Rally fans, rejoice: The film Race for Glory: Audi vs. Lancia, set in the thick of the infamous Group B era of the World Rally Championship (WRC), is out now in theatres and streaming. It focuses on an exciting 1983 season that saw two teams separated by wide gulfs in technology and budget, but also by a mere two points at the end of the fight. It will be exciting to see the drama play out on screens big and small, but the story of Audi and Lancia in Group B goes a lot deeper than a movie script.

Since a spotlight is shining on this dramatic (and under-the-radar, relative to the excitement it offered) period in motorsports, now is the perfect time to dive into the history of the series, the cars, and the blossoming market for them now that they have become highly collectable classics.

The “Killer Bs”

The Group B era of the WRC came and went quickly, only lasting from 1982 to 1986. Those five short years, however, are still the most talked-about period in the history of the sport. From Group B’s dawn to its demise after one too many fatalities, the horsepower of top-level rally cars doubled, while rallying saw unprecedented advancements in everything from aerodynamics and drivetrain technology to team management.

Factory-backed teams dumped Formula 1–level money and technical expertise into developing their cars. F1-level cash and tech bought F1-level speeds, thanks to forced induction, light weight, and four-wheel drive. What had been a sport for mostly recognisable, production-based cars now saw some of the most sophisticated and quickest cars on the planet, all on twisty, narrow, multi-surface rally stages that were considerably longer and more exhausting than those in today’s World Rally Championship. As power figures and aerodynamics became more advanced, Group B cars became so fast and their rides so jarring that some drivers suffered from tunnel vision and needed spinal decompression between stages.

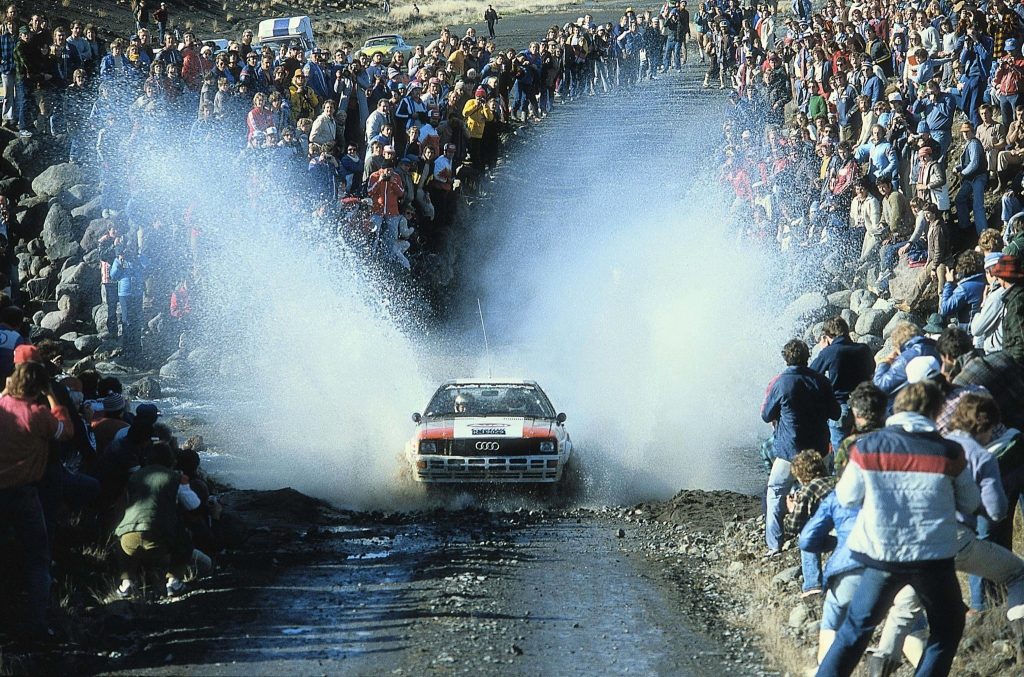

The sport only got more popular as the cars got more dangerous. Organisers did little about it, so crowd control issues plagued Group B, with many stages at crowded rallies like Argentina and Portugal bordered not by guardrails or tyre walls but by human beings. Nothing stopped spectators from stepping into the road in the middle of a run, and some fans even tried to touch cars as they sped, or even flew, by. The Peugeot and Lancia teams reportedly found hair and blood and even severed fingers in the ducts of their cars between stages, although no fans are known to have tried to reclaim a lost digit.

The savage speed of the Group B cars and the enormous, unfettered crowds that flocked to see the “Killer Bs,” as they came to be known, was unsustainable. The nickname wasn’t just cute wordplay, either – people died. The Lancia of driver Attilio Bettega took his life at the 1985 Tour de Corse (Corsica). At his home rally in Portugal in 1986, Joaquim Moutinho da Silva Santos crashed his Ford into a crowd of people, killing three. There were plenty more minor incidents besides, but the death of star driver Henri Toivonen and his co-driver in another Lancia at Corsica in 1986 was the last straw. For 1987, the sport’s governing body ended Group B and reverted regulations for top-level rallying to the much more pedestrian Group A ones, bringing the most notorious period in the WRC’s history to a close.

How Group B started, and where it’s headed

Group B arose from the FIA’s shuffling of the regulations in 1982. Once it became the top-level racing class, organisers intentionally left the rules vague and open to interpretation in order to lure large carmakers into the classification. What rules there were stipulated this: a fixed roof, two seats side by side, and a minimum weight determined by engine displacement, with forced induction displacement calculated at a multiplier of 1.4x. Finally, manufacturers had to build 200 examples in a 12-month period to homologate the car for Group B, half as many as were required in the Group 4 class that came before it.

The most successful Group B cars were designed first and foremost to win rallies. The carmakers therefore only built road versions because they had to. The road cars were complex, sparsely trimmed, and extremely expensive, especially for what looked like little more than a souped-up Euro hatchback. But they were fast, and remain so even by modern standards. In addition to the raw driving experience they offer, they’re incredibly rare and have a historical connection to one of motorsports’ most exciting chapters. Those are all ingredients of a collector car, but only within the last decade have Group B homologation cars garnered serious appreciation.

It’s no secret that sporty, boxy cars from the 1980s came back into fashion during the late 2010s and early 2020s, and it doesn’t get much sportier (or boxier) than Group B. While the homologation cars were a hard sell when new and their values remained sleepy for years, they now show up at auction or in the showrooms of high-end dealers regularly. Once confined mostly to European markets, they are also reaching American shores, where the cars were never officially sold and where most people only know Group B from watching the cars slide, skid, and narrowly miss spectators on YouTube. Or, in 2024, from when they star on the big screen.

As the historical significance and technical sophistication of these cars gained recognition, their prices got higher, too, with good examples selling deep into six figures. Exceptional cars, especially race cars with wins to their record, have brought over seven.

Another big appeal, despite the exotic nature of Group B cars, is their usability. For Max Girardo, whose dealership Girardo & Co. has showrooms in Oxford and Turin, “collectors are finally realising these cars are usable, and enjoyable, with many having played an important role in motorsport history. They’re welcome at concours events or, even better, thanks to their road titles you can take them to [a] cars and coffee (and you’ll be the only one with a rally car).” As for the significance, he says, “some of the younger generation are now at a point where they can afford to buy a car they watched as a youngster on a World Rally stage being driven by their hero.”

Concours events, vintage rallies, local shows, and casual weekend drives aren’t usually all possible in one classic. “You can’t do that with an F1 car, can you?” adds Girardo, who regularly buys and sells Group B rally and road cars. “Maintenance is not particularly difficult, but they do benefit from some specialist attention as they all have their own quirks,” he says.

Several carmakers, not just Audi and Lancia, had a go at Group B and their efforts are all increasingly collectable. They include the Ford RS200, which came out too late to be properly developed; the Renault R5 Turbo, an old design merely adapted to Group B specs; and the Austin Metro 6R4, whose creators made the bold but unsuccessful choice of installing a naturally aspirated engine with a larger displacement rather than use forced induction like its competitors. Even the Citroën BTX 4 TC, which was so bad the company tried to buy back and destroy the road cars, is starting to show up at high-end auctions. The Peugeot 205 T16, meanwhile, took full advantage of Group B’s regulations (or lack thereof) and was technically the era’s most successful car with 16 overall victories and two World Championships to its credit. In particular, though, the Audis and Lancias emotionally capture what Group B was all about, and price-wise are the high points in Group B collecting.

The Audis

Audi, having introduced all-wheel drive to rallying and smoothed out its early problems (weight, complexity, reliability), was poised to dominate the early days of Group B. Having raced the Quattro in 1980 and 1981, Audi had already developed the car well. When Group B regulations were announced, the car was further modified to meet them. The Germans won the manufacturers’ championship in the first season of Group B, marking the first title for a 4WD car. The improved A1 and A2 versions of the Quattro took the fight to Lancia in the 1983 season, and Audi continued to improve the car right until the team pulled out in 1986.

After just missing the title to the Italian underdogs in 1983, Audi came back with a vengeance in 1984. The production-car roots of the Quattro always left it with an Achilles heel: The engine sat too far forward in the chassis and compromised handling – a bit of a problem, given how twisty a rally can be. It was nevertheless always competitive thanks to the massive power from the 2.1-litre five-cylinder turbo, consistent improvements in four-wheel drive, and big budgets. Sheer talent from an incredible driver lineup didn’t hurt, either. Audi’s aces included Walter Röhrl, Stig Blomqvist, and Michèle Mouton, the 1982 runner-up and closest we’ve ever come to a female world motorsports champion.

The Sport Quattro, Audi’s new entry homologated for 1984, was the company’s first proper Group B design. Compared to the Ur- (German for “original”) Quattro, the Sport Quattro was over a foot shorter, featured carbon-Kevlar body panels, and had wider wheels as well as brakes derived from the Porsche 917. In the WRC, the flames thrown out of the exhaust pipe, the chirps and whooshes of the massive turbo, and the massive shovel of a front air dam on the later S1 E2 versions also made the Sport Quattro the poster child of the Group B era, and Audi’s dominance in the 1984 World Rally Championship foreshadowed its steamrolling at Le Mans 20 years later.

Audi built a total of 214 Sport Quattros for Group B homologation, and a little over 160 of those were sold to European customers for an eye-popping 200,000 DM – the equivalent of nearly £50,000, and comfortably more expensive than a Porsche 930 and even some Ferraris. Then again, the Audi was quicker.

In road trim, the Sport Quattro put out a reported 306 horsepower and 258 lb-ft of torque, came with fully adjustable all-wheel drive and anti-lock brakes from the rally version, and could scoot to 60 mph in 4.8 seconds. Another nice thing about the Sport Quattro, according to Girardo, is that “the build quality is the best out of all the Group B road cars and it is the most compliant on the road, so it is the most usable.”

Once they hit the secondhand market, Audi’s old rally cars and the road-going Sport Quattros didn’t come up for sale much until recent years. The results, while never cheap, were still quite modest compared to today. An ex-works rally car sold for £100,000 at an H&H auction in 2003, then one sold for €103,500 (about £82,000 at the time) in Monaco in 2008. Even Stig Blomqvist’s 1982 Quattro Rally car sold for just £58,700 in London in 2004. And as recently as 2013, a 39,000km Sport Quattro sold for £115,740.

Then, RM Sotheby’s sold a two-owner, 8300km Sport Quattro in January 2015 for £263,000. That sale set the benchmark for Group B–era machinery, and Sport Quattros have come to market more often and brought a lot more money since. One sold a couple of months later, in March, for £287,100. One brought £403,200 in 2016, and another one sold for £375,000 at Quail Lodge in 2017. In 2019, another Sport Quattro sold for £328,000 in Amelia Island. In 2022, a 1985 ex-works car sold for £1,805,000, but the current record for Group B machinery is a Sport Quattro rally car that actually never raced in anger in period but had one private owner since new. It sold in 2021 at Artcurial Paris for €1,968,000 (£1.73M), about double its pre-auction low estimate.

The Sport Quattro is also the only Group B homologation special currently in the Hagerty Price Guide, with #2 (Excellent) values currently at £331,000.

The Lancias

Compared to Audi, Lancia and Abarth (the latter of which did most of the design work) didn’t have much cash to throw around. As a result, their first Group B car, the Rallye 037, wasn’t the technical tour de force that its German rival was. Rear-wheel-drive and supercharged instead of turbocharged, it was by far the more conventional of the two, but it certainly was quick.

The 037 was lightweight and sported a punchy, mid-longitudinally mounted engine based on the unit used in earlier Fiat Abarth 131 rally cars. On mud- or snow-filled rally stages it couldn’t keep up with the Audi, but the 037 cleaned up on tarmac and gravel. Though it was unreliable in its 1982 debut season, it improved tremendously and triumphed in ’83. After that storybook win, however, Audi’s improved ’84 car was simply too much, and the 037, while competitive, was outclassed. The final shining moment of rear-wheel drive in rallying had passed.

Of all the outrageous, fire-spitting cars to come out of the Group B era, though, the Delta S4 might be the most extreme and the most clever, even if it never took home a championship. Even after taking the 1983 title with the 037, Lancia had to admit four-wheel drive was the way of the future. Going back to the drawing board as the 037 dropped down the time sheets behind Audis and Peugeots, Lancia designed the Delta S4 around the Group B regulations rather than adapting it from an existing road car. It may have been called a Delta, but the S4 has almost nothing in common with Lancia’s small family hatchback.

Underneath detachable two-piece composite bodywork, the S4 was built on a tubular spaceframe chassis with double wishbone suspension at both ends and a state-of-the-art three-differential, rear-biased four-wheel-drive system. To combat the lag endemic to many 1980s turbos, Lancia got even more clever and employed the first-ever twincharging system, fitting both a Volumex supercharger and a KKK turbocharger to the S4’s mid-mounted, oversquare, and Abarth-developed 1.8-litre four. The idea was to widen the power curve with the supercharger, giving boost at lower rpm for blasting out of slow corners, while the turbocharger provided maximum power at the top of the rev range.

The car was a winner right out of the box, scoring a 1-2 finish at the 1985 RAC Rally, its debut event. About 500 horsepower was the norm back then, though cranking up the boost provided even more. Legend has it that during testing for the Rallye de Portugal, an S4 lapped the Estoril Formula 1 circuit fast enough to qualify in the top 10 for that year’s Grand Prix.

The Delta S4 is also the car that effectively killed the series. Henri Toivonen, a gifted 29-year-old Finn who many commentators regarded as the only driver capable of taming the S4, was leading the 1986 Tour de Corse rally by a large margin before he went off course and plunged into a ravine on the event’s 19th stage. The fuel tank, unprotected by a skid plate and placed under the seats, burst into flames, and both Toivonen and his co-driver, Sergio Cresto, were killed. It was the Lancia team’s second fatality in Corsica in as many years. Within hours, Group B was effectively banned for the following season. Ford and Audi withdrew from the class immediately, and in 1987 many Group B machines were relegated to rallycross racing.

Like many Group B road cars, the 037 and the Delta S4 were hard to offload when new – the S4 particularly so. The twincharged powertrain with 250 hp in road trim was not enough to offset its 100M-lire price tag and goofy looks. Some Delta S4 Stradales supposedly remained unloved and unsold at dealerships well into the 1990s, which is even more surprising given that Lancia likely didn’t even build the required 200 examples to qualify the S4 for Group B. Number fudging for homologation is not at all unheard of in racing, especially among the Italians, and Lancia may have built as few as 70 S4s.

Like the Sport Quattro, the Lancia 037 had a breakout year in 2015, when a Stradale version sold for €336,000 (£264,580). Then, in 2017, another one sold for a more modest £205,000, but prices went up again when one sold for £327,000 in 2018. More recently, sales have crossed the half-million mark, with Stradales selling for €770,000 (£685,000) in 2019 and €451,000 (£386,500) in 2020. An original rally car fetched €548,320 (£488,000) in 2021, and two Stradales also crossed the block, one selling for an even £414K in 2022 and the other for £515,000 in 2023. The biggest result for a 037 is the works rally car driven by both Markku Alén and Walter Röhrl that sold for £1,045,625 in 2022.

As for the more extreme Delta S4s, Christie’s sold one nearly 20 years ago for the princely sum of £34,075 . How times have changed. A 2200km, like-new Stradale (street version) sold for €1,040,000 (£955K) at the 2019 RM Sotheby’s Essen sale, well over its €500,000 estimate. That made it the most expensive Group B car ever sold at the time, and the first to break seven figures. With few exceptions, the going rate for an S4 in recent years has been a bit ahead of the Audi Sport Quattro, with one selling at Pebble Beach in 2016 for £341,000, one at Quail Lodge in 2017 for £341,000, and one at Quail Lodge in 2018 for £333,000. The S4 that won the model’s debut rally in 1985 sold for £764,375 in 2019, while other ex-works cars sold for €770,000 (£676K) in 2020, €810,560 (£716K) in 2021, and £1,636,250 in 2022.

Led once again by Lancia and Audi, Group B has recaptured the passion of car enthusiasts. Will the silver screen help further mythologise this era and boost values? We’ve got our popcorn ready to see where these rally monsters go next.