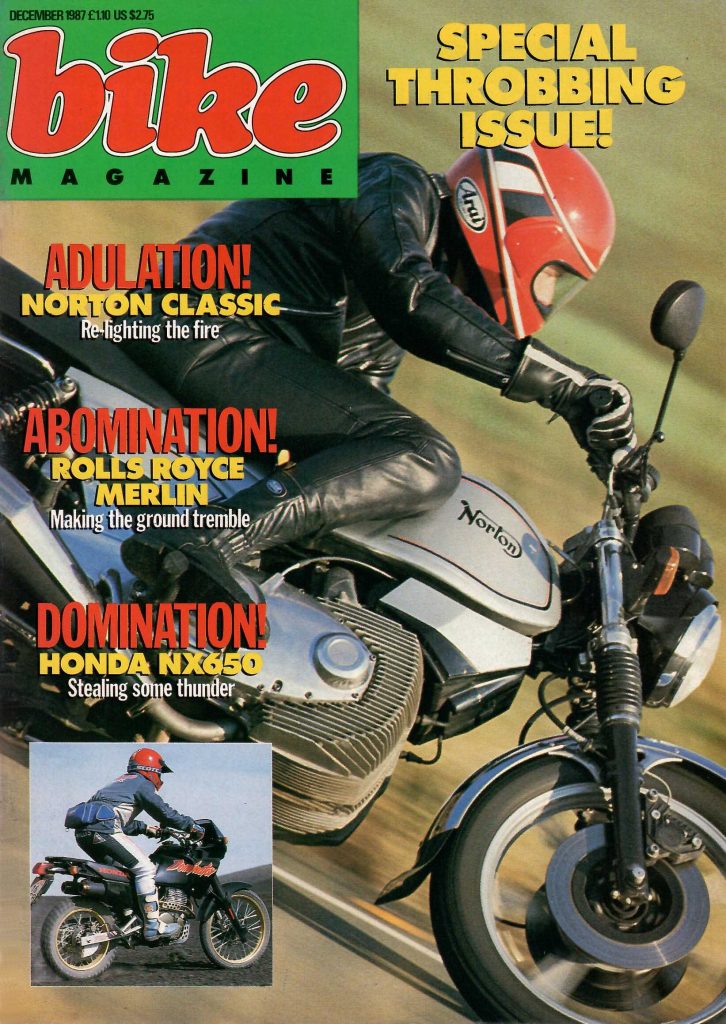

The launch of Norton’s Classic in 1987 felt like a landmark moment for the beleaguered British motorcycle industry. After more than a decade in development, the rotary-engined roadster was finally ready for production.

Riding the Classic through the gates of the factory at Shenstone that October to begin a first test was a thrill that remains vivid more than 36 years later. It really felt as though, after years of decline, one of the most famous British bike marques was leading a fightback.

Sadly for Norton, that’s not how things panned out. The British industry did fight back but it would be former rival Triumph that would lead the way, when that marque was reborn in 1991 with a range of modern, multi-cylinder bikes, before growing to become a leading global brand once again.

By contrast, Norton would endure a difficult few decades, involving numerous failed projects, takeovers and scandals, before recently regaining hope and respectability under the ownership of giant Indian manufacturer TVS. But along the way there were high points at Norton, too – and none greater than those generated by the rotaries.

The story of Norton’s Wankel-engined bikes was one for the romantics. It starred a low-budget racer that took on and repeatedly beat much better-funded rivals on the track, winning an Isle of Man TT as well as British titles. And it featured innovative, distinctive roadsters that briefly made Norton the star of motorcycle exhibitions, magazine covers, and showrooms.

The first of those was the Classic. Its origins were in the mid-1970s, when Norton engineers had begun developing a rotary-powered machine in secret and on a low budget, with the help of several UK police forces.

The rotary engine was not a new idea. German engineer Felix Wankel’s invention – with its triangular piston rotating around a central crankshaft, inside a figure-of-eight–shaped chamber – originated in the 1950s. It was already used by firms including Mazda and German bike manufacturer DKW. Suzuki’s RE5 superbike of 1975 had proved a short-lived failure, after which the other three Japanese manufacturers had abandoned their own rotary projects.

Norton’s painstaking development at least meant that when the Classic was finally considered ready, it worked well. Its air-cooled engine was 588cc (the way rotary engine capacity is measured is open to debate), and featured two chambers, equivalent to twin cylinders. Its maximum output was 79bhp, comparable with Honda’s best-selling CBR600F middleweight.

In 1987, the Classic’s chassis already seemed slightly dated, with its pressed-steel frame and twin rear shocks; by then the Japanese were using aluminium frames and monoshock rear suspension. But that wasn’t a major drawback given the Norton’s role as a roadster with nostalgic appeal, emphasised by its curly-script logo on a traditional paint finish of silver with black pinstripes.

On that first test back in 1987, I rode straight to a speed-testing facility, where the Norton impressed by reaching 125mph at the end of a half-mile, competitive with the CBR600F and other middleweights. It also handled and braked well, and revved with eerie smoothness and a rasping exhaust note that contributed to an engaging character.

At the time, the Classic’s overall performance felt similar to that of BMW’s 1000cc, four-cylinder K100 – more than respectable for a new model from a small firm. The British bike was smoother and handled better; the German one was stronger at low revs and more economical. The hand-built Classic was also more expensive, but its status as a limited edition model of which only 100 would be built helped ensure that all were quickly sold.

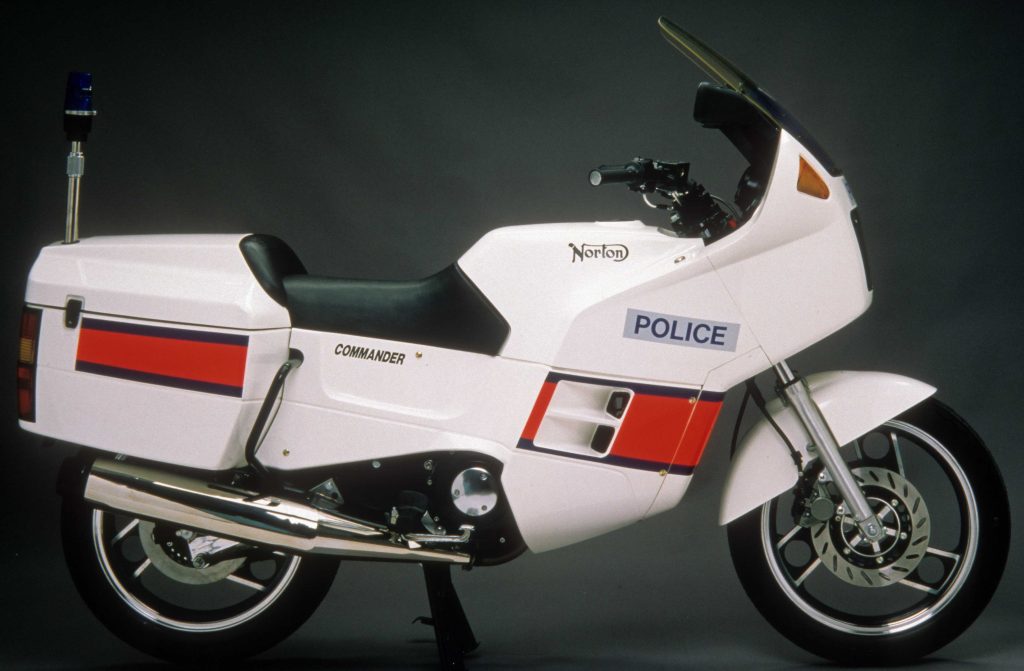

Norton swiftly followed the Classic with a dedicated police variant called the Interpol 2, and with the Commander, a sports-tourer that held a liquid-cooled version of the 588cc engine beneath a full fairing. The roadsters combined to get Norton’s rotary revolution off to a promising start, and momentum grew with what began as a low-key sporting sideline.

While developing the roadsters and police bikes, a small group of employees led by engineer Brian Crighton had also spent time (and some of their own money) building a prototype that held a tuned engine in a cut-down standard steel frame. After having the bike timed at 170mph, they persuaded Norton chairman Philipe Le Roux to finance further development, including commissioning an aluminium frame from local specialists Spondon Engineering.

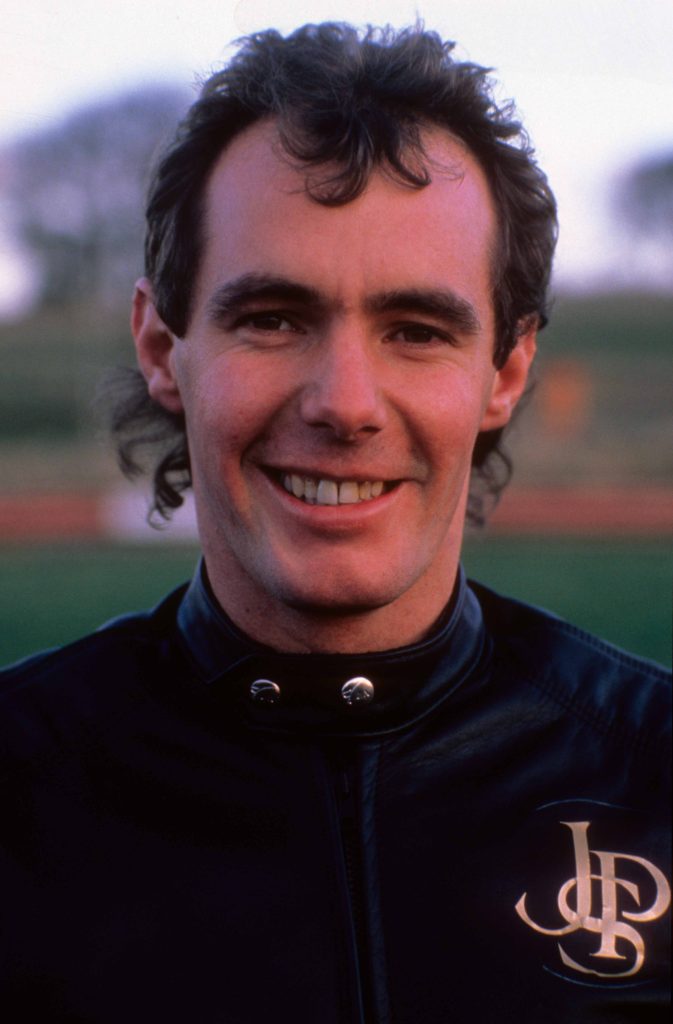

The resultant racebike produced 135bhp, spat flame from its exhaust in spectacular fashion, and delivered results that were first encouraging, then astonishing. Ridden by a Norton employee named Malcolm Heath, the rotary began winning races at National level in 1988. The following season, with new riders Steve Spray and Trevor Nation at the bars, and in black JPS cigarettes livery, it won two major British championships and set a string of lap records, to the delight of a vast television audience and moist-eyed crowds throughout the land.

Norton took advantage by developing a roadgoing sports model, the F1, which was launched in 1990 and echoed the racer as closely as possible. Designed by London-based agency Seymour Powell, the F1 incorporated smooth, all-enveloping bodywork. Its riding position was sporty, with wide clip-on handlebars and a single seat.

It was powered by a Commander engine, turned back-to-front and uprated with the five-speed gearbox from Yamaha’s FZR1000. In roadgoing form, the 588cc unit couldn’t approach the brute horsepower pumped out by the snarling rotary race bike, but it produced a respectable 95bhp. Its Spondon-built twin-spar aluminium frame was a stronger version of the racebike’s, with steering geometry revised to aid stability. Sophisticated WP suspension, Brembo brakes, and Michelin radial tyres completed an upmarket package.

The F1’s power and weight figures were similar to those of a typical Japanese 600, and so was its 145mph top speed. On the road, the rotary felt very different, thanks to its smoothness, generous midrange torque, and unique exhaust note. For a sportster, the F1 was fairly comfortable, and its rigid frame and excellent suspension gave surefooted handling. But there were rough edges: The Norton was thirsty, and its engine snatched at low revs and was prone to overheating – a common rotary issue.

The hand-built, limited-production F1 was also expensive, a drawback that Norton addressed a year later with the slightly cheaper F1 Sport, which used simpler bodywork and lower-spec suspension, wheels and brakes. That meant the F1 Sport felt a little less sophisticated during my test ride but it was still enjoyably quick and nimble, and its motor had a smoothness and a crisp midrange response that most conventional middleweights couldn’t approach, backed-up by an exhaust note that changed from a low-rev burble to a memorable rasp at full chat.

Town speeds had been the original F1’s Achilles heel due to its poor running at low throttle openings. Adopting the Commander’s carburettors had solved that problem, and the Sport trickled happily through traffic. At least it did until one particularly slow stretch, after which it suddenly overheated violently with a cloud of steam that embarrassed its rider and amused passing pedestrians.

Norton’s rotary revival fizzled out in similarly disappointing fashion, but not before more improbable racing success. In 1992, Scottish ace Steve Hislop rode a white-finished rotary to a famous victory in the Isle of Man Senior TT, beating Yamaha-mounted Carl Fogarty by barely four seconds after an epic high-speed battle. Two years later, another Scot, Ian Simpson, won the British Superbike title riding for a private team run by Crighton, who had left Norton after a disagreement.

By this time the company was in disarray. A follow-up sports bike, the F2, was displayed at the Birmingham show but never produced. Norton’s new Canadian owners abandoned the rotaries, leaving the factory to make only a small quantity of spare parts. Several former directors would eventually be convicted of financial irregularities, and hundreds of enthusiast shareholders lost the money they had invested.

There would be more lows during Norton’s next, turbulent quarter-century, starting in 1998 with the Nemesis, a hopelessly optimistic 1500cc V8 concept bike that never reached production, and ending with the firm going into administration in 2020, and with former CEO Stuart Garner’s conviction for pension fraud.

The investment of new owner TVS has resulted in Norton reaching its 125th anniversary this year with much to celebrate. It is producing a revamped range of retro-styled Commandos and powerful, modern V4s in a new factory in Solihull, near Birmingham, and has embarked on an electric bike project that hints at a high-tech future. But Norton still has a way to go to recreate the excitement generated, more than three decades ago, by the rotary-engined Classic and its flame-spitting racetrack derivatives.

What a fascinating, little known Rotary history.

Didn’t Mazda win the Le Mans 24 with a Rotary ?