The Honda City wasn’t the only vehicle to which the Japanese automaker strapped a turbocharger in 1982 – that year, it also introduced the CX500 Turbo, and created the first turbocharged production motorcycle in the process.

Honda’s dalliance with turbocharged bikes was short-lived, and after following Honda into the fray, the industry as a whole soon returned to natural aspiration. But in a decade known for excess, the CX500 Turbo, and the CX650 Turbo that replaced it a year later, were remarkably restrained.

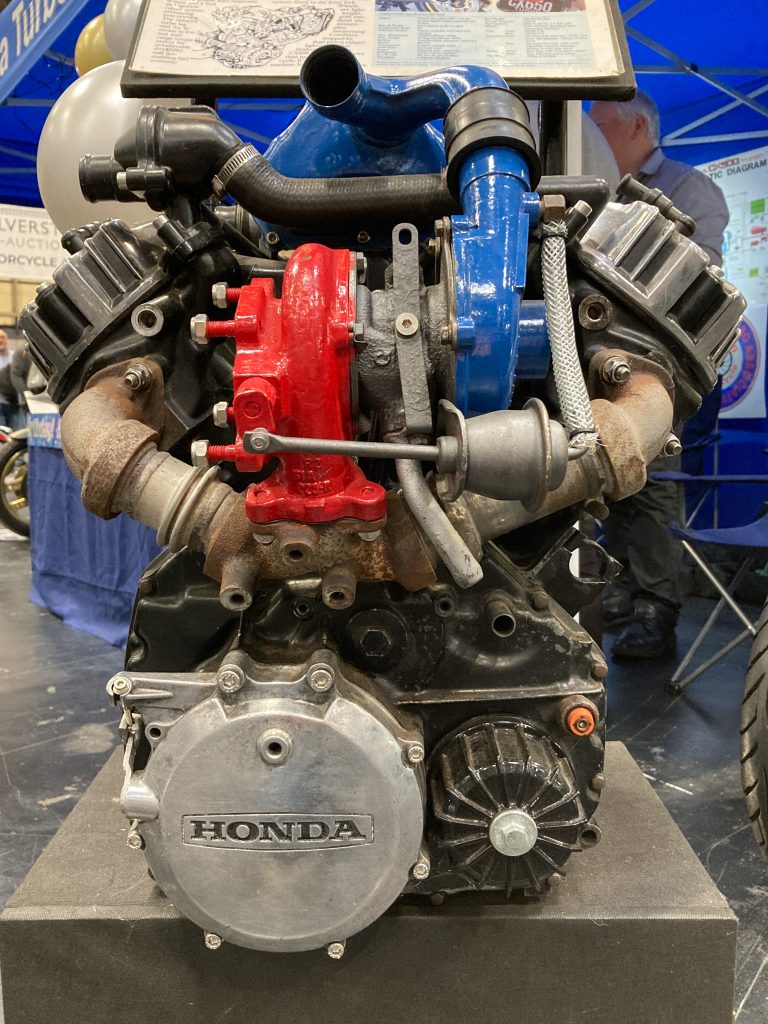

Perhaps surprisingly, this high-performance technology was employed not on a superbike, but a sports tourer. Nor did Honda use an inline four, or even a parallel twin, but a relatively low-tech, pushrod, 80-degree V-twin – though the key to the bike’s docility and reliability was Honda’s programmed fuel injection. The CX500 was Honda’s first bike to use the technology, and it would soon permeate numerous other models across the Honda empire.

“It was built very much for the American market” explains Graham Jones-Ellis, of the UK Honda Turbo Association. “They were sold in the UK, but in much smaller numbers – we think there are only around fifty left, while most of the 650s will be American imports.” It’s thought around 350 Turbos made it to the UK in total – about a tenth that of the US allocation.

While the Turbos might have had American cruising in mind, even in a modest state of tune, they offered a useful performance increase over the original V-twin, the engine jumping from 48 horsepower to 80, with the 650 hitting 99bhp.

“They’re pretty quick” says Jones-Ellis. “Obviously you’ve got all the restrictions of 1982 brakes, and 1982 suspension. But they’re still great fun to ride.”

This duality of purpose was confusing to the press,. Critics couldn’t decide whether it was a sports bike, given its performance potential, or a tourer, with its larger frame, tall fairing and shaft drive.

The waters were muddied further since while factory turbocharging was in its infancy, the aftermarket had already taken a lead in this area, boosting bikes to significant power figures but with rather less concern for rideability.

“Most of the aftermarket kits were far too big for the bikes, and on big engines too, like 1100ccs” recalls Jones-Ellis. “You’d have an absolute monster in a straight line, but they were almost impossible to ride. Whereas Honda wanted the bikes to actually perform – so they tried to get the most out of a small engine, and a small turbo. These bikes produce a huge amount of torque at very low revs, and that’s the real difference. The torque curve is very flat.”

Response was good too, the small engine running a reasonable 7.2:1 compression ratio (8:1 for the CX650), and short exhaust runners ensuring the turbo spools up quickly. Response isn’t quite on a par with a naturally-aspirated bike, but as Jones-Ellis says, “it’s certainly not bad.”

The other Japanese brands didn’t quite follow Honda’s lead with their own bikes, however. “They all jumped on the bandwagon – Kawasaki was the last to drop turbocharging, but the Suzuki and the Yamaha were more like add-ons. It’s probably a little unfair, but they weren’t very well engineered…”

Expensive to make and often unreliable, Jones reckons these subsequent bikes somewhat soured the market for turbocharged motorcycles, and burst the brief bubble – while offering few tangible benefits over a conventional bike. Honda’s step into the relative unknown was rewarded with just two years of sales – one for the CX500, and another for the CX650.

Jones-Ellis had no particular interest in the bikes originally, but after joining the club after hanging around at meets with friends, he took the plunge – and now his CX500 is a keeper.

“It’s been extremely reliable” he says, having recently proved it with a visit to Norway on the bike. “There are a couple of very minor faults that are easy to fix, and a lot of the parts are still available. They’ve got these old computer-controlled electronics in them, and it’s like the size of a small novel – but most of these bikes have still got their original computers, and even their original turbos in them.”

In fact, aside from wiring slowly degrading over time, it seems like Honda’s first dabble in motorcycle turbocharging is no more troublesome than an old Super Cub. The injection helps, giving the CXs an advantage over the carburetted Suzukis and Yamahas, and as high-quality bikes in period, the brakes and suspension are also good – for their day, at least.

It’s a mark of how much owners enjoy the bikes that Jones-Ellis reckons several club members have more than one stashed away. Perhaps it’s really a CX500 or CX650 Turbo, rather than a Motocompo portable bike, that would be the perfect complement to a Honda City Turbo in an enthusiast’s garage…

Read more

The Honda Gold Wing was flawed, but also distinctly special

Superbike, super price: Honda RC30 sells for £65k

Kawasaki’s KR-1 was a fickle failure… but fantastic fun