One of the worst side effects of digital photography is the additional step that it takes to bring your photography into the real world. If you’re not diligent in saving files or inspired to make prints, whole catalogues can be lost to the annals of time. Without physical negatives, plenty of my photos that grace this website no longer exist beyond a line of code in our system. It’s a major bummer.

And I’ve only been shooting for six years. Imagine a career photographer’s photo storage conundrum. I have plenty of colleagues who squirrel their stuff in hard drives that look like bank safes. That’s all well and good, but what happens if, one day, that drive doesn’t turn on? The world will have gained one more paperweight.

The Revs Institute in Naples, Florida, gets it. This repository of automotive history and memory includes over 120 archival collections, 26,000 books, and 200,000 magazine and journal issues. Even better, they are open to researchers and the public by appointment. And Revs’ extensive photo collection is available online through the Revs Digital Library (RDL) – presently with 700,000-plus images and counting.

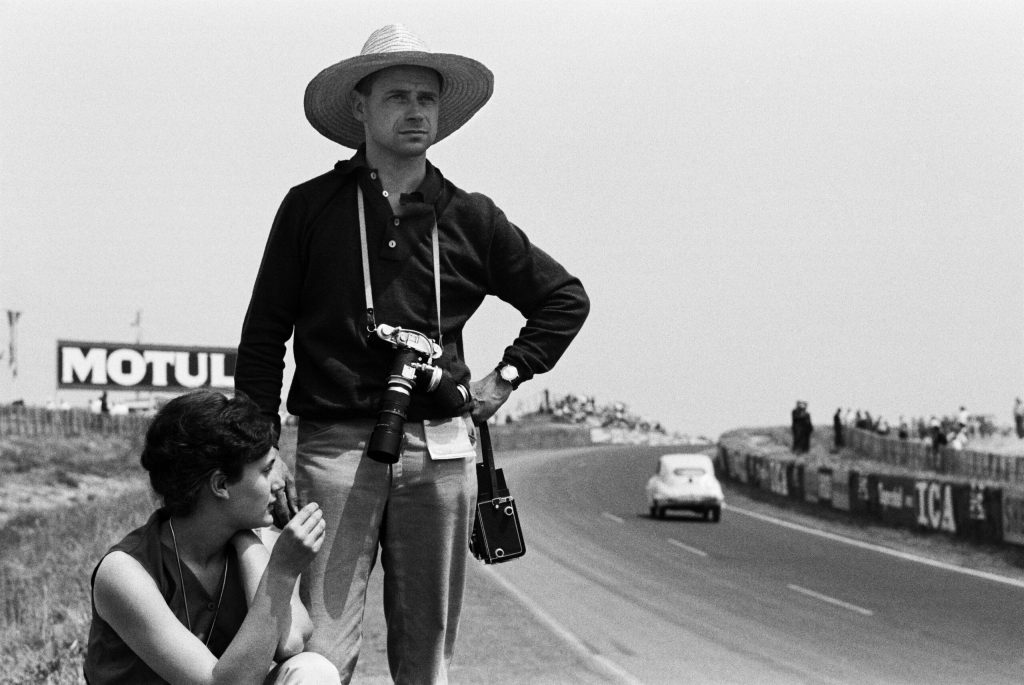

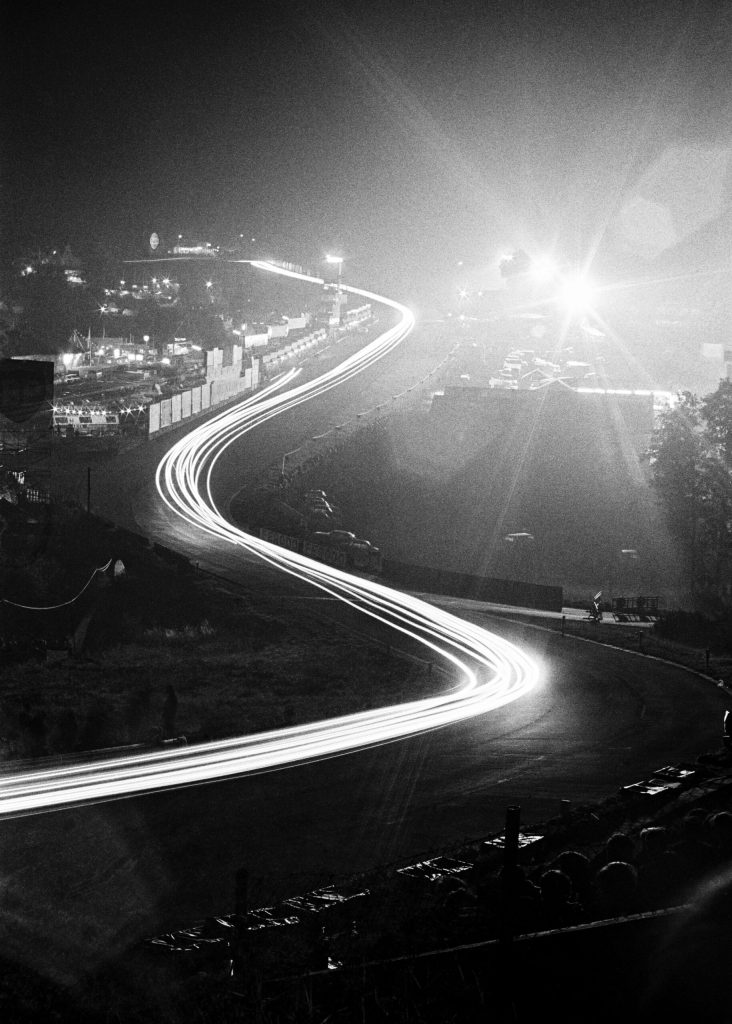

The Institute is currently in the process of digitising another 2 million shots, including images by the recently acquired André Van Bever Photography Archive. “Throughout his career, André Van Bever chronicled motor racing history, from Juan Manuel Fangio in 1949 to Niki Lauda in 1975, making him one of the most renowned visual witnesses of postwar motorsport,” said Scott George, Curator of Collections.

Preservation of information might be the most important thing on this planet. For my money, photos are artifacts right up there with the Declaration of Independence, the Parthenon, and Sir Stirling’s helmet. Luckily, the Revs Institute recognises the importance – and the impact – of preserved shots within the automotive space.

“Caring for photographs is a real responsibility, because by and large, they are unique,” said Miles Collier, founder of the Revs Institute, in a press release. “They are one image taken by one photographer, at one moment in time, and if something happens to that image, that moment in time is forever lost.”

Van Bever was born in Brussels in 1922. His career in photojournalism began at 18 years old when he covered a motorcycle race at the Bois de la Cambre in Brussels as a favour for a friend.

In 1947, he began a 28-year stint as the official photographer of Belgian newspaper Les Sports. Throughout his career, he was assisted by his wife, Nicole Englebert-Van Bever.

“I realise now that he had an artistic side, but he didn’t [realise it],” Englebert-Van Bever told Revs. “Although, I found there is an element of research in every photo. He saw himself as more of a photojournalist who was always under pressure. He wasn’t aware of his artistic side in my opinion.”

The couple became close friends with many of the drivers, especially fellow Belgians Paul Frère, Olivier Gendebien, and Lucien Bianchi, among others.

Van Bever’s negatives will be cleaned, logged, and processed over the coming year, then uploaded to the RDL and tagged so that the photos are searchable by scholars and the general public. (The entire RDL can be found at library.revsinstitute.org.) Until then, check out a sampling of Van Bever’s remarkable work in the slideshow below.