Homologate: Verb; Approve (a car, boat, or engine) for sale in a particular market or use in a particular class of racing.

Forty years ago, the world was mad for rallying. The once-genteel motorsport held on public roads and geared toward endurance and precision had evolved into outright speed contests. Hundreds of thousands attended major events like the Rallye Monte-Carlo – which, in turn, attracted carmakers that were eager to use the sport to sell cars.

That era, from the early 1980s to mid-1990s, spawned some of the most fascinating competition weapons ever produced.

We’ve gathered three here to prove that point. This trio covers the wide breadth of machinery from the era, each one imbued with character from their countries of origin. From Germany, we have a full-blooded factory rally car, a 1985 Audi Sport Quattro S1 – this machine actually a veteran of the 1985 RAC Rally in Wales. The Peugeot 205 T16 is the street version of the French company’s 1985 rally racer. Though it started life as a front-engine economy hatchback, the T16 is a mechanical Frankenstein with a mid-mounted turbo engine and four-wheel drive. And finally, the 1994 Lancia Delta Integrale Evo II is the refined hot hatch of the bunch, a supremely compelling canyon carver that shows how the mad Group B specials of the early 1980s evolved as a result of rule changes that further commonized rally machines with ordinary production cars.

These rare gems of racing history – only a few Audi Sport Quattros exist in private hands – were sourced and provided by AI Design, a shop in Tuckahoe, New York, outside of New York City. To stretch their legs, we headed to the Wilzig Racing Manor two hours north of New York City. Motorhead Alan Wilzig built a private racetrack at his farm and generously let us loose on the track and trails nearby.

This story has several origins, including the start of the World Rally Championship in 1973 and the subsequent set of regulations introduced for the 1982 season called Group B that, for a short period, made rallying more popular than Formula 1. An argument can be made, however, that we would not be here except for one man’s embrace of two pieces of tech that were getting a lot of attention in the late 1970s: turbocharging and four-wheel drive.

In 1972, Ferdinand Piëch, who inherited the technological genius of his grandfather, Ferdinand Porsche, was probably still basking in the success of the Porsche 917. That car, which was developed while Piëch was head of Porsche Motorsports, was the first Stuttgart stallion to nab the overall win at the 24 Hours of Le Mans, in 1970, thus becoming the dominant sports-prototype racing car of its era. Piëch’s reward was a job at the special project department at Audi. He was just 35 years old.

In the late ’70s, Piëch recognised that an ongoing R&D project, a compact four-wheel-drive system, could vault the brand’s stature. He further realised that the best showcase for the feature was rallying, which raced production-based cars on dirt and snow – two surfaces where four-wheel drive would have a huge advantage.

Audi introduced the new drivetrain on the 1981 Audi Quattro, a coupe based on the stodgy Audi 4000 sedan. The Quattro also had another novel feature bolted to the five-cylinder engine: a turbocharger.

The Audi, known informally as the Ur-Quattro, had fender bulges at every corner to accommodate its wider suspension and larger tyres. Car and Driver called it “a landmark car.” In 1981, Audi’s fresh rally race team suffered the usual new-car mechanical problems that often forced it to retire, but the Quattro won three times – including the Rallye Sanremo in Italy, with the doyenne of drift, Michèle Mouton, behind the wheel.

Alas, Audi’s technological advantage coincided with the new Group B regulations that came into effect in 1982. The new rules smashed rally’s traditional close connection to production cars by folding into one class several previous classes that allowed some pretty exotic machinery. For example, just one rung up on the new ladder was Group C, about to be dominated by the all-conquering Porsche 956, so we’re talking the Pentagon-budget, moonshot end of the racing spectrum. The French bureaucrats who run the Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA), the international body that governs the rules in much of the big-time European series, also slashed by half (to 200) the number of stradales, or street-legal cars, required for Group B approval, or homologation. That cut the participation cost for carmakers – at least, initially. Furthermore, manufacturers were allowed to build special one-offs, called evolution cars, in batches of just 20. There were no limits on engine placement or the materials used, and only a basic minimum weight based on engine size that meant turbocharged engines were favored. While the heroic Walter Röhrl in a more reliable Opel won the 1982 WRC drivers’ championship, Audi took the manufacturers’ crown, hinting at what was to come.

What followed was the onslaught of the lightly regulated Group B machines. Lancia, Peugeot, Renault, Citroën, Ford, and even British Leyland’s MG division entered new cars, some with mid-mounted turbocharged engines, most with four-wheel drive. Horsepower galloped higher as did the speeds, which drew more crowds. Photographs and videos of the Group B era show a sea of people standing in the roads and scrambling for safety right as the cars punched through. “The only thing that scares me,” said Röhrl at the time, “is the crowds.”

The danger amped up the publicity. A win brought global prestige, creating a cyclone feedback loop that invited more car-company money to produce faster cars and more promotion, which attracted yet more spectators. Drivers of the factory teams, highly funded by boards of directors who demanded returns on their investments, faced huge pressure and took more and more risks.

The wheels came off in 1986. An estimated 300,000 people attended the Rally de Portugal, and swarms lined the route. When a Ford RS200 spun off the road, it plowed into the spectators, killing three and injuring dozens. Two rounds later, at the Tour de Corse on the island of Corsica, Finnish driver Henri Toivonen, in an extremely quick Group B Lancia Delta S4, slid off the road and flipped into the forest. The car caught fire, and Toivonen and his co-driver, Sergio Cresto, died. High speeds best confined to closed circuits rather than uncontrolled public roads were blamed, and Group B was banned for 1987.

The Group B cars, however, and the subsequent models inspired by the era remain. Today, they’re commonly called “homologation cars” because they existed primarily for racing. Just like the coveted factory-special drag cars of the ’60s, these homologation cars are the upcoming prized models fueled by the next generation of collectors who grew up watching these cars in thrilling videos and driving them in video games. They’re also now recognised as technological proving grounds during a fast-evolving 15-year period that stands in stark contrast to the moribund 1970s.

1985 Audi Sport Quattro S1 E2

The odd little five-cylinder that lives in the wrong place lights with an unexpected WHOMP! It idles at a frenetic 2,000 rpm that vibrates the whole car, magnifying the deep-throated exhaust cacophony. Yet the steering and clutch are surprisingly light. To familiarise myself, I first trundle behind our photo car, alternately backing off and accelerating. Even at those low speeds, the engine feels like a volcano about to pop. Squeezing the throttle results in a brief moment of turbo whistle and then BOOM!, the car gallops forward. It’s impossible to maintain a slow speed. This thing is either on or off, the byproduct of a small engine breathing into a big turbo – until that huge fan gets turning, it’s like you’re dragging the ship’s anchor, a reason Audi’s drivers in the period didn’t lift if they could possibly avoid it.

When Audi’s four-wheel-drive advantage evaporated with the arrival of competitors, the company hacksawed a foot from the wheelbase in 1984. The long, luxurious Quattro evolved into the stubby Sport Quattro, and the car here is the heavily modified racing version.

The surgery only partially alleviated the Quattro’s porky nose; designed with production cars in mind, the Quattro’s peculiar powertrain layout places the engine, mounted longitudinally – bumper to windscreen – ahead of the front axle to make room for the transmission and front half-shafts, which concentrates the weight up front. Most of the other new Group B cars, excluding the exceptionally weird and uncompetitive Citroën BX 4TC, positioned the engine just in front of the rear axle. Shrinking the wheelbase, the distance between the two axles, shifted the weight rearward, and for the racing car, Audi also crammed the radiators into the boot.

The carbon and Kevlar composite bodywork shows how far competition versions were changed even from their low-production street versions. The fenders flare a comically wide 11 inches from the bodyside, and huge front and rear wings produced downforce to further aid traction.

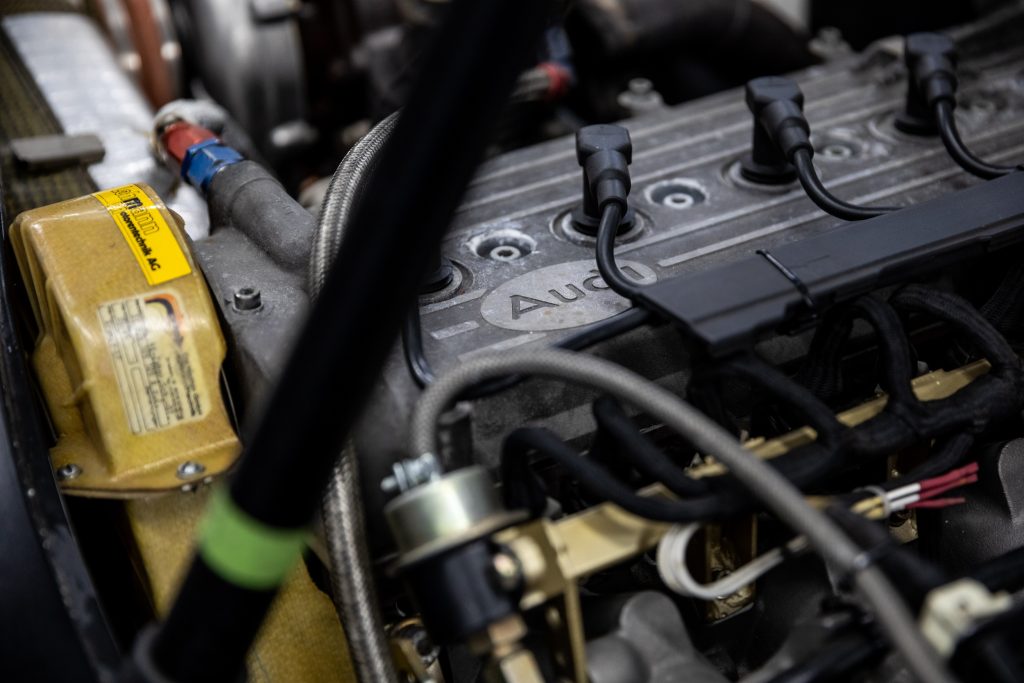

Even with four-wheel drive, the turbocharged engine can easily spin the tyres on loose surfaces. Fitted with four valves per cylinder and a massive KKK turbocharger, the 2.1-litre mill produced roughly 500 horsepower in the day. That figure, however, was adjustable thanks to an underhood knob that alters the turbo boost pressure, producing at times whooshes and exhaust bangs that echoed through the 1980s forests.

This particular car had an unusually easy life for a rally car, running only one event in 1985 with 1984 WRC champ Hannu Mikkola behind the wheel. It then briefly served as a practice car until moving into private hands, where it was occasionally street-driven. One of the compelling advantages of a rally car over other vintage racers is that they were originally made street-legal because they were driven on public roads between the race stages. The current owner purchased it last autumn in England for $2.3 million and brought it stateside. The odometer reads 20,000 kilometers, which means this one averaged 300 miles a year.

The odo resides in a busy, utilitarian dash. Fuses and relays live in the middle for easy repair. They’re labeled in German. A bevy of unmarked gauges present engine functions to the driver. The passenger, or co-driver, whose job was to call out the severity of upcoming turns plus several other tasks, monitored a bank of radios, precise distance computers, and the fuel level. The cars were often miles from their service areas, so there’s a handheld mic to communicate with the crew. Coolant lines travel through the passenger footwell.

The five-speed transmission runs through a conventional H pattern, and there’s a button on the shift knob that automatically operates the clutch. Pressing the button engages a system that pushes the clutch to the floor. Releasing the button lets the clutch out. This system allowed drivers to change gears while left-foot braking, a widely used rally technique employed to drift the car sideways and also reduce turbo lag by lifting completely off the throttle as little as possible.

The car rides tall on its spongy springs and it feels like it’s on ball bearings ready to pivot in either direction, yet it’s somehow planted, too. There’s a toughness to the machine that’s more tractor-like than racing skiff, a feeling that it can take a beating over dirt, rocks, jumps, or whatever else the woods of Europe or the grasslands of Kenya had to offer.

After a few laps, the shooter pulls off, and I do what any sane human would do: I stand on it. There’s that turbo-fueled explosion and then, oh no, it sputters. The assembled crew empties debris from the fuel filter, but the problem never goes away. Later, we learned that gunk from the aged tank had fouled the fuel pump. Damn.

No car likes to sit. Let’s hope the new owner keeps the cobwebs off and invites us back.

Specs: 1985 Audi Sport Quattro S1 E2

• Engine: 2.1-litre DOHC I-5

• Horsepower: 500 bhp @ 8000 rpm

• Torque: 435 lb-ft @ 5500 rpm

• Weight: 1,088 kg

• Power-to-weight: 460 bhp/tonne

• 0-60 mph: 3.0 sec

1984 Peugeot 205 T16

From the driver’s seat, only the large red “Turbo 16” lettering on the steering wheel gives a clue that this is no ordinary 205. The short, downward-sloping hood and thin pillars provide vast visibility. The seats rest on a shelf, which covers the fuel tank, and the relationship between the seats, the steering wheel, and the shifter all feel perfectly natural.

The first sign that you’re in a different sort of car is the stiff clutch pedal. The manual steering is firm, too. Firing the engine brings a mechanical clatter to the cabin and loping idle. Once underway, the whole car feels a bit leaden and surprisingly not that quick. Unlike in the Audi, there’s no huge hit from the turbo, but rather a gradual buildup that doesn’t really get going until the tachometer is 2,000 rpm short of the 7,500 redline. In that range, the engine musically howls like an F1 car.

Peugeot was on its heels before the compact 205 model that debuted in 1983. Shoved by the French government into a shotgun marriage with bankrupt Citroën in 1976, Peugeot was losing almost a million dollars a day by 1981. It needed a slam dunk in a high-volume segment like the economy hatchback.

Back then, Peugeot sold only the 504 and 604 sedans stateside; we never got the cut-price 205 because the company feared a bottom-feeder slugfest with Japanese and VW imports. That was probably a mistake, as the European press widely lauded the smartly styled 205 – especially the GTI version of 1984, which would have been a credible alternative to the VW Rabbit/Golf GTI. Perhaps if Peugeot had found the money to federalise the 205 in the U.S., the company wouldn’t have left our shores in 1991.

In 1981, Peugeot hired former rally co-driver Jean Todt to start a new racing division, Peugeot Talbot Sport. Todt – who later engineered Ferrari’s last F1 glory days with Michael Schumacher and Ross Brawn, then went on to run the FIA – commissioned a 200-unit run of 205s to homologate the car for Group B rallying.

Renamed the T16, the car cost about the same as a Porsche 911. The economy car-turned-racer was expensive because the T16 shared almost nothing with the standard 205. Starting with a two-door 205 body shell, fabricators cut the car in two behind the front seats, threw out the back half, and welded in a steel powertrain and suspension sub-frame. The four-cylinder motor, which used the block from a diesel engine and a 16-valve cylinder head, sat crossways behind the passenger seat. The transmission, from a Citroën XM, was behind the driver and routed power to both the front and rear axles. A large clamshell that hinged at the front provided generous access to the rear. The suspension was thoroughly reworked and widened, which required fender bulges at every corner.

Racing versions of the T16 had upward of 500 horsepower, but there’s only 200 in this street version. A heady figure in 1984, it feels sedate today and not enough to reliably drift the car on asphalt. Perhaps, however, all 200 weren’t present on our day. All the action in this car is where the weight is concentrated, out back. In contrast, the front end feels light and underloaded. If that sounds unbalanced, the combination works, and the T16 is an extremely predictable and correctable handler.

That well-sorted suspension is the shining light in a car that has a bit of a homebuilt feel. There’s an overall coarseness to the machine, a reminder that it was polished just enough to sell the required 200 units and that’s it. The car’s role was, after all, to go racing. You have to wonder, though, how good it could have been with more development.

It could also be said that the T16 oozes character, the rough edges a reminder of a time when a set of rules gave us a mid-engined economy car that we wouldn’t have otherwise had. With that lens, the T16 is a gem.

Specs: 1984 Peugeot 205 T16

• Engine: 1.8-litre DOHC I-4

• Horsepower: 197 bhp @ 6750 rpm

• Torque: 188 lb-ft @ 4000 rpm

• Weight: 1,211 kg

• Power-to-weight: 163 bhp/tonne

• 0-60 mph: 5.7 sec

1994 Lancia Delta Integrale EVO II

A suede-covered throne with large side supports cradles the driver of the Lancia. You wear this pissed-off little box as much as sit in it. The wide and unobstructed view, thanks to the low beltline and thin pillars, is a refreshing departure from today’s cocoon-like safety cockpits. The gauge cluster features a graph-paper motif, so ’80s. The only weirdness is the position of the nonadjustable steering wheel; it’s low and far away, a setup made for the short-legged. That minor discomfort disappears when slinging the Evo through corners. The front tyres faithfully bite when turned and the rears drift just enough to assist the rotation. Flicking the car through a series of left and right bends comes easily, like the chassis is eager for the workout.

Lancia’s World Rally Championship success started with the Stratos, a squat limpet of a car with a Ferrari V6 that was arguably the first car built specially for the WRC. The Stratos won the laurels in 1974 and followed that up with two consecutive winning seasons. So it was no surprise when Lancia’s longtime motorsports chief, Cesare Fiorio, leaped into Group B – first with the rear-drive 037, loosely based on the production mid-engine Lancia Montecarlo, and next with a four-wheel-drive version of the Delta family hatchback.

Introduced in 1979 wearing a crisp, Giugiaro-designed body, the Delta was positioned as a premium small car. The tube-frame, Kevlar-bodied Group B Delta S4 version first raced in late 1985, and when driver Henri Toivonen trounced the field at the first event of 1986, Lancia became the front-runner. A few races later, however, Toivonen was dead. The Lancia team, which likely lost a spiritual edge after the accident, soldiered on to finish runner-up behind Peugeot for the championship.

The tragedies obviously overshadowed the S4, which was probably the best of Group B. As with the T16, the S4 carried its 1.8-litre engine behind the seats. The car’s main trick was a novel induction system that combined a crank-driven supercharger for low engine speeds and an exhaust-driven turbocharger for boost on top, thus flattening the power delivery with the goal of making this rally monster easier to drive. The car made some 500 horsepower and weighed only around a tonne.

For 1987, Group B was replaced by the more production-based Group A. Under these new rules, eligible cars needed to have four seats and a manufacturer had to produce a whopping 5,000 examples within a year. There were few allowed modifications, so rally cars once again hewed close to what people could buy. This cost-saving change suited Lancia, as well as Subaru, Mitsubishi, and other newcomers that were future stars on the circuit.

However, Lancia already had an ace, the Delta HF 4WD with a 2.0-litre turbocharged engine. The HF won nine of 13 races in 1987 and the championship. With the Delta, Lancia won the manufacturers’ championship every year until the factory pulled out after the 1992 season, an incredible run. Over that period, the Delta was continually massaged with improvements like fender flares that accommodated larger wheels and tyres and a 16-valve cylinder head for more power. The last of the line, the car with every lesson learned, is the car pictured here, the Delta Integrale Evo II.

The Evo is a flared, shaved, and squared-off hot rod. Giugiaro’s clean lines gave way to a bonnet bump to clear the 16-valve head, and those lovely fender flares, which weren’t fibreglass but stamped sheet steel. The long list of exterior accessories added to the Evo over the standard Delta, which included a small rear spoiler and round headlights to replace the production Delta’s rectangular ones, reads like Lancia went a little nuts with a JC Whitney catalog. Yet those bits combine to make the Evo look aggressive yet distinguished and smaller in person than it does in photos. The Integrale is just under 13 feet long and within a few inches of a first-gen Mazda Miata.

Within that svelte dimension, Lancia fit four-wheel drive, a 215-hp turbo engine with intercooler, rear seats, air conditioning, and a reasonable luggage compartment under the rear hatch. Kudos for the packaging genius, but God help whoever has to fix one.

Above 3,000 rpm, the engine remains wide awake. Unlike many turbo cars of the era, there are no lurches or peaks in the power delivery. It doles out thrust in a long frenetic rush to the redline. The smoothness is no doubt aided by the dampening effect of four-wheel drive, which means there’s plenty of rubber to turn horsepower into acceleration and not wheelspin. The engine also has balance shafts, which smooth the vibrations that are common with four-cylinder engines.

There’s harmony to the car, a just-right and consistent effort for all the inputs, that remove distractions so the pilot can simply enjoy driving. By 1994, the Delta platform was 14 years old and the constant refinement brought forth a frisky, taut, and supremely entertaining street car. Only reluctantly did I hand back the keys.

The Integrale is considered the cream of the hot hatchbacks and there’s truth there, with a footnote: When new, the Evo cost about 30 grand, or double the contemporary VW GTI. Today, the Hagerty Valuation Tool puts the value for good-condition Evos over $100,000, even though like Skyline GT-Rs, they’re not particularly rare. Some 2500 Evo IIs were made between 1993 and 1994. They’re probably not going to get cheaper.

Specs: 1994 Lancia Delta Integrale EVO II

• Engine: 2.0-litre DOHC I-4

• Horsepower: 215b hp @ 5750 rpm

• Torque: 232 lb-ft @ 2500 rpm

• Weight: 1340 kg

• Power-to-weight: 160.4 bhp/tonne

• 0-60 mph: 5.7 sec