An engine puts the motor into the car. Without one, you merely have a carriage and have successfully stepped back in time by 120 years.

During that century and a bit of engine development, there has been a vast array of solutions to the challenge of perfecting internal combustion.

Virtually every person who has set their mind to building a car or motorbike has experimented with the number, orientation, and even shape of the cylinders.

The best designs rose to the top of the heap, but that heap is hardly small. We thought it might be fun to shine a light (not the engine warning light… ) on a few of the more unusual designs that manufacturers sent out into the wild under the bonnets and beneath the fairings of production models.

Tatra air-cooled V8

In the record books of doing something before it was cool, Tatra has a place among the greats. It was only 1937 when it built a streamlined, rear-engine, V-8-powered car that competed in endurance racing, and the three-litre V-8 under the sloping tail was quite something.

It was air-cooled and featured hemispherical combustion chambers. Power output was 75 hp, which rivalled the contemporary Ford Flathead V-8. The Czechoslovakian automaker thought it had a winning formula with the design and continued producing a version of the V8 throughout 1975. The final iteration produced 166 hp—more than a Chevrolet Corvette of the same period.

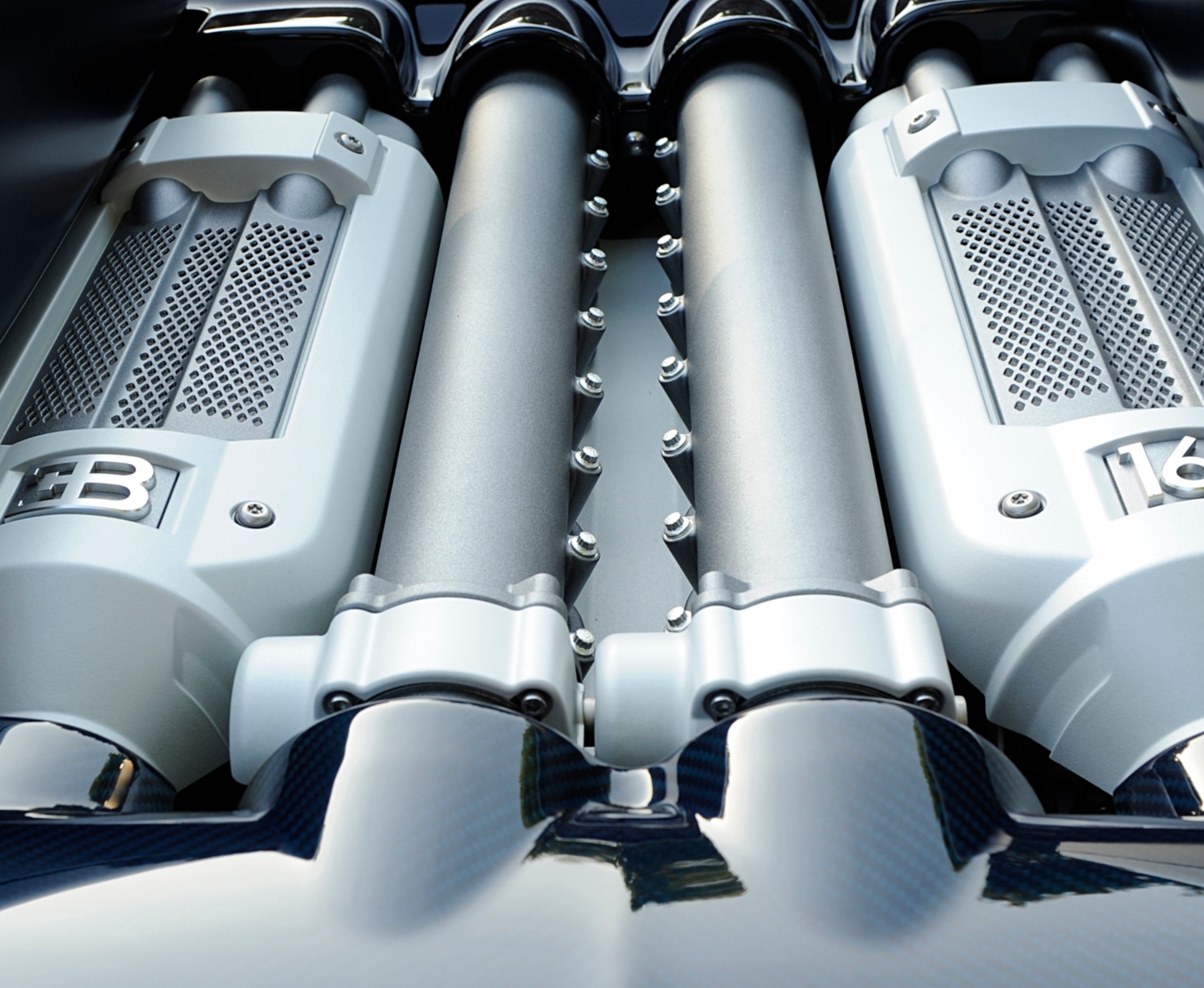

Bugatti W16

In a world flush with what I like to call “numbers cars” – automobiles that seem to exist solely to give wealthy drivers bragging rights – 15 years ago the Bugatti Veyron took things to the extreme. It took just about every number associated with a performance engine and doubled it, or multiplied it by 16, if you want to talk about heat exchangers.

If eight cylinders in a V is good, why not make it 16 cylinders and a W? Seeing the bare block of the W-16 engine is a confusing moment if you aren’t familiar with how the packaging works. The goal is to fit the 16 bores into the most compact package possible, which means staggering them so that all sixteen don’t sit on the same centreline. Interestingly, multiple Volkswagen models received narrow-angle VR6 and V5 engines, which are essentially one bank of this W engine with fewer cylinders.

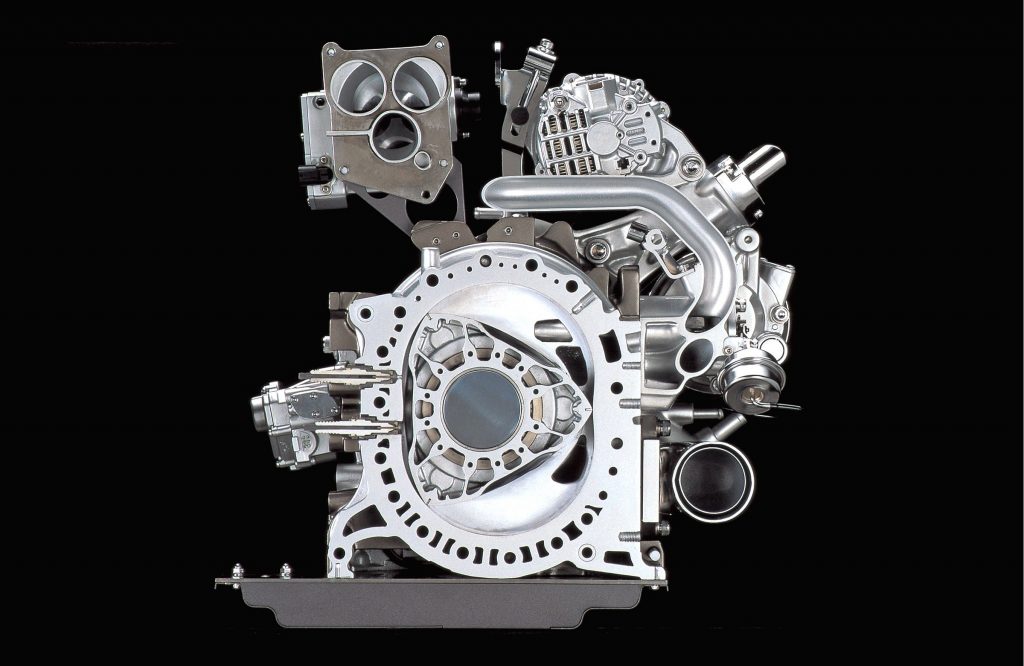

Wankel rotary

The concept of an internal combustion engine requires compression, and the easiest means of achieving that was a reciprocating piston. German engineer Felix Wankel penned a compact design that could fit the four phases of the Otto cycle (intake, compression, combustion, exhaust) into one revolution of the rotor.

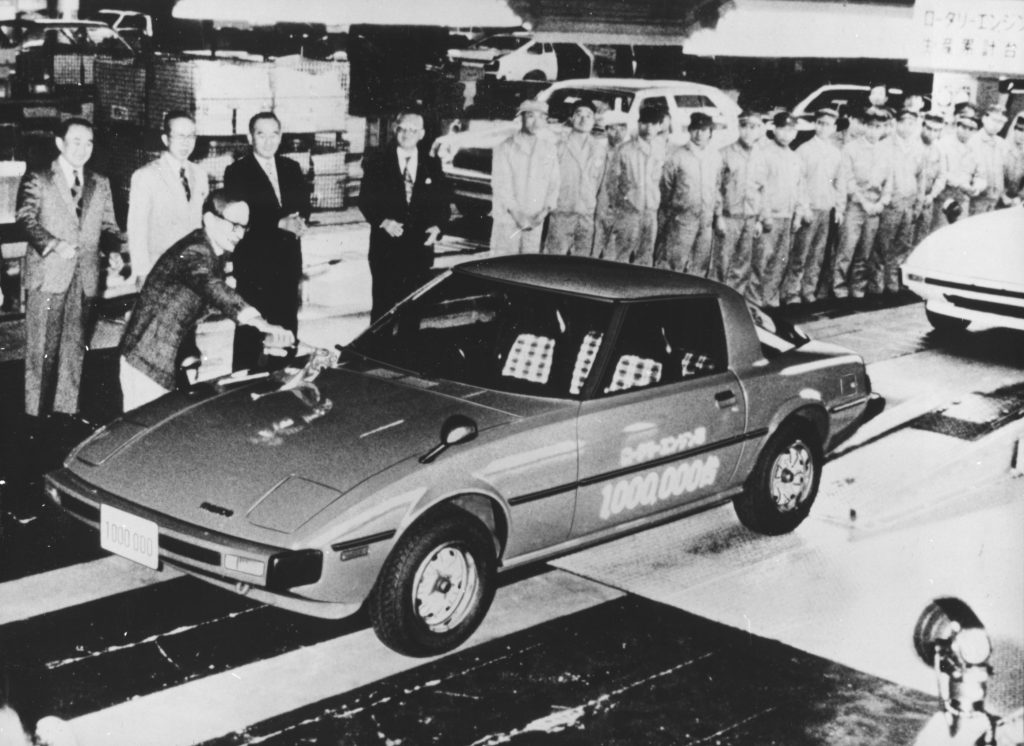

In fact, there are three combustion events for each rotation of the rotor, but the geared output shaft spins at three times the rotor speed. This gives you one combustion cycle per rotor per revolution of the output shaft. Mazda is the manufacturer most closely tied to the rotary design, having installed it in a number of capable sports cars after it acquired the technology, in 1961, notably the RX-7.

There are drawbacks, though. The apex seals at the tip of the Reuleaux triangle rotor have a shorter life expectancy than their piston-ring brethren, and oil consumption is significantly higher than in a reciprocating engine. There are fewer parts to fail – which, on the surface, makes it attractive in an era of long warranties – but the rotary’s thirst for fuel and relatively high emissions makes it a tough sell in the modern market.

Chrysler Turbine

It’s a stretch to call this a production car. However, the fact that Chrysler even considered a turbine power plant for a street car is so absurd it has to be discussed. The plan was simple: shove Chrysler’s fourth-generation gas turbine into a midsize, two-door chassis. It was 1963, and there was really nothing to lose.

The Chrysler turbine team had a lengthy list of upsides to the alternate engine: “Reduced maintenance, longer engine-life expectancy, development potential, 80-percent parts reduction, virtual elimination of tune-ups, no low-temperature starting problems, no warmup period, no antifreeze, instant interior heat in the winter, no stalling because of sudden overloading, negligible oil consumption, low engine weight, no engine vibration, and “cool and clean” exhaust gases” were all cited in period literature.

The reality was that 130 hp and 465 lb-ft put through a three-speed Torqueflite automatic (without a torque converter, because it was not needed) were simply underwhelming and, paired with the cost of production, didn’t stand up to production scrutiny. Chrysler shelved the idea and crushed 46 of the 55 cars produced. Most of the nine survivors are in the care of museums.

Honda V8

Need a reminder that racers in modern times are racing the rulebook, not each other? I give you the Honda NR750. In the early 1990s, Grand Prix racing was dominated by two-stroke engines, but Honda wanted to put a four-stroke on the grid. Specifically, a four-stroke V8 packed into a motorcycle frame. The catch? The rulebook stipulated just four combustion chambers.

So Honda went the unconventional route and blended the eight cylinders together to create four oval cylinders. That makes an engine with a bore x stroke measurement that requires three numbers. The 101.2-mm x 50.6-mm x 42-mm bore and stroke made for a final displacement of 748 cc. Each of the oval pistons is supported by two connecting rods.

It is a shame that the list was dominated by motorcar engines; cast the net wider to commercial vehicles or aircraft and there are some real oddities.

How about the Rootes TS3? A two-stroke diesel with forced induction and six pistons but only three cylinders (the cylinders facing each other and connected to the crankshaft via substantial rocker arms). It was used in Commer lorries, perhaps most famously the Ecurie Eccose racing car transporter.

You could also pick pretty much anything that Napier did; the Lion W12 engine found in Biplanes and the Napier Railton racing car; the Deltic, another opposed piston, compound supercharged, two-stroke diesel most famously found in high-speed railway locomotives; the Sabre, two flat twelves (with sleeve valves, no less), geared together one on top of the other and found in the Hawker Tempest used to chase down V1 flying bombs; the Nomad, which is a Frankenstein’s monster of a thing where a flat-twelve and a gas turbine have been fused together (and a commercial flop that never went into production).