With its distinctive six-wheel configuration, the Tyrrell P34 is one of the most famous Formula 1 racing cars ever built. Yet it is also one of the rarest, after cars with more than four wheels were banned by F1’s rule makers. So when one wealthy racing driver was unable to buy an original P34 for historic motor racing, in the summer of 2018, he did the next best thing and commissioned the construction of a replica six-wheeled Tyrrell.

Jonathan Holtzman, a “crazy-keen” American driver who competes in the Masters Historic Racing Formula One championship, turned to CGA Race Engineering, based in Warrington, and posed the question: what would it take to build a continuation of the 1976 P34 (chassis no. 9)?

The P34 was Formula 1’s short-lived six-wheeled oddball, winning the hearts of racing fans as it chiseled away at the ’76 season, ultimately taking a victory at the Swedish Grand Prix’s Anderstorp Raceway.

The newly-built P34 follows Tyrrell’s exact plans to a T (other than the original titanium roll bar, which contemporary rules mandate must be made of steel).

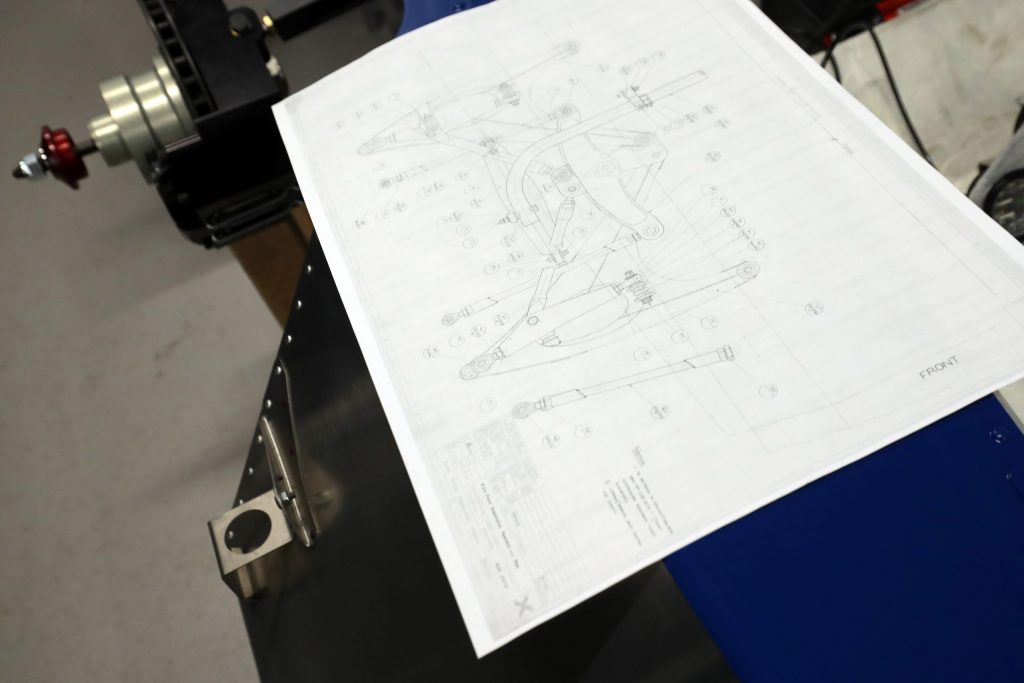

The car’s owner, Jonathan Holtzman, gained the blessing of the Tyrrell family and was granted access to the original build documents for the 1976 chassis. No less than 230 original technicals drawings had to be pored over, so that CGA could exactly follow Derek Gardner’s blueprints.

“This is an exciting new chapter in the Tyrrell P34 story,” said Bob Tyrrell, son of famed F1 constructor Ken Tyrrell.

“Jonathan couldn’t have picked a more difficult car,” Alistair Bennett, project co-ordinator, told Motor Sport. “But that’s him: he loves the details.

“The 1976 Autocourse says that one of the major hiccups with P34 was how difficult it was to build each chassis. Dad [Colin] took great pleasure in reading that out as our first tub went more than six months behind schedule.”

To ensure everything was interpreted correctly, CGA drafted in John Gentry, an experienced designer and engineer who worked on the six-wheeled Tyrrell race car in period. He was tasked with ensuring that the complex build went according to plan.

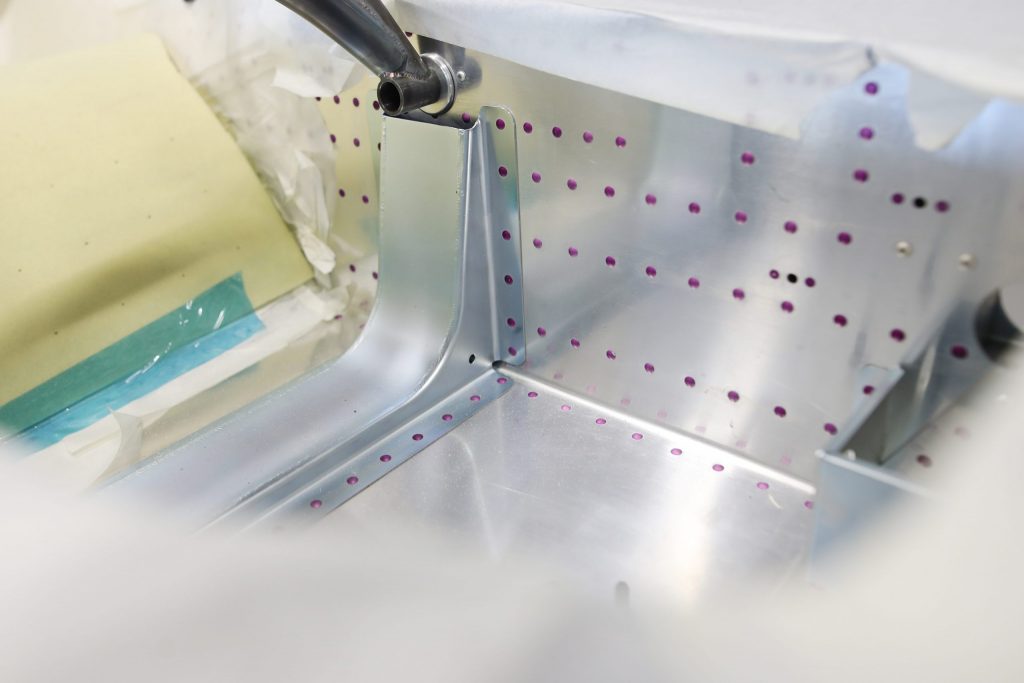

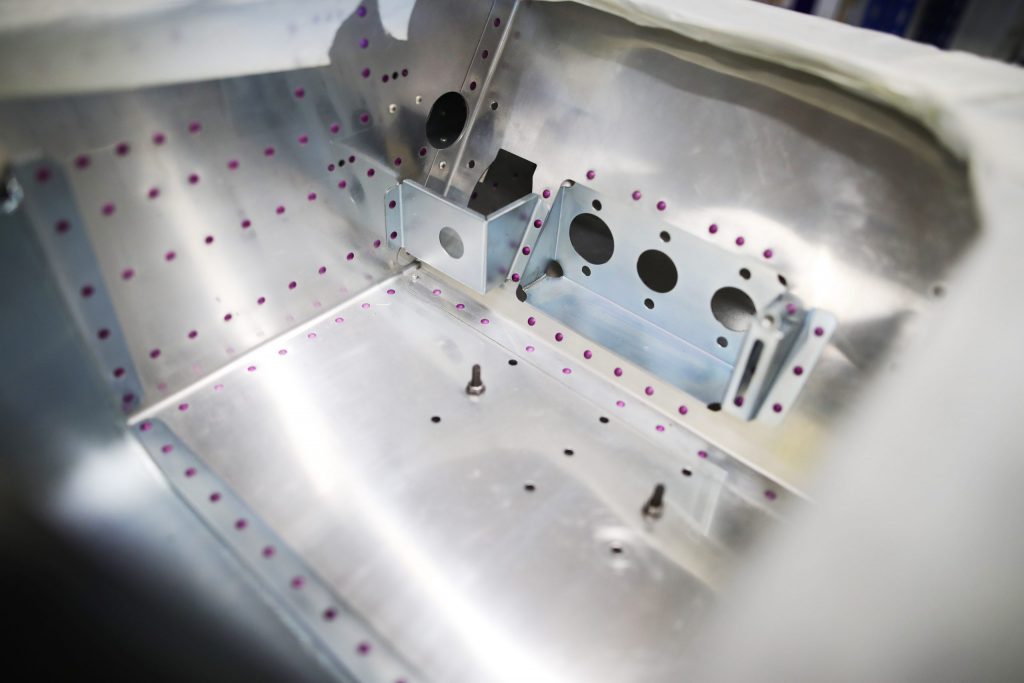

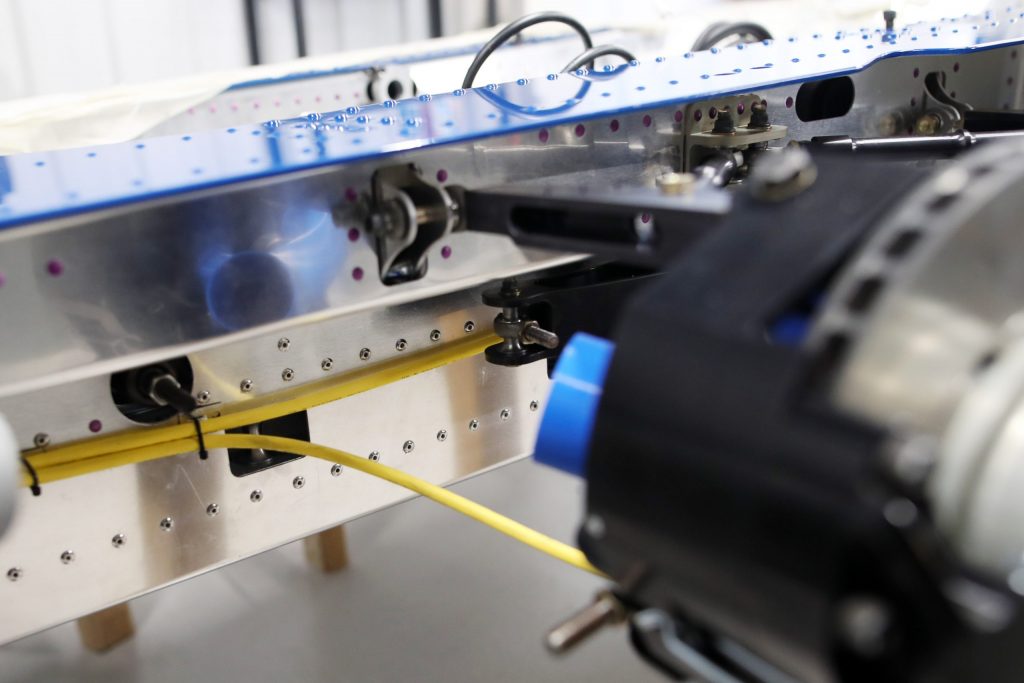

CGA used everything it could to bring the P34’s unique chassis back to life. While every piece on this particular P34 is newly-machined and constructed, the race team 3D scanned many original parts and an original chassis to reverse engineer the six-wheeler and its various continuation parts. The juxtaposition between the slide-rule-and-pencil engineering of the ’70s and the comparatively immense technology used to decipher it is fitting for just how impressive these machines were for their time.

To source raw aluminium sheets large enough for the frame, CGA had to contact Boeing, which was the only other company using pieces large enough to fashion into a P34 chassis. While CNC routers and mills have replaced some aspects of the process, the puzzle pieces are still authentic to their 1976-spec blueprints and materials, thanks to CGA’s research and attention to detail.

Despite the advantages of hindsight and technology, though, the core chassis still took 800 man-hours to construct. Since the project began in 2018, CGA in total sunk 7000 hours into the reverse-engineering, design, and construction of its continuation P34.

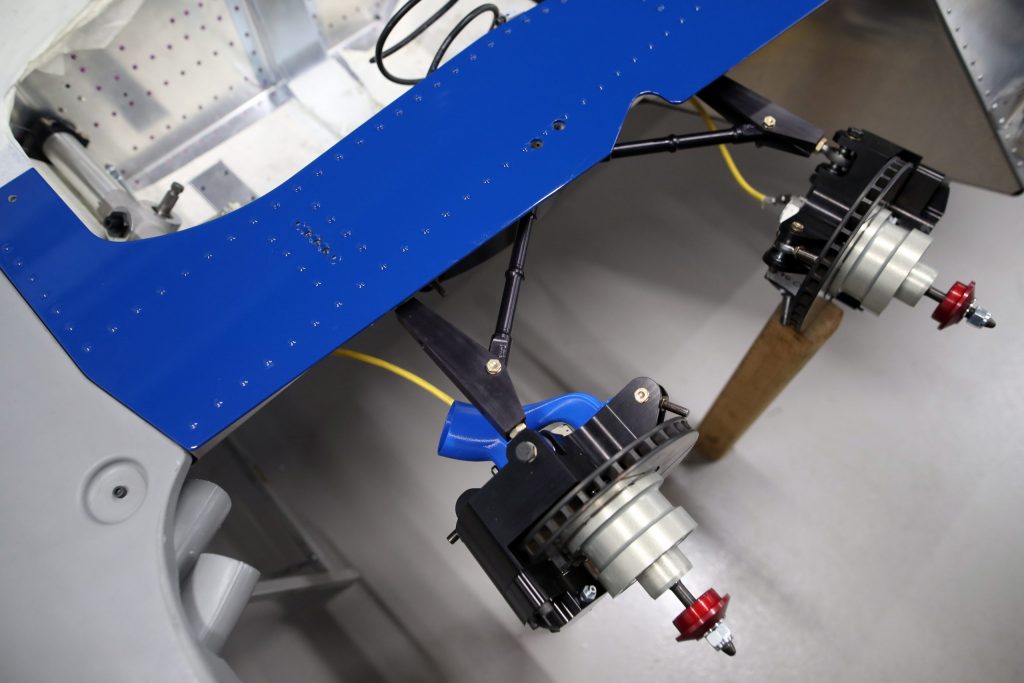

Once complete, the continuation car was tested by James Hanson, an experienced driver and dealer of historic racing cars through his company Speedmaster, last month. His feedback was positive. “From the very first lap the P34 gave you the confidence that it was going to look after you and encouraged you to push on. At low speed it’s slightly vague in terms of placing it – I still haven’t figured out which set of wheels to aim at the apex – but it’s probably best not to over-think it.

“It’s very stable in the quick corners. Because of those small sidewalls it responds more quickly to steering inputs than do four-wheeled cars.”

Normally, losing a front tyre would be disastrous for an open-wheel race car – a race-ending setback that typically concludes in a disappointing return trip to the pits or, worse, a visit to a gravel trap. Thanks to the Tyrrell’s four-wheel front suspension design, however, the P34 managed to limp back to the pits like an insect missing a leg – down, but not out for the count. Driver Jody Scheckter was behind the wheel of the P34 in the 1976 Swedish Grand Prix when one of its 10-inch Goodyear front tyres freed itself from the wheel and rolled off-course. Scheckter, who would continue on to win the race after a pit stop to replace the tyre, told DriveTribe that the P34 had “a bit of understeer” as he drove the car back around to the crew.

“I think everything was a challenge,” Holtzman said, summing up the task of building the continuation Tyrrell six-wheeler. “I wasn’t the one who asked, ‘can we do this?’ I wanted to buy a P34. I wanted to drive one. We tried to buy one for a lot of money, but the owner said no. Alistair [Bennett, director of CGA Engineering] was the one who said that we could make two. Alistair, James, everybody that made the parts – they’re so talented. I didn’t bring that talent. I brought the American ‘we can do this’ attitude.”

Today’s F1 cars are strictly governed by a complex set of rules, and it took outlandish machines like the P34 to help the sport evolve. Tyrrell’s innovative approach challenged conventional thought, but its efforts were cut short when the motorsport rule book closed shut on its advancements.

Last weekend, the new P34 made its racing debut at Brands Hatch, with Holtzman at the wheel, and ran without hiccups – even setting a fastest lap for its class during its first race. As vintage racing returns to the schedule in 2021, Holtzman and the team at CGA plan to enter more vintage races. Until then, dig through our detailed gallery of build photos to see every nook and cranny of the P34, like you’ve never seen it before.

Via Hagerty US

Awesome read, awesome job… awesome car! Your story tag misspells Tyrrell though.

I’m building a 1:12 scale Tamiya P34 and plan on modifying it with realistic hoses and wires. Would you know anywhere I can find a diagram or photo of these ?

I’m looking for the same thing(s) for the same reason. I’ve built two other 1/12 scale, earlier cars and information on wiring and plumbing was reasonably accessible. I’m particularly interested in how these, including brake plumbing, were routed. I think I read that wiring was left to the guys in the factory. Did you have any luck? Part of the problem is that the P34s entered in Vintage races are substantially replumbed and rewired. I’m interested in the 1976 cars in original states. CGA being masters of authentic rebuilds, it’s great to have their photos of the ‘tub’ in the public domain, but unfortunately I’ve found next to nothing on the original rear subchassis hanging off the DFV.