module leaders look after the systems that make up the car. They will be the designers’ main point of contact and regular meetings and reviews will take place as parts are developed and jiggled into place. This is done digitally in an engineering program like Catia V5, where they have access to a digital “buck” of the car. (It’s worth noting at this point anything related to the exterior design of the car is kept on a separate server only accessible to those inside the design studio – otherwise you’re in for a leak.)

Marketing and Product managers decide on trim levels and powertrains, and how the car will measure up to or beat its competitors in terms of features and content. If you’re upset the car you want doesn’t come with the features you want, it’s not the designers’ fault. When you’re on the razor’s edge of profitability, adding something that has a cost of £500 doesn’t necessarily add that value to the car – it can subtract that amount in profit, multiplied.

A car I worked on had its retractable rear spoiler removed because it saved money and the same aero result could be obtained by adding a small fixed strip across the tailgate. Not only was this done on cost grounds, it was justified because a competitor had initially offered it on one of their cars and then replaced it with a fixed unit.

Manufacturing managers concern themselves with how easy and quick a car design will be to build. They would love it if a car was only available in one colour and one trim level; it would really shrink the cycle time. Foolproof repeatability is their mantra. Visually similar parts may need a poka-yoke on the B surface to ensure only the correct part can be fitted.

Likewise the palette of a car is determined by the number of colours the spray booths can handle. The reason premium German manufacturers charge so much for eye searing paint jobs is those cars must come off the line and be painted elsewhere, before being cycled back onto the line.

Line complexity is one of the reasons optional equipment is not available a la carte; the possible combinations would be impossible to manage with any degree of quality control (we couldn’t even do black wheel nuts – they had to be a dealer fit). If you’ve ever removed a door card and subsequently broke the clips holding it on, it’s because they’re meant to be quickly pressed into place by hand on the line – quicker, more repeatable and simpler than using tools.

The sheet metal will be subjected to Finite Element Analysis many times over before a single tool is cut. (These, after the lights, are the most expensive parts to tool up for. You want to get it right.) Will they stamp to an acceptable quality many thousands of times over? Can it hold its shape? The bottom of the A-pillar is a notoriously tricky area to get right; the A-pillar, fender, door and hood all come together in one place. You don’t want a visible rat hole where they meet.

When the light hits the paint you want smooth and consistent reflections – ideally you shouldn’t notice the shut lines at all. Where the fenders meet the bumpers is another banana skin. Bumpers are made from plastic and moulded not pressed, so they have a different surface quality and hold different radii; careful gap management and surface control can avoid the appearance of a paint mismatch.

Surface Reference Models and Tooling Reference Models (sometimes known as Function and Feasibility Cubes) allow for final checking of highlights, intersections, and panel gaps before being going to tooling. The lead time required is considerable, so the Body in White is one of the first things to be signed off – another reason changing the A surface for packaging reasons is not a solution!

Although car design might seem like a dream job for an enthusiast, it takes place within The Big Corporate Environment and is subject to the same political machinations and Machiavellian manoeuvring as any other large company. Engineers think logically and practically, so aesthetic considerations are not in their job description or ordinarily within their skillset. Project managers are under enormous time and financial pressure to deliver, so both these groups sometimes consider the designers (the felt-tip fairies or flower arrangers) to be superfluous or even a hindrance to delivering a car on time and on budget.

Dealing with this is what it means to be a designer, rather than being a mere stylist. Tasked with the delivering the frunk area of a car, I ended up banging heads repeatedly because the engineers thought it acceptable to run a $1 strip of self-adhesive 1-inch foam across a trim panel at the trailing edge of the hood for aero sealing.

From their point of view it worked and was cost effective. But can you imagine opening the frunk of your hundred-grand electric car and seeing that? The alternative was adding a vertical surface to a trim panel and using a press-on rubber seal, which would have added a couple of quid and a few days altering a part in CAD. Details are not the details – they are the design, as Charles Eames said. Despite review meetings taking place for which I was conveniently left off the invite list, I won that round.

As the car heads towards launch, the designer is still involved in checking the quality of pre-production parts and making sure the fit and finish of pilot build cars is as it should be. They may even need to redesign parts at the last minute. I once had to hastily redo the radio aerial in the rear side glass of a car when road testing revealed the AM reception was rubbish.

Pilot builds allow for manufacturing procedures to be worked out and making sure it all fits together properly. These cars will be used as the development mules, and the designer will come up with the camouflage used to hide the appearance of the design as it heads out on public roads. This was one of my first jobs, and I wanted to dress our car to make it look like a famous competitor vehicle (replicating their grille shape). That took some justifying, and the answer from the studio head after he had a good laugh was a resounding “no,” but if you can’t keep your sense of humour through all this you’ll never make it inside a design studio.

And if you want to make it inside a design studio, next time we will look at how you get to be a car designer.

This article, part of a series on car design, was originally published by Hagerty US.

Read more

From 2D design to 3D clay: Our industry insider peels back the studio curtain

Syd Mead’s Sentinel II thrills and excites now as it did in 1987

How not to build a car, Part 1: Bodywork