Four decades on from its launch, Harley-Davidson’s original FXST Softail is not a bike that would stand out in most crowds. It’s a simply styled cruiser with raised handlebars, a thick dual-seat, and an air-cooled V-twin engine with cylinders set at the Milwaukee marque’s traditional 45-degree angle.

But that first Softail more than justified the swirling dry-ice drama of Harley’s publicity photo. In fact, this relatively restrained 1338cc model is among the most significant in the company’s 121-year history.

Back in 1984, the Softail was one of the five models fitted with Harley’s Evolution V-twin engine. With its aluminium cylinder barrels and heads, and more importantly its increased performance, cooler running, and much improved reliability over the previous Shovelhead unit, the Evolution brought the ailing firm rumbling out of the dark ages and into the light.

The FXST offered an additional attraction with its chassis. Its Softail name highlighted the new steel frame whose hidden suspension units cleverly allowed a comfortable ride while giving the impression of an old-style “hardtail” rear end. Before long there would be a whole family of Softails.

Most importantly of all, the Evo-engined models appeared at a pivotal time, like a cavalry division charging over the horizon just as the surrounded troopers with their antiquated rifles were facing slaughter.

Harley-Davidson’s situation in 1984 was dire. The firm has had well-documented worries in recent years, what with its ageing customer base and production falling below 200,000 from a 2006 peak of almost 350,000. To put that into context, however, while Harley engineers had been finalising development of the Evolution engine in 1982, production had been less than 25,000. This was below the level agreed with its financial backers, who were entitled to foreclose at any time. The loss-making company had recently laid off 40 per cent of its workforce and cut the salaries of those who remained.

The US motorcycle market had plunged in the late 1970s, unheeded by both Harley and the Japanese manufacturers, who had continued to increase production until they had warehouses full of bikes that could not be shifted even at a discount. Worse still for Harley, its owners AMF (American Machine and Foundry) had boosted production by compromising on quality. By 1984, the result was unreliable bikes, dissatisfied customers, and unhappy dealers faced with increasing warranty work. The firm’s reputation was arguably at an all time low.

At least there were some positives. Back in 1976, Harley executives had drawn up a long-term plan based on two powertrains: an updated aircooled V-twin, which they called Evolution; and a liquid-cooled family of V-configuration engines, named Nova.

Development of both began the following year, with the Evo project in-house, and Nova contracted out to Porsche Design, because Milwaukee lacked the resources to do both simultaneously. When, in 1981, financial constraints meant that only one project could continue, the Evolution was chosen.

By this time, however, Harley-Davidson was a very different company. A management buyout earlier that year had seen a group of 13 senior executives, led by Vaughn Beals and including styling chief Willie G. Davidson, raise over $80 million to take control from AMF. “The Eagle Soars Alone,” ran the celebratory advertising, but the company remained in a desperate position.

The Evolution engine had been slated for introduction with the 1983 model year, but there was a distinct possibility that Harley’s banks would pull the plug first. That this didn’t happen was partly due to Beals’ successfully petitioning the International Trade Commission to put tariffs of 45 per cent on Japanese motorcycles of over 700cc.

President Ronald Reagan signed the tariffs into law in April 1983, but that was far from the end of Harley’s problems. Beals and engineering chief Jeff Bleustein regarded restoring the brand’s former reputation for reliability as so vital that the Evo motor’s introduction was delayed by a year to allow further development.

“I don’t think we ever made a tougher decision,” Beals later said. “The market was terrible, which meant we needed the engine sooner rather than later… But the one vow we took, because of the reputation we had, was that when the Evolution engine came out it would be durable, oil-tight, and bulletproof. We finally decided that the 1983 introduction was too risky, because we weren’t yet confident that it was bulletproof.”

The extra time was well spent. Harley’s engineers continued their more-than-5000 hours of dyno testing, redesigned some parts, and refined manufacturing processes. Development riders added to a reported total of 750,000 miles of endurance road work and high-speed laps of the test track at Talladega in Alabama.

The result justified that cautious approach. The Evo engine retained its Shovelhead predecessor’s 1340cc (80 cubic inches) capacity, its cylinder dimensions, crankshaft, and basic bottom-end layout. But almost everything else was new, including the aluminium head and barrels, smaller valves, narrower valve angle, camshaft profile, stronger conrods, flat instead of domed pistons, reshaped combustion chambers, and higher compression ratio.

Performance was significantly improved in every respect. Peak power output was up by ten per cent, to 71.5bhp at 5000rpm. Torque improved by 15 per cent and moved lower down the rev range. Fuel economy was improved, and weight was reduced by 9kg. A comprehensively redesigned lubrication system cured the Shovelhead’s habit of leaking as well as burning oil.

The new engine was nicknamed the Blockhead, extending the line that had begun with Flathead, Knucklehead, and Panhead, but it was more commonly called the Evolution. Either way, it came with a 12-month, unlimited-mileage warranty. It was an instant success.

Some US motorcycle magazines had previously been reluctant to test Shovelheads, due to their many issues, but response to the Evo models was much more positive. “By now you’ve heard all the rumours and read all the speculation. Stop the presses, it’s true,” reported Cycle World about the Electra Glide Classic, which it described as a “thoughtfully conceived, carefully executed major overhaul that manages to blend the tradition of the past with the ideas of the present, to come up with something that’s both modern yet familiar.”

After riding the Electra Glide in the States, British freelancer Alan Cathcart described the Evo engine in Bike as “a quantum leap forward from the days of the iron jug Shovelhead… a successful amalgamation of traditional values and modern technology, of simple pushrod design and refined execution.”

Cycle magazine was positive about another model, the half-faired FXRT Sport Glide, describing it as a “contemporary motorcycle, albeit a very expensive one, rather than a curious alien from another era… The Evolution indicates that Harley-Davidson is making progress, and at an increasing rate.”

Motorcyclist was similarly impressed by the Sport Glide. “For those who wanted to see if Harley could build a real, honest-to-Davidson 1984 motorcycle, feast your eyes. The ’84 season is here – and Harley is right here with it.”

If the models that gained Evolution engines instead of Shovelhead units all contributed to the fightback, it was the all-new FXST Softail that would make the biggest impact. Its hardtail-look rear end had originated with an independent engineer from Missouri named Bill Davis, whose modified Super Glide had caught the eye of chairman Vaughn Beals at a Harley rally.

Beals negotiated to buy the rights, and Willie G. Davidson fashioned a relatively lean and simple cruiser whose rigid-look rear end incorporated a hidden pair of shock units sitting horizontally beneath the engine. The Softail engine was held solidly rather than rubber-mounted as with the other Evo units, and for its first year only it had a four- instead of five-speed gearbox.

The Softail wasn’t the most comfortable or practical of Harley’s 1984 models, and it wasn’t the least expensive, either. But its blend of more up-to-date engineering and determinedly old-fashioned style hit the spot, and it quickly became not only very popular but – even more importantly – very profitable too.

Not that Harley-Davidson was out of financial trouble just yet – far from it, in fact – even though the year ended with US sales up by 31 per cent to over 38,000, in a market that continued to fall. Domestic sales were up again in 1985, putting Harley second behind only Honda in the 850cc-plus category, but that was the year in which the company came closer than ever, before or since, to going bust.

The problem was that Harley’s backer, Citycorp, which had previously backed the company through the difficult times, had new people in important positions. They decided that another recession was looming – and that Harley, despite the upturn in its fortunes, would not survive it, so Citycorp’s best option was to liquidate the firm.

In March 1985, Harley was given an extended deadline of 31 December to find a new backer or file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. Beals later spoke of “hawking begging bowls round Wall Street” that summer as he and chief financial officer Richard Teerlink struggled to convince potential investors that Citycorp’s pessimism was unjustified.

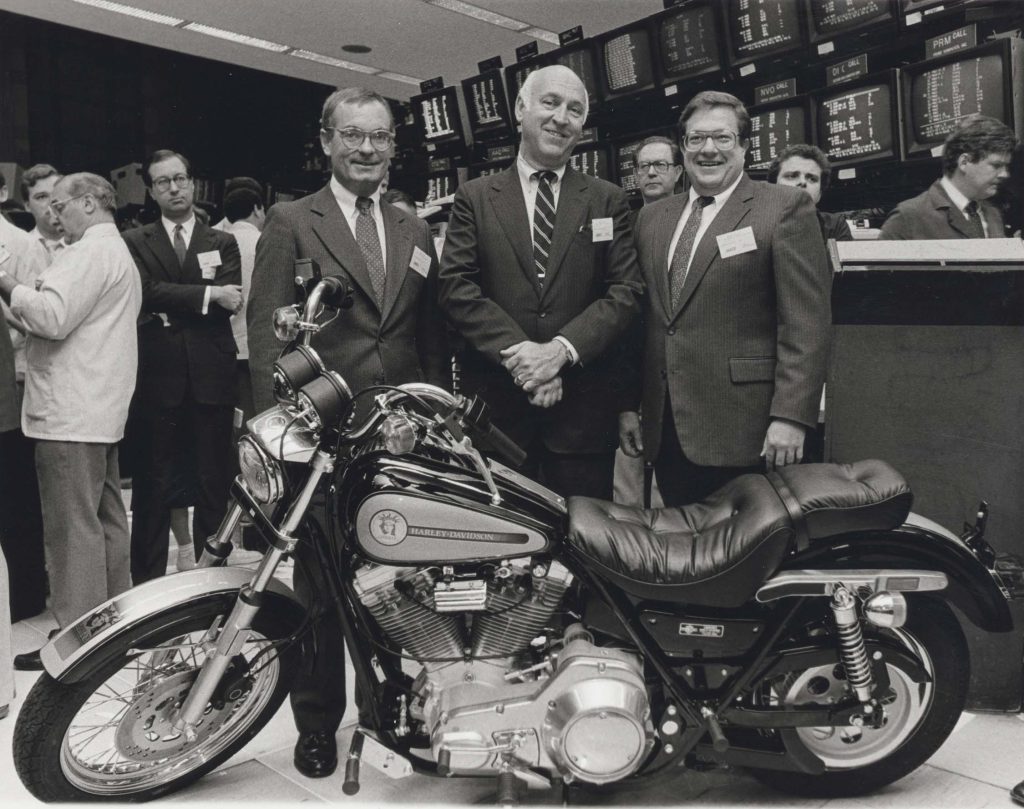

Finally, with time fast running out and all alternatives exhausted, Beals, Teerlink, and colleague Tom Gelb were introduced to a Harley-riding banker named Bob Koe, of Chicago-based Heller Financial, who set up a meeting with his boss, Norm Blake, on the morning of 23 December. Blake listened to their pitch… and turned them down.

Somehow, with the bankruptcy seeming almost inevitable, the Harley trio persuaded Koe to arrange another meeting with Blake that afternoon. They finally agreed a deal, more generous to Heller, which gave Citycorp $49M, and Harley $49.5M of working capital. Even then, holiday season delays meant the final transaction was completed with minutes to spare on 31 December.

Harley was saved, and Heller’s confidence would be rewarded as the Milwaukee firm defied the general downturn to begin an astonishing period of growth. In 1986, it matched Honda for big-bike sales. The following year Harley was listed on the New York Stock Exchange, and also petitioned the IRC to end the tariff on Japanese bikes ahead of time. President Reagan visited the factory in York, Pennsylvania, to offer congratulations.

A succession of Evolution-engined models powered the recovery. The FLST Heritage Softail of 1986 featured a fat front end inspired by the Hydra-Glide of the 1950s. The Low Rider Custom had a skinny 21-inch front wheel, high bars, and lots of laid-back attitude. In 1988, the FXSTS Springer Softail went further back through time with its updated version of an old-style springer front suspension system.

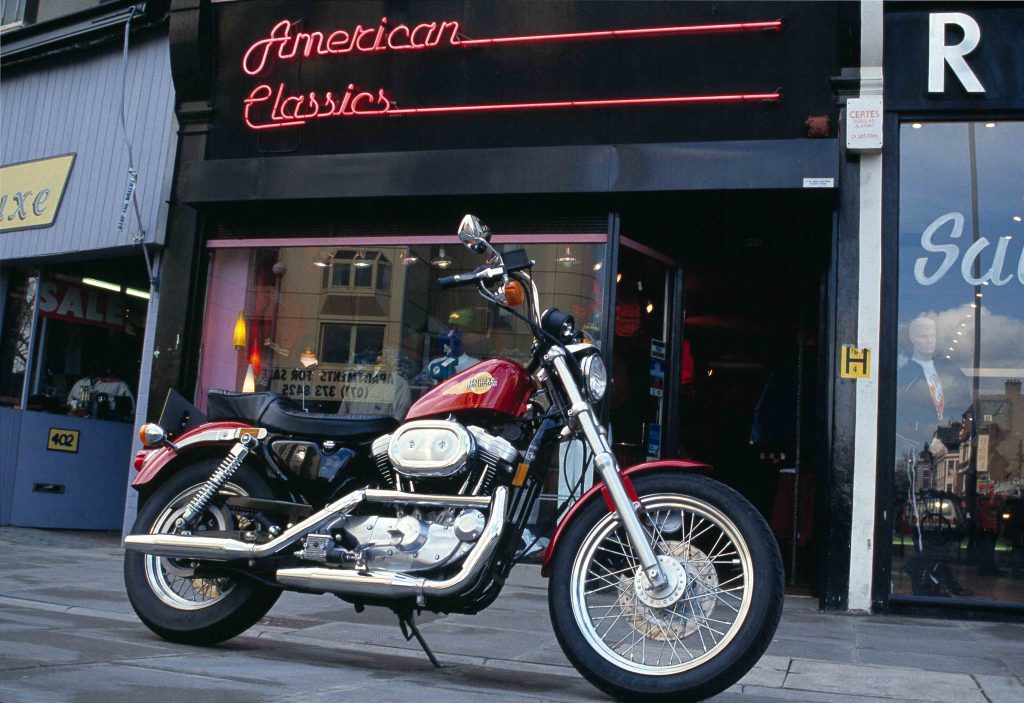

The Sportster family was also updated with Evolution engines, starting in 1986 with an entry-level model in traditional 883cc capacity, followed soon after by a similarly styled 1100cc variant. Both were popular, the smaller model boosted by Harley’s innovative offer to repay the full $3995 price if its rider traded up to a big twin within two years.

In 1990 came the unmistakable FLSTF Fat Boy, with its disc wheels, industrial look, and silver finish with yellow detailing. A year later it was followed by the Dyna Glide Sturgis, which was named after the South Dakota rally that had become an August fixture for a growing legion of Harley riders.

Willie G’s final Evolution-powered project was one of his finest: The FLTR Road Glide of 1998 featured a frame-mounted fairing and a long, low look that would remain popular for more than two decades. A year later, the Glide and most other Big Twins were fitted with the new Twin Cam 88 engine, a bigger, more powerful V-twin that was another step forward.

The Evo unit continued to power some Softail models for a couple more years, along with the hotted-up, limited-edition FXR Super Glide variants that began the Custom Vehicle Operations line in 1999 and 2000. By this time, Harley’s total production was nudging 200,000. Revenue was close to $3 billion, and profit almost $350 million, the company having set new records for 15 consecutive years.

The Evolution engine, it’s fair to say, had proved a considerable success.

How about the 89 sporty when did that come in the manufacturing kind of silly question ❓

Hello iron horse riders ,my 2009Harley Softail is far the best I ever owned,but my shovel did kick ass at times when I raced,and beat a firebird,mustang,Camero,and a police officer only to be stopped by a road block,do the crime pay the judge,this Softail turns heads all the time and wakes up the neighborhood as well,keep up the good prestigious work,the bigger the better the faster.

Why don’t you ever put out a article on the Dyna wide glide which was a very exceptional motorcycle with its back to age look it was a good chopper I don’t know why you stopped making it

Hello I have a 2000 Harley soft tail duece fxstd still in mint condition origami miles 4.765 as of 5/4/2024 love that bike and it’s color is purple major head tuner lots of coments.

Important details seldom mentioned. Asking for the tariff to be removed early and the year delay to get it right !

Our family owns 2 Evolution bikes. A 1984 FXRD and a 1994 Heritage softail. We love to ride them both.