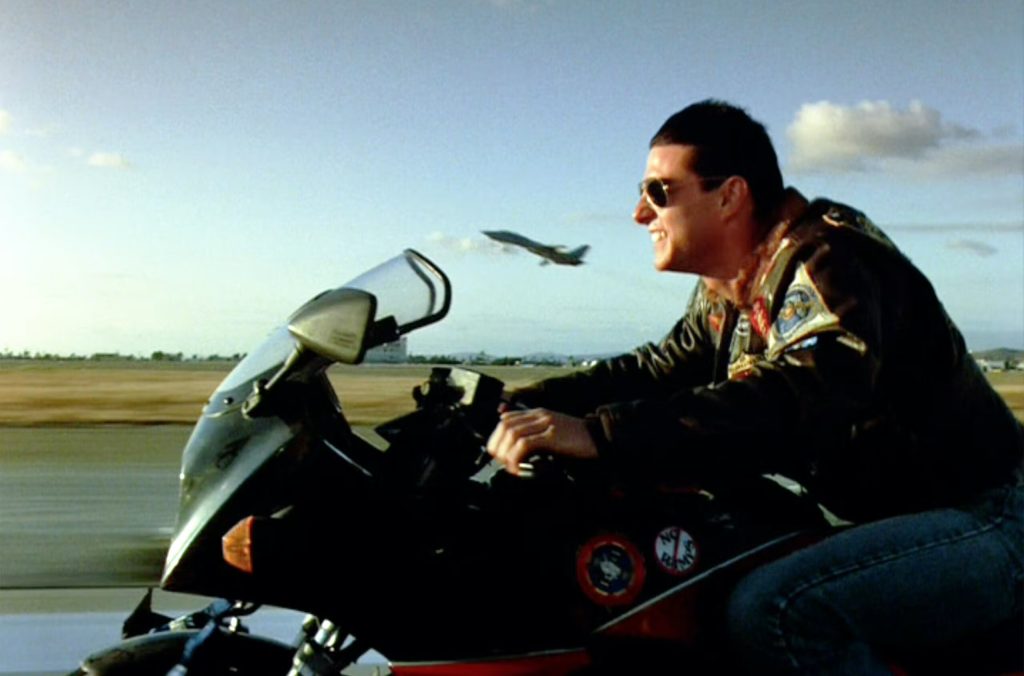

Sixteen minutes into Top Gun on its opening weekend in May 1986, some 2 million people met the Kawasaki Ninja for the first time.

When a grinning Tom Cruise in Ray-Ban aviators and a flight jacket strafed a Navy runway alongside an F-14 Tomcat, the scene catapulted Kawasaki’s new superbike into popular culture in a way only a box-office hit can. Just as all photocopies were Xeroxes and all tissues were Kleenexes, from here on, all fast motorcycles would be known as “Ninjas.”

Of course, sensationally fast, open-class (or 750cc and above) superbikes already existed prior to 1984, including the Suzuki GS1100E, the Honda CB1100F and six-cylinder CBX, and Kawasaki’s own GPZ1100. These air-cooled machines basically incorporated decade-old engineering, whereas the 908cc Ninja uniquely featured a next-gen DOHC 16-valve inline-four engine to go with its novel overhanging steel truss frame and grand prix–inspired bodywork. Its liquid cooling – a feature shared with Honda’s contemporaneous and smaller VF750F Interceptor – helped reset the game board for motorcycles by letting the mills run cooler and more powerfully under hard conditions. And, thanks to these engines’ tighter internal tolerances and more precise carburation, it meant sport bikes could evolve to meet increasingly strict emissions regulations.

By this time, “superbikes” had already been on the road since 1969. That’s when Honda launched the sophisticated overhead-camshaft CB750 Four and Kawasaki debuted the H1 Mach III two-stroke triple. Seemingly every year after, displacement, power, and performance increased, until these screaming machines could produce astronomical quarter-mile times. The 1980s brought new-wave music, big hair, aerobics videos, spandex, and even further superbike performance, with machines now cloaked in plastic body panels and looking, for the first time, like their grand prix counterparts. The “crotch rocket” form we know today was born.

Referred to internally as the GPZ900R, the new-for-1984 Ninja also furthered Kawasaki street-bike tech by using its engine as a stressed frame member, a small-diameter 16-inch front wheel (later upsized to 17), and a fork with air-assisted springs, progressive damping, and anti-dive circuitry for improved chassis stability under braking. Best of all, the new Ninja was the hardest-hitting big Kawasaki yet, credited with savaging the quarter-mile in 11.18 seconds at 121.65 mph.

Its name was dreamed up by Mike Vaughan, director of marketing for Kawasaki Motors Corporation (KMC) in America. While serving in the Army, he’d lived in Asia and learned about Japanese mythology and the lore of the ninja warriors, who were celebrated for their wiliness and strength.

“Back in 1975, I was in Minnesota working on KMC’s snowmobile business, and I decided that ‘Ninja’ would be a great name for my sailboat – quiet and stealthy,” he recalls. “At the time, we were working with an outside designer by the name of Al Shimasaki. Al kind of designed how the logo would look, cut it out of blue vinyl, and affixed it to my boat.” By 1979, Vaughan had sold the boat and moved to Southern California. Kawasaki’s product planning department was considering formally naming its upcoming line of air-cooled GPZ sport bikes and he immediately thought, “Ninja!” “Ultimately, it took a decade and a lot of effort for the name to get from the idea stage through all the corporate channels here and in Japan, but in the end it was perfect.” The Ninja name first appeared in the US market only, then expanded internationally.

The new warrior debuted in December 1983 at a media event at Laguna Seca Raceway in California. It was the usual kind of grubby morning in Monterey, cold and foggy. Not quite raining, but everything was damp. This meant hazardous, slippery conditions for the journalists racing around the track on two wheels – especially through exceedingly fast “old” Turn 2. On the track’s original nine-turn layout, Turn 2 was notorious for being the spot where, sadly, a rider had died in a 250 GP race a few years earlier. Adding to the pressure was a stack of international bike journalists who had all developed the eye of the tiger once 1983 AMA Superbike champion Wayne Rainey was unleashed to ride with them. Peer pressure and performance anxiety, check!

Motorcycle journalists were primarily concerned with relaying to their audience the sensory experience of piloting the new $4599 Ninja, less so with the question that ordinary sane people might ask, which is why someone would want to ride one at all. Answer: Superbikes feed the senses and urges that helped our passage through the ages. Aggression and control; risk and reward.

Luckily, I’d gained a spot at the launch, working for an Australian magazine. Straddling the Ninja and cradled by its shallow “bucket” seat, I rocked the machine off its center stand and pulled the enricher lever for the quartet of racing-derived semi-flat-slide carbs – Kawasaki’s compromise between progressive round slides that control air volume through the carb in a way that is better for street bikes and flat racing slides that are basically on-off switches. I turned the ignition and tagged the start button; the black-finished engine growled through the airbox located between my legs and out its dual black-chrome exhausts (bright chrome was history when the Ninja arrived). A unique counter-rotating balancer, geared off the forged-steel, five-bearing crankshaft, helped quell engine vibration, but the buzz of the idling motor still permeated all touch points, even the sides of the humpback tank where knees interface. Just touch the throttle and, as Henry Frankenstein screamed, “It’s alive!”

The GPZ900R’s low-set handlebars and rear-set foot controls invite a sporty riding posture, crouched out of the wind behind a narrow fairing in an attack position. This has but a single purpose – going fast. As every Mario Andretti knows, speed delivers a rush we can’t get any other way, at least on land. And in doing so, it heightens our life experience. But unlike in a sports car, hurtling along on a bike, you’re 100 percent “in it” – exposed and vulnerable, bracing in the wind blast, glimpsing the asphalt skimming beneath our knees in the turns, all senses alive.

“Well, it’s one louder, isn’t it?” mused guitarist Nigel Tufnel in This Is Spinal Tap, about his amplifier’s volume controls calibrated to 11 instead of the usual 10. “You see, most blokes, you know, will be playing at 10. Where can you go from there? Where?” Onto the Laguna Seca track. On the new Ninja.

Entering the circuit past the cresting Turn 1, a twist of the throttle sent the Ninja furiously ahead. With its rider clutching the handgrips, tucked behind and focusing through the fairing bubble, knees clenched against the tank and feet locked against the chassis, the Ninja banked through Turns 2 and 3 and charged uphill to Turn 4, a quick left on the backside of the course. En route, the tach needle flew to the 10,500rpm redline and the six-speed gearbox caught fourth with a mere tug of the clutch lever and an upward nudge of the gear lever. Vaulting past 100 mph, the shapes of oaks, fences, a bridge, and earthen banks rushed into peripheral view, whisked past, and then were forgotten as new images arrived. It was a fast-paced video game, and oh-so-real.

Although there wasn’t room for top-end testing at Laguna, a later magazine test reported a 151-mph top speed for the bike. That’s fitting, because the Tomcat as seen in the ’86 film lifts off at 140 knots (161 mph) – only fractionally quicker.

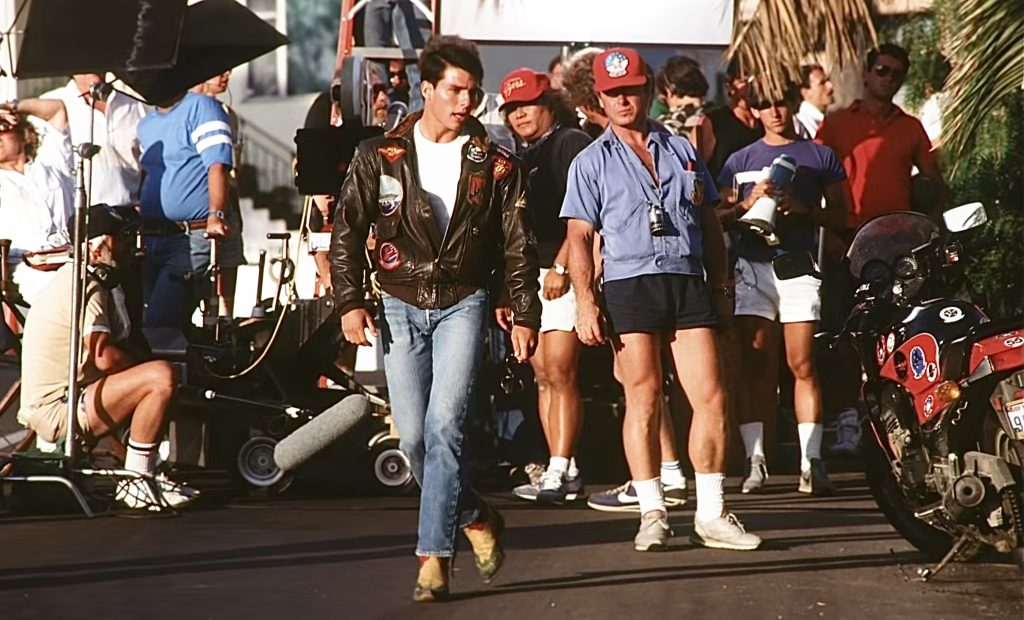

As the DeLorean did in 1985’s Back to the Future, the Ninja serendipitously struck gold in 1986. Or, more accurately, gold struck the Ninja when it landed in the memorable Top Gun scene. “One day, I got a random call from one of the film producers,” Vaughan recalls. “It was late in production, and we didn’t know much about it. Tom Cruise also wasn’t a big star yet – Risky Business was his biggest role so far. The producer asked for three Ninjas, but we had been burned so many times by production companies that wouldn’t return bikes, I had adopted a policy of selling them units at dealer net.” Still, the producer insisted Kawasaki give them the Ninjas because the company would get “great exposure.” “But then, they all promise you that,” says Vaughan. “Finally, when he threatened to go to Honda instead, I said, ‘Fine, I’ll give you their number.’”

After hanging up the phone, Vaughan mentally shelved the idea – at least until the producer called back a week later and agreed to buy the bikes. “I sold him three Ninjas for something like 15 per cent off,” Vaughan says. “I later heard that the Ninjas had been appropriated because Cruise insisted on it.”

Following the sale, Vaughan considered it a business deal closed, and he heard little more about the movie until it premiered. Then, big surprise! “As ‘punishment’ the production company took the Kawasaki name off the gas tank but left ‘Ninja’ on the side panels,” he says. “We were fine with it because at that point, getting the Ninja name noticed was more important than ‘Kawasaki,’ and we figured people interested in the bike would find out very shortly who made it.” Luckily for Kawasaki, though, Top Gun became the year’s highest grossing movie and has since grossed an estimated $357 million worldwide. That’s a lot of eyes on the Ninja.

A year after the Ninja 900R debuted, Kawasaki launched an all-new Ninja 600R, a smaller super-sport. Featuring similar liquid-cooled engine architecture and 35 per cent less displacement (592cc), the so-called Baby Ninja was also significantly lighter (478 pounds versus 567 pounds, or 217kg vs 257kg, respectively) and cheaper to insure. That was important for the new and younger riders that Kawasaki hoped to attract. Its press launch wasn’t international, but it again focused on track sessions at Firebird Raceway in Arizona. There, the small Ninja proved plenty capable.

Retailing for $3299, the Ninja 600R was the first Kawasaki with a perimeter frame, which used rectangular steel spars that splayed from the steering head around the sides of the engine, wishbone-like, to join the rear suspension swing-arm pivot. Virtually all top-line sport bike and motocross frames use this general layout today, although the material is often aluminium. Besides utilising relatively straight, triangulated tubing for structural stiffness, the Ninja’s new-order frame helped improve mass centralisation and rider position on the bike. Like the Ninja 900R, the 600R had an anti-dive fork with progressive damping, triple disc brakes, and the same tidy 56.1-inch wheelbase.

With its smaller displacement, the GPZ600R was smooth and rev-happy. A venomous lightning bug out of its bottle, in Arizona it spent the day gobbling up area roads and darting around Firebird’s road course on its compact 16-inch wheels. That night, it hit the drag strip in a dramatic eliminator-style contest among journos.

Following these debuts, the Ninja name continued uninterrupted to the current Ninja ZX-6R and Ninja ZX-10R. Along the way, models ranged from the little 249cc learner Ninja 250R (1986–2012) to the maniacal 1441cc Ninja ZX-14R (2006–2020). Ninjas have won the Daytona 200 five times and earned four AMA Superbike and eight World Superbike titles. Today, the lineup contains nine Ninjas, from the 399cc Ninja 400 ($5199) to the track-only 998cc Ninja H2R ($56,500) boasting a reported 310 horsepower.

Fast-forward 36 years from ’86 and the new Top Gun: Maverick movie also features a Ninja, again with Cruise aboard at some imaginary Fightertown. Now, as then, it’s the top current Kawasaki street model – in this case, a blown H2. Debuting in 2015, the machine is worth noticing because it’s a 998cc four-cylinder hyperbike built around a tiny aerospace-grade 130,000-rpm centrifugal supercharger that stuffs 20.5 pounds of boost into the engine. That produces over 200 horsepower at 11,000 rpm. Frankly, it makes the first GPZ900R Ninja seem quaint by comparison. Oh, and the $30,500 H2 weighs 525 pounds (238kg), rendering a power-to-weight ratio well clear of a $3.3 million Bugatti Chiron.

The H2 launch was followed by the global launch of the Z H2 “hyper-naked” model at Las Vegas Motor Speedway in early 2020. Based on the Ninja H2 but eschewing bodywork (hence the segment’s “naked” moniker), the Z H2 offered nearly all the performance of the Ninja H2 together with a more comfortable riding position. The appetiser was hot laps on the road course situated outside the 1.5-mile tri-oval. And what do you know, it was a chilly winter day. What is it with Kawasaki launches? The morning air temperature was 42 degrees (around 5C), and blasting around the 14-turn road course became a finger-numbing, teeth-chattering experience (wind chill 24 degrees at 100 mph). Of concern wasn’t the bike’s power, but how the Pirelli radials were going to get it to ground through contact patches about the size of a credit card.

Thanks to their high silica content for cold grip, they did, and lapping progressively faster, confidence in the machine grew. The handling was spot on – linear, intuitive, and predictable. For a 529 pound (240kg), wildly powerful motorcycle, it seemed almost telepathic in pointing where its pilot wanted – whether that was trail-braking into a hairpin turn or banging through upshifts until hell wouldn’t have it. As we’ve seen with chunky CUVs like Porsche’s Cayenne Turbo, big doesn’t necessarily mean bumbling, as it did in the 1970s. Much credit is due to the Ninja family’s modern technology, including a five-axis Bosch inertial measurement unit (IMU) and impressive onboard ECU firepower that enables launch control, traction control, throttle sensitivity, power delivery, ABS, and more.

So, as exciting as the first GPZ900R was at the time, the Z H2 – or any of the four-cylinder Ninjas now available – would absolutely destroy it. Time and technology march on; Tom Cruise turned 60 this year and the F-14 took its last flight for the Navy in 2006. However, old soldiers like that original Ninja never die. They just become collectable.

This story was first published in the Hagerty Drivers Club Magazine, in the US.

Read more

Forty years of Honda’s trend-setting turbo bikes

Ten ’80s motorcycles that crank out fun without costing road tax

Royal Enfield’s Continental GT was the right bike at the wrong time

They took the Kawasaki name off the tank as punishment for having to pay for the bikes? That’s miniature genitals, right there. I wonder how many other people were put off buying one because 1. Ninja, as defined by Monty Python is a “tinny word” which denotes inferiority; or 2. Kung Fu concepts, especially as in the recent dreadful movie, “Enter The Ninja” were ten years old by then and considered fit only for eight-year-olds. Or that in the movie, Tom Cruise was seen in some unfortunately designed cowboy boots that made him look like he was wearing his sister’s heels. A

It’s hilarious that this article contains a picture clearly showing them. Factually, the bike was extremely good, though, had I bought one, the first thing to come off would be the Ninja labels. It’s very telling that there are incredibly few of these changing hands at auction, suggesting they are not as “classic” as they might have been, had they not been saddled with an unfortunate media reference. I note that the Z1 and Z900s generally are considered the grandest of classics, never having been weighed down by a model named “Chips.”