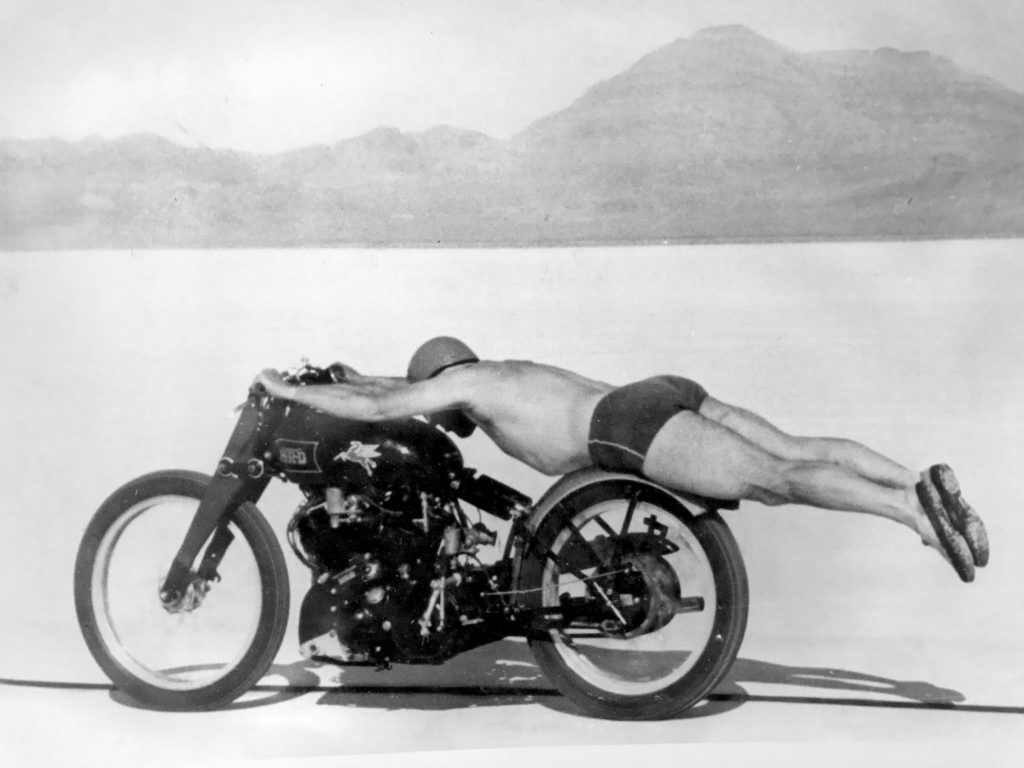

Imagine if you can, taking off all your clothes save a skimpy pair of budgie smugglers, a swimming cap, and a pair of pumps, then lying prone on a factory-tuned, super-powerful British motorcycle and galumphing across the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah at a new land speed record of 150.313mph (241.905 km/h). Can you feel the sting of those insects hitting your bonce yet?

This was exactly what Roland ‘Rollie’ Free did on 13 September 1948, creating in the process not just a new speed record but also one of the most famous motorcycle photographs in history. He’d already just made a 148mph record run in full leathers, but he wanted to top 150, and the leathers and begun to come apart at the seams, so what else was he to do?

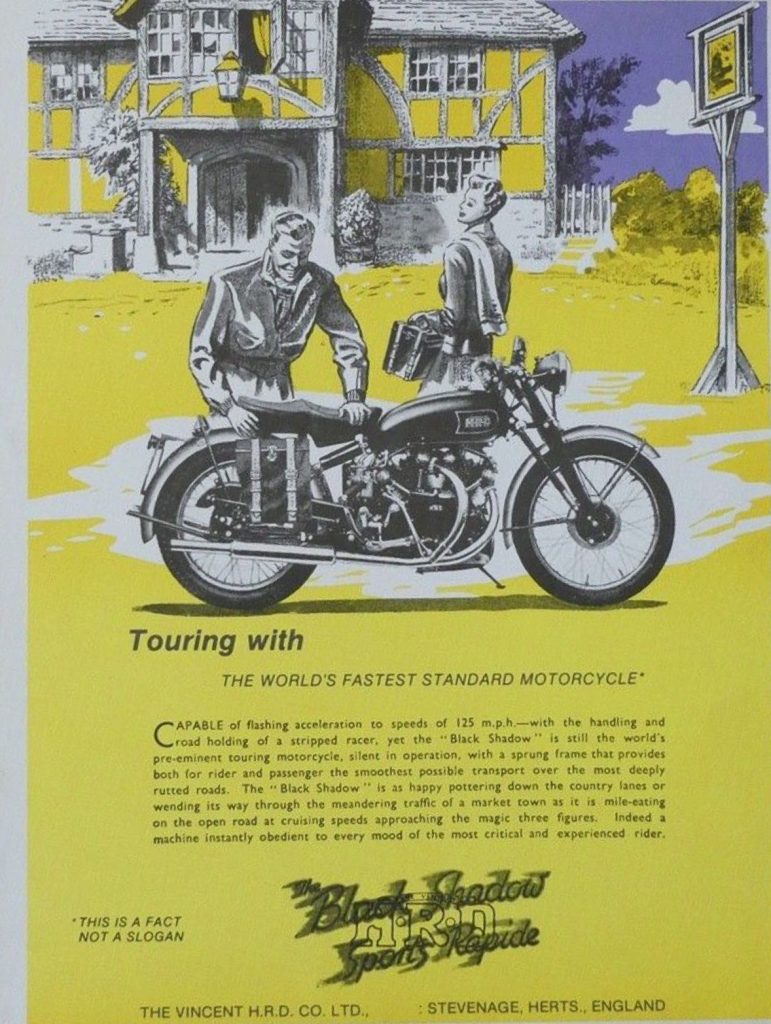

The bike? The Vincent HRD Rapide, Stevenage’s finest, and though opinions differ on whether Rollie’s was a Black Lightning or Black Shadow, either would qualify as one of the most famous of machines – perhaps even the first-ever superbike, especially the latter – which was advertised as “The world’s fastest standard motorcycle: THIS IS A FACT – NOT A SLOGAN!”

It was designed by the two Phils, Vincent and Irving. The first was an Anglo-Argentine old Harrovian, whose purchase of the HRD factory in 1928 for £30,000 had been funded by his father. The second was a gifted Australian engineer, journalist, author and, ultimately, a holder of the MBE, who came over to the old country in 1930. After seeing service with Vincent, Irving was commissioned to design Jack Brabham’s Formula 1 Championship–winning Repco Brabham engine.

The Black Shadow was introduced in 1948 as a faster version of the road-going Rapide. And what a year that was. Just three years after the ending of World War Two, 1948 saw the formation of British Railways; London hosting the Olympics; Gentleman’s Agreement with Gregory Peck and Dorothy McGuire winning the best picture Academy Award; the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi; the formation of NASCAR by Bill France Sr; the first broadcasts from the ABC; the introduction of the first Land Rover model; the docking of HMT Empire Windrush; US president Harry Truman introducing a peacetime draft and the end of racial segregation in the workforce and military; Goodwood Circuit hosting its inaugural motor race; and Cadillac introducing the first-ever tailfins on a motor car. Phew, it must have been a relief to get to Christmas.

Powered by a 998cc, four-stroke air/oil-cooled V-twin engine of enormous physical size, with the V running longitudinally in the much stripped-down frame, this £400 machine was sought by wealthy enthusiasts even from new. There was also a race version, the Lightning, which cost £500.

You need to step carefully in Vincent land. As Kevin Cameron writes in his book Classic Motorcycle Race Engines, “Vincent fanciers wax lyrical in their partisanship. Any outsider utterance not adhering to their sacred texts risks indignant comment…”

Well let’s go with one, then, made by Hunter S. Thompson in his book Fear And Loathing In Las Vegas: “If you rode the Black Shadow at top speed for any length of time, you would almost certainly die. That is why there are not many life members of the Vincent Black Shadow Society.”

Thompson had ridden a Black Shadow in the early 1970s and was highly respectful of its speed and reputation, suggesting it “could outpace an F-111 [jet fighter] until take off,” though there is no evidence he ever actually put this to the test.

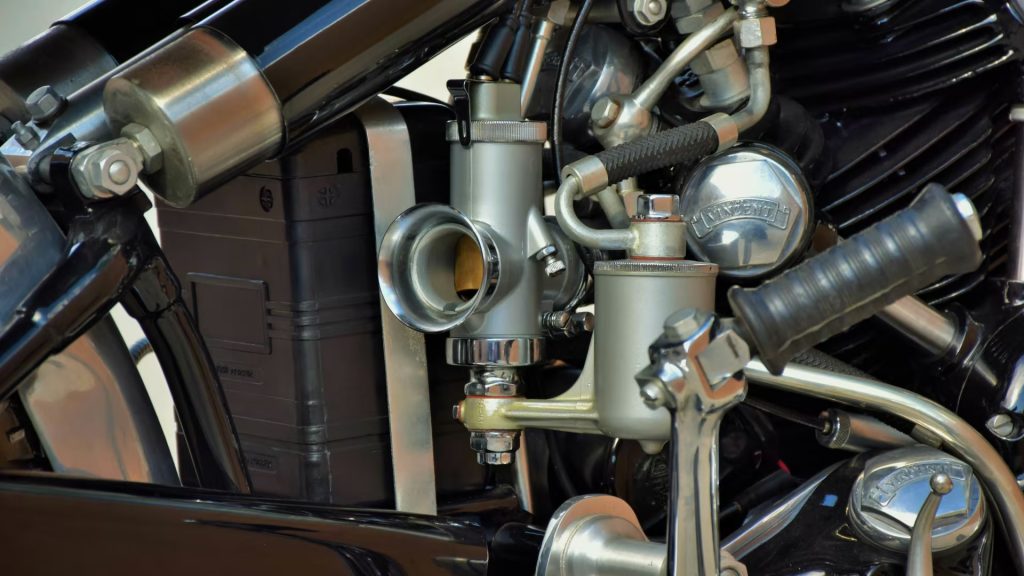

Even if you hadn’t ridden an example, the sheer size and brutal details of the dry-sump V engine in a Vincent Black Shadow would be an intimidating sight. Do the world’s stocks of metal polish allow more than two Vincents to be on the road at once?

The huge dished timing cover almost obscures the massive cylinders on the right-hand side, while the short fat pushrod tubes (for more accurate valve control), serpentine oil feeds, concentrically curved exhaust headers and Amal carburettors on stubby intake manifolds were convincing demonstrations of the short-sighted Irvine’s ability to visualise engineering design. It’s rumoured he simply did the same for the eye-sight charts prior to his entry medical into the Field Artillery for his Australian National Service.

“Phil Irving was a multi-talented engineer whose ‘minds-eye’ saw clearly,” writes Cameron. And nowhere does this prove more true than in the Black Shadow’s lower frame-less construction, which not only saved weight, but also the use of steel, which in those post WWII times, was in very short supply. The machine had been developed by the factory by a team consisting of Irving, Vincent’s test rider and racer George Brown, and his brother Cliff.

The prototype was an early Rapide model, which had been withheld from sale for being too noisy (rumoured to be so because it had been filled with kerosene rather than engine lubricating oil) and had been tuned by the trio.

This much worked-about machine was subsequently was nicknamed ‘Gunga Din’. This was after Motor Cycling magazine tester and racer Charles Markham wrote an evocative road test in which he quoted Rudyard Kipling’s eponymous poem.

“Though I’ve belted you and flayed you,

By the livin’ Gawd that made you,

You’re a better man than I am, Gunga Din!”

The Black Shadow’s engine was effectively a much tuned-up unit from the Rapide, with a smart black paint job and a baked-on black finish. With aluminium pistons, forged connecting rods and those twin Amals, it produced about 55bhp, which gave the Black Shadow a top speed of 125mph. This was superlative performance for the day.

It was strong, too, and eminently tuneable, which gave racers and tuners a chance to add to the legend. As well as George Brown, who carried on the Vincent story on the drag strip with his specials Nero and Super Nero, other racers came calling, with John Surtees successfully racing single and V-twin Vincents. And in the 1960s, Swiss tuner Fritz Egli updated the Vincent with a special frame and Italian racing components. Vincent V engines also found themselves in successful side car outfits, including ‘The Fast Lady’.

Then there were the specials, none more so that the Norvin, the marriage of a stonking Vincent engine and the Rex McCandless–designed Norton featherbed frame considered one of the most advanced of its time.

“The Vincent engine was the most powerful available at the time, and Norton did make the best frames,” says Michael Digby, an engineer who volunteers at the Brooklands Museum and is currently restoring a couple of Vincents. “But it was a very tight squeeze to get a Vincent engine in there, and lots of specials had stretched frames as a result.”

There’s no Norvin more famous than the mighty ‘Armageddon’ ridden by Paul Sample’s cartoon hero Ogri, a steadfast bike which could see off many a Japanese modern machine. Tested by Oli Duke for Bike magazine in 2016, the experienced writer liked the lazy power and 120mph top speed, but found it rather wanting for brakes.

It’s been a while since I rode one, but I remember a warmed-up machine starting easily despite Richard Hammond’s issues starting on a Black Shadow in Top Gear’s ‘Race to the North’ episode in 2009. Frankly, you need a bit of heft to get the 84mm pistons dancing. There are modern electric starts available, but they’re a bit weedy. Even with a very modest 7.3:1 compression ratio, the sheer size of the engine means you’re well advised to retain a kick start. My friend’s Black Shadow has an aftermarket electric start, which gives two attempts to start before it fizzles into a sulk.

Dakka dakka, dak, go the exhausts before a clunk as you select first gear in the four-speed ‘box. The servo-assisted clutch might be light, but it’s a binary device that doesn’t tolerate much slip; once in gear, you are moving, whatever alternatives you might have planned. Gearing is long, and despite its modest power output, the bike feels almost unstoppably powerful, especially as you move into second, where it will do 91mph, and then third, where it’ll do 110mph. Other performance data sees 0–60mph despatched in around 6 seconds, and for those who need it, a return of about 50mpg. So with a 3.5-gallon fuel tank (one of many different sizes), you’ll easily get 150 miles between fill-ups.

No rev counter of course, just a 150mph speedometer sticking up into the breeze like the station clock. Once into fourth, you seldom need to change again. A twist of the wrist is all it takes to have you heavily into licence threatening speeds. Remember, though, the brakes are hopeless and at night, the headlamp performance was once described to me as ‘following the puddle.”

While the cantilever rear and girder-fork front suspension would send warning signs to those who would notice, in fact a Vincent steers naturally on a decent road even if the ride is best described as bum numbing. Its 56.5-inch wheelbase and 32-inch seat height give a feeling of sitting in the machine rather than on it, and with a 458lb dry weight, even with fuel and oil, it should be under 500lb. The result feels manageable and quite deliberate as you counter-steer the almost flat bars and tip the nose into a turn and then power out with that characteristic exhaust noise – and smoke!

So what is the appeal of these extraordinary machines?

“It’s the effortless power,” says Michael Digby, “though the 500cc machines can also be delightful.”

With three different series of Black Shadows produced until the demise of the firm in 1955, you need to know what you are buying. And it’s better to buy a whole one, as they say.

“You need to know what you are looking at,” Digby says. “While the end product was very good, the assembly of them is tricky; there are lots of parts that require shimming.”

He quotes Sammy Miller on the subject of Vincents: “If they come in a box, the first six inches on top will be shims.” Once they are set up, though, says Digby, “they’re very good and simple.

It’s that difficulty in setting them up which probably explains why so many Vincent Black Shadows ended up dismantled in crates in the first place. Again, Digby has a warning: “You have to make sure they are complete, as getting hold of missing pieces can be enormously expensive. Always make sure it’s all there before you buy.”

With prices upwards of £50,000 and into the £90,000s with an interesting provenance, it’s tempting to go for a cheaper, crated, dismantled machine, but the parts and the work will seldom pay back. While the attrition rate will have taken a fair few, factory records show that 1774 Black Shadows were made, plus an additional 15 White Shadows with the engine polished up rather than being black-enameled. In other words, they’re available.

I think they are very lovely things, understated as a British super bike should be, and distinctively and beautifully engineered. And in recent years, there’s been a bit of an easing of the prices, though again Digby has a wry warning, particularly for those hopeless optimists who are smaller in stature than Richard ‘Hamster’ Hammond.

“Prices are starting to drop a bit,” he says, “as the people who can afford them can’t kick them into life anymore…”