On a sunny afternoon during lockdown, lubricated by a few birthday beers with his family, Jon Newall bought a little-known EuroBrun Formula One car.

It wasn’t an accident of course, not the carbuying equivalent of those people getting blind drunk and waking up bobbing in a fountain in a city on the other side of the world. But nor did Newall necessarily expect to end up as the highest bidder on a 1988 EuroBrun ER188 on his birthday in 2020.

“I started bidding and it wasn’t that fast and furious. I bid up to a certain amount and thought, ‘You know what? I’m just gonna leave it there.’ It’d be a nice idea of course, but I knew it was going to keep going. So I put in a few thousand shy of my maximum bid, and then it stopped. And I remember my wife looking at me, because I had this look of shock on my face, and saying ‘What have you done?’”

EuroBrun was one of Formula One’s many near-forgotten flashes in the pan. The Milanese constructor entered 46 Grands Prix in the late 1980s and early 1990s, starting only 21 of them.

It had entered Formula One in 1988, financed by Walter Brun, best known for his endurance sports car teams. Brun did what most F1 garagistas had done over the past few decades, sending some money Cosworth’s way for a line of fresh DFZ engines – an evolution of the DFY which itself had evolved from the dominant DFV – and handed the engines to Swiss engineer Heini Mader, who had found his break in F1 as a mechanic for Jo Siffert.

Like so many backmarker teams, EuroBrun didn’t have things easy, with frequent retirements and then, as money ran low, struggled to even pre-qualify. Despite the efforts of Stefano Modena in 1988 – a driver whose string of tail-end cars never did justice to the 1987 F3000 champion’s resume – the highest position the team would ever achieve was an 11th-place finish at the Hungarian Grand Prix. Operating on a shoestring, often running different liveries on its two cars, EuroBrun shut up shop with two races to go in the 1990 season.

Then, in 2020, fate brought Newall together with ER188-003, one of the cars raced by Modena in that first season. In fact, it brought him together with two.

“There was a EuroBrun for sale literally 50 miles from my house in a liquidation auction for a specialist car dealership” says Newall. “So I went to have a poke around and I thought, man, this could be fun. The only problem is that I had a limit on the spare cash in my pocket.

“In the run-up to the auction I noticed that there was another for sale in an RM auction in Essen on the very same day! In the morning, the local car, an ’89, went to my limit, but plus VAT…” he sighs.

“Anyway, it was my birthday party, I still had my family around me, my brother had moved in for lockdown, and we were having a few beers. But I’d hedged my bets and pre-registered for the Essen auction. I think it was the right car for me, but in the wrong auction, so I was very lucky – it wasn’t in a race car auction, so it didn’t have the right audience.”

And, after a winning bid and a withering look from his wife, Newall had an F1 car. It was largely complete too, with the engine and gearbox, albeit the wrong livery, and had been living in the Boxenstop Museum in Germany for, Newall thinks, about 21 years. He arranged transport, and then spoke to a friend, Mike O’Connor, from F1 car owners’ group Fastest Club for some advice. “It turns out he was the guy I was bidding against!” Newall laughs.

What came next was a comprehensive rebuild to turn a museum piece into a car that could be enjoyed on track – because Newall’s a firm believer in using his toys, even those with motorsport history. A fascinating parts-hunt ensued, throwing up a quirk of the classic F1 market: the fact that old parts often end up in display cases and on mantelpieces all around the world.

“Largely the car was in good nick, it just needed taking apart and every little bolt and washer and nut replacing just for safety’s sake. We had the chassis X-rayed, and other metal parts crack tested and brought back to life, too.

“But we had some nice people when I joined the EuroBrun Facebook group – there were people in Australia who had parts and sent them over! I have to give a shoutout to Roy Michie out there, who sent us a bunch of gearbox parts that he had. Other people would say things like ‘Oh, I’ve got a souvenir from a EuroBrun’, and we were like, ‘That’s a part we can use, once we take it off the wood plinth it’s mounted on.’”

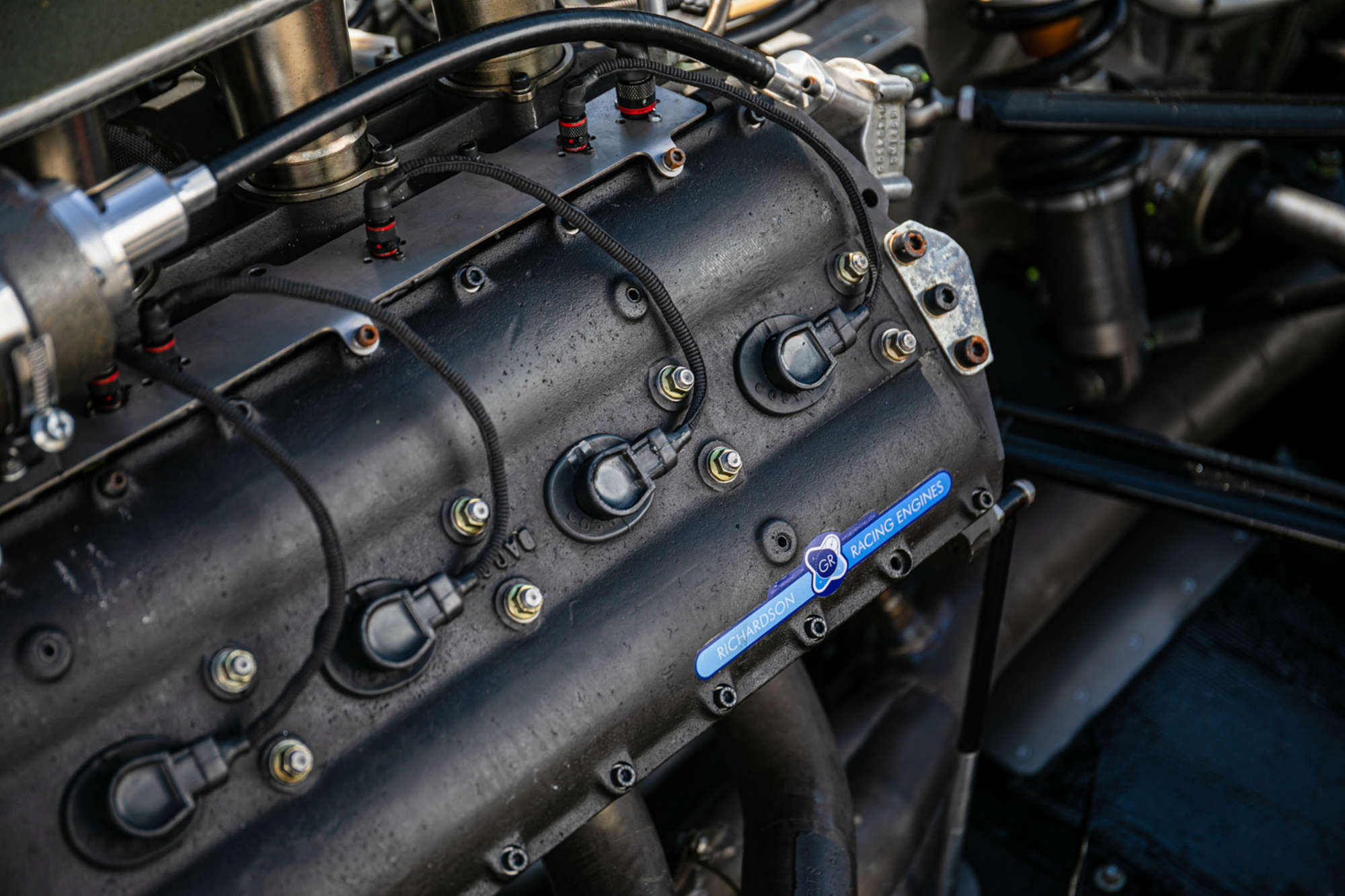

Newall’s desire to properly use the car though presented the biggest single bill of the project: having the Cosworth rebuilt.

“We went to Geoff Richardson, who was Patrick Head’s former business partner, and is the god of Cosworth DF engines. And I won’t lie, the bill for that was absolutely eyewatering! He said, look, we can either do it and run it, for eight to ten grand. But because it’s been stored, you don’t want to do half a job, destroy the engine, and end up with an even bigger bill. It ended up at more than £40,000 to have the engine brought up to peak condition.”

Surprisingly, the car doesn’t take a great deal of effort to run – typically just two mechanics. While the DFZ needs preheating, it’s the work of effectively two feed lines, one for coolant and another for oil, and a couple of hours of time – certainly less involved than it would be with later F1 cars.

The cost and minor inconveniences are worth it, however. Even running with a rev limit of 11,500rpm – down from the 13,500rpm it’s capable of, to extend major service intervals to 1000km from a 300km race distance – the car is making around 560bhp, pushing along a 560kg chassis. One horsepower per kilo, not including the driver.

“Have you ever had an experience where you’re accelerating so fast, all you can do is laugh because your brain can’t process it? After the first time I drove it I had to sit in the car for 10-15 minutes with the engine off before I could stand up, it was mind-blowing, and it totally redefined what fast is to me.”

The gearshift proved an unexpected highlight, and immediately quelled any concerns of expensive mis-shifts. ‘It’s without a doubt the sweetest gearchange I’ve ever experienced. It just slips between gears. The race team said, ‘Once you’re going don’t use the clutch’, and the amazing thing is you don’t even need to ram it between gears – it’s just a finger touch from a lever barely taller than your hand. The bottom of your hand basically sits on the chassis.”

The downforce took much more getting used to. “It scared the living crap out of me! It’s true what they say, that the car is harder to drive if you’re not pushing, because you’re not getting the aero. You need to get your head around the idea that if I go faster into that corner, I won’t lose grip.

“Then there are the brakes. The first time you almost come to a standstill, until you realise you need to go past several of the brake markers you’d be using in any other racing car. If it’s this much of an assault on the senses in a 35-year old F1 car, you’ve got to have a hell of a lot of respect for Verstappen and Leclerc and the like in far more advanced cars.”

The one thing modern drivers don’t have to deal with is finding a place to drive their cars, but with facilities like Blyton Park and airfields like RAF Bentwaters, there are more than a few locations in the UK for private F1 car owners too. Bigger invites have apparently come in to circuits like Brands Hatch and Spa, but as a fairly private individual, and not wishing to damage the car (particularly in front of large crowds), he’s politely turned them down.

And now, having brought back a largely forgotten part of Formula One history, it’s come time to move the car on. For sale through Silverstone Auctions this August at The Classic, ER188-003 carries a guide price of £225,000-£275,000 – and the prospect, as eligibility requirements shift, for entry into events like the prestigious Monaco Historic.

It’s clearly a bittersweet decision for Newall, though the joy of having restored the EuroBrun – and parked it next to his Group B Audi Quattro, experienced that power and downforce for the first time, earned newfound respect for its drivers, and learned about a car that few really gave much thought to even in its day – has clearly been worth it.

If it doesn’t sell, says Newall, “I’ll find a good pedaller and take it to Monaco. I’ve not got the fortitude to go around that circuit myself!”

And if it does? “I still think there’s an undiscovered chassis out there in someone’s garage. I’d love to find it and do it all over again…”

If you do, Jon, that next beer is on us.

Read more

The likely lads in a lock-up who made it to the F1 grid

Masterclass: When Nigel Mansell destroyed Nelson Piquet at the 1987 British Grand Prix

The need for speed: buying a classic Formula 1 car

lucky bugger