It’s 1972. If you were a teenage boy hanging about in the bus shelter waiting to get home after school, your thoughts might have been on two things: music and motorcycles. It was a rare teenager who didn’t have a part-time job, working his way to saving enough for records, a guitar and a motorcycle, in that order.

Like playing LPs loud enough to blow the speakers of your parents’ Hi-Fi, or rehearsing with the band in a friend’s garage and gigging the local pubs and working men’s clubs, riding a motorcycle was entertainment, escapism and friendship all rolled into one heady mix of leather jackets, open-faced helmets and rollies.

Oh, and it meant a kind of freedom that didn’t involve catching a bus.

In the early Seventies, the bike had to be British. A Triumph, Norton, or BSA was the dream. Big, thumping, hairy-chested twin-cylinder machines like your dad’s or grandad’s. A 650 or 750, of course. It was generally accepted that there was a degree of risk when it came to British bike reliability, but that was part-and-parcel.

You would have had to go through a few cheaper years of life on a lightweight BSA Bantam on the way to that 650 or 750. And, true, there was curiosity about new-fangled Japanese bikes too – but the Honda 50 wasn’t exactly cool, and Japan still had a reputation for cheap and cheerful manufacturing. And combine that perception with the apparent complication of Japanese bikes and the perception they’d fall apart sooner rather than later, while not knowing where to get parts or fix it, and riders trod with caution.

After all, a Triumph’s car-like four-stroke engine, for instance, was a known quantity: it had been thumping around since 1937. And was perfectly good as it was, thank-you.

WEEEEEEEEyeewwwww….. bap-b-bap-bap-ber-bap-bap-tinkle-bap…..

What. Was. That..?

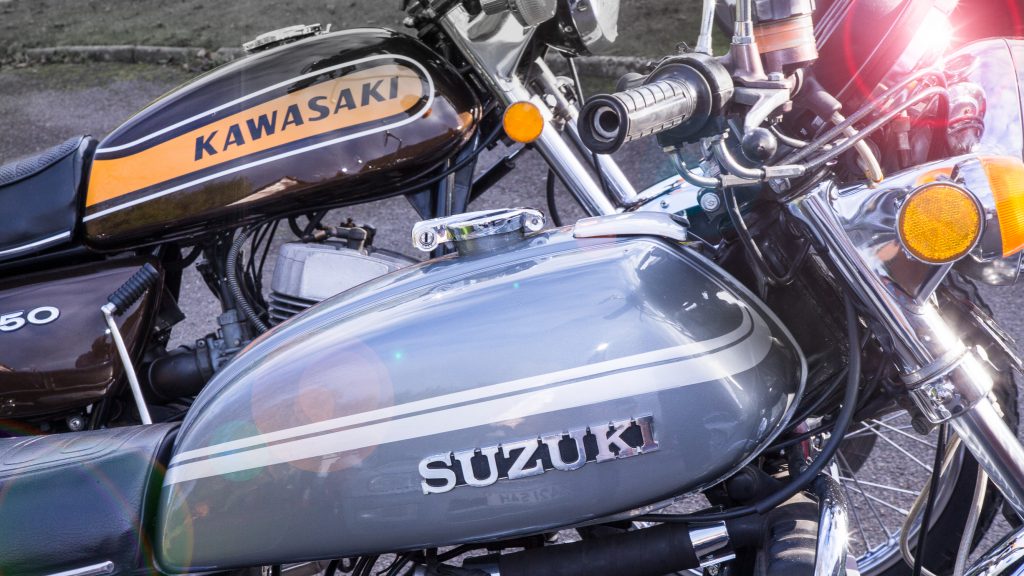

That was the future. Picture a 1972 Kawasaki 750 H2 being ridden at full beans then on the brakes into a corner. With a two-stroke engine it had just become pretty much the fastest way to get from zero to the national speed limit, and then keep going to 126mph. Its engine power – 74bhp – was just one horsepower less than was pushing along your cool uncle’s Ford Capri 1600L.

Granted, seeing a three-cylinder two-stroke 750 H2 on the road in 1972 meant you’d probably witnessed an early demonstrator or a journalist on a press bike, but that journalist was experiencing the future – and it would be a rave review, in straight lines at least.

From a standing start, the H2 would cover a quarter mile in 12 seconds. A Norton 750 would be along a second-and-a-half later on its way to a ‘mere’ 110mph top speed. The Capri? Add another eight seconds. And it couldn’t even pass 100mph.

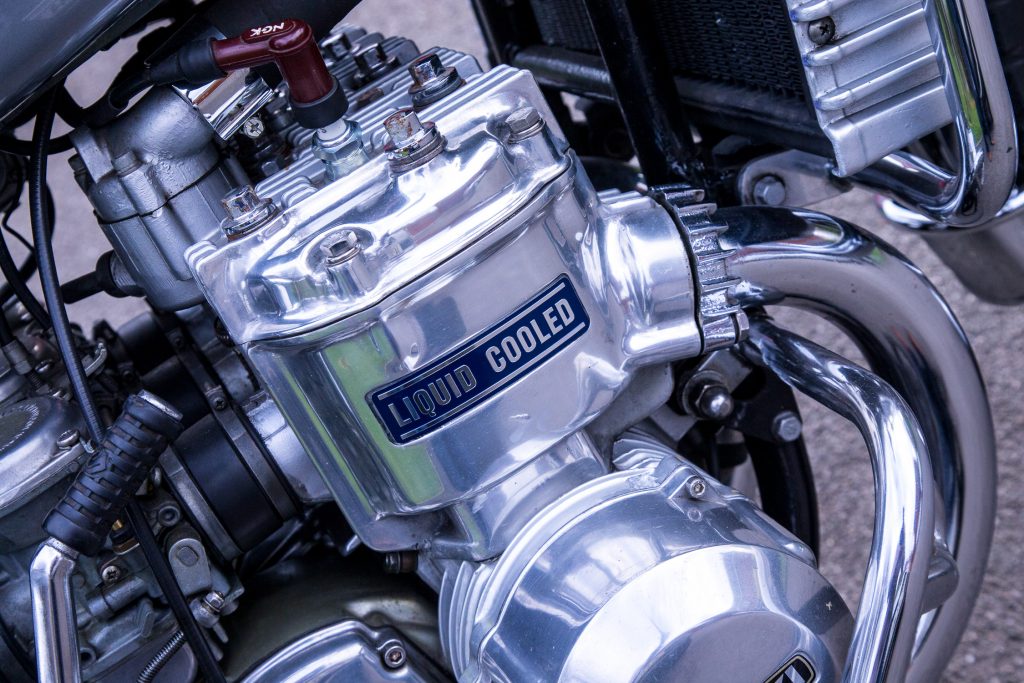

The thing about the H2, like the vast majority of bikes in the early 1970s, was that it was air cooled. Launched the same year as the H2, the Suzuki GT750 also had a three-cylinder two-stroke motor, but it was water-cooled. That was very unusual for a bike, although nothing out of the ordinary for a car, of course. And with 67bhp, and weighing in at 507lbs (230kg) – 40lbs more that the H2 – it was a stocky machine in its day.

While the H2 was something of a hooligan, the GT750 was a true Grand Tourer. Its engine sounded different, humming rather than howling, and the bike moved with far less drama and far more sophistication, and everything about it said you were about to go on a more considered journey as opposed to the bursts of adrenalin-pumping terror delivered by the H2.

GT750 riders were held in almost as much reverence as owners of expensive BMW motorcycles. Ben Walker, auctioneer at Bonhams, takes up the story. “The Suzuki GT750 was nicknamed ‘The Kettle’ because of its engine,” says Walker. “It was water-cooled: you checked the level in a radiator just like you did with your car. At the time it was one of very few liquid-cooled motorcycles, ever.

“It immediately put British bikes of the day back into the Iron Age.

“Around the same time, rival manufacturer Kawasaki introduced the 750 H2 Mach IV. It was as fast as it sounds. Even experienced motorcyclists thought it was completely mad. It didn’t have water-cooling; its engine was covered in fins and it relied on passing air to keep heat in check. As the air was usually passing very fast on an H2, that wasn’t much of an issue.

“If the GT750 was a private jet, the H2 was a supersonic fighter plane. They changed the expectations of motorcyclists forever, and 50 years later good GT750s retain enormous value – often £15,000-plus against less than £800 when new.”

They had in common different interpretations of a three-cylinder two-stroke engine. In the early ’70s, Japanese two-stroke motorcycle engines were significantly more powerful than British equivalents. Meanwhile, the only British two-stroke was the 125cc or 175cc Bantam, based on a pre-WWII German design.

For the uninitiated, in a two-stroke engine, the entire combustion cycle is completed in a single piston stroke: a compression stroke followed by the explosion of the compressed fuel. During the return stroke, the exhaust is let out and a fresh fuel mixture enters the cylinder. The spark plugs fire once every single revolution, and power is produced once every two strokes of the piston. The design requires the oil to be pre-mixed in with the fuel, and the specially-configured exhaust results in a unique resonance. For these reasons, two-strokes sound like nothing else, with a high frequency sound, and smell like nothing else, thanks to the burned-off oil.

David Hewitson, 57, chairman of The Kettle Club has two GT750s – a 1975 “A” model and a 1973 “K” model. The club’s membership has doubled in the past five years to more than 820. He estimates there are two thousand GT750s left, with many members having more than one – and one member has seven. He and fellow members often go on ride-outs, sometimes riding for a thousand miles or more.

But he advises being mindful that while an early model will eke out up to 55mpg, later models, which were in a slightly higher state of tune, will slurp at around 38-40mpg.

As you’d imagine, Hewitson is in no doubt that they’re “great bikes” but he says while the H2 engine’s power delivery is something that can take some getting used to, the GT750 was immensely driveable by comparison. “There’s no powerband at all, it’s like riding a four-stroke,” he reports, which frankly may serve to egg on enthusiasts further.

When it comes to drawing a comparison between these two pin-up bikes of the ’70s, who better to ask than Andy Stait, and engineer from Worcestershire. Stait has both a 1976 GT750A and a 1975 Kawasaki H2 750B, and he’s in no doubt as to the differences in character: “The H2 is an animal. The GT750 is a refined gentleman of a machine.

“The Kettle you can take it up through the gears with a really nice power curve, but on the H2 you hit 6000 revs and everything goes mad for the next 2000rpm.

“Some owners ride them all the time only in the power band. It’s for the excitement. I’m sure Kawasaki designed it that way.

“H2s have a bad reputation when it comes to handling, but undeservedly. The H2 is nowhere near as hair-raising as the 500 H1. I’d even say the H2 handles better than the Kettle.”

Nigel Hughes, of Classic Bikes Northwest, near Wigan, restores and sells “modern classic” Japanese bikes, and he has fond memories of the Suzuki in period.

“Back in the day I bought a Triumph and my friend bought a GT750. We were forever swapping: we loved each other’s bikes. The sound, the smell, the acceleration – the GT750 was a spaceship compared to the Triumph.

“I have a ‘Kettle’ at £8500. £12,000-£15,000 is not unremarkable for perfect machines, but I’d be wary of riding one worth so much – and classic bikes really should be ridden.”

Frank Hayes of Steel City Classics in Sheffield won’t forget his introduction to the H2: “People liked them because they were so quick. But they were unpredictable. I test rode one, and the dealer said to be careful. At first I thought it was quite a pleasant bike – until I held the throttle wide open. It nearly pulled my arms out of their sockets. Despite that, they’re incredibly desirable. There’s not many about; definitely one to invest in.”

Those that missed out the first time round, or riders who want to rekindle a relationship with either bike, are likely to be wondering which would be the better buy. That ultimately comes down to the riding experience you want from the bike, as both machines are in demand amongst that ’70s teenage crowd that want to recapture a little bit of their youth. And who can blame them, when teenage dreams are so hard to beat.

Read more

Ride on time: 13 collectable motorcycles to buy now

Friends reunited: Why I need a Norton Commando back in my life

Like grandfather, like father, like son: the third-generation exhaust fabricator saving Britain’s classic motorcycles

I have a 1975 kaw 750 and a 1976 kh 500 love um take me back 40 years

Back in the day, I at the time was a 16 year old “Moped Monkey” but with the potential to become, “A proper biker”.

On Saturday morning outside our local chipshop, the lads would meet up to discuss bikes and, “stuff”.

The two legends on the circuit at the time were Aden and Alan.

Aden rode a Suzuki GT 750, With from what I remember, a three into one expansion chamber, ace bars and rearsets. His mate Alan rode a Blue H2 750.

The two were young and more than a bit crazy. You would hear them first, then see them do a, “fly by” at vastmeggaknots followed by a blue haze and that unmistakable smell of two stroke.

This particular Saturday, both of them parked up. I was giving Alans H2 an admiring look. He then said those very unlikely words to me. “Do you want to have a go on it”?

I thought carefully for a moment, thinking, “If I say yes, he is then going to tell me to get lost or far worse”. In a fraction of a second I decided to say, “Go on then”

He handed me the key and said, “Once round the block, and that’s it, You bend it, you mend it”!

My mouth had gone dry with tension and excitement. All eyes were on me. I kicked the beast up, and Alan had to give me a friendly push to get her off the centre stand. “Take it steady or she will chuck you off”. I was on my way! Jubilation,Fear, Exhilaration, Excitement, All emotions rolled into one. I didn’t however guild the lilly, and got it back to a very anxious looking Alan. I was shaking with adrenal rush.

I consider this was the day that I earned my spurs!

Here I am now in my sixties, and have just managed to buy my very own, UK registered fully restored H2 750.

I know where Alan lives, and fully intend to visit him, ask him if he wants a go, saying those immortal words, “If you bend it, you mend it”!

A moment in time that I will never forget.

This has to happen, Martin!

I was sixteen when I purchased my first street bike… a 1976 KH500 triple (H1) that almost killed me when the middle cylinder seized. I wish I had known the Suzuki GT750 was such a great bike… I would have been much better off with a water cooled two stroke because I liked to go touring too. The Kawi H1 wobbled above 90 mph so I put a steering stabilizer on and then it went above 100 mph without wobbling on a long straight highway… then the middle cylinder suddenly seized at about 110mph and the rear wheel locked up… I slid, went down in the grass and the bike was totaled. Fortunately, I didnt hit anything and walked away. After that, I got myself a water cooled Honda CX500

I bought my Kettle for £610 in November 1975 and still have it (an L). I could not afford a new one as they were just over £800 at the time. I was very happy that I managed to get £40 off, as the seller wanted £650. I’ve spent many thousands on it since and it is pretty much exactly the same as it left the factory (except for some Barry Sheene inspired lower flatter handlebars). Next April it will be 50 years old and it still brings a smile to my face every time I ride it. I’ve had many newer more modern bikes but my Kettle is still the one that has the most character.

We knew a guy that made fuel injection (machinist by trade) for an H2 back in the 80’s. It would flex the wheelie bar and jump in the air like a grasshopper. I own a Hayabusa and it doesn’t scare me like that bike did.