It’s easy to say the Jaguar XJR-15 was a car ahead of its time. It’s not so easy to illustrate why. To try, imagine wandering into your local WHSmith on 8 April, 1991, searching for the latest edition of Autocar. There were two major reports that the magazine’s front cover shouted about on the newsstands, that week. The first was a drive of the XJR-15, the other a drive of the ‘new’ Mini Cooper S – yes, the same, Issigonis peoples’ car that had been with us since 1959.

The juxtaposition of the two British cars was clear. The Mini was a last-gasp attempt to extract a few more sales out of a design that had outlived its relevance to most drivers. The Jaguar, a barely disguised racing car, brought motorsport innovation to the road and promised impossibly wild performance for the dreamers – not to mention the fortunate few who could afford it.

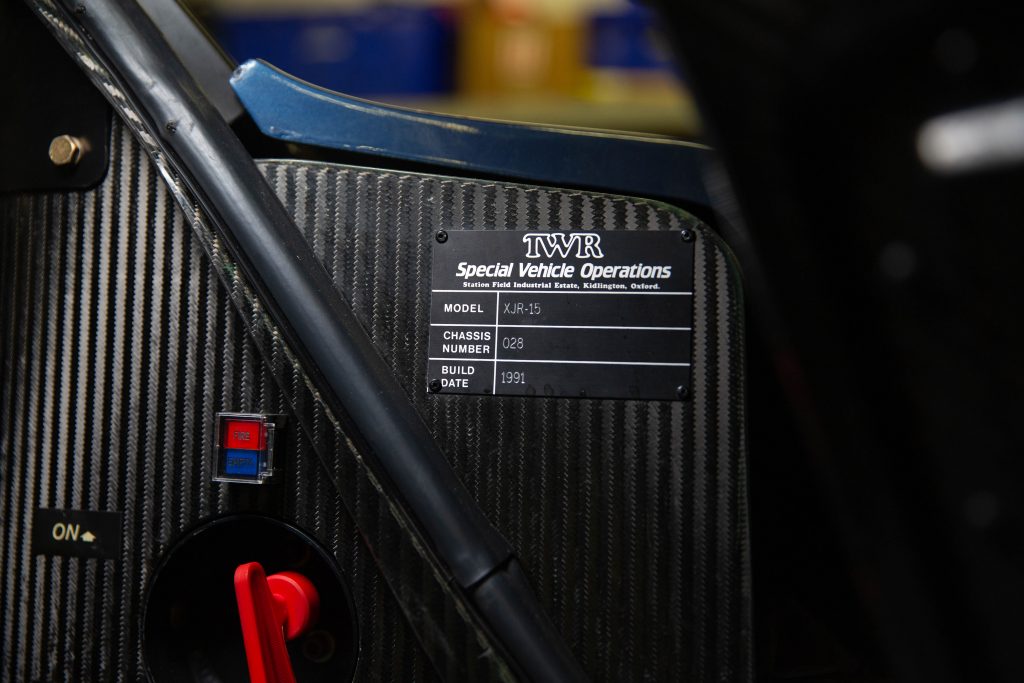

Jaguar had beaten Aston Martin, Bugatti, Ferrari, Mercedes and Porsche to the title of creating the first road-legal car to be built around a carbonfibre monocoque, and the price tag was suitably exotic – £450,000. But it wasn’t the executives at Jaguar who were deserving of praise; none of it would have happened without the cunning and determination of Tom Walkinshaw, the driving force behind Tom Walkinshaw Racing.

At the 78th Goodwood Members’ Meeting, in amongst a field of XJR-15s that were being run to mark the 30th anniversary of the British supercar that slipped below the radar in so many ways, Peter Stevens, the designer of the XJR-15, takes up the story of Britain’s lesser-known supercar.

“It’s a delight to see them because they actually became a very well-kept secret for a while, in effect,” says Stevens, alluding to the fact that Tom Walkinshaw and Jaguar had been developing supercars of their own in isolation – Walkinshaw the XJR-15, Jaguar its XJ220.

For several years, Walkinshaw had been toying with the idea of a road car based on the very same, V12-powered machines that would compete at the Le Mans 24 hour race. At its simplest, the idea was a nostalgic attempt to recapture the time when it was possible to buy a C-type and D-type (or indeed the XKSS) much like the ones beating the competition on the race tracks of Europe.

“Tom had been thinking of doing a road car and he did a jacked up version of the XJR-8 [the 1987 Group C racing car that pushed aside Porsche’s ageing 962] and it looked awful,” chuckles Stevens. “I was working as a consultant, and then Tom called me up and said, ‘Do you want to come up to the Birmingham Motor Show? There’s something I think we should have a look at.’ And we went and saw the XJ220 there – the 220 then wasn’t real, it was an idea of what a Jaguar supercar could be.

“And Tom said, ‘I think we could do something more exciting than this. This is like a posh touring car – I think we could do something more exciting.’ And he said, ‘When could you have some drawings for me?’” With an idea of the direction in his head, Stevens would be back within a fortnight with some initial renders.

“It was very apparent immediately that you couldn’t make a road car out of that racing chassis, because there wasn’t enough room inside, not enough headroom, you know, and the kind of people who would buy it weren’t racing drivers, who are nimble, and the racing driver wants to be in a car and if it’s difficult to get in it doesn’t bother him because he wants to be in there. Whereas the customer has to try one of these and not embarrass himself getting in.

“So we were given the tub which Win Percy had gone end over end at [the 1997] Le Mans,” recalls Stevens. The carbonfibre monocoque was key to giving Jaguar a competitive advantage over Porsche, due to its immense strength. Indeed, when interviewing Tony Southgate, the engineer responsible for designing Jaguar’s successful sports racing cars, he told me how Walkinshaw would often berate his drivers for forgetting to unplug their helmet’s intercom lead, which would often break the car’s pit-to-car communication equipment when they extracted themselves from the car. After Percy made it back to the pits, following a tyre failure at over 200mph on the Mulsanne straight and an almighty accident in the small hours of the morning, he told Walkinshaw: “The good news is I remembered to unplug the intercom system before I climbed out of the wreckage!”

“We sawed off half of the Win Percy car,” said Stevens, “so we could show Tom the differences and did the new shape, just as a kind of seating buck, so Tom could see if he could get into it. It started like that, just with a very small group of us.”

At the time, Stevens was working with Lotus and had finished the new Elan, the front-wheel drive M100, and knew that with General Motors in the background looking to offload Lotus there wouldn’t be another new car for a long time. The chance to craft TWR’s secret supercar was too great to resist.

Walkinshaw had set a timeline, immediately after Jaguar’s fourth place at the 1989 Le Mans race: “From the start of liking the drawings and choosing something, Tom said, ‘I want to drive one [a finished XJR-15] when I come back from Le Mans next year’” remembers Stevens.

All this on a shoestring while flying under the radar without Jaguar’s knowledge – explaining the need to design the new supercar in the unlikely environment of a car park.

“The model-making people who were over near Coventry, they would come across on a Wednesday evening and at the weekend with a van, with the modelling table and the scale model in the back, and we’d work on it in the car park at Lotus on Wednesdays and in the car park in Bungay [Norfolk] where I was living at weekends, and then I would go across [to Coventry] every other week to look after the full size model.”

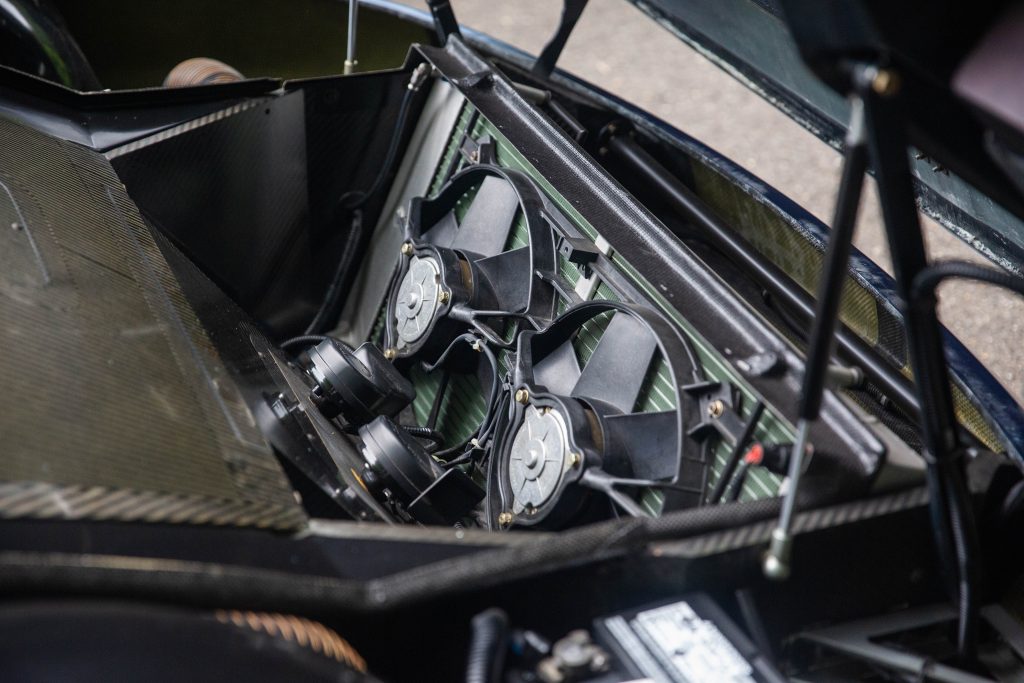

The carbonfibre core of the car was new for the XJR-15 with its unique dimensions but created to the same specification of materials and the techniques the XJR-9 employed. “It was fairly straightforward, because we used basically the same suspension,” remembers Stevens. Despite the project “costing peanuts” Walkinshaw cut a deal with Bridgestone for the cars’ tyres, but this meant the tyres ended up being taller than needed, which led to the car having more ground clearance than desirable, reducing its downforce and increasing its propensity to roll into oversteer.

At the time, Stevens and the team gave a lot of thought to the typical customer of a £450,000 Jaguar supercar. And they decided against relying on downforce too greatly. “It would be bought by wealthy people who might not be that experienced, and part of our job is to look after them – and make a car which is aerodynamic, safe and stable. There isn’t a lot of downforce, because you don’t actually want that on a car you’re going to be using as a road car

“And then for ‘91 there was the race series because when he [Walkinshaw] had to own up to Jaguar, his right hand man Andy Morrison had said ‘Well why don’t we do it as a race series? We’ve got 16 spare race car gearboxes, so that’s how many race cars they’ll be.’ Which is why there’s a different gearbox in road car and race car.”

Ah yes, the race series. The 6-litre, V12 machines with 450bhp could be entered for the Jaguar Intercontinental Challenge, which was a three-round series with star drivers from F1, sports cars and touring cars. In 1991, it would visit Monaco, in May, Silverstone in July (piggybacking onto the British Grand Prix) where each winner would drive away in a new JaguarSport XJR-S coupé. For the grand finale, at Spa in August, things got decidedly more interesting: a jackpot of $1m was up for grabs.

How does he feel the design has aged?

“I thought you shouldn’t do something just of the moment. And it was the same with either Lotuses or the McLaren [F1]. A GT40 now just looks like an old car, in the way these don’t really look like an old car because they don’t rely on little styling gimmicks of the time, the same as it is for an F50 [Ferrari]. So to that extent, almost because of my conservatism – but not conservative because I’m conservative, but because I knew we were only going to do one road car, with Tom, and it had to last in terms of a valid look.”

Stevens’ preference for an unfussy, unadorned aesthetic wasn’t the only thing he took with him when he wrapped up with TWR and went to work with Gordon Murray, on the McLaren F1. There was huge significance in what he’d learned about using carbonfibre for a road car.

“I actually I took Gordon Murray up to TWR to look at the way we were doing it. And I told him if we try and do something too complicated, particularly at the time with carbon, it either will be made of multiple pieces, which had to be so carefully put together, or it doesn’t work because I described carbon as being about as handy as boilerplate in terms of moulding it, because the whole point of carbon is the fibres are so stiff, that you can’t persuade it to go where it doesn’t want to go.

“It was probably one of the best fun projects because we were just a tiny group, as we were with McLaren; we didn’t have any kind of ego at TWR at all, which was really nice, actually. Tom was just good fun – good fun all the time. He got hopelessly steered by people later in his career, but I was very fond of him.”

Driving the Jaguar XJR-15 gave David Brabham a break with TWR

“It was a bolt out of the blue for me. I didn’t know about the championship; I was racing in Formula 3000 at the time [with Ralt].

“The car wasn’t designed to go racing. It was designed to be a road car and sell, and then later it went racing. When we first started driving it it was a real handful, but after you got used to it you learned to adapt and drive around it and go as quickly as possible.

“We went to Monaco and I finished second, behind Derek Warwick. It was during the qualifying that I decided that I should crack on. Up to that point it had been so ‘taily’, so through the tunnel it was oversteering. When I looked at the pit board I saw I was one and a half seconds off the pace, and I thought, ‘Bugger that, just get your foot down!’ and it was just a case of toughing it out. I qualified fourth, I think, finished second, and then got asked to race the XJR-14 WEC program, based off that result.

“After the race, they [TWR] said, how would you like to come and test the XJR-14? I had to speak with my F3000 team, because I was already committed there, and they told me they were about to run out of money, and said ‘Crack on!’ so the series helped launch me into sports cars. It was a great moment.”

Read more

“I want to find out for myself” – I was there the day Ayrton Senna went rallying

The likely lads in a lock-up who made it to the F1 grid

How the BMW M1 Procar championship was dreamed up over beer and whisky

Great read – thanks!

Any chance of a piece on the XJR-14 mentioned in the article? Stunning car, that.

What a great inside story with Peter Stevens,who knows all that stuff like it happened yesterday!

Very knowledgable person ,the creator of the timeless beautiful design XJR 15.

Glad you enjoyed it, Michael. Peter is always so generous with his time and stories. And the XJR-15 is a rare and thrilling creation – as you well know!

Having help build the Le Mans cars it is interesting to see what else was going on like the Ilmor pushrod motor for Indy which Paul never let on until I was at Indy that year