Infatuated with going fast, Paul Newman played a racing driver, then became one, and photographer Al Satterwhite was there to capture his journey. Charlotte Vowden speaks to the man behind the camera.

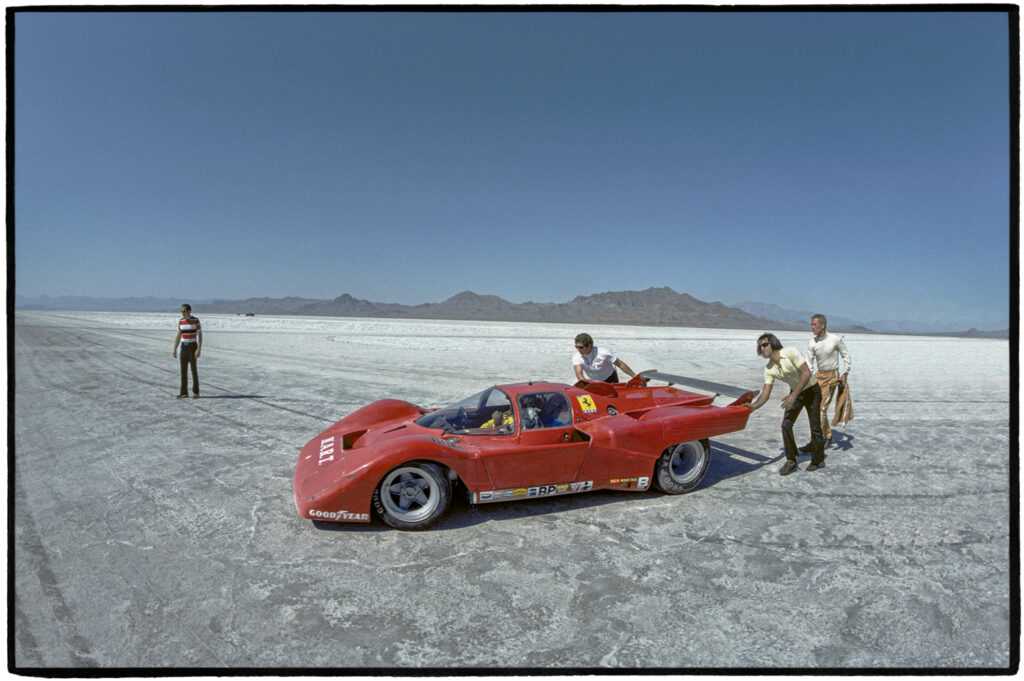

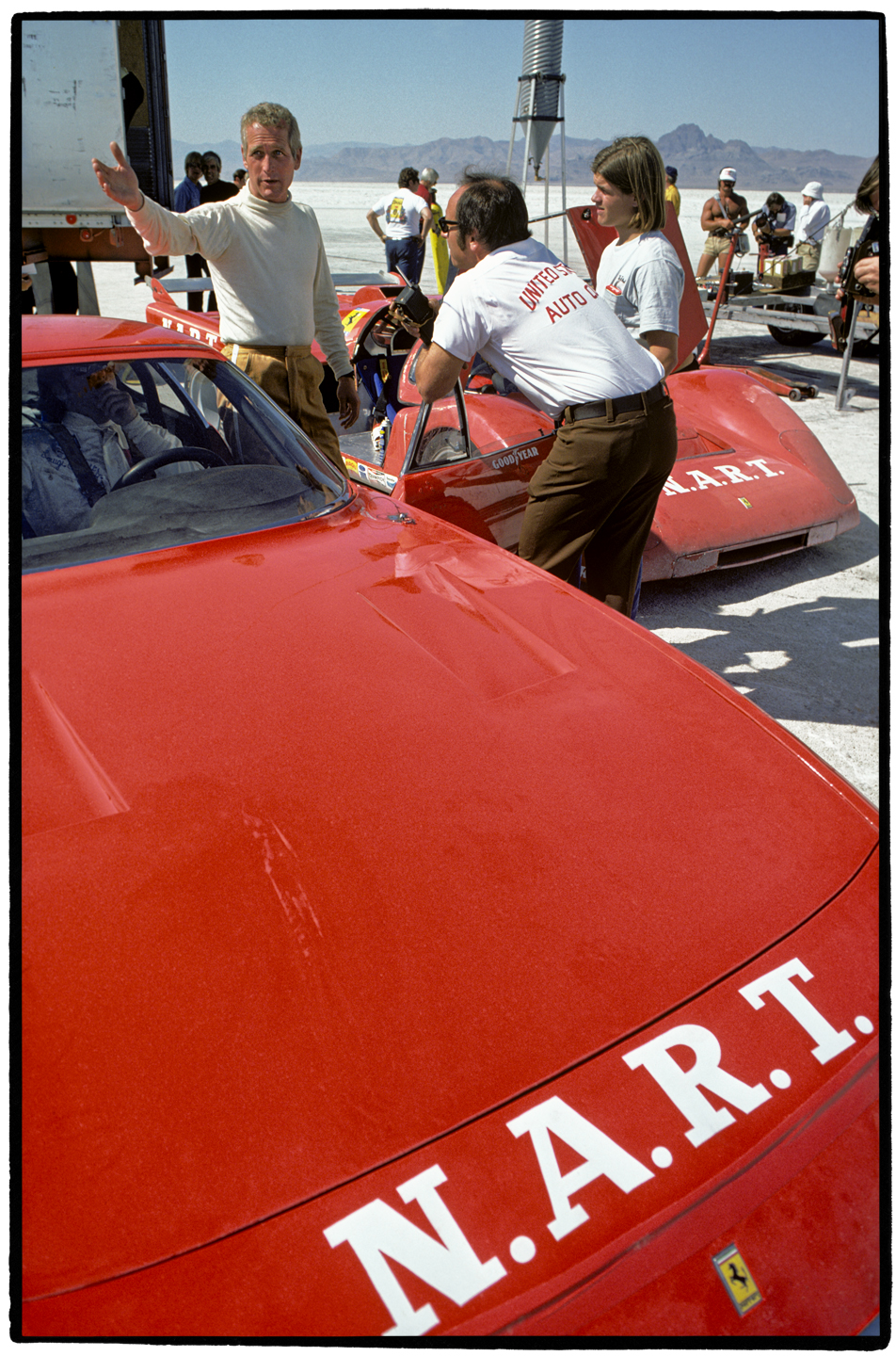

Morning has broken and photographer Al Satterwhite is up and at ’em. The sun, still low on the horizon, reveals a stark and unforgiving landscape; he can see the curvature of the earth. Deserted at present, the Bonneville Salt Flats will soon become the setting within which four men intend to show the world what can be achieved behind the wheel of a couple of ageing Ferrari race cars. It’s the 22nd September 1974 and on assignment for Sports Illustrated magazine, Satterwhite is there to capture a land-speed record exclusive, which happens to involve the greatest celebrity racer of them all.

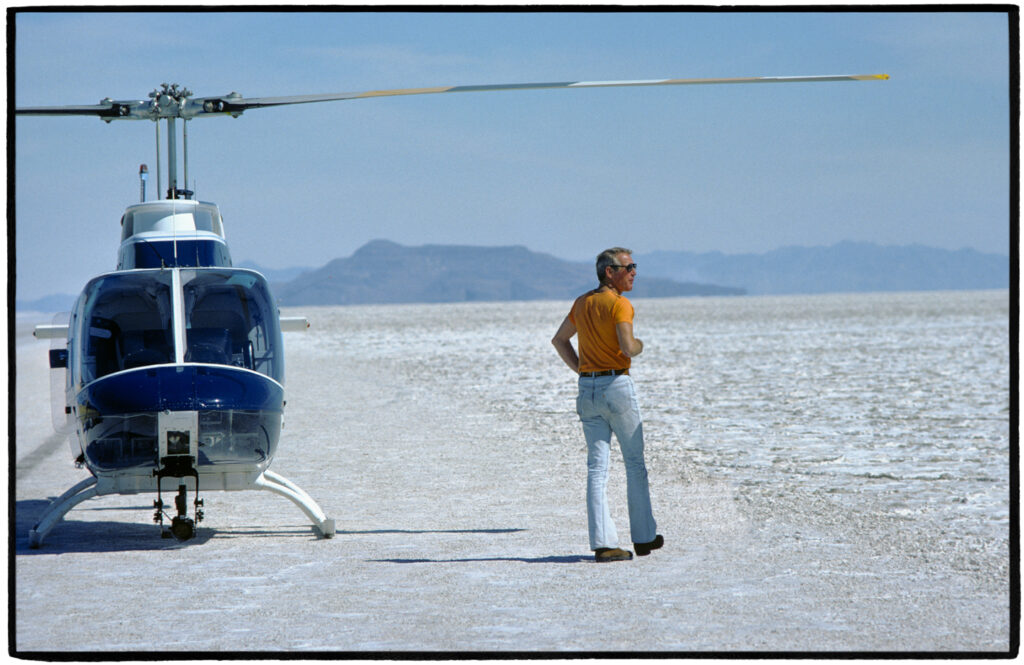

“Paul Newman shows up because he’s a good and respected driver, but then a Jet Ranger helicopter shows up because a news crew got wind of the story,” explains Al. “Chinetti [Luigi ‘Coco’ Chinetti Jr] who had organised the whole thing probably told them for a little free publicity, but Paul locked himself in his trailer, called his agent in New York and hammered out some sort of arrangement.”

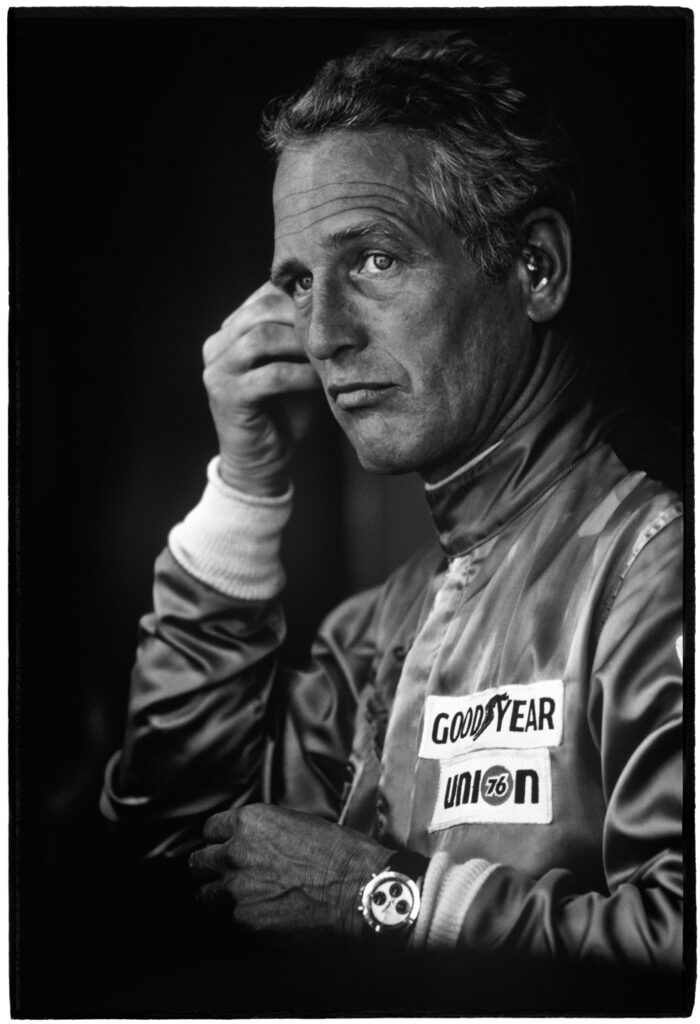

Preferring to stay away from the flashbulbs and glitzy milieu of Hollywood, Newman’s aversion to performing for the paparazzi set him apart from many of his movie star contemporaries, and his cool, confident demeanour lent itself well to motorsport. “Newman was more worried about his driving abilities than his dealing with the network, he was there to have some fun, it was his passion and other drivers sensed that.”

A deal was struck and the day went ahead as planned, but for Satterwhite, it unfolded with the surprise bonus of a ride along in the Jet Ranger. “I went up with the pilot and we flew around the course so I could shoot some aerials. I always try to get a variety of stuff but that was a totally different and unexpected perspective.”

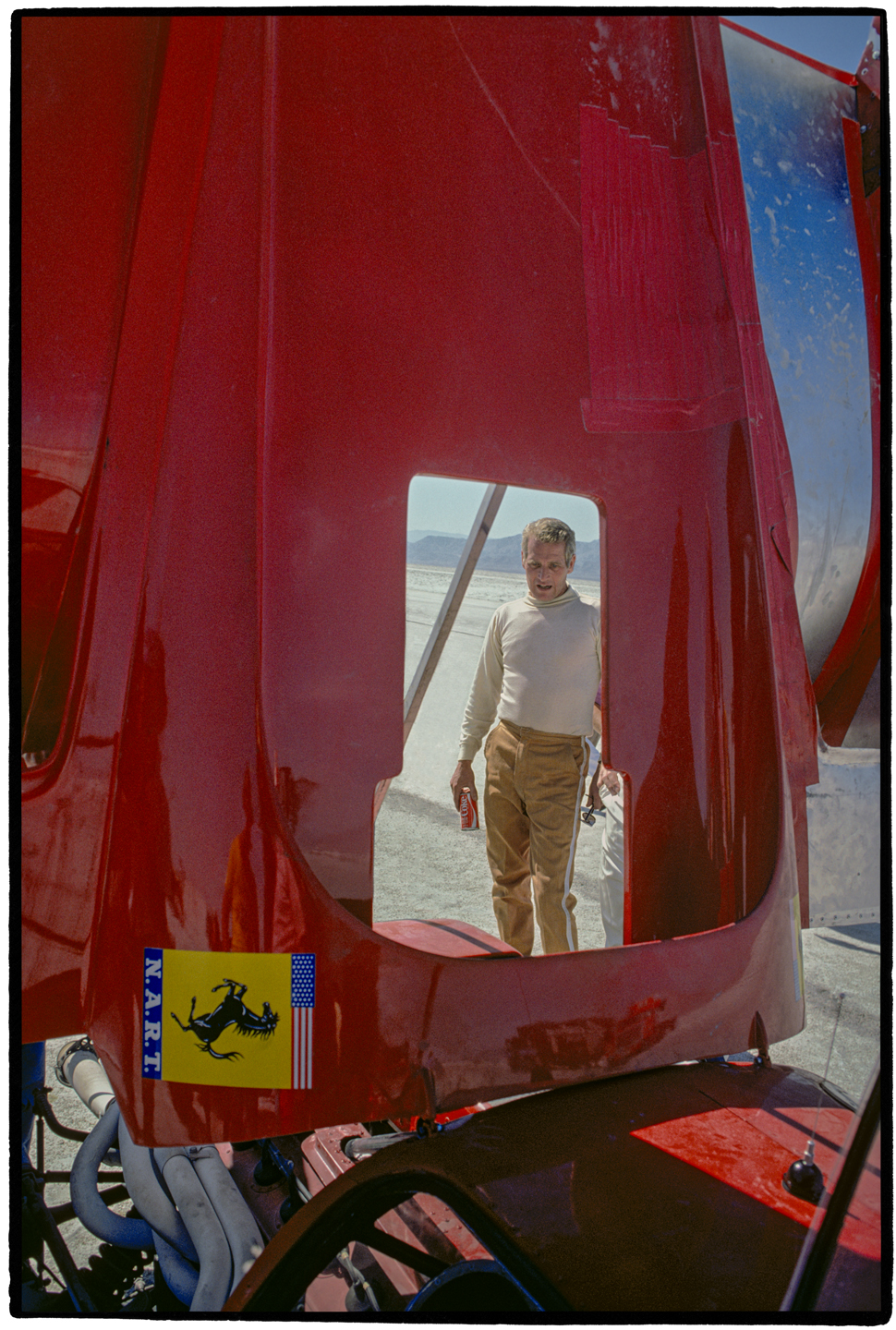

With his feet firmly back on the ground, but likening his approach to a “fly on the wall”, Satterwhite went on to capture Paul “in racing mode, which meant happy mode” for more than a half decade. These are some of his favourite shots, which can be seen alongside other images from Al’s archive in the coffee table photobook Paul Newman: Blue-eyed Cool.

Thrashing Ferraris and shooting pool

“As much as I like cars, I like the people a lot better; the drivers, the mechanics, the crew, it was always much more interesting to shoot them, and this was the first time I shot Paul. I didn’t think of him as an actor because that wasn’t part of the deal; I wasn’t there to cover Paul the movie star, I was there to cover Paul the driver and I spent as much time shooting the other drivers [Chinetti, Graham Hill and Milt Minter] as I did him. That night, we all had dinner at the local watering hole which had a pool table that Newman eyed. People were reticent to volunteer so I said ‘Okay, I’ll play’. Luck prevailed and I actually beat him, barely, and although I think he was in shock, he was a gracious, straightforward character who was a lot of fun to be around. I don’t tend to get super friendly with subjects because I don’t want to impinge on them, especially somebody like Paul who has to deal with people like me for hours every day. We didn’t stay in touch, but when I’d see him at races, if I’d wave, he’d wave back.”

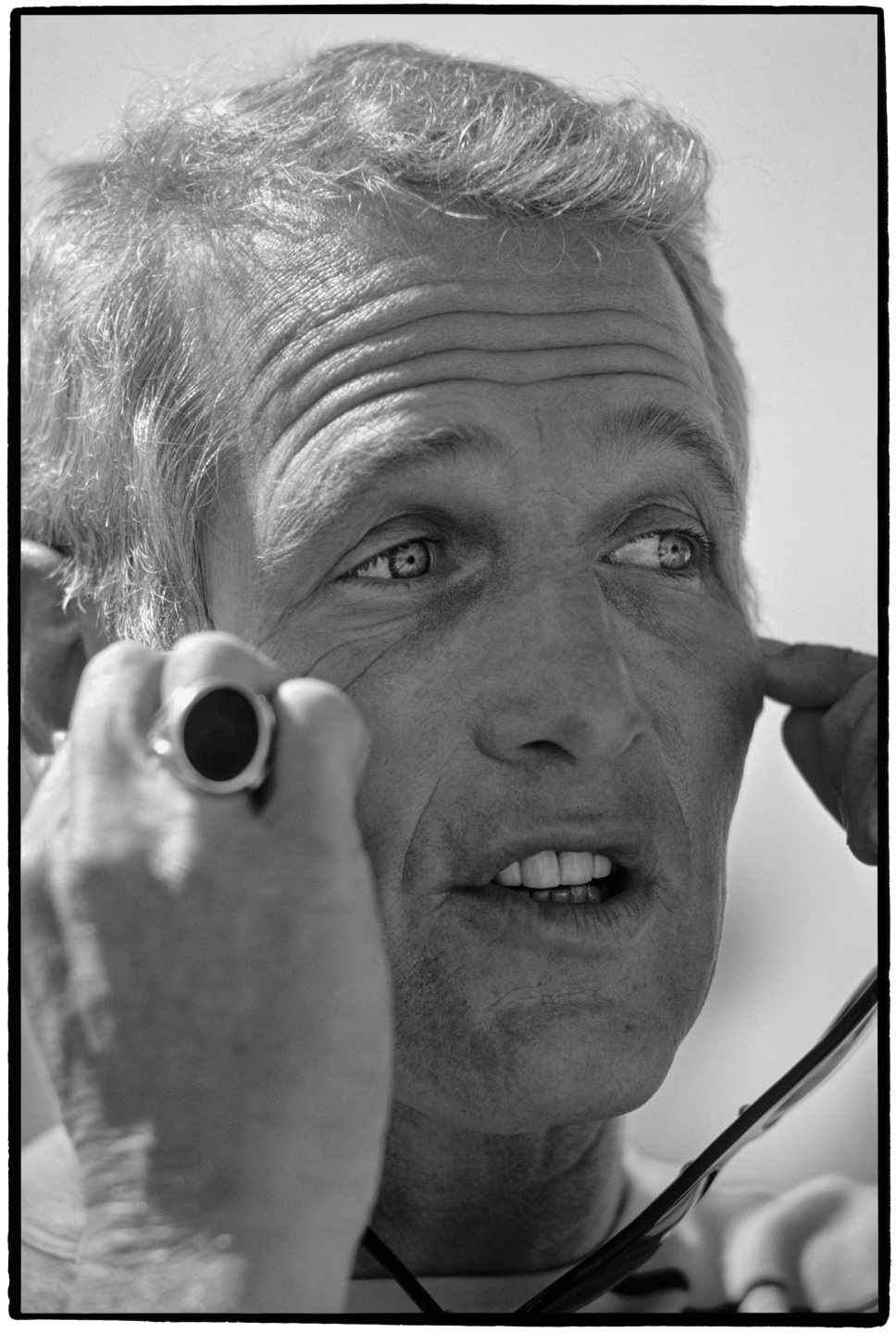

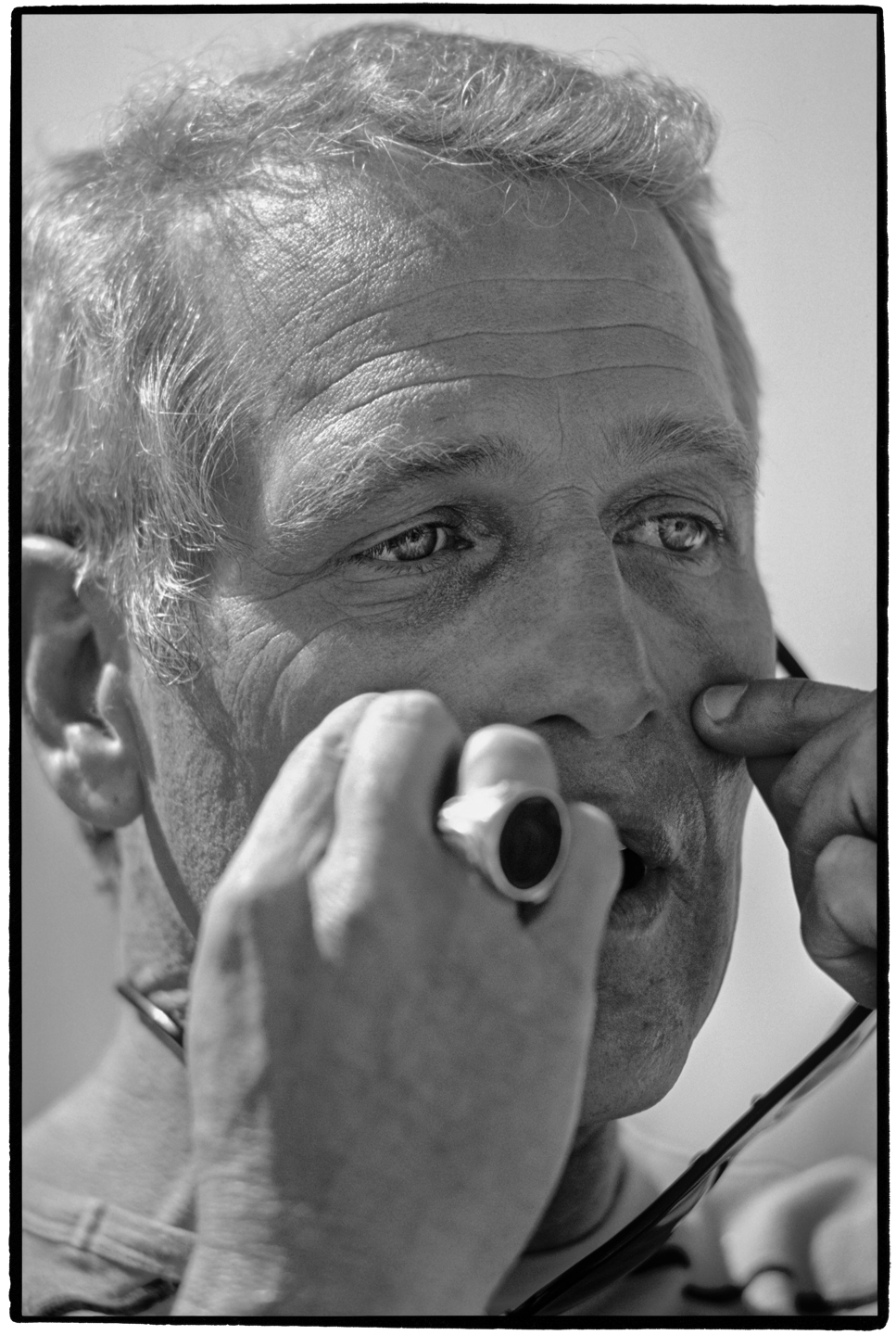

“Paul was a good looking guy and he was smart, but you saw somebody different when he was racing because he wasn’t acting; he was 100 per cent the real Paul. You can tell he’s having a good time in so many of the shots I took of him; he was focused when he was out there, but in-between he looked like a kid in a candy store.”

“A normal race track is made of asphalt and as the heat builds up through the day you have to deal with heat waves which, when you’re trying to shoot through them soften the image; it’s like shooting through a dirty filter. I tended to shoot with the slowest speed film which made the cars look sharp and the background blurred to give a sense of speed. In those days I tended to work with multiple cameras and each one had a different lens on it so I didn’t waste time, I loved Leicas and Nikons – us photographers looked like portable camera stores.”

Photographing a star from afar

“We used to be able to work in the pits, you just had to be very careful not to get hit. It was a matter of trying to place yourself where you can get a good shot without interfering, which in a race setting is easy to do because there’s a lot of commotion and people tend not to pay attention to photographers. I had to be ready with my cameras set to get things that caught my eye but I also anticipated how situations might develop into a photo opportunity. I thought if all the photographers are going over there, then I’m going somewhere else so I didn’t get the same shot – it didn’t always work out.”

“I had 36 shots to a roll and a lot of times my best shot would be 34, 35 and 36, and that’s because you are watching the subject and waiting for something to build up to a climax. They could be telling a joke or a funny story so you know it’s going to get better and you save a few frames because you don’t want to be out of film when that moment happens, and believe me it’s happened. I love digital cameras, but the problem with being able to fire away forever is that you’re not really looking for the actual moment you want to shoot. You need to focus on what you’re trying to capture, ask yourself why am I taking this? I still only shoot two or three frames.”

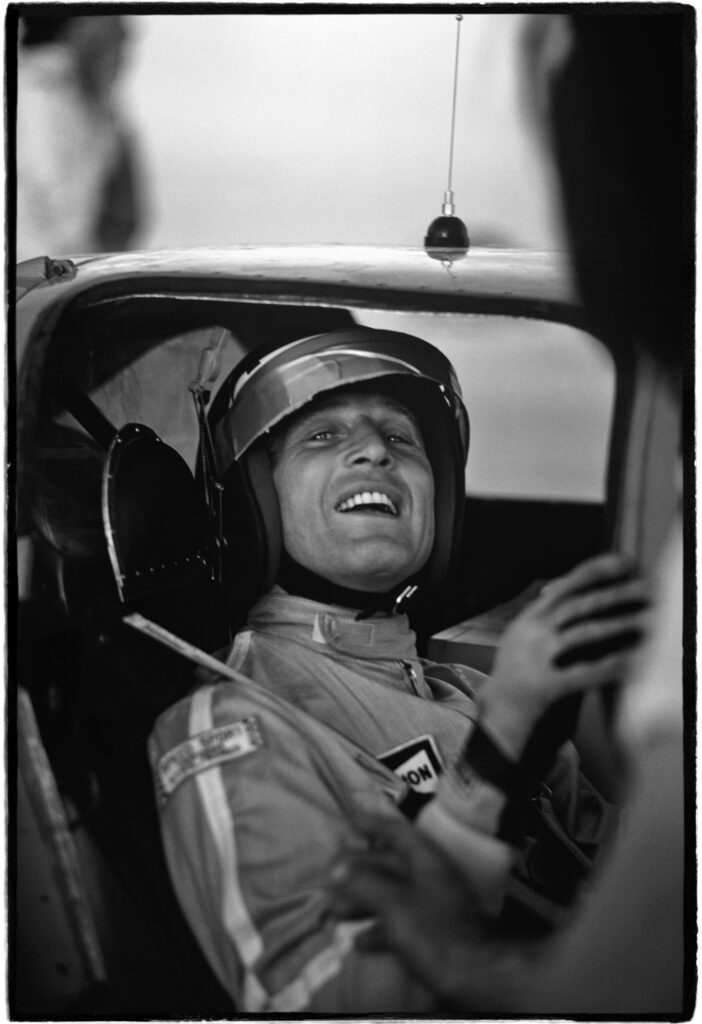

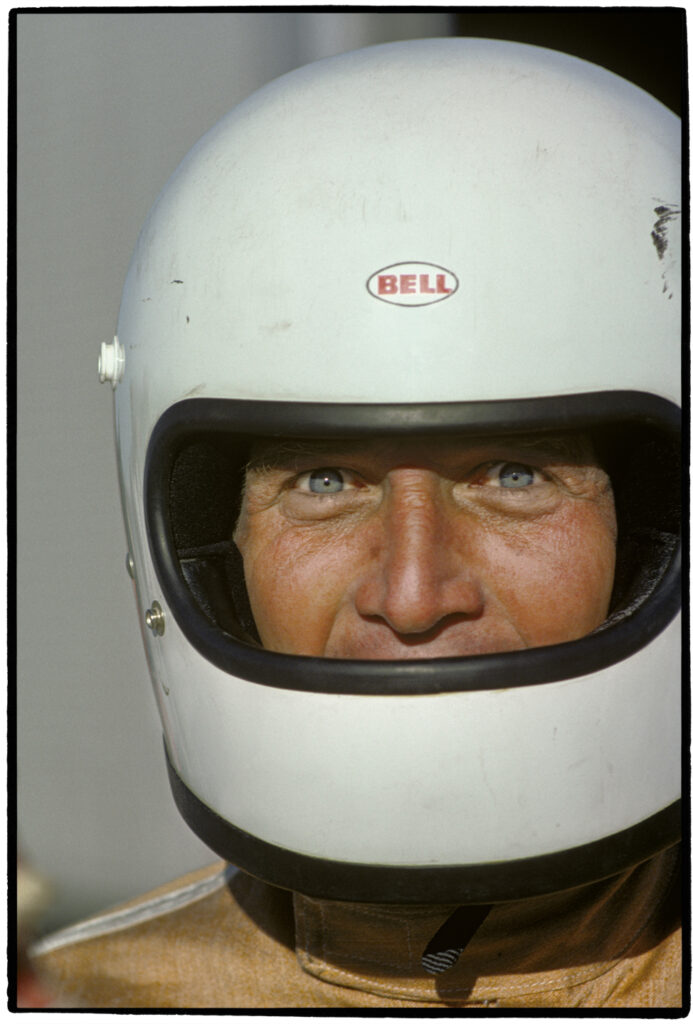

“The adrenaline running through the drivers in those days must have been unbelievable. For me, this shot stands out because Paul’s got this intense focus, there could have been a circus going on next to him and he wouldn’t have paid any attention to it whatsoever.”

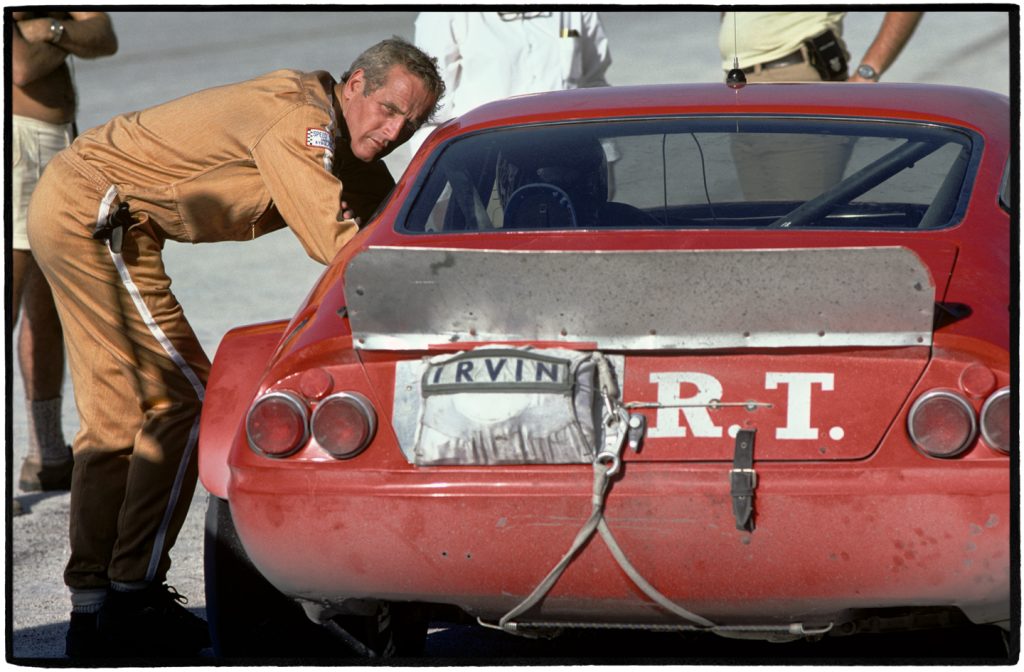

“For Paul, racing was serious: he was going out there to win. Leaning into the Ferrari Daytona here he was getting ready to go out, or just coming in, and it’s at this point when another driver takes over that they talk to each other about the conditions on the track or something about the car.”

Blue-eyed cool

“When you shoot a car you can’t always tell who the hell is driving it is unless you recognise the helmet, but with Paul, how could you lose him with those blue eyes?”

“In those days I was constantly in motion, jobs kind of ran into each other, but it was a great time, I treasured every moment, it’s what those of us in the industry called the golden age of photojournalism but it’s not like I was making an incredible fortune, the pay wasn’t all that great! The adventure and the access that you had being on the front line, that’s where it was at – even if some of it was a blur.”

***

To see more photographs of Paul Newman’s career on the circuit, Paul Newman: Blue-eyed Cool, written by James Clarke and published by ACC Art Books, is available to buy for £45

Read more

11 Hollywood heroes who felt the need for speed

Dieter Klein travels the world in the quest for the perfect photograph of abandoned cars

It took 10 years to photograph but Made In Italy was worth the wait

excellent story telling – as told

Thank you for sharing those experiences, and the advice, Al.