Editor’s note: This story was originally published in Hagerty Drivers Club magazine, in America.

Drive too quickly out of the village of Crewkerne in England’s pastoral southwest county of Somerset and you’ll bolt right past Ariel’s headquarters. There’s no sign out front, Ariel apparently trying hard to look no more interesting than a couple of red-brick tractor barns. But pull through the fence and into the courtyard and you’ll likely see the nose of one of the company’s skeletal road rockets poking out of a garage bay.

We were greeted by Henry Siebert-Saunders, managing director and son of company founder Simon Saunders. Parked in the courtyard was a freshly completed Atom, the company’s signature two-seat mid-engine speed toy, plus a mud-caked Nomad, the Atom’s off-road cousin. Just visible through a doorway was an Ariel Ace motorcycle, an organic sculpture of cast and machined billet aluminium packing a 1237cc Honda V4 and emitting 1000 rads of radioactive attitude.

Ariel is a family affair, the two Saunders presiding over a workforce of 30 that aims to build 100 cars and perhaps 30 motorcycles each year.

“A lot of people are obsessed with growth,” Henry tells me. “We have not grown in 10 years. If you can keep a steady business, growing just enough to support price increases and whatnot, we can make this a business for life.”

Ariel is one of those ancient British nameplates that died only temporarily. It dates to 1871, when bicycle makers James Starley and William Hillman named their first product after the character of Ariel, the spirit of the air, from the Shakespearean fantasy frolic, The Tempest.

Ariel the subsequent car and cycle maker was best known for its Square Four motorcycles, built from 1931 to 1959. They were exquisite odes to British complexity, featuring parallel pairs of cylinders under chain-driven overhead cams, and twin counter-rotating crankshafts linked by intermeshing gears to merge their torque. Ariel was absorbed by BSA in 1951 and production of anything bearing the name petered out in the early 1970s during the great British bike collapse.

It was resurrected when car designer Simon Saunders, who previously designed for Porsche, Aston Martin, and General Motors, decided to try his hand at producing a modern take on the 1957 Lotus Seven, the grandpa of postwar British roller skates. His 1996 concept, unambiguously called the LSC for Lightweight Sports Car, debuted the naked aluminium trusswork that was to characterise all future Ariels, which look like Formula Junior entries for some futuristic Grand Prix du Pluto.

“We wanted to create a reliable, dependable thing that you can treat like a normal car,” says Henry about the Atom, which has long put ultra-reliable Honda Civic power (early cars used Rover K-series engines, much like the Elise) behind a frill-free cockpit open to the wind and rain. “We tell people that if you take the body panels off a Ford Mondeo, it would be an Atom.”

Well, not exactly. The 600-kilo car is basically what you’d create by slinging a jacuzzi between two Ninja sport bikes. It’s fairly easy to drive, and the components are all modern and reliable automotive spec, but without ABS and stability control (the newest version has traction control), you are master of your own fate. “Our current record is 11 miles, showroom to crash,” Saunders says.

Production units began dribbling out in 1999, but it was a 2004 star turn on Top Gear that lit Ariel’s fuse. In the nine-minute segment (now viewed 12 million times on YouTube), host Jeremy Clarkson circled a track with his face hilariously puddled by wind and g-forces as he screamed with joy.

“Everything changed,” says Henry. “Our order book went from a six-month wait to 28 months overnight. Our phones did not stop ringing for 18 months.”

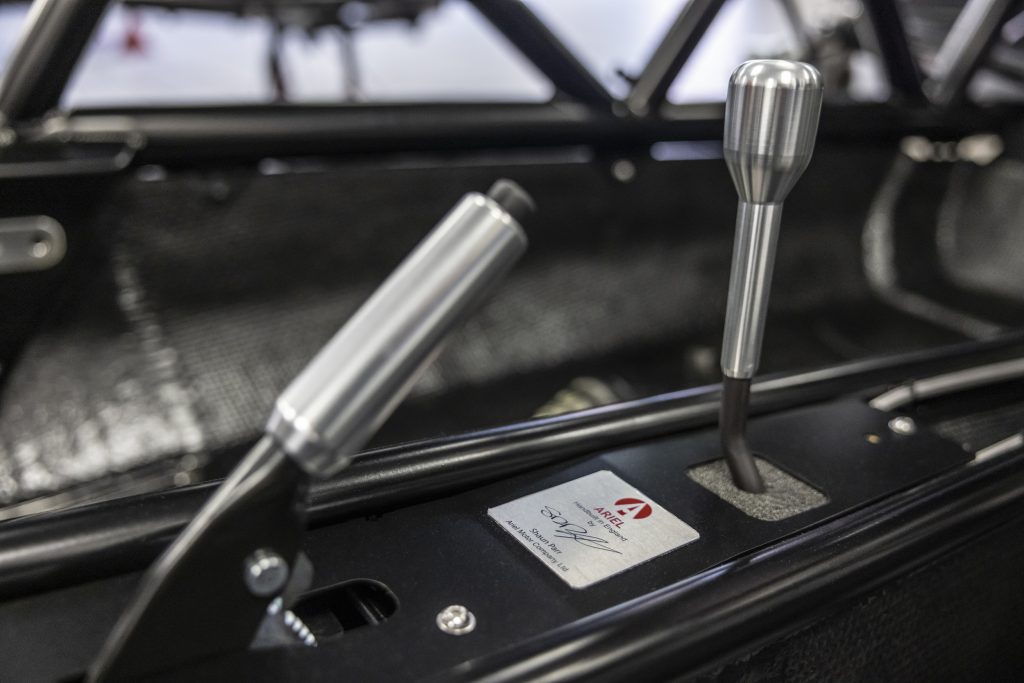

Ariels are hand-assembled by individuals working in bays in the workshop, one at a time over 140 to 160 hours from outsourced components – 75 per cent of the parts, from the steel frame to the Aim electronic instrument cluster, are British-made (though the 1.5-litre Honda turbo comes from Ohio). Each car is signed by its assembler.

Despite a line of mostly British customers and a favourable legal environment that shields cottage builders from safety regulations that affect larger manufacturers, staying alive is an everyday challenge. At the time of our visit, the company’s electricity bill had just jumped 300 per cent because of energy shortages caused by the Ukraine war. Henry figures Brexit has added £1500 to the car’s price and made it more difficult for certain EU customers to register their cars.

And the UK is threatening to ban sales of internal-combustion engines by 2030.

“If they pass [an EV mandate that doesn’t exempt small producers], we go out and pull the door down, we’re done,” says Simon Saunders. The EU has created an exemption for car companies building fewer than 1000 cars a year, and the British government says it is considering a similar approach. “It’s on our minds. We know we have to electrify, but we don’t have the resources to develop an electric car on our own. We have to wait for the industry to do it.”

This article was originally published on Hagerty US.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage for daily news, features, interviews and buying guides, or better still, bookmark it.