Editor’s note: This story was first published in the US edition of the Hagerty Drivers Club magazine.

Robert Loydell of Aston Martin Works extended a hand covered in that fine sheen of grime you get from working with old tools. I took it gladly and shook it firmly. Loydell walked me over to one of two massive C-clamp-shaped English wheels, both of which have been at the factory since before the Battle of Britain.

“These would have made the panels on some of the aircraft we made here during the war,” he said.

My heart leaped into my throat, wondering if this cast-iron monster had made parts for the planes flown by my grandfather, a wing commander in the wartime Royal Air Force. As Loydell handed me a sheet of aluminium that I tried to bend into a voluptuous shape vaguely resembling a DB5 wing, Aston’s PR man leaned over with some urgency and said, “Please, let me just say to be exceedingly careful when using this.”

No, Aston Martin isn’t just any other car company. Look past the glamour and style, past the slick new Formula 1 team and today’s carefully crafted brand image of a tuxedoed James Bond stepping from his carbon-fibre road missile (equipped with real missiles) and see a company that has been building cars since King George V sat astride his horse. Most companies never get the chance to survive a single bankruptcy, yet this one has survived seven. When the stock price fell below a dollar in 2020, one might have considered that a dalliance with number eight. But, somehow, Aston Martin keeps bouncing back.

The answer as to why might be discovered, I thought, if I travelled to a sleepy, two-pub village 50 miles northwest of London called Newport Pagnell – not as one of the regular visitors to the dealership who comes to purchase a new car and select leather swatches, but to get my hands dirty with the people who repair, rebuild, and restore the cars. I wanted to see exactly how the magic happens at the historic home of this storied British marque. Fortunately, Paul Spires, president of Aston Martin Works, was game.

In 1947, David Brown, a machine tools manufacturer, bought Aston Martin, which had already experienced two financial collapses since its launch in 1913 by Lionel Martin and Robert Bamford. Brown moved the business from its headquarters in Feltham, West London, out to Newport Pagnell in 1955, where a three-story building topped by a weathervane served as the original coach house facility. Brown believed it would be more efficient to build an entire car in one location rather than build a chassis in one place, the engine in another, and have coachwork assembled somewhere else. That building on Tickford Street across from the current Works location still stands. It predates the internal combustion engine and, according to Aston Martin, is the oldest surviving car factory in Europe.

Spires packs a schoolboy mischief into his youthful 50-something manner. If he was trying to rein in his enthusiasm for Aston Martin, which he joined in 2012, he failed miserably. By way of introduction, he rolled through some interesting but studied figures: In 2021, which was the 108th year since Aston Martin’s founding, the company produced its 100,000th car, an impressive number considering how rarely you see an Aston Martin on the road (but one that Volkswagen Group matches every four days across its various brands). Unlike VW, however, Aston estimates that 95 per cent of all the cars it has ever built, including the 13,300 originally produced at Newport Pagnell, still exist and are either roadworthy or capable of being so with a certain amount of “fettling,” as the British call it.

That is where Aston Martin Works comes in. A subsidiary of Aston Martin Lagonda, which produces pricey luxury sports cars and SUVs at factories in central England and Wales, Aston Martin Works’ main business is all that fettling of vintage Aston Martins and treating new ones to special modifications for owners who want their cars done “by the factory.” In recent years, Works has also branched into the business of completely reproducing obsolete Aston models from scratch – and for astronomical prices. Currently, it is wrapping up a 25-car run of the DB5 Goldfinger, which – at around $3.5 million (£3m) a copy – can put you behind the wheel of the hero vehicle from the 1964 James Bond thriller of the same name, complete with working spy gadgets. Previously, Works built continuation runs of the 1959 DB4 GT and 1960 DB4 GT Zagato.

To the untrained eye, Aston Martin Works appears to be nothing more than a modern dealership. The smooth sandstone walls of the outer building frame floor-to-ceiling windows showcasing contemporary DB11 V12s and DBS grand-touring cars awaiting a keen test driver. But go past the glassy facade and you’ll find a company successfully straddling the line between preserving its past and reinventing itself for the future.

For 11 years, Loydell, the metal craftsman who’s been recruited to babysit me in the panel room, has worked here shaping the bodies of some of Aston Martin’s most beautiful works of art. Before Loydell handed me a piece of pancake-flat, pristine aluminium that is just ¼ millimetre (or 1/100th of an inch) thick, he adjusted the pressure between the two rollers of the English wheel. The upper is the rolling wheel; the lower, the anvil wheel, which is interchangeable depending on the desired shape of the metal. There are four hash marks Loydell’s made with a Sharpie marker on the jackscrew that moves the anvil, or the lower jaw of the wheel. The hash marks indicate preset adjustments to the amount of force applied to the metal. Each pass through the wheel produces striations, or “blows,” to the panel, stretching, thinning, and shaping it.

The idea, Loydell explained, is to pass the piece of metal through, back and forth, applying different pressure on different sections to make the desired shape. Working the metal back and forth feels almost the same as running a vacuum cleaner over a rug; with each stroke forward, you shift the angle to the right or left so that the entire carpet gets cleaned.

My work was slow, and I easily forgot which way I was supposed to be shifting the metal to feed it through the rollers. The metal almost takes on a life of its own as your hands feed it through. “Don’t put too much pressure on it with your hands; that will make a difference in the shape, too,” said Loydell. “I can tell if someone’s leaned on a wing a bit too hard.” The cars on which he works are made of the softest aluminium you can get.

Loydell and I carried the 10-by-10 sheet of metal I worked into the subtle curve of an hors d’oeuvre platter to the buck, a plastic compound model of the DB5 made from computer scans of six original DB5 cars. The buck or jig – the equivalent of a costumer’s dress form – helps Loydell create the correct shape for body panels. He held my panel to the buck to see what contours needed to be accentuated or flattened. When he’s fashioning a component, sometimes he runs the metal through the English wheel to reshape it accordingly. If finesse is needed, smaller tools come in handy.

Loydell opened a drawer full of hammers and shapers with various heads, his initials carved into his tools, “so no apprentices walk off with them,” he joked. An apprenticeship at Works lasts three years, “but even then, they’re not quite ready to do some of the more precise shaping work.” He’s made several custom tools over the years. “This,” he says, holding up one shaped like a small wedge of Gouda, “I made for one car and never used it again. Just waiting for the right spot now.” Loydell is a legacy employee, as his grandfather worked in this same panel room back in the 1950s and ’60s, perhaps on the same cars Loydell restores now.

Other implements of the craft submit the sheetmetal to a more violent treatment, and the aforementioned cautious PR man winced when Loydell showed me to the crimper. “I realise I said it before, but I really mean it with this one,” he said. “Please be careful.” I giggled at him, then took the metal and placed it between the two vertical metal rods that, driven by a large electric motor, smash down on each other with devastating speed and force producing an ear-rattling patter like machine-gun fire. This is the metalworking version of gnashing teeth, I thought, imagining what my finger would look like flattened to a pulp. The various plates that can be fixed to the ends of the rods contour the metal in specific ways to whatever shape you’re going for. I was making the more dramatic slope of the front right-side wing where the headlight goes on a DB5.

As on the wheel, the metal gets fed into the crimper’s pounding yap, but the shaper must maintain a firm grip or it will snatch it from you. If the English wheel is finesse, the crimper is an angry hippopotamus, mashing its way through anything in its chops. It seemed incongruous that such a savage machine could create the graceful shoulder of such an elegant automobile. The final step of my tutelage, cutting out the curve that would be the right wheel arch with massive metal shears, almost sent the PR man into cardiac arrest as jagged raw metal curled its barbed edges perilously close to my fingers.

It wasn’t perfect, but after more than an hour in the panel shop, the flat shiny piece of aluminium Loydell first handed me was starting to look surprisingly like a wing. For a real artisan like Loydell, the front end of a DB5 takes about 220 hours to shape.

I didn’t have 220 hours, much less the years it would take to learn how to do this job properly, so we left my DB5-ish-looking unfinished wing to Loydell – probably for recycling – and moved on.

The light-grey floors throughout Works carry a high shine. The walls are a spotless white and lined with grey Dura-brand industrial cabinetry. If there was a spot of oil anywhere, I didn’t see it. Each tech has his or her own space, and their tools, which they bring themselves, line the drawers like a chef’s mise en place. All technicians wear black trousers and polo shirts with the company logo embroidered over the heart. It is so clean that the place feels surgical.

In a glass-enclosed corner of the facility resides the trim shop, like a life-size museum diorama. Until recently, the team inhabited a dim, cramped, cavelike room in an outer building. Upholsterers and trimmers now sat bathed in light in their fishbowl, where I was put in front of a sewing machine and asked to thread a needle. The sumptuous leather interiors of an Aston Martin are unquestionably part of the cars’ appeal, and I was about to learn how they are crafted from whole cowhides. But first I had to put on my glasses so I could see the hole in the needle.

The machine before me felt more analog and circa-1980s with its many dials and knobs than the cutting-edge, digital-touchscreen kind you’d find about 45 miles northwest at Aston’s main plant in Gaydon, where it moved its modern and mechanised assembly line in 2003.

Sue Turner, a seamstress who has been at Works for 21 years, happily banged a piece of dove-grey leather with a mallet for me to sew, as if preparing a piece of veal for a piccata. “Just making sure the cow’s dead,” she joked.

Modern car seats conceal foams of varying densities under aluminium or composite structures covered in newly engineered fabrics, including high-tech poly-blend cloth, recycled materials, or faux leathers manufactured by massive machines. However, at Works, the job of constructing a car seat recalls the ancient arts of a saddler or cobbler. Carefully vetted pieces of dyed Bridge of Weir leather are hand-cut to patterns that have existed for decades, then sewn with heavy-duty thread to an underlay of muslin. Between those layers, the inside padding, stuffed by hand, creates the shapes and contours of the seatbacks and cushions. If a customer orders contrast stitching, the thread colour of their choice is used on the exposed stitches.

Turner placed the piece of pounded leather in front of me. Were I an actual Aston seamstress, this would become part of a seat cushion for a 1960s-era Aston. A piece of ecru-colored muslin with vertical grid guidelines drawn at approximately 2-inch intervals was placed behind the leather like a document being typed in duplicate. Turner’s banging had produced accordion folds about 2 inches apart in the leather that I would match up to the gridlines on the muslin. I was to run both through the sewing machine along each fold in the leather, attaching it to the muslin and creating around a 2-inch tubelike channel between the two in which to insert the wadding of the seat cushion.

It took me a minute or two to master working the electric foot pedal. The operator’s heel raises and lowers the machine’s foot, securing the fabric in place, then the toe works the pedal to move the needle up and down, marrying thread from the upper spool with that in the bobbin below for the complete stitch. Even in the trim shop of Aston Martin, your heel-and-toe technique matters. Indeed, there’s a cadence to sewing not unlike working a throttle. Too much and your thread and bobbin can get out of control quickly. Too little and you’ll be holding up the rest of the team after you.

“I used to be that slow, too,” Turner said, watching me, and I chuckled at and appreciated her British candour. As I repeated the process four or five times, proudly increasing my speed with each puffed channel sewn, the likes of a DB5 seat bottom started taking shape.

Turner doesn’t always sew with a machine. Sometimes she does finishing touches by hand. I asked her if she has a signature, some design or initial she puts into her work to stamp it. “I don’t personally, but there was one fellow here who did, as his father did before him. One time he was working on a car, redoing a seat, and came across his father’s work. They’d both ended up working on the same car.” At Works, such bridges across time and generations are not uncommon.

From the sewing machine, I took my semi-decently sewn seat cushion and carried it to the table where I was to stuff it. Padding a seat, I’m told, isn’t a haphazard affair. The padding, or wadding, looks like what’s inside your couch pillows, has about a 1-inch “loft,” or thickness, and the rough texture of a cat’s tongue. The amount can change your driving experience, according to Spires. “Too much padding and you’re sitting higher in the seat,” he said. “You’re too close to the steering wheel and don’t have the right feel in the seat of your pants. We insist that all cars that come through this shop are as the engineers originally intended. The details are critical.”

Inserting padding into a seat-cover channel might sound easy, but it’s more akin to squeezing on tight leather pants when you’ve just put lotion on your legs. It requires muscle. Simon Holmes, a 21-year Works veteran, and Rocco Garofalo, with 12 years on the job, showed me how to fold a long strip of wadding over a flat metal rod the perfect width of the channels I’d sewn into the cushion. A leather strap folds over the entirety of that setup to help smooth the way of the coarse wadding into the equally rough inside texture of the leather of my seat cushion

There was gritting of teeth, and I almost impaled myself in the stomach before getting the wadding in properly. Once in, the metal rod and leather strap were removed. A final pull on the muslin and leather stretched it out properly. I repeated that a couple of times and held up my work to Holmes and Garofalo, seeking their approval. I took the, “Not bad for your first time,” they offered and scurried off, but not before Holmes handed me an embroidered DB6 patch for my efforts.

At Aston Martin Works, a frame-off restoration costs a flat-rate £400,000 (about $548,000) plus tax. After the car gets stripped to its bare chassis, trued, and repaired, the body is put back on and removed twice more, once for powder-coating, then for proper alignment to drill out badge and bumper holes before it goes to paint. Spires counts access to all of the original build books and manuals a key part in the two-year restoration process.

Once back on the chassis, a car will spend 250 hours in the Works paint shop being “flatted,” or sanded, and polished. Any unseemly orange peel gets a good sanding so the owner is left with a shine that looks as though the paint were poured onto their car like tempered chocolate on a cake. Aston Martin Works can colour-match any car to the perfect shade of cerise or chartreuse. When asked if he’s ever persuaded a client to change questionable tastes, Spires, the consummate businessman, responded without faltering: “All that means is when the next owner buys it, the car will be back here to have more work done.”

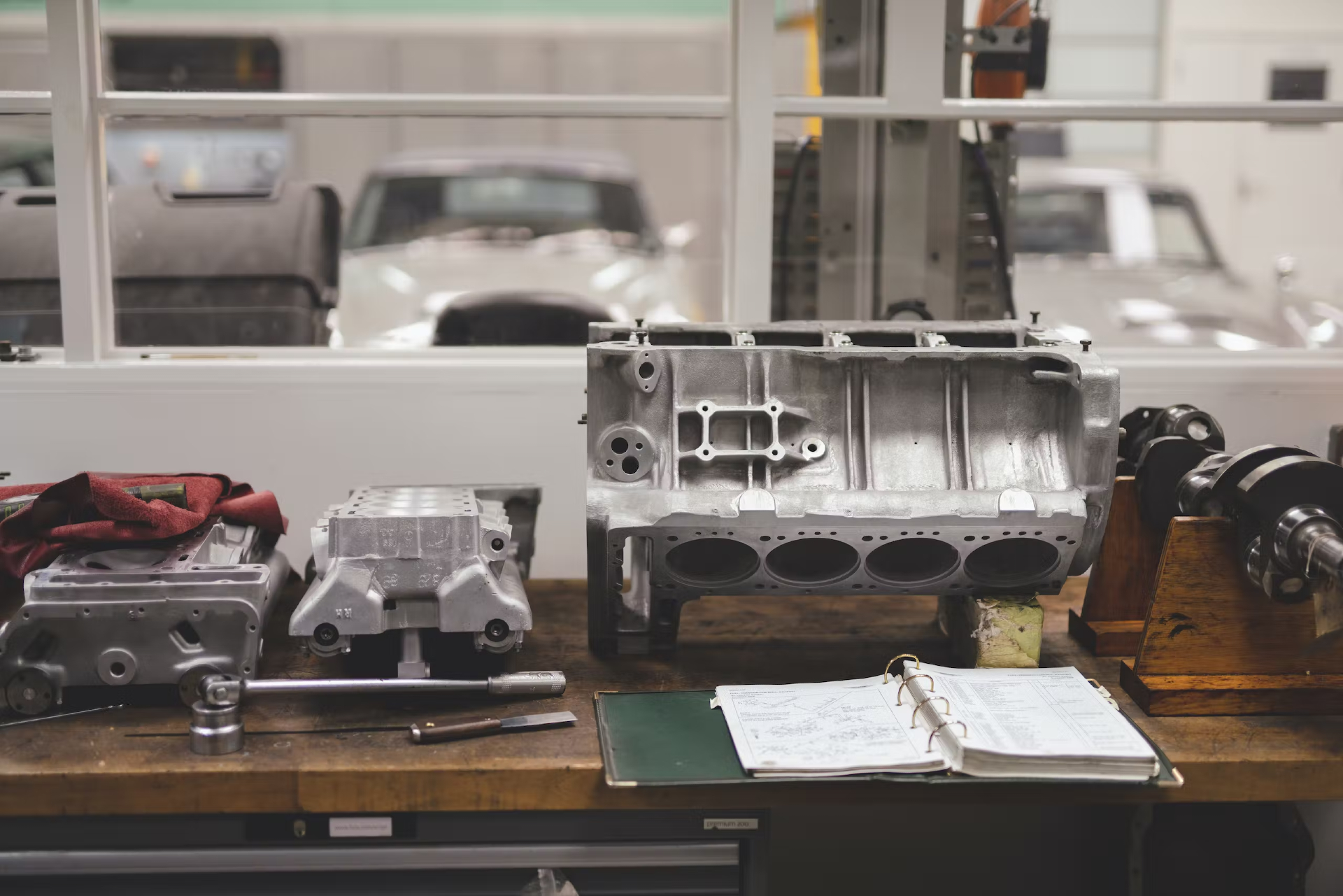

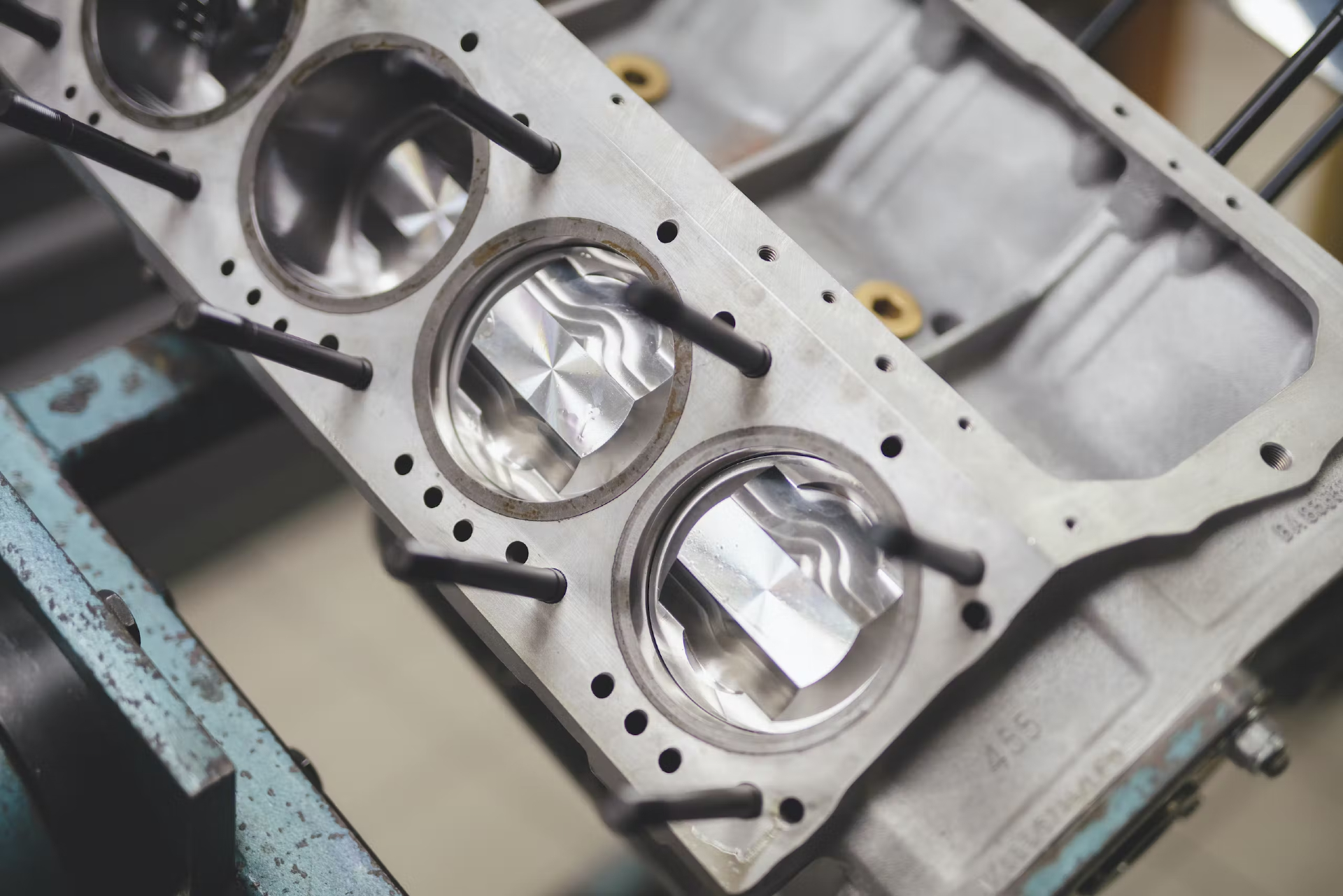

I was ushered into the engine room to meet Tony Young, who’s been elbow-deep in the engines that power Astons for over two decades. He showed me a 5.3-litre V8 that’s getting the POW-spec treatment. The confusion must have read on my face. “Prince of Wales,” Spires explained, which made infinitely more sense than what I’d imagined.

As Aston Martin did with a car made for the then Prince Charles back in the late 1980s, Young is converting this formerly fuel-injected engine into a four-carburettor version. Only 27 of the POW-spec Vantage were made, with the highest output engine possible but normal bodywork. But any customer with any Vantage can transport it to Works and have that conversion done. And that is the case for any Aston Martin. If you want it and are willing to pay for it, you can have it done. “By having the work done here, its provenance is assured,” Spires said. “And while it’s not an original car, it’s done and certified by us, so it’s legitimate.” As there are so few cars, of which provenance is well known, Spires can easily spot a seller pulling a fast one.

If there’s a part Young needs, he can head to the parts department, home to over two million of them. If it’s one that no longer exists, such as the vacuum container on this newly carbureted POW V-8, he can walk over to the guys in the panel shop and ask for one to be made.

For its services, Aston Martin Works will collect your car, whether in-country or from your Bond-esque desert oasis or snowy ski chalet. The discreet folks at Works have circumvented more than one international incident by sending technicians to an owner’s car in undisclosed locations to change some sand-clogged spark plugs or purge an engine running rough on dubious fuel.

In modern car-manufacturing terms, it might be easy to dismiss Aston Martin Works’ use of old-world guild knowledge and Industrial Revolution–era techniques. But Works possesses something that no newly launched robotic car company can buy: history. Aston Martin’s century-long survival has been a hard-fought victory, now delivered in part by the callused hands of the craftspeople inside the factory’s Victorian-era brick walls, using the methods of ghosts.

Read more

Making history with Crosthwaite & Gardiner

Garage door preservation society

Meet the cast of Grainger & Worrall, making engine parts for Bentley, Bugatti and Porsche