Serendipity dropped this rare 1972 Ducati factory racer into my life 29 years ago. Here’s how it changed me.

In the The Chronicles of Narnia, protagonist Lucy innocently enters a world filled with mystical characters and intrigue. In the real world, though, such wonderment never just happens . . . or does it? From a motorcycling perspective, just such a miracle occurred for me in 1995 with the chance acquisition of this Ducati works race bike, one of eight built for the 1972 Imola 200 in Italy. Ownership (including trying to sell it) has been one of duty and fidelity, care and commitment, with some incredible life experiences thrown in. And oh, yeah, stress.

The Machine That Made Ducati

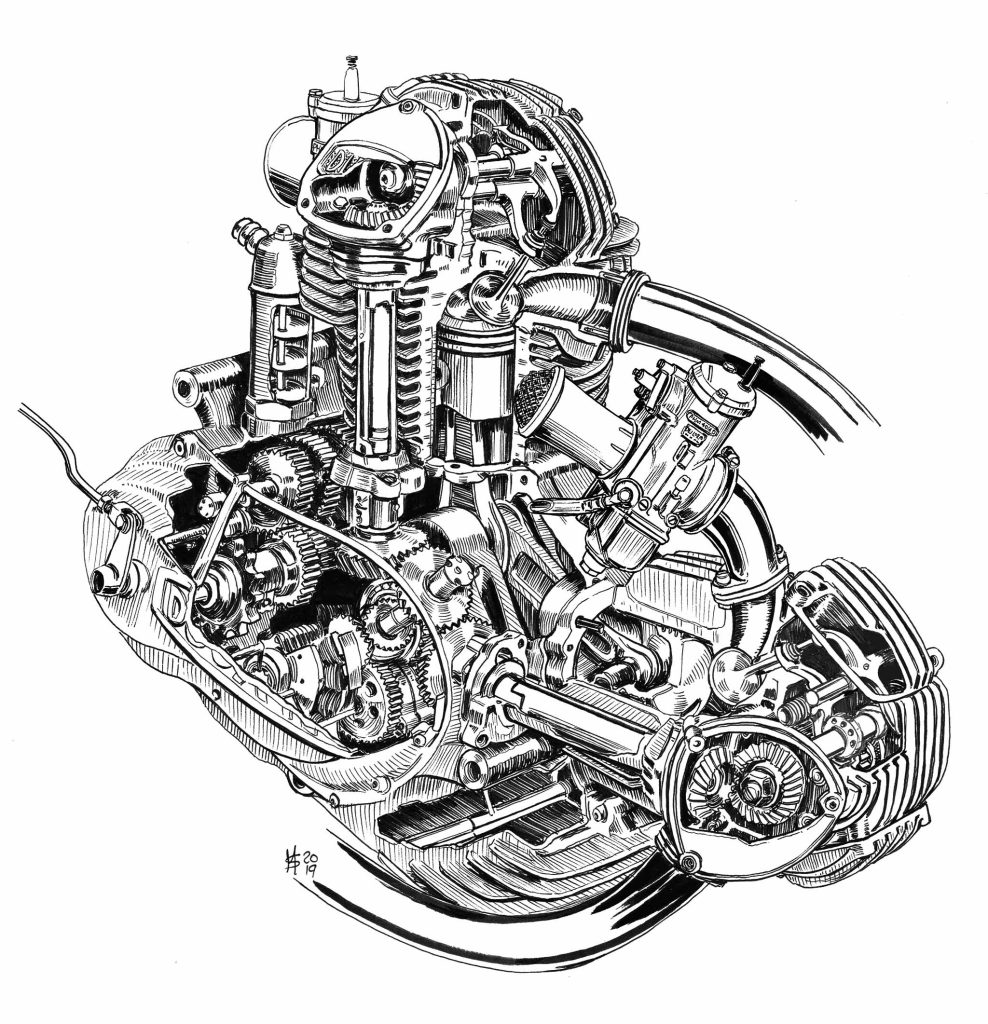

Ducati’s Imola racers stemmed from the new 750 GT, a road-going 750cc V-twin of exquisite engineering and design. Exotic, torquey, and stylish, the 1972 GT was definitively the Gran Turismo of road bikes. Its air-cooled engine boasted aluminium construction with overhead camshafts driven by elegant tower shafts – no chains, belts or pushrods – and a unitised five-speed gearbox. Akin to a Vanwall Grand Prix car or early Porsche Carrera, the gear-driven cams were a 1950s throwback chucked forward to the 1970s – an amalgam of old and new, elegant and expensive, that could not last forever. In short, the gears made too much noise, the build cost was prohibitive, and servicing was highly technical.

Even so, within two years, Ducati’s 750 V-twin range expanded to include the GT, the racy yellow Sport, the exclusive desmodromic Super Sport, and the factory Imola racers. Arguably, the lineup mirrored Ferrari’s vaunted 250 series: e.g., the Ducati 750 GT and Ferrari 250 GT; the 750 Sport and 250 GTL Lusso; the 750 Super Sport and 250 GT SWB; the 750 Imola and the 250 GTO. Except Ducati built only a handful of Imola racers to Ferrari’s 36 GTOs. Translation: Ungodly rare.

A Random Call

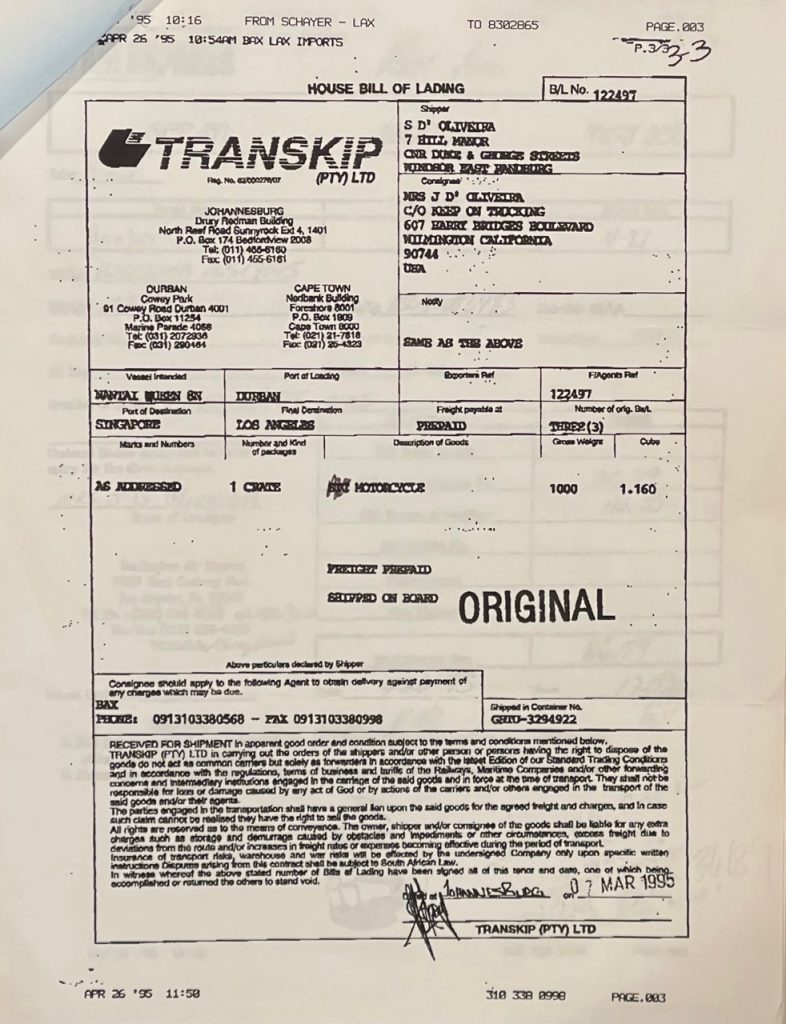

The Ducati’s seller was Michael D’Oliveira, the CFO of a trucking company. He called on a typical fall day. We were not acquainted, but he’d received my number from friend and marque expert Phil Schilling, who told him, “Call this guy, he likes old Ducatis.” I hadn’t solicited the call, but when I answered the phone in my downtown Santa Barbara office, the young man introduced himself and explained that his father, John D’Oliveira, had bought the Ducati in Johannesburg, South Africa, in 1976, and after his passing in ’86, the family sat on Dad’s bike collection for another decade before deciding to sell. Michael and his wife then arranged to export the Ducati to SoCal, where he lived, as a test case.

Michael explained that the machine was supposedly Paul Smart’s bike. I was quizzical, because period reports (no Google then) were that Smart had been gifted his winning bike after Imola, and that it lived with him in England. We discussed a price anyway, and that evening I scoured my few Ducati books to learn about the machines, which were essentially unknown here. For instance, they had desmodromic valvetrains, unique high-low dual exhausts, triple disc brakes with slotted front rotors, and oversize fuel tanks. Piquing my interest was a book passage recounting where the works bikes went following Imola: Australia, England, Canada, Greece . . . and one machine dispatched to South Africa. Could it be?

Meeting a Masterpiece

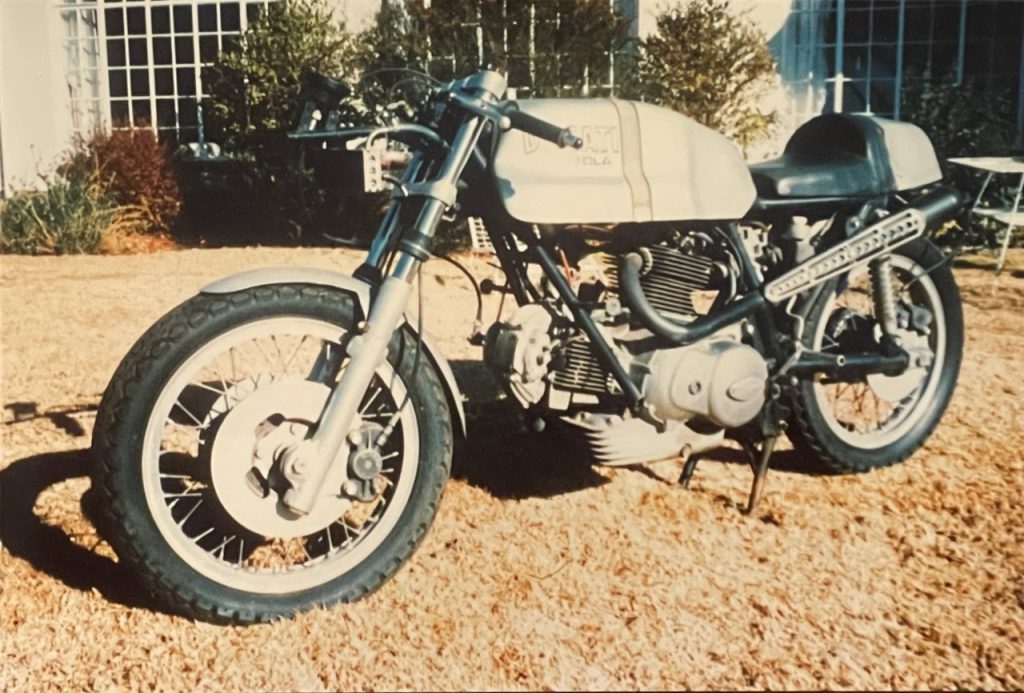

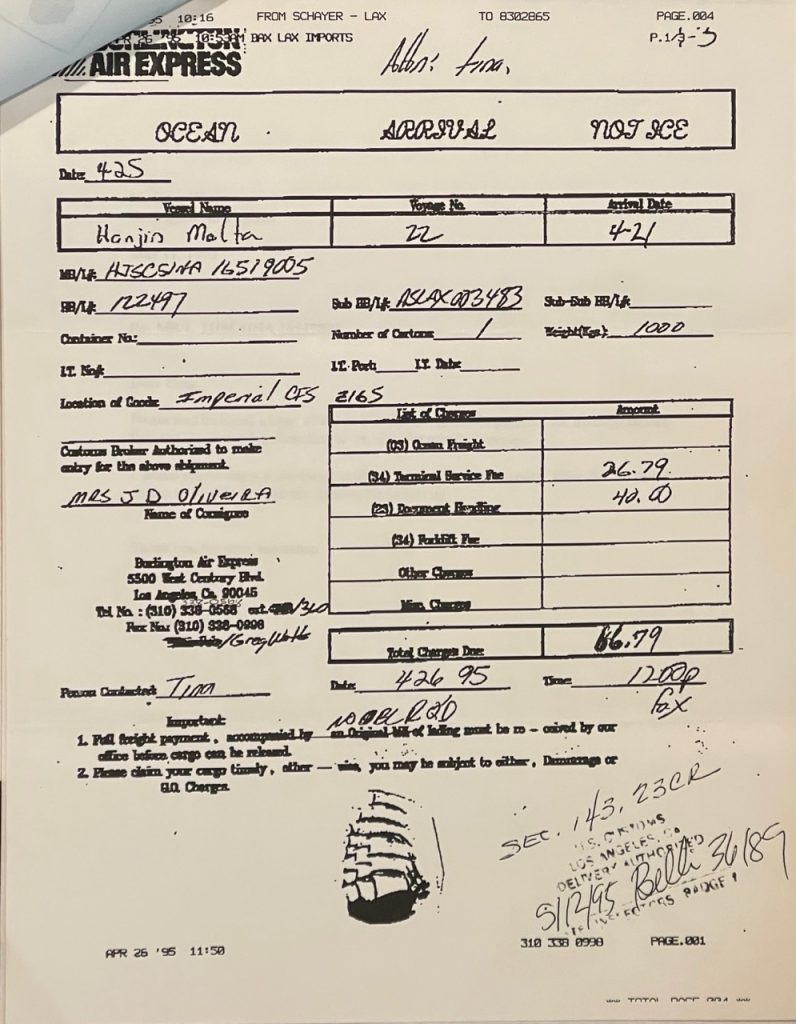

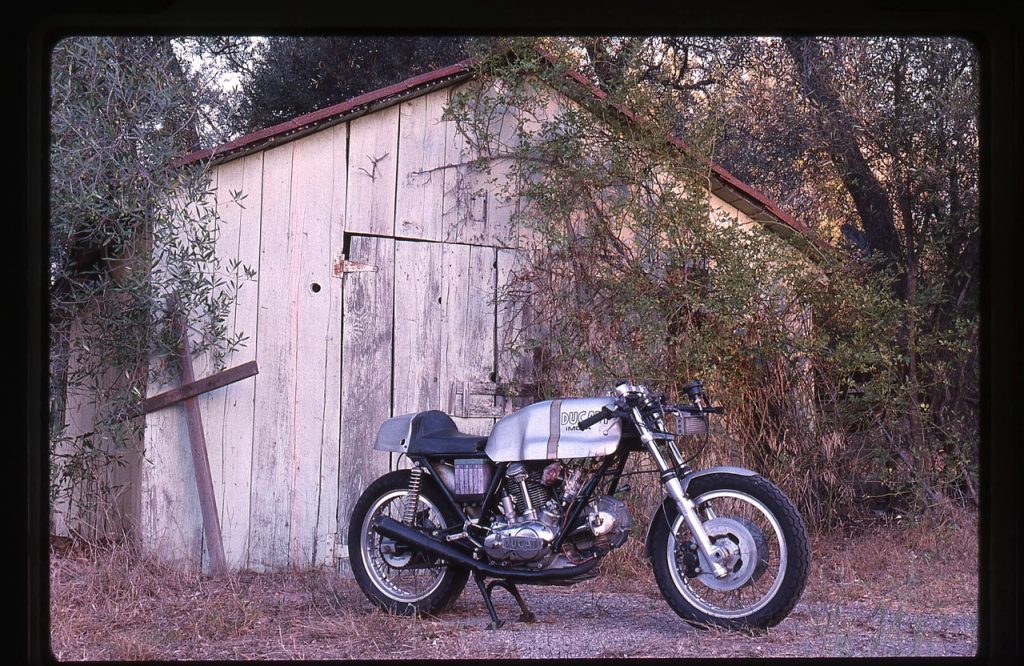

While I knew little about the Imola bikes (few Americans did, as they weren’t campaigned here), I understood how fleeting opportunity can be. So the next morning I left for Wilmington, California, with Siata 8V restoration expert Tony Krivanek in tow. We found the Ducati alone in a gritty warehouse, its home since being released by U.S. Customs following its journey from Durban to Los Angeles Harbor aboard the 951-foot freighter Hanjin Malta, a monthlong ordeal in the spring of ’95.

En route, the ship had navigated the Cape of Good Hope, the South Atlantic, and the Panama Canal, then steamed past Costa Rica and Mexico before offloading in L.A. Free of its shipping crate, the motorcycle was dusty and grungy from decades of disuse. But its bones looked right. It had the correct brake rotors and the exhausts appeared authentic, with the low-slung righthand pipe scraped flat from dragging on the track during hard cornering. The oversize fibreglass fuel cell had a crudely enlarged filler opening. And the original remote oil cooler, Veglia racing tach, solo seat, and Ceriani racing shocks were all present. This appeared to be the real deal, the bike in the history books.

One detail still needed verifying, however – the desmodromic valvetrain. Popularised by Mercedes-Benz’s W196 and 300SLR racers of the 1950s, desmo systems forego valve springs in lieu of secondary camshaft lobes and inverted rockers that manually pull the valves closed. This eliminates the possibility of valve float and spring breakage, historical banes of high-speed engines. Genius. Ducati’s precious Imola bikes were the first V-twins to incorporate this technology, which the company still uses today.

Obviously, I had to know: Was this really one of them? Thinking ahead, I’d brought a 5mm Allen key for removing rocker covers. Inside the weathered front head I saw them – gleaming hard-chromed and polished desmodromic rocker arms. This, together with more Imola details such as dual-plug ignition and huge 40mm Dell’Orto pumper carbs, convinced me this was the racer dispatched to South Africa in early 1973. I was 100 percent sold, so I paid up and rushed to a nearby U-Haul for a box van while Tony guarded the bike. The gas tank rode on the truck seat beside me on the way home, a reminder that what was happening was real. I stopped at Phil Schilling’s house en route. He climbed into the truck, sat on the inner fender, and had a long, quiet look at the bike. He’d been at Imola and saw the machines being assembled at the factory beforehand. “Oh, shit,” he whispered.

Mystery and History

If you discover a gold vein somewhere, that’s only the beginning of the work required to strike it rich. Except exploring history, not riches, was the reward for adopting the Ducati Imola bike. Although the lucky acquisition was one thing, researching its past, carefully returning it to period-correct condition, and becoming an active custodian were different matters entirely. I began by calling Paul Smart at his Kawasaki dealership in Kent, England. His Imola winner was displayed there and he was kind enough to report its frame and engine numbers. That was the beginning of our friendship and a research quest that continues three decades later.

On my lunch breaks I’d sometimes visit nearby bookstores to peruse the Transportation section for motorcycle history books and European classic bike magazines, hoping to find anything on the Imola racers. Occasionally there’d be a writeup and photos about either the “Spaggiari bike” (Smart’s Italian teammate, Bruno Spaggiari) or else Smart’s race winner. But never any others. Digging deeper was required.

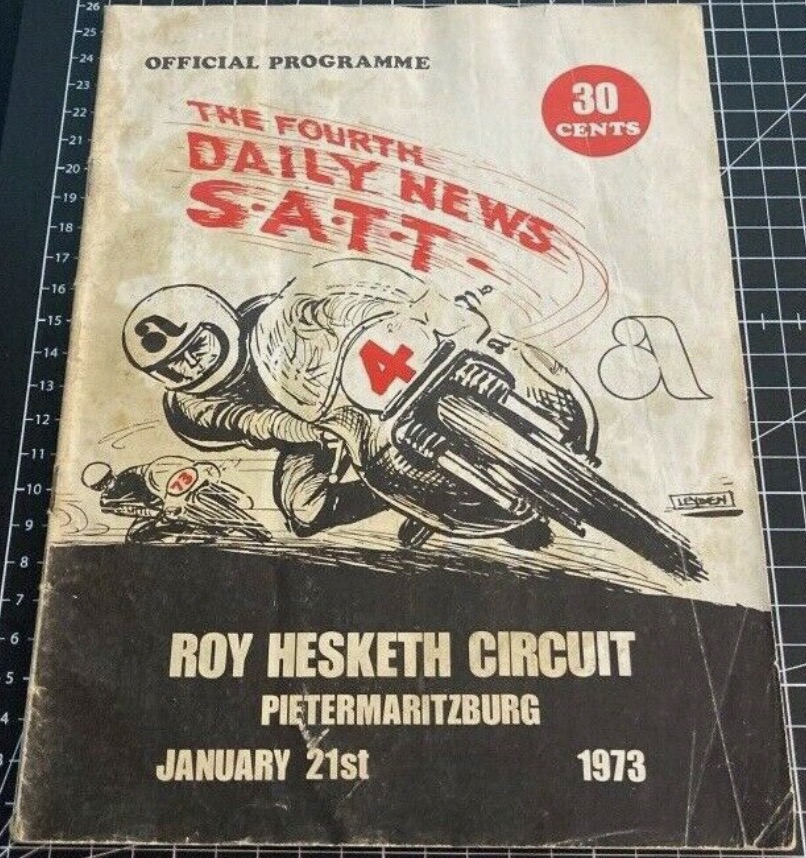

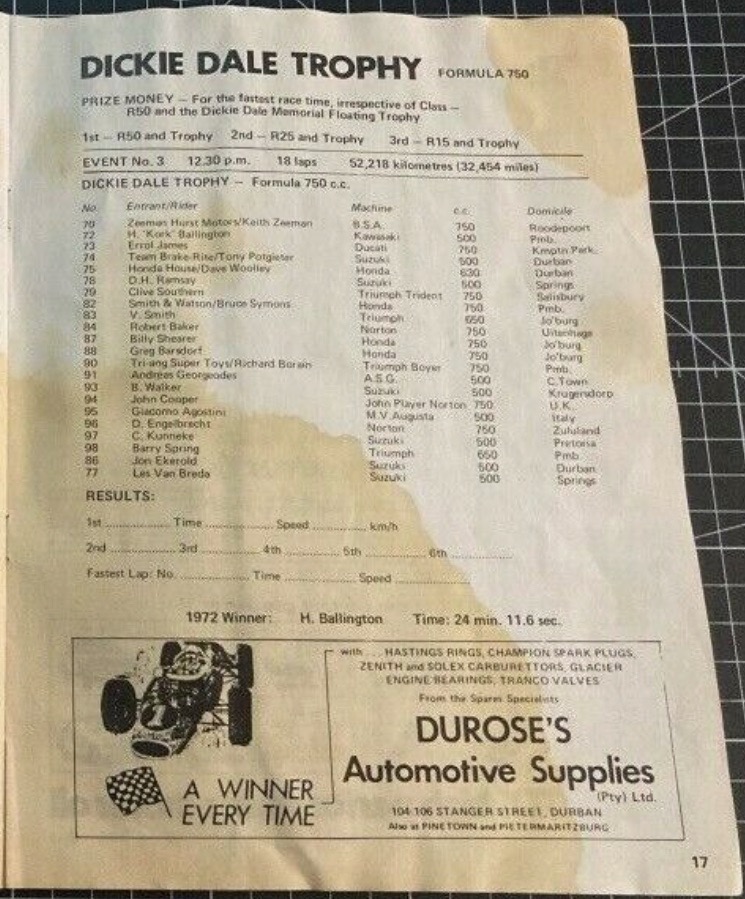

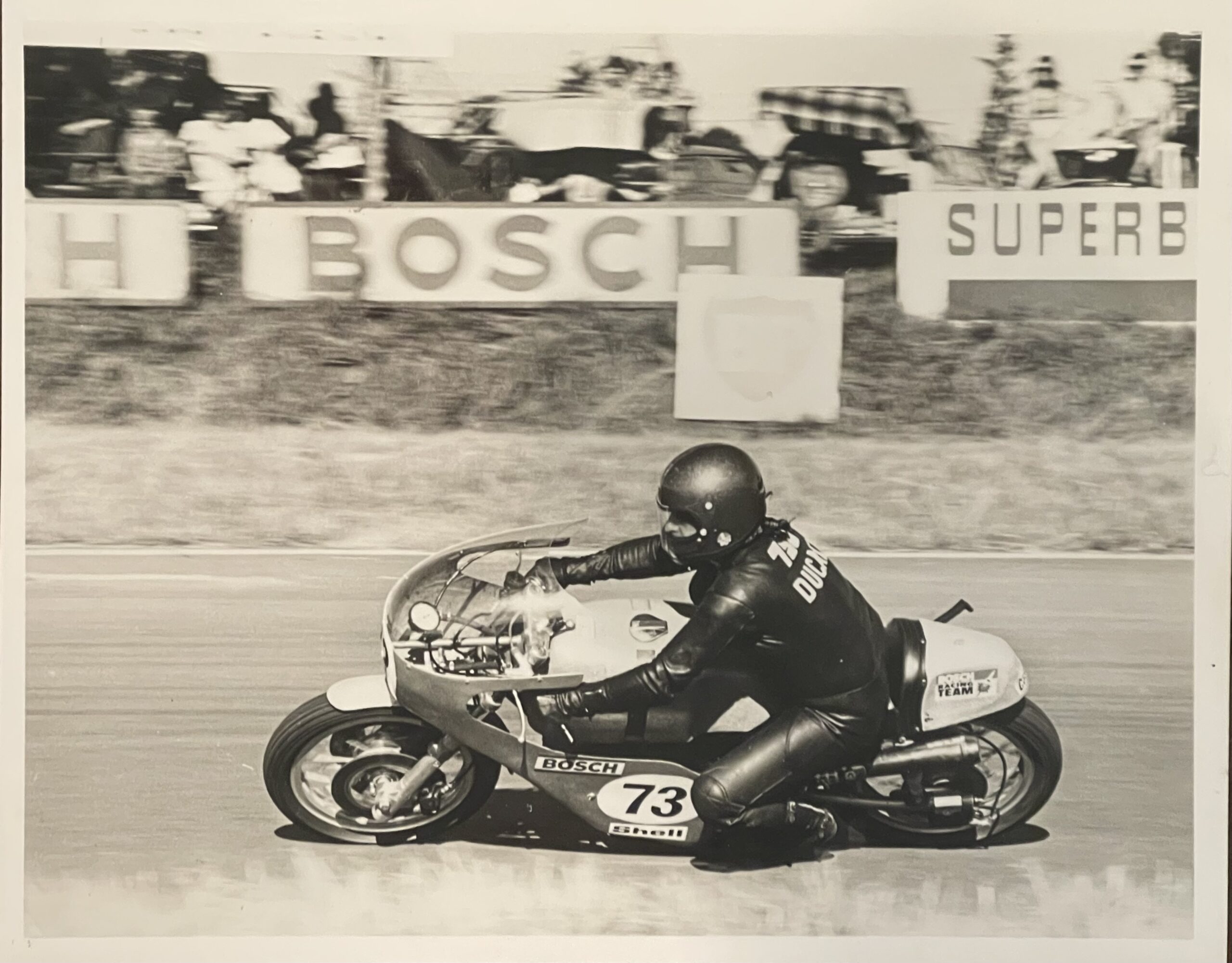

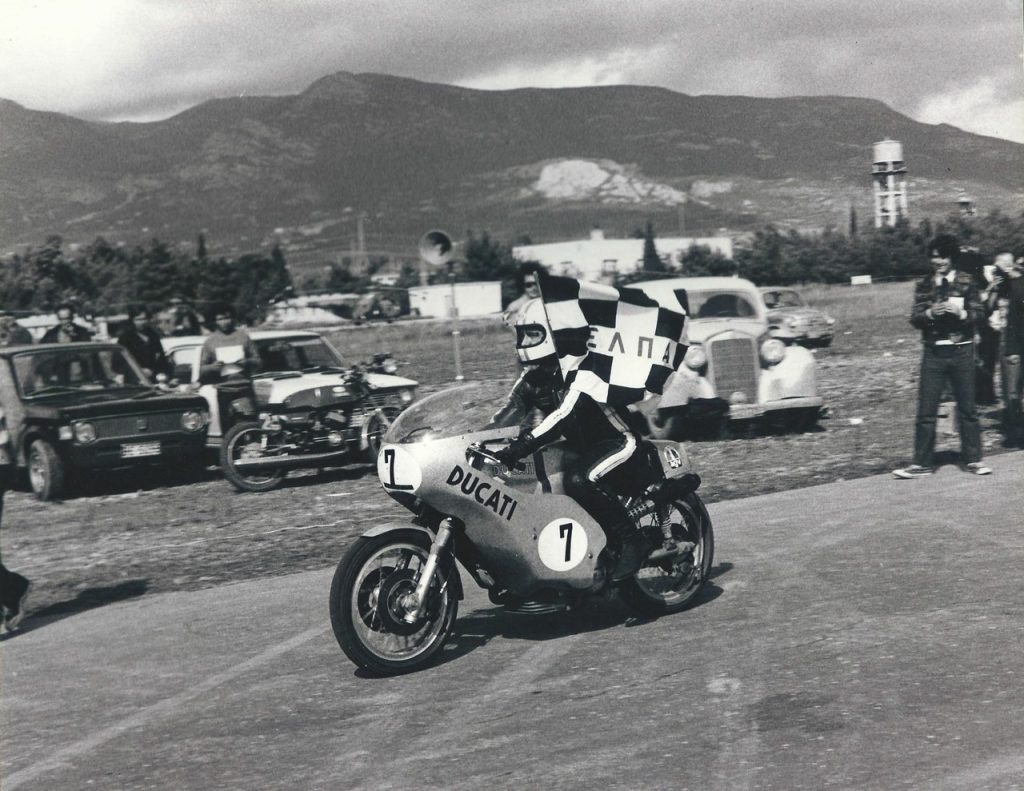

Calling, faxing, and then emailing South Africa was pivotal to understanding this motorcycle’s history. Crucial were Errol James, who raced it in the South African TT at Roy Hesketh Circuit on January 21, 1973, against Giacomo Agostini, Mick Grant, and others, and photographer R.K. Edwards, who photographed the event. I reached James for an interview and Edwards mailed some 8×10 glossies of James racing the Ducati, irrefutable evidence this motorcycle was in South Africa at the time. Further, John D’Oliveira’s family provided a period telex sent by the Ducati factory to Vetsak, the importer, regarding cam timing, and government forms showed he had purchased the motorcycle on May 4, 1976. (Years later, Australian expert Ian Falloon filled in other holes. He reported that while this chassis didn’t compete at Imola, later in 1972, across the Adriatic Sea in Corfu, Smart rode it to victory in the Grand Prix of Greece, his final win on a works Ducati. Not long afterwards, it crossed the equator.)

In South Africa, scrappy James was a charger on the racing scene and led the 35-lap TT outright before finishing fifth. Next, the Johannesburg rider contested a dozen events in the national Formula 750 series; winning some, he ultimately finished second in the championship. The bike’s final race was in Rhodesia, where a con-rod bearing packed up. No spares meant the bike’s failure was also its salvation, because instead of being raced to eventual destruction, the Imola racer sat until Mr. D’Oliveira purchased it.

Risk for Reward

This safety net of indolence was about to tear, however. As a raving Ducati fan, a history buff, a racer, and an enquiring mind, I sought to care for this bike not by restoring it, but rather by preserving and experiencing it as it was in the day, cost no object. And like a physician, above all I pledged to “do no harm.” This included not crashing on the track, which is where I anticipated getting to know the Imola bike while sharing it with others.

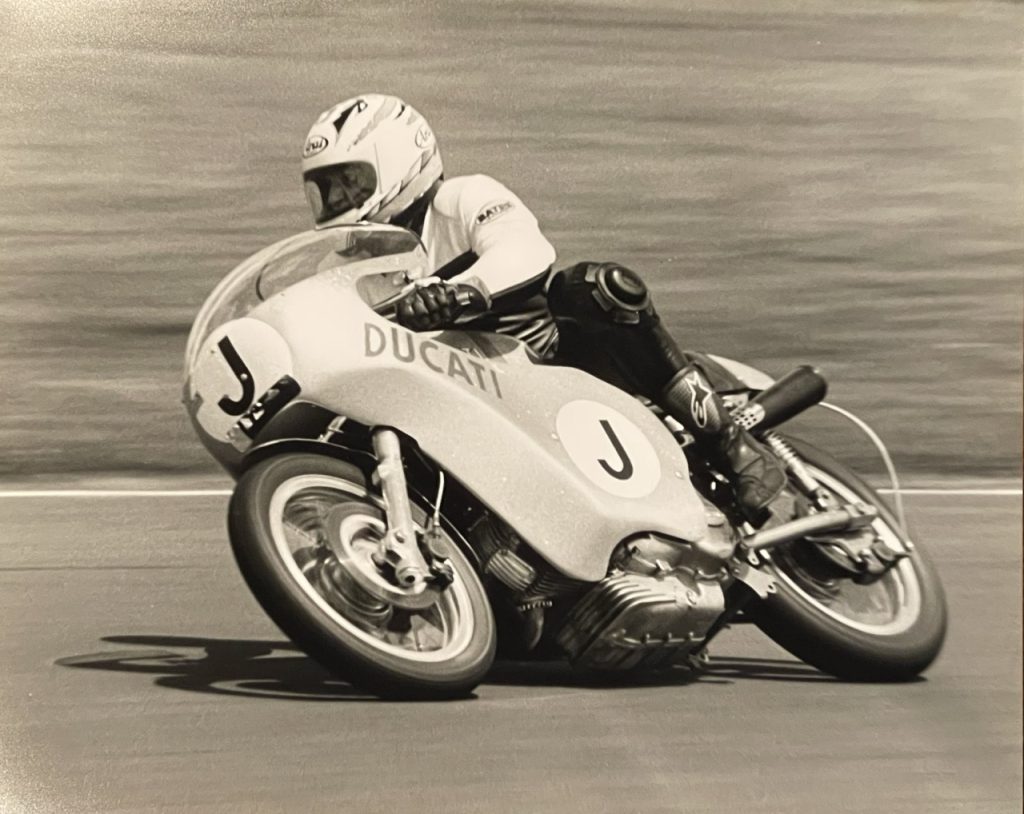

Understanding that the jewel-like engine, brimming with hand-shimmed gears and valvetrain, needed top-flight setup, after sorting out the chassis and bodywork, I air-freighted the machine to McIntosh Racing in New Zealand, a world authority on such motors. In a few months, they rebuilt the V-twin and installed a new competition-spec chain, brake lines, tyres, and more. In February 2000, I flew to Auckland with helmet and leathers to participate in the Pukekohe Classic Festival, among the world’s best vintage racing events. The Ducati hadn’t seen a track in over a quarter century.

It did not disappoint. The Imola proved effortlessly fast, surprisingly smooth, completely unfussy, and possessed a terrific clutch, gearbox, and brakes (among motorcycling’s first triple-disc setups), plus handling as stable as a locomotive. As I crouched behind the fairing, the open exhausts became background noise. More prevalent were the seething intakes, gasping like demons below my chest; two-dozen gears whirring inside the alloy cases and air rushing over, under, and around.

The Ducati’s only fault was being hard to turn quickly, thanks to its long wheelbase and relaxed steering angle. Knowing the motorcycle was historically important, I sought to ride fast, but absolutely to not “bin it.” In New Zealand, I won a race, finished second in another, and received my awards from visiting 15-time world champion Agostini, who ironically had been beaten by the same motorcycle in South Africa 27 years before. A Californian in a strange land with a magnetic bike, I was humbled by the attention we garnered, which included one kid who waited all weekend to shyly ask for an autograph. It was a once-in-a-lifetime weekend with keen enthusiasts on the underside of the globe. Spectators loved seeing the Ducati, and stiff competition vetted it and fulfilled my desire to understand the Imola racers, far beyond what an armchair scholar could ever know. Smart was correct when he said the bikes were deceptively fast. After my last race there aboard this bike, I remember telling someone, “That is as fast as I ever want to ride a motorcycle.” (The Imola 750s could reportedly reach 150 to 169 mph.)

The Ducati flew home to California in early 2000, and I picked it up in my little four-cylinder Toyota 4×2. Previously, I’d told friends that my plan wasn’t to continue racing it, but rather to do a couple of track days a year forever. I did that faithfully for a while before relapsing to contest two Laguna Seca races. There, scrapping hard and fast with go-getter riders on their freshly built, non-historic, and perpetually repairable “vintage” bikes reminded me that such racing isn’t always very vintage; it’s guys trying hard to win and taking every advantage afforded by the rules and their budgets. If they crashed and took me down in the process, or if I made a mistake or had a mechanical issue, I’d be screwed, because few spares exist for these bikes, and the original fibreglass with its embedded silver metalflake gelcoat cannot be repaired or replicated. Essentially, any crash would be game over for this highly original bike. Following that weekend, I retired the Imola from competition. As its owner and guardian, the risks no longer made sense.

Alternative Energy

“No racing” didn’t prohibit controlled track use faithful to my original goals, however. In 2007, for an article titled The Holy Trinity, while nursing a broken fibula, I loaded the machine into a pickup and trucked it to Willow Springs for Paul Smart to test alongside Ducati’s 1974 750 Super Sport and 2007 Sport Classic PS1000LE. The Imola also participated in the Monterey Jet Center party, The Quail (both the Motorcycle Gathering and the Motorsports Gathering), various SoCal shows, and the 2011 Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance, when Italian motorcycles were featured. Clearly, having the right machine opened the right doors.

I found these prestigious shows interesting but generally lacking the “action” that feeds my rider/racer mindset. A viable middle ground, though, was the Pebble Beach Tour d’Elegance. Since the Imola bike’s invitation to the Concours was one-time only, I sure wasn’t going to skip the accompanying 70-mile tour. From Bologna to Highway 1’s Bixby Bridge via Greece, South Africa, New Zealand, and the U.S.A., why not? Life is an oddly winding road, even for a race bike.

Donned in my black leathers and shivering in the coastal fog of the early morning, I envied the car drivers and passengers happily lounging in cockpits and cabins as we awaited the 9:30 start. My entire world was the hard-edged Ducati, and draped over the long fibreglass fuel cell, I fretted about whether it might leak race gas all over the engine (it didn’t), and whether the battery/coil ignition would last (it did).

On the tour, I discovered that the Ducati was just viable at 30–60 mph but unfulfilling dynamically. What was fun, though, was piloting a blatantly illegal Formula 750 racer on coastal Highway 1, with law enforcement clearing the way. This was also the year Pebble celebrated the Ferrari 250 GTO, and at one point I found myself between two of them, the lean meat in an £80 million sandwich. Luckily, the bike ran faultlessly.

Ahead of Sunday’s concours, I rode the Ducati onto the field during “Dawn Patrol” at 5:30 a.m. and I was pretty sure that folks in nearby classic cars didn’t like the open exhausts much.

A New Chance

Following Pebble Beach, the Ducati resumed its slumber at home, emerging occasionally for a track session, a magazine or video project, a social function, or a show, including an 18-month stint at the Petersen Automotive Museum, where it headlined the Silver Shotgun exhibition. Then, in early 2024, an email from auction house Gooding & Company arrived, soliciting motorcycles for a springtime online sale. Huh. In truth, I’d mused periodically about whether, since I was done racing the Ducati, it should just move along. Why own brushes, canvas, and an easel if you’re not going to paint?

I’ve always regarded Gooding favourably, and protected by a reserve, I decided to give it a try. It was only my second auction experience as a consignor. I scoured my files for needed documentation and historic photos, and the garage for original take-off parts, then the company sent out a photographer and videographer and put much effort into creating a listing.

Interestingly, what should have been a straightforward, methodical process felt as much of a thrash as preparing for a race weekend, but everything got submitted on time and the online auction period began on May 8. To be honest, I found the two-month preparation period stressful and didn’t enjoy the loss of personal control I felt, especially upon delivering the racer to the company’s showroom before auction. In nearly three decades, except for its New Zealand rehab and the Petersen exhibition, the bike had never been out of my direct control. Insurance sure does ease the mind, though; I recommend it! Soon after the auction went live with an estimate of $650,000–$750,000 (£518,000–£598,000), the media/blogger-sphere spun a thread that the Imola could be the first million-dollar motorcycle sold at auction. Clickbait or not, that got my attention. But I wasn’t holding my breath.

To put it bluntly, though, the end was anticlimactic, with the high bid just missing the $650,000 reserve. Auction wags often comment that a no-sale only means the right people weren’t “in the room” at the time. But that’s apparently what occurred in this case. During the 10-day online period, the high bid sporadically increased, and while I didn’t monitor the situation often, friends and family kept me apprised. Although the high bid didn’t get it done, one thing is true: Now that the bike has an esteemed Falloon Report (akin to a Massini Report for Ferraris), thorough documentation, and worldwide exposure, any further sale attempts – if ever, if any – will be easier.

In the meantime, the bike is safely back with me again, and three decades with the Imola 750 have taught me that owning a piece of history is both a privilege and a burden. Either way, it sure looks good in the den.

Best story. Oscar right there.

This is an amazing story , what a bike , a piece of history that you can move and take where you want , joy.