It began as a “parts bin special” – cheaply developed and launched in 1994 with minimal fanfare. The first Speed Triple shared its 885cc engine and almost all other parts with other Triumph models. It looked fairly ordinary, in fact, with its low handlebars and single round headlight.

Three decades later, the Speed Triple has arguably been Triumph’s best loved model – having helped establish the firm as a maker of exciting, well-engineered bikes, and contributed hugely to its success. Revamped numerous times over the years, it has starred in Hollywood movies, frequently topped the firm’s sales chart, and spawned the smaller and also hugely successful Street Triple family.

Triumph was a very different company when that original Speed Triple was developed, shortly after building magnate John Bloor had revived the brand in the late 1980s. In 1992, the new Hinckley factory’s second year of operation, it produced barely 3000 bikes (compared to almost 100,000 last year). The firm was still committed to a modular format that reduced costs by sharing most components of bikes ranging from 750cc triples to 1200cc fours.

Depending on your view, the first Speed Triple was either the existing Daytona 900 sports bike with its fairing removed, or a sportier version of the Trident 900, the naked triple that had been the most popular of the original six-model range.

The Trident’s responsive, 885cc triple engine had been much praised, but that model was a simple roadster, with conservative styling and basic suspension. By contrast, Ducati had scored a big hit with its M900 Monster in 1993 by combining a softly tuned V-twin engine with aggressive naked styling and high-quality chassis parts.

The Speed Triple followed a similar format. Its liquid-cooled, 12-valve engine produced 97bhp and, apart from having a five-speed gearbox rather than a six-speed, it was identical to the unit that powered the Trident and Daytona. The bike’s steel spine frame was also shared with the other models.

But like the Monster, the Speed Triple had superior cycle parts: adjustable Kayaba suspension from Japan and a front brake combination of big twin discs and four-piston Nissin calipers. Its cast rear wheel held a fat, sticky Michelin radial tyre.

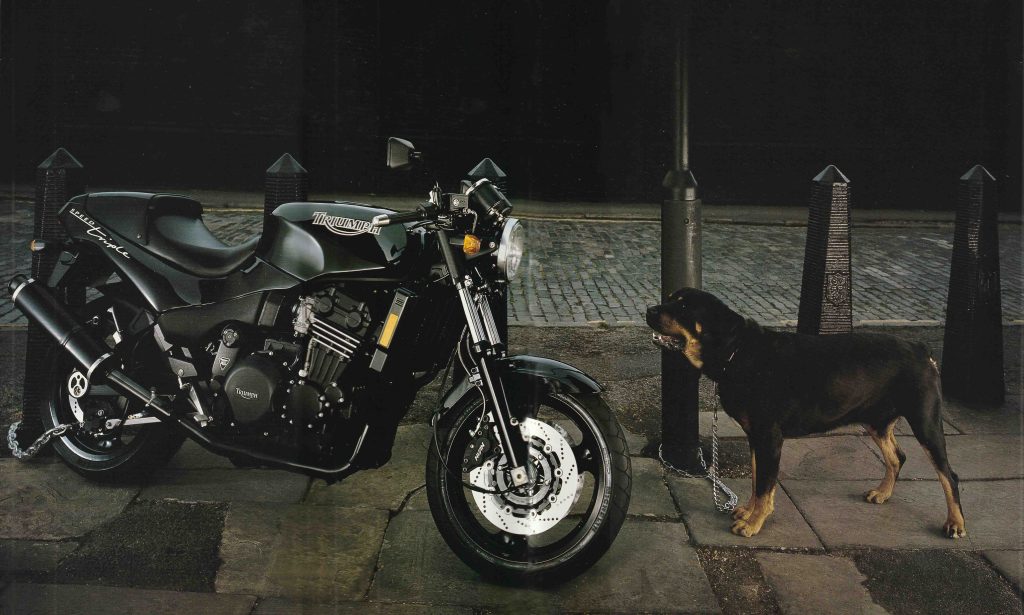

Styling was little more than stripped-down Daytona, with a single round headlight. But the retained low handlebars gave an aggressive look, highlighted by a memorable brochure image featuring a Rottweiler. And the Speed Triple name – inspired by the 1937-model Speed Twin that had been one of the former Triumph company’s greatest models – suited its café racer image perfectly.

That first Speed Triple struck a chord. Its zippy engine, responsive handling, and windblown riding position combined to give an impression of easy speed. Without a fairing and with much of its rider’s weight over the front wheel, it steered with appealing urgency and less of the top-heavy feel of other Triumphs.

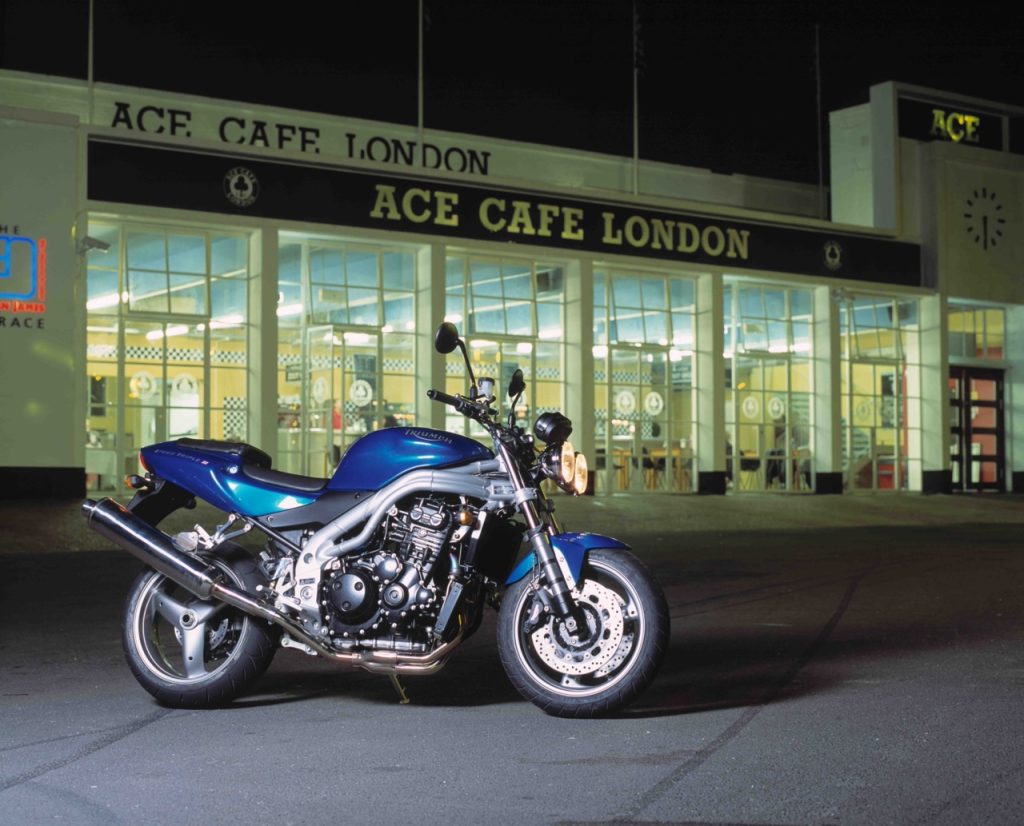

After borrowing a bike from Hinckley for a test, I rode to the site of the old Ace Cafe, legendary North London haunt of the 1960s Rockers, which had become a tyre depot. The leather-jacketed riders were long gone, and the traffic was much denser. But it was still fun to follow the classic lap down the North Circular Road, over the infamous Iron Bridge (scene of numerous fatal crashes), and back, just as the slick-haired Rockers did when attempting to return with a song by Gene Vincent or Eddie Cochran still playing on the juke box.

The Speed Triple was an excellent accomplice, and it proved a hit in 1994, becoming Triumph’s best-selling model – although in those early days that only meant 2683 were produced (including a small number of 750cc variants that were otherwise identical) out of a total bike production that by then had climbed past 10,000.

That was a good start, but the Speed Triple’s stroke of inspiration was still to come. By 1995, Triumph’s engineers and design team were developing the T595 Daytona – the 955cc, aluminium-framed sports triple that abandoned the modular format and would elevate the British brand to a new level of performance and sales on its launch in 1997.

In those days, much of Triumph’s development was based at the Northamptonshire workshop of John Mockett, the designer who had shaped many of the firm’s early models. At one point, while working on the Daytona, Mockett realised that the bike, with its distinctive tubular aluminium frame, looked good without its curvaceous twin-headlamp fairing.

“I said to Stuart Wood [chief development engineer] that we ought to do this without the bodywork,” recalled Mockett, who admired the aggressive streetfighter specials built by firms such as Harris Performance. “Stuart said, ‘No, we’ve got to get the 595 finished in time for the Milan show,’ so I said, ‘Okay, we’ll work on it in the other shed and see what we can do.’ John Bloor was always down there but we kept this thing secret from him.”

A few months later, Bloor arrived to inspect the finished Daytona T595. “We’d painted it and added decals by then and he said it looked alright – in fact he was very pleased. Then I said, ‘I’ve got this other one,’ and uncovered the naked bike. He looked at it and said, ‘F***ing hell, it looks like it’s been crashed!’”

The Triumph boss’s instinctive reaction summed up the naked triple’s appeal. The previous decade had seen the emergence of a biking subculture, especially in Britain, where Streetfighters magazine had become popular, highlighting the urban look that had grown up initially around twin-headlight Suzuki GSX-R750 and 1100 sports bikes whose fairings had been removed following a crash.

At that time, no major manufacturer had a model with comparable style. Bloor took some persuasion, but decided to put the naked triple into production alongside the Daytona. “He was so pleased with the Daytona that he accepted the other one on the back of it,” Mockett later recalled. “If it had been on its own he’d have turned it down, but the fact that it was on the coat-tails of the 595 appealed to him, because it didn’t need many extra bits.”

This new Speed Triple, initially code-named T509 (until, like the Daytona’s T595, this was found to cause confusion), retained its predecessor’s 885cc capacity but gained a new bottom end, intake system, and exhaust. It produced 106bhp, with strong midrange torque. The aluminium frame was identical to the Daytona’s except for being painted instead of lacquered, and it held similarly high-quality suspension, brakes, and a single-sided swingarm.

As with the original Speed Triple, Triumph introduced it with minimal fanfare, almost as an afterthought. I was one of two freelance journalists allowed to ride a T509 that was brought along to the T595 Daytona’s riding launch in Spain. A blast on local roads and on the Circuito de Cartagena race track confirmed that it had an addictive midrange punch, and that its handling, braking, and roadholding were excellent.

The T509 Speed Triple’s 1998 arrival was perfectly timed, its price was competitive, and it was an immediate hit, selling almost 2500 units to become Triumph’s second-most popular model, behind the Daytona. And its success proved lasting, helped by Triumph’s decision to enlarge the engine to 955cc in 1999.

By the turn of the millennium, the Speed Triple had become a cult model, its bullish style and performance highlighting that Triumph was now a serious player in the motorcycle scene. It was boosted by vibrant paint schemes, including an acidic Roulette Green and even more corrosive Nuclear Red (in reality a bold pink, as ridden by Natalie Imbruglia in the movie Johnny English). Speed Triple appearances in The Matrix (ridden by Carrie-Anne Moss) and Mission Impossible 2 (Tom Cruise) also boosted Triumph’s profile.

The firm did a good job of keeping the Triple’s essential look and character intact, while updating it every so often. One significant step came in 2002, when its output rose by 10bhp, to 118bhp, and its chassis was tweaked to quicken the steering and reduce weight. I also rode that model to the site of Ace Cafe, which, fittingly, had recently reopened as a nostalgia-themed motorcyclists’ meeting place; it continues to thrive to this day.

Another major update came in 2005, when a new, longer-stroke 1050cc engine increased maximum output to 128bhp. A new chassis contributed to a quicker, more agile bike that topped Triumph’s sales charts that year, with 8796 out of a total of almost 35,000. In 2011, Triumph was sufficiently confident to combine a sharpened chassis with non-round headlights – a controversial move that did not damage sales as some had predicted.

By this time, Triumph had ceased production of the Daytona 955i, leaving the Speed Triple as the firm’s sporting flagship. For 2012, the new Speed Triple R combined an unchanged, 133bhp engine with an upmarket chassis incorporating Öhlins suspension, Brembo Monobloc brake calipers, and a sprinkling of carbon fibre. It was exotic, expensive, and took the trademark Speed Triple blend of naked style and punchy performance to new heights.

Triumph was now facing a dilemma, as the arrival of Aprilia’s Tuono V4R sparked a new class of fierce “hyper-naked” machines: stripped-down superbikes created in similar fashion to the original Speed Triple but producing over 150bhp and backed by sophisticated electronics. The challenge was to keep the Speed Triple competitive, without losing its familiar charm and accessibility.

Triumph took a sizeable step in 2018, with an overhauled Speed Triple whose 1050cc engine contained more than 100 new parts, revved 1000rpm higher, and produced 148bhp, an increase of 10bhp. Alongside the standard model was an upmarket RS version with Öhlins suspension and a sophisticated electronics package incorporating traction control and cornering ABS.

Three years later came an even bigger leap, with an all-new Speed Triple 1200RS. Its engine was enlarged to 1160cc and produced 178bhp – slightly up on Aprilia’s latest Tuono, if not on Ducati’s outrageous 205bhp Streetfighter V4. This RS was also sharper and 10kg lighter, helped by a new aluminium frame.

Not every Speed Triple enthusiast was a fan of the new lean and mean naked superbike, or of the stylish, half-faired Speed Triple 1200RR that shares most parts and is even more aggressive and expensive. That’s not surprising. Both models have more than double the power-to-weight ratio of the Speed Triple that started the family 30 years ago.

The Speed Triple is a different class of motorbike now. Its evolution has taken it away from the raw, streetwise, firmly road-focused models of the past. These days, even the middleweight Street Triple 765R makes 120bhp – more than the T509 that did the most to earn the Speed Triple’s cult following back in 1997.

All of which means that the Speed Triple’s days at the top of Triumph’s sales charts are probably gone for good. Its status as one of the Hinckley firm’s most important and fondly regarded models, on the other hand, remains beyond doubt.

Absolutely beautiful article. A Speed had always been my dream bike and acquired an RR earlier this year!

A modern era big triple is a great thing to own. After four cylinders, a twin is a such a lumpy proposition. The “heritage” from the old Trident sets in stone the validity of the choice. Feels right.