It’s ten years since Indian was reborn under the ownership of automotive giant Polaris. Since then the famous US motorcycle marque has grown its range to more than 20 models, increased annual production to over 30,000 bikes, and outclassed its old rival Harley-Davidson to win a sixth consecutive championship in SuperTwins, the top division of American Flat Track racing.

But the Indian story of the previous few decades was very different – a lot less smooth and far more dramatic. Until the brand was bought by Polaris in 2011, Indian had been making headlines for years. Not with new models or race victories, but with a succession of scandals, courtroom cases, and failed attempts at revival.

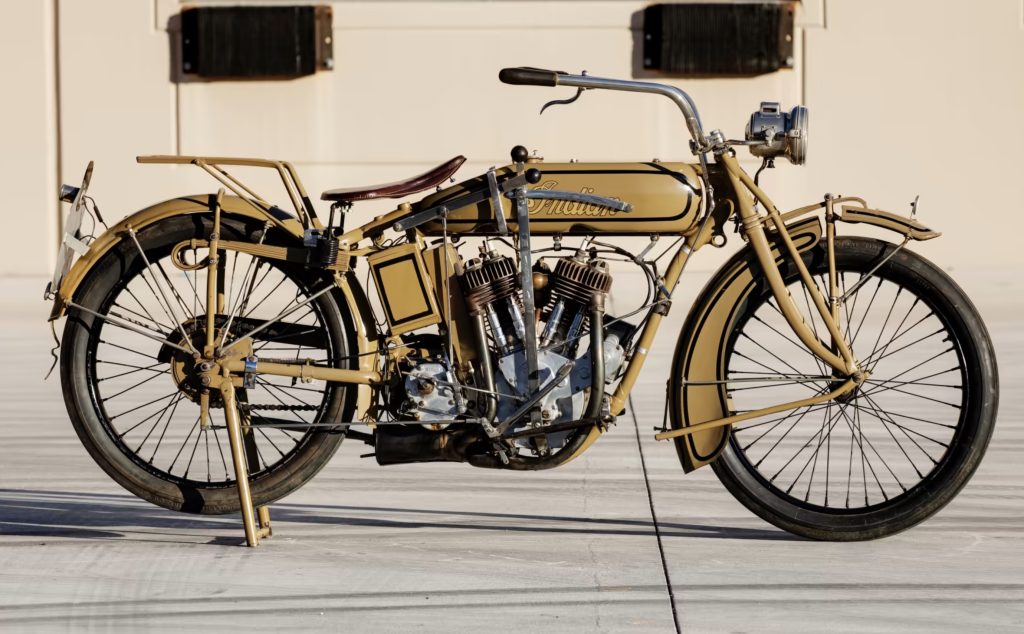

The fuss was easy to understand, because Indian is one of the great names of American motorcycling, and it had fallen on very hard times. Founded in 1901, two years before Harley, the original firm from Springfield, Massachusetts, became the biggest US manufacturer by the early 1920s, promoted by the exploits of early board-racing stars and record-breaking long-distance riders including Jake DeRosier and Erwin “Cannon Ball” Baker.

Models including the Powerplus, Scout, and Chief kept Indian healthy into the 1940s. The firm also built an inline four, after taking over Ace in 1927. But a move to parallel twins proved disastrous, sales and profitability fell, and the Springfield factory ceased production in 1953. For the next few decades the Indian name was used to sell small bikes made in Britain and elsewhere, until its use faded in the 1980s.

Interest in Indian reawakened in the early 1990s when, with Harley sales growing so fast that the factory couldn’t keep up, it became clear that there was room in the booming US market for its former rival. Here is where the story gets messy. Two men independently claimed the Indian name, each with the stated intention of producing high-quality V-twin motorcycles. Unfortunately, they not only failed to build any bikes, but showed no sign of intending to do so.

First came Philip S. Zanghi II, a Californian businessman who in 1990 claimed to have bought rights to the Indian name, for the sum of one dollar, from the last person to use it for selling mopeds in the 1970s. Zanghi announced plans for a new Indian Chief, to be built in small numbers and sold at a high price. He began selling Indian merchandise, ranging from leather jackets to jewellery, and toured the world selling Indian import rights for tens of thousands of dollars apiece.

Zanghi’s motives became more clear when I visited Bob Stark, a revered Indian restorer, parts specialist, and former dealer who had been involved with the marque for half a century. Over several trips to Starklite Cycle’s base in Perris, California, Zanghi had agreed he would pay Stark to build a run of 100 Chief models. “He’d pay me the same shop rate I’d charge anyone who walked in the door,” Stark said. A contract confirmed the agreement, but the cash never arrived. “Everything was fine until it came to time for him to put out one dime’s worth of money. Then, nothing.”

Two months later, Zanghi sent Stark a licensing agreement whose contents were dramatically different to those of the original contract. By signing it, Stark would have agreed that Zanghi owned the right to produce Indians, he would have accepted Zanghi as an authority on their construction, and he would have handed his estimated $500,000 worth of Indian parts and tools to Zanghi, all while agreeing to put up the money to build the 100 bikes himself.

“I’ve probably got 25 per cent of the factory drawings. He has none and knows nothing,” Stark told me. “I don’t know what kind of idiot he thought I was, but with this he would have taken over my complete business within three months. I called him and said, ‘Philip, this sure as hell is not what we discussed.’ He offered to pay my way out to discuss it. I told him to forget it. But he got what he wanted out of me – he used my name. I’d had banks calling me. He used our background to try to get money.”

The other self-professed Indian saviour was Wayne Baughman, a former car salesman from Albuquerque, New Mexico. He also claimed rights to the name and announced plans for a new Scout model, powered by a 1410cc V-twin engine. When I visited him in January 1993, he insisted the Scout would be in production within six months. As his only prototype comprised an old Indian engine fixed to an aftermarket Harley frame by plastic zip-ties, this seemed very optimistic. (He did, however, have a nice line in Indian T-shirts and jewellery.)

Needless to say, neither of these characters built any bikes. Zanghi ended up in prison for a variety of offences including fraud, and Baughman extracted several million dollars from investors and enthusiasts, without producing anything in return.

The next false start involved genuine Native Americans. In 1995, it was announced the Indian name had been bought from the receiver by a firm called Eller Industries, which had agreed a deal with the Cow Creek band of the Umpqua people, to build bikes on their land in Oregon. Roush Industries, famed for building NASCAR racers, were hired to develop its V-twin engine. In 1998, the firm unveiled sketches of prototypes created by a designer named James Parker, who had recently shaped the radical chassis of Yamaha’s GTS1000.

All looked promising, until suddenly the deal was off amid rumours of financial problems. Instead, later that year a court in Denver, Colorado, awarded Indian rights to a group that had taken over the California Motorcycle Company (CMC). The firm from Gilroy in central California was one of the largest of the so-called “Harley-Davidson clone” manufacturers – firms that specialised in building bikes powered by engines built not by Harley but by S&S, whose big, aircooled V-twins closely resembled those from Milwaukee.

In 1999, the renamed Indian Motorcycle Company started production of a new Chief Limited Edition, a cruiser featuring a 1442cc V-twin engine – a Harley-based unit, like those CMC had used before – and Indian’s trademark huge fenders and curly script on the tank. When I rode the bike in Florida that year it seemed reasonably well built and finished, albeit with some rough edges, but was hardly an authentic Indian.

Four years later the firm launched a revamped Chief, powered by a new V-twin engine called the Powerplus 100, which had a larger 1638cc (100 cubic inches) capacity and still had cylinders set at 45 degrees, in Harley fashion, but did at least have some new features. The response of US cruiser buyers remained mixed. The firm had built 12,000 machines when, later that year, a backer pulled out and production abruptly ended.

This all-American tale then took a surprising diversion when in 2004 the Indian name was bought by Stellican, a London-based private equity firm run by Stephen Julius, a Brit with a classics degree from Oxford University and a business record that included successfully reviving “heritage brands,” including US boat firm Chris-Craft. Julius relocated to North Carolina, hired engineers to revamp the Chief, including an enlarged 1720cc engine, and in 2008 began small-scale production of some innovatively styled models.

The most eye-catching, if least politically correct, was the Bomber, a limited-edition Chief whose tank featured a cartoon Blonde Betty, who could be replaced by red-haired Ruby or dark-haired Debbie, according to taste. Other details included the distressed brown leather of its saddle and panniers, inspired by a WWII flying jacket, and the aero-style rivets on the trademark big front fender.

Julius positioned Indian as an “ultra-premium” brand, with prices above Harley-Davidson’s, and aimed to make a profit by selling just 500 hand-built bikes per year. He planned to export to Europe but faced problems in selling bikes in Britain due to another bizarre twist in the Indian tale, again involving a dispute over rights to the name.

Alan Forbes was a former musician and long-time Indian enthusiast who ran a bike shop called Motolux in Edinburgh, specialising in servicing, restoring and occasionally selling Scotland’s small band of old Chiefs and Scouts. At a Swedish rally in the late 1990s he met a group of locals who had built a giant, 1845cc inline-four cruiser that they called the Wiking (considering the name Viking too obvious), using a mixture of Volvo, BMW, and VW Beetle car engine parts and a chassis of their own design.

Forbes had long wanted to produce a bike and had seen the opportunity for a fresh take on the inline four that Indian had produced decades earlier. He had made a deal with the Swedes, and by 2000 they had developed a good looking if slightly agricultural prototype named the Indian Dakota – although it could only be called that in the UK, where Forbes had registered the Indian name. He announced grand plans to produce up to 100 Dakotas per year, but several years later was vague about whether any had been sold – or whether producing more than a small batch had ever been a realistic aim.

If the world’s finances had not gone into meltdown in 2007, perhaps the two Brits claiming the Indian name would have had to decide whether to share a pipe of peace or start swinging legal hatchets. Unfortunately for Stephen Julius, after three decades in which Harley-Davidson sales had boomed, he was attempting to relaunch Indian just as the global financial crisis sent sales of big, expensive American motorcycles plummeting. Even Harley struggled. Its new, much smaller rival didn’t stand a chance.

Yet Indian remained an ace among motorcycle brands. And in 2011, with the financial crisis finally over, a major player finally came to the table. Polaris already owned a motorcycle operation: Victory. It had launched Victory from scratch in 1998 and carefully built it into an established manufacturer that had sold more than 100,000 bikes. But fighting Harley’s century of tradition had been tough in such a nostalgia-led market, and Victory had struggled to achieved the sales that its models’ performance and quality merited.

Polaris had survived the recession in good shape, however, and was keen to expand. It even had funds for motorcycle development. It acquired Indian in 2011 – both the North Carolina and Edinburgh enterprises, plus any loose ends elsewhere – and invested further tens of millions of dollars in development, marketing, and machinery, including an assembly factory in Spirit Lake, Iowa.

In August 2013, the relaunched Indian unveiled a range of three all-new Chief models. In many ways they resembled previous attempts, but they were not just superior in performance and quality; these Indians also differed by being widely available, competitively priced, and extensively marketed. A second family of Scout models followed just a year later. By this time Indian was outselling sister brand Victory, which would be closed down in 2017.

For the last decade, then, Indian’s turbulent history has been shaped by an owner that could do it justice, and the firm is already competitive with Harley-Davidson on the racetrack, if still well behind in showroom sales. After all the fighting over the name, Indian still faces the issue of cultural appropriation that has led to the rebranding of many US sports teams. We will all have to wait and see how that plays out, but in the meantime, this most enduring of American marques rides on.