As soon as Hans-Joachim Stuck tried out the first working prototype of the company’s dual-clutch transmission, he knew that Porsche was on to a winner.

The German racer and test driver was immediately convinced by the Porsche Doppelkupplungsgetriebe (PDK) system, fitted to a 962 race car. “Oh, it was wonderful,” remembers Stuck, “because you could concentrate on driving, keeping your hands on the wheel. These cars had loads of downforce doing fast corners, the steering force (was huge) and then you had to take off the hand from steering to shift you, so this was one big advantage.

“The second advantage was no more mis-shifting because before when you made a mis-shift, it could be expensive. And third of course is the most important one it saved a lot of kind of time because when you shift normally you have to go off the throttle. The turbo boost goes down, you put the clutch in, pick another gear and go on the throttle and it takes a while for the boost to come. With this, you could leave your foot down shifting up and it was fantastic.”

One might think, with these clear advantages over a manual transmission, the PDK would have been rushed out to every Porsche race team and into series production for road cars. In fact, this ingenious transmission’s gestation period would be rather lengthy.

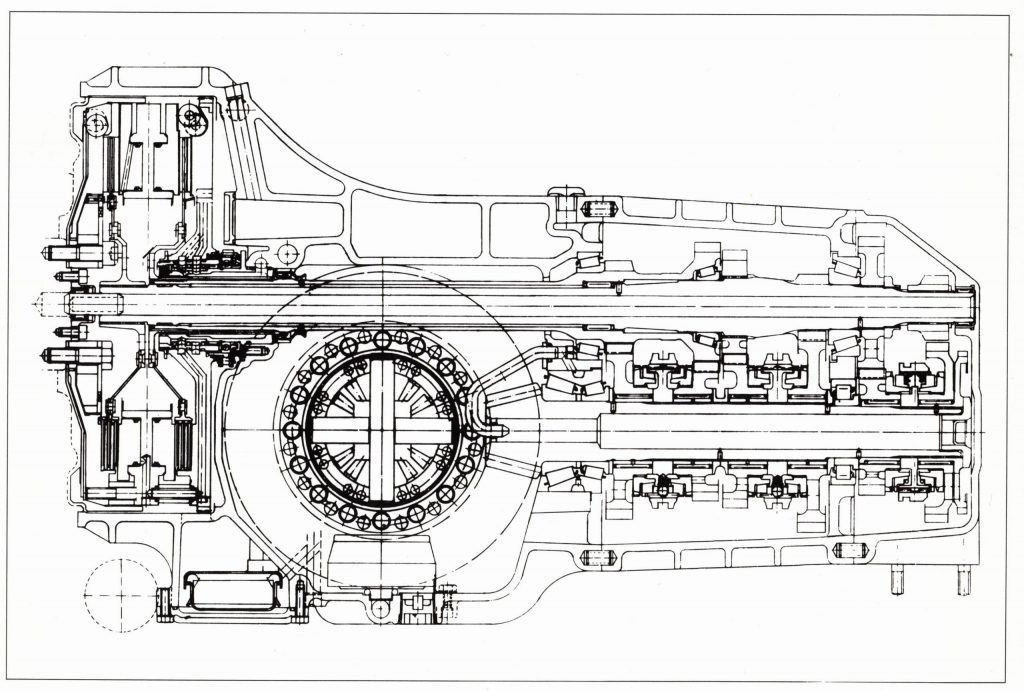

“Sometimes technology takes a long time to mature. Porsche was a pioneer – 20 to 30 years ahead of its time,” says Rainer Wüst who worked on the project throughout this time. Engineers had initially come up with the idea of a dual-clutch transmission as far back as 1964, but control of the actuators was the limiting factor, so it wasn’t until electronic control systems came into use in the early 1980s that the concept began to look practical.

At the time, other car makers and their suppliers had also been working on automated manual gearboxes with a single clutch. The automated manual has its origins in early clutchless manual transmissions that began to appear on mass-production cars in the 1940s and 1950s, and became noticeable in car-enthusiast circles when the likes of Aston Martin, BMW and Ferrari used it with high-performance models. But poor clutch control, whether making a three-point turn or going for a full-throttle upshift, and the associated operating life of the clutch did not go down well with drivers.

During 1981, Porsche’s engineers set to testing dual clutch systems in the company’s road cars, first with the 924 and 944 featuring modified stick shifts that required a simple push or pull to change gear with no clutch and no lift of the throttle required. Among those to experience the PDK in its early days was VW Group boss Ferdinand Piëch who immediately requested the system be developed for the Group B Audi S1 Quattro which would go on to dominate world rallying.

In parallel, Porsche was able to put the PDK to the test on the circuits of the world in its 962 sports car. On its very first outing at Monza in 1986 the car, now fitted with a push-button selection system, took the checkered flag with Stuck and Derek Bell sharing driving duties for the 360km race. By the end of the season Bell was world champion.

The technology was a proven success, but Porsche simply didn’t have the resources at the time to produce the PDK for the road cars that customers could buy, and the first car in showrooms to be fitted with a dual-clutch transmission was actually Volkswagen’s Golf R32 of 2003.

Porsche would have to wait until 2008 before PDK was offered as an option, starting with the 911. A year later the Panamera was launched with the system quickly proving to be far more popular in this grand tourer than the manual option.

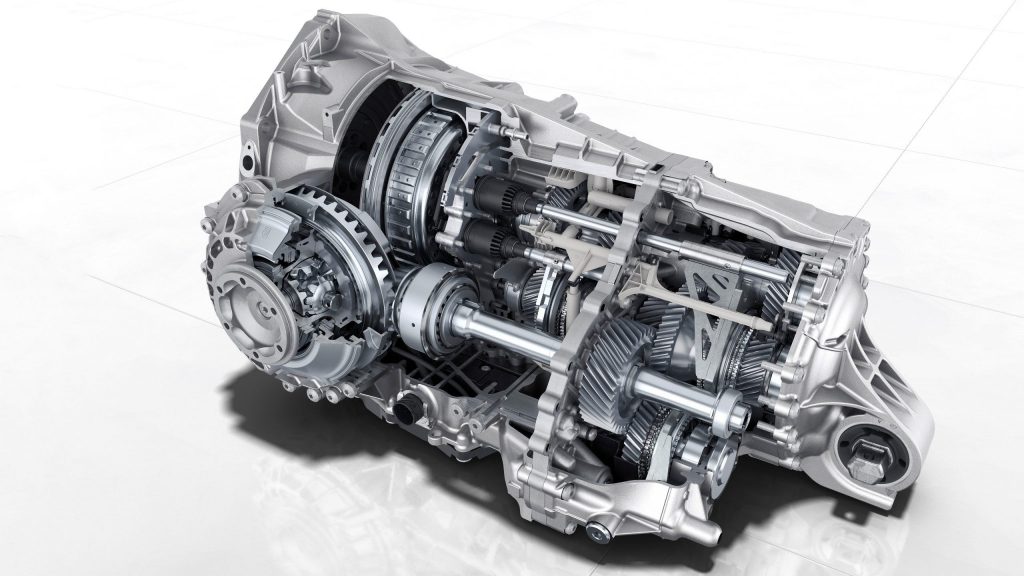

Today, every Panamera and Macan sold is fitted with a PDK and three-quarters of 718 and 911 models globally are also ordered with this transmission. It’s no wonder as it appears to provide the best of both worlds: manual control when the mood takes you, and automatic shifts when you just want to sit back and let the technology take care of things.

A PDK weighs a bit more than a manual and does require a little more energy to operate, as actuators shift gears in replace of human hands, but on the upside the system can be programmed to shift in the most economical fashion to save fuel. The robotic operation of the twin clutches also means shifts can be engineered to be smoother than most drivers could manage balancing clutch, engine revs and gear selection. It can also be operated in full manual mode, allowing the driver to redline the engine in every gear, if desired, for maximum performance and fun.

Compared to today’s best conventional automatics (like the ubiquitous ZF eight-speed) the advantages of the PDK for smooth, fast shifts and manual selection might appear to be reduced. Not so, says Christian Hauck, head of alternative drives at Porsche, who believes that the system still has a future.

“You’re never going to have a launch control possibility with an automatic transmission,” he says. “Plus, one very important thing for us is that we have the possibility to change gear ratios on every single gear that we are having in the gearbox, so we can really make it suitable in the perfect way to every car that we apply the PDK transmission to. And high revs are not really possible with automatic transmissions, with the PDK you can go up to 10,000 rpm. In the GT3 we are already revving to 9000 rpm.”

As Porsche accelerates its electrification, the PDK will be the only transmission for its hybrid vehicles, while the two-speed transmission fitted to the all-electric Taycan (and future EVs) also used learnings from the PDK program.

The 40-year journey of PDK development was not always smooth, and certainly not as swift as Porsche may have planned but Rainer Wüst is certainly glad he persevered.

“Every time I see a Porsche with PDK driving on our roads, I’m happy that there’s a bit of ‘Wüst’ in it,” he says.

Via Hagerty US

Read more

The likely lads in a lock-up who made it to the F1 grid

How the BMW M1 Procar championship was dreamed up over beer and whisky

Peter Stevens: Designing the Jaguar XJR-15 road-going Le Mans racer – in a car park after work