Parallel twins are currently motorcycling’s dominant force. Honda’s new Hornet and Transalp are earning rave reviews. Aprilia, BMW, Husqvarna, Kawasaki, KTM and Royal Enfield have popular families. Fantic’s first ever twin borrows its engine from Yamaha’s MT-07 and Ténéré, which sell by the boat-load. Even Suzuki’s latest V-Strom is a parallel not a Vee.

And then there’s Triumph, which has a thriving family of Bonnevilles, Scramblers and Thruxton parallel twins. And which, having just changed its Street Twin’s name to Speed Twin 900, now has a pair of retro roadsters named after the 498cc machine that appeared through the post-Second World War gloom to begin motorcycling’s first parallel twin era.

The Speed Twin was actually launched in 1937, and made an immediate impact, but the War’s outbreak two years later halted production. When the Triumph returned in subtly updated form in 1946, it dramatically proved that two cylinders could be better than one – inspiring rival firms to follow, and triggering a period of parallel twin dominance that would last for decades.

Its designer, Triumph’s charismatic boss Edward Turner, outlined the Twin’s advantages in typically forthright fashion. “It will run at higher revolutions than a single of similar capacity without unduly stressing major components,” he said. “The engine gives faster acceleration, is more durable, easier to silence and better cooled. In every way it is a more agreeable engine to handle.”

Few disagreed after riding the Speed Twin, which was matched by some singles in its top speed of just over 90mph, but not in effortless way it could cruise at 70mph. The pushrod-operated engine, which had a 360-degree firing arrangement (pistons rising and falling together), was softly tuned, with a maximum output of 29bhp at 6000rpm. Although there was some vibration, by single-pot standards it was smooth.

Turner had recently arrived from Ariel (where he had designed the glamorous Square Four), after that firm had taken over Triumph. He had announced himself by revamping Triumph’s single-cylinder range of 500, 350 and 250cc models with fresh styling and catchy new names: Tiger 90, 80 and 70.

Turner’s rare talent for both marketing and styling were again evident in the Speed Twin, with its evocative name and handsome lines. And the Twin’s lean, simple look was not misleading. It used essentially the same frame and forks as the Tiger 90, was actually slightly lighter than the 500 single, and its engine was slightly narrower.

It was the Speed Twin’s performance, though, that sent the testers of the day into rapture. “On the open road the machine was utterly delightful,” reported The Motor Cycle. “Ample power was always available at a turn of the twist-grip, and the lack of noise when the machine was cruising in the seventies was almost uncanny.” The magazine managed a two-way average of 93.7mph and a “truly amazing” one-way best of 107mph.

The journalist from rival magazine Motor Cycling was similarly enthusiastic in its January 1946 review. After collecting a Speed Twin from Triumph’s base at Meriden, near Coventry, where the factory had been rebuilt since being damaged by German bombs, he headed south-westwards towards Cheltenham, searching out twisty roads where the bike’s handling could be tested.

The Speed Twin did not disappoint, judging from the glowing report: “How can mere writing express that sense of mastery, that sympathy with the machine, that exhilarating impression of complete control which a healthy engine, hair-fine steering and super-adequate braking can combine to inspire?” He then took the Triumph for an off-road ride, where it again impressed, before reaching London as darkness fell.

My own Speed Twin test ride kept to the road and was distinctly brief in comparison, but despite that it was easy to appreciate the Triumph’s performance and light, easy handling.

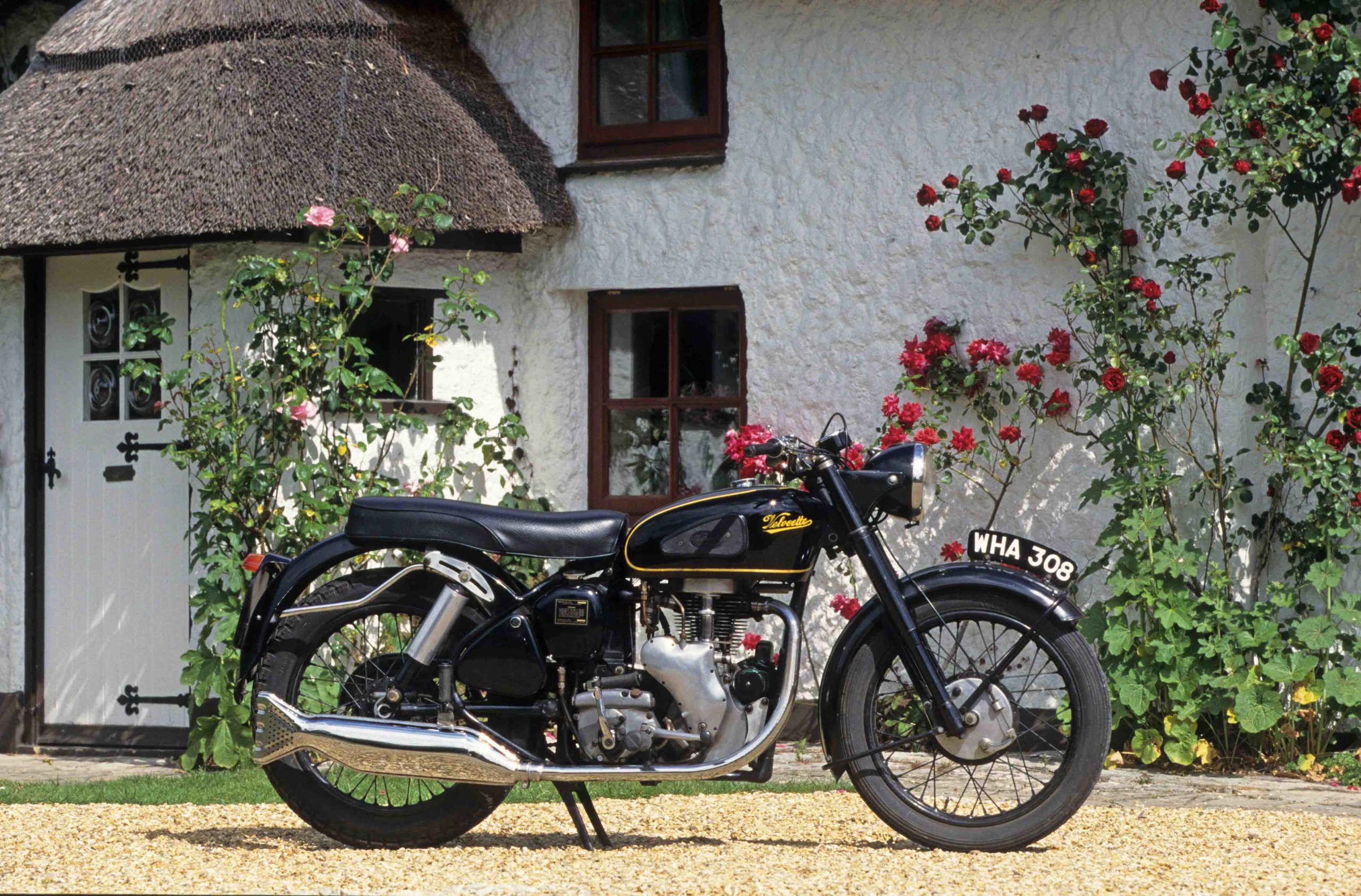

This bike was standard apart from handlebars that curved back slightly more than the originals. As a 1946 model it featured the telescopic forks that had been fitted that year, in place of the original girder design. Other post-War upgrades included a larger, four-gallon fuel tank and new magneto ignition.

The Triumph felt like a period piece as I heaved it off the tricky rear-wheel-mounted centre-stand, tickled the tiny, unfiltered Amal carburettor to get the petrol flowing, and gave a light kick to fire up the motor. The sound from the twin pipes was a lovely, mellow purr as I blipped the throttle. First gear went in with a graunch, but the controls were light, and once I was under way the right-foot gearchange was precise.

It didn’t take long to discover why so many riders had taken to the Speed Twin. Its half-litre motor was impressively smooth almost all the way through its rev range. The Triumph was enjoyably eager for such an old bike, its effortless low-rev response helped make it easy to ride, and vibration was not an issue at up to 60mph.

The Twin also handled well, at least for a bike with a hard-tail (unsuspended) rear end. At 167kg with fuel, the Triumph was light even by modern middleweight standards, and its ultra-low sprung saddle helped make control effortless. Its brakes were reasonably efficient, too, despite being simple drums.

The Triumph’s telescopic forks were hydraulically damped, and reckoned to give extra rear-wheel grip on bumpy road surfaces, compared to the girders, as well as improving the front end’s feel. Despite the lack of rear suspension, the Twin handled fine on reasonably smooth surfaces.

Even comfort was reasonable, thanks to the sprung saddle. Triumph introduced an optional sprung-hub rear suspension system two years later, in 1948, but it was disliked by many riders because it tended to make the bike weave.

The Speed Twin, by contrast, remained hugely popular for years, as did its sportier Tiger 100 derivative, whose extra power raised top speed to 100mph. In 1950 Triumph added the Thunderbird, with its bigger 650cc engine, in an attempt to stay ahead of rival firms who by now had twins of their own. The format would continue to dominate until the Seventies, when Japanese firms took over with their more powerful, smoother and better engineered fours.

And now parallel twins are back at the top of the charts. They cost less to produce than fours, triples, V-twins or boxers. Many are fine bikes, offering adequate performance and balancer-shaft smoothness, plus added character from irregular firing orders. But they’ll never match the impact of Triumph’s original, which transformed motorcycling in a way that only a select handful of bikes have done.

1946 Triumph Speed Twin

You’ll love: Its sweet power delivery and easy handling

You’ll curse: If you drop it trying to use the centre-stand

Buy it because: It’s an all time great that still rides beautifully

Condition and price range: Project: £6000 Nice ride: £9000 Showing off: £12,000

Engine: Aircooled parallel twin

Capacity: 498cc

Maximum power: 29bhp @ 6000rpm

Weight: 168kg with fluids

Top speed: 95mph

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage for daily news, features, interviews and buying guides, or better still, bookmark it. Or sign up for stories straight to your inbox, and subscribe to our newsletter.

I remember the Speed Twin had a rear Spring Wheel. The one in your article apparently doesn’t but they were a unique feature on most bikes.