Hello there! My name is Adrian Clarke. I am a professional car designer, earning a degree in automotive design from Coventry University and a Masters in Vehicle Design from the Royal College of Art in London. While I was there, one of my tutors was J Mays. (He used to bring in doughnuts.) I worked for several years at a major European OEM before the pandemic knocked the world into a cocked hat. In a previous life, in the Nineties, I daily drove a 1979 Ford Thunderbird while living in London. Now I drive a Ferrari Mondial QV.

Harley Earl is widely considered to be the father of modern car design. By all accounts a well-lubricated, towering tyrant of a man, he didn’t invent the discipline (early coach builders had a small design staff of artists and fashion designers), but he nonetheless created the first design department at major corporate scale. He also organised and codified the studio system and created many of the roles that more or less are still used today.

So while tools may have changed, the processes remain broadly the same. And with that in mind, let’s take a look at the people that work inside the hallowed sanctum of a modern automotive design studio.

The creative designer’s primary responsibility is for the vehicle’s appearance, from conception to final form. Almost everything the customer can see or touch is called the “A” surface. Things like brackets, fittings, hinges and the grubby bits underneath are known as the “B” surfaces. Everything outside of the door seals is the responsibility of exterior design; everything inside of the door seals falls under interior design.

Underbonnet, door and boot shut faces are known as “grey zones”, and there will sometimes be an exterior designer who specialises in these areas. Likewise with lighting (front and rear), there will usually be a specialist who concentrates solely on light graphics, lighting technology, start up lighting animations and so on.

Creative designers usually have an array of model cars on their desks and play fantasy garage quite a lot. One of my managers (an Italian) found me looking at adverts for the Alfa Romeo Giulia Sprint GT and proceeded to explain to me in great detail the difference between a step nose, a Veloce and a Junior.

Alongside the interior and exterior designers are the Colour, Materials and Finish (CMF) Team, usually comprised of fashion, textiles and materials graduates. They work out the main colour palette for the car (initial models are usually coloured neutral silver; as the design progresses a “hero” colour will normally emerge showing the design in its best light), as well as the plastics, metals and textiles used on every “A” surface part of the car, from seat fabrics, interior trim, exterior details, right down to the pattern on the speaker grilles. The grain on the door bins or the knurling on the heater knobs? It’s all specified down to a technical level by the CMF team.

CMF also creates an ever-evolving and tediously long document called a “trim walk.” This document calls out every “A” surface part and what colour it comes in, its composition, and its pattern. This covers everything from the bog-standard base model to the top-level version. Once a design is finalised, moves into the realisation phase and its inexorable march towards production (we’ll cover this in a later article) it’s up to the designer to ensure the integrity of the design is respected, and not fouled up by the different engineering teams trying to save money and make their lives easier.

I can’t tell you the number of meetings I’ve sat in where the engineer’s solution to a packaging problem or a sensor issue or some such was to “just change the A surface!” Except you can’t because the design has been signed off and that part has already gone to tooling, so if you want to tell the studio head that’s your solution, be my guest. Just be prepared for the hair dryer treatment.

It may be an apocryphal story, but near the beginning of his GM career, when Harley Earl passed the design of the 1929 Buick to body engineering and production teams, they altered his design to such an extent (allegedly to make the body sides easier to press) that the resulting belt line bulge led to the car being dubbed “the pregnant Buick” by Walter Chrysler. To ensure such a thing never happened again, Earl brought his own engineers into the studio, and the role of the Studio Engineer was born.

The Studio Engineer’s role is to provide engineering support to the designers throughout the creative and realisation parts of design, and provide a link to the various engineering teams outside of the studio (i.e. the people creating and testing the parts and systems that make up the car).

Need to work out how the door swing angles are going to impact your shut lines? If the feasibility report from the wheel supplier is going to affect your carefully crafted alloy wheel pattern? The aero impact of altering that front vent? These are the people who say “yes that’s possible”, “no, that’ll never work”, or more likely “there’s not the money in the program for that”. As packaging, platform and hard points are nailed down, they will aid the designers in making sure the design fits all new requirements.

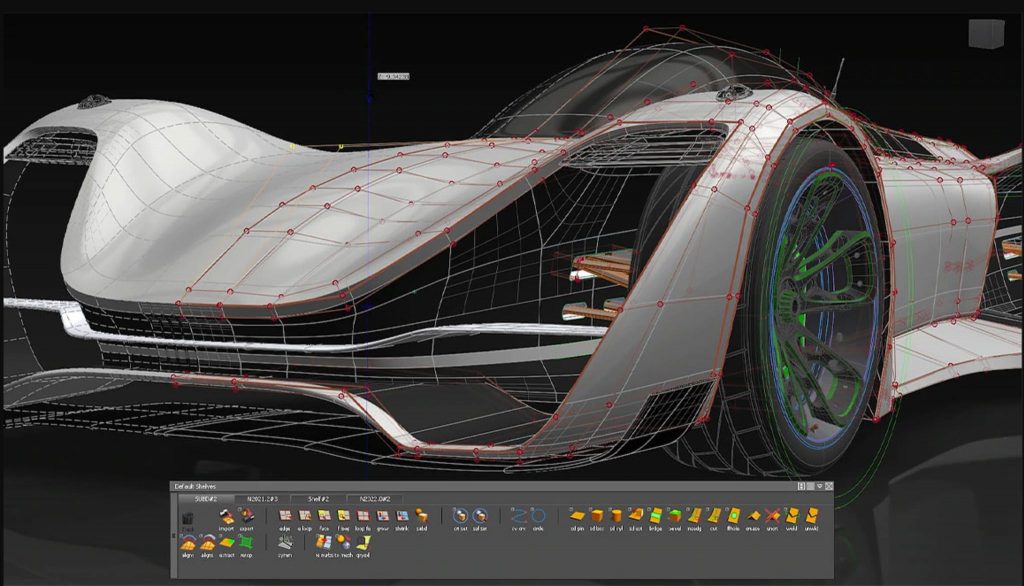

We mentioned modellers in the previous article, and CAD modellers usually work in Autodesk Alias. Alias is a free form modelling program that can create “A class”(aesthetic) surfaces. They will take the designers’ initial sketches (and input) to interpret them into a 3D model. A good designer should be able to think in 3D, but CAD modellers are exceptional at it.

Their expertise is working out how the surface transitions from one to another: How does that wheel arch flat become the wing, and then flow into the A-pillar? Their data will be used to mill the initial full size clay models at the beginning of the design, and I’m pretty sure CAD modellers are exclusively powered by snacks and mugs of tea; one CAD guy I knew had a fresh pack of 12 cakes on his desk every morning.

Another of Earl’s big innovations was the introduction of clay models into the design process. The clay modellers are the sculptors of the studio. Although the 5-axis milling machines can create a full-size model in a few days to a high degree of fidelity, the model surfaces are always finished by hand, using strips of steel or carbon fibre known as slicks. Clay modellers obtain and make their own tools; rakes and scrapers of all shapes and sizes. Like a set of chef’s knives, they are the personal reflection of the skill and care they put into their work.

Clay modellers are also responsible for dressing the models – making them as realistic as possible for review. If changes are made on the clay, they will scan the model and depending on how mature the design is, feed that data back to the CAD modellers or the surfacing team.

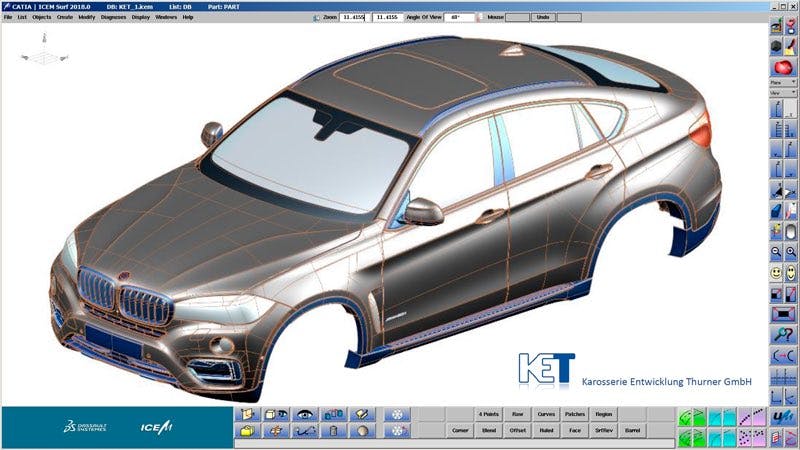

The surfacing team creates the actual production data for the “A” surfaces, which is then sent to suppliers. They rebuild the Alias software data from the CAD team (which is essentially quick and dirty for creative purposes) into production-ready models. Using a program called ICEM Surf (a distant relative of a program originally developed by Volkswagen in the late 1970s) these surfaces are signed off by a design manager and released to the appropriate engineering teams to have the “B” surface added, then sent to suppliers for validation.

Usually the data comes back with suppliers complaining that a part can’t be pressed or moulded, and can we please tweak it? It’s then up to the designer to ask the surfacing modeller to undo their hard work and rebuild it; I once had the joy of redoing a load of alloy wheels that kept coming back as not strong enough, and by the end of it the surfacing modeller was giving me the side-eye every time I approached their desk.

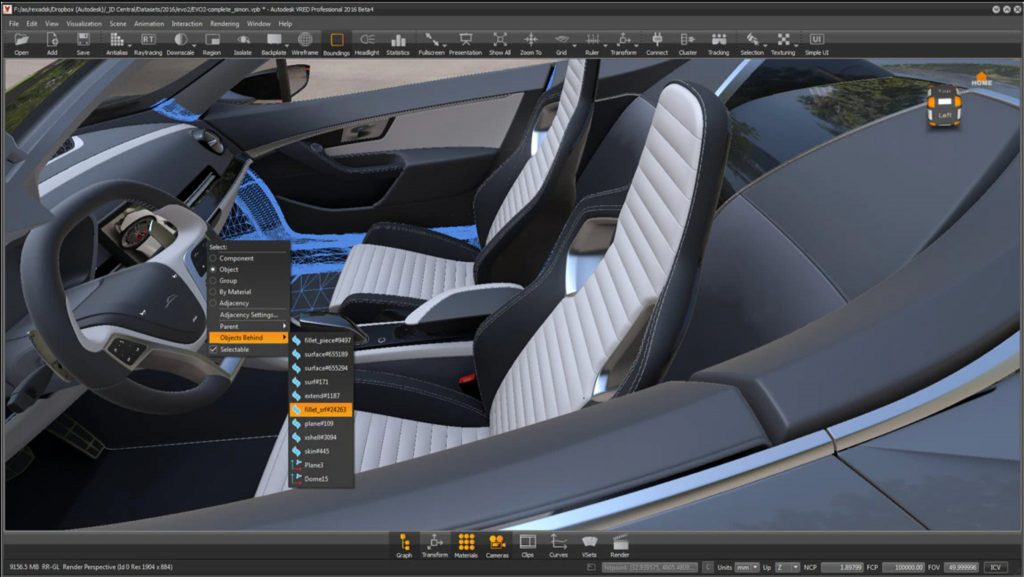

The visualisation team takes the most up-to-date model data (exterior and interior), drops it into rendering software, and creates visuals for internal presentations, reviews and brochures, product animations, and building configurators (like the ones on manufacturer’s websites, but for internal use only). If a studio has any VR tools, this team will set up the environments and the gear.

As part of a designer’s role is preparing images for reviews, it’s extremely handy to pull up the model in the configurator, select the appropriate trim level and colour, set the camera to the desired view (although a “studio standard” set of views preferred by management is likely) and render a high-quality set of images that can be scrutinised on a powerwall (a massive screen, not a recycled Tesla battery). Autodesk VRED is the most common software used, although Epic Games with Unreal Engine have been looking to steal Autodesk’s lunch recently.

The final link in the modelling chain are the model designers, sometimes called model operations. Even if it’s a clay model, the armature (or buck) that the clay sits on has to be designed and engineered, as clay models are heavier than the real car. This team makes hard model parts milled from foam, cast in GRP or 3D printed, and then made in the model workshop: Things like door handles, lights, mirrors, wheels, grilles, and additional details add to the illusion of realism. If a full-size hard model is required, this team creates and builds it.

Given enough time, it’s entirely possible to build a full-size hard model that to the untrained eye is indistinguishable from a real car. I spent months supervising the building of two models that were going to be used in the launch of one of our new vehicles – checking panel gaps and tolerances and making sure they were as representative as possible of the real thing, even down to making sure the correct tyres were fitted.

These are the main roles that work together (not always seamlessly) to bring a design off the page and into the real world. Next time we’ll take a deeper look at the various types of models, and why physical models are still critical in an increasingly digital world.

This article, part of a series on car design, was originally published by Hagerty US.

More on car design

What makes good car design? An industry insider peels back the studio curtain

How are cars designed? An industry insider takes us through the steps

Cabin fever? 12 wild interiors from a dozen decades of the car