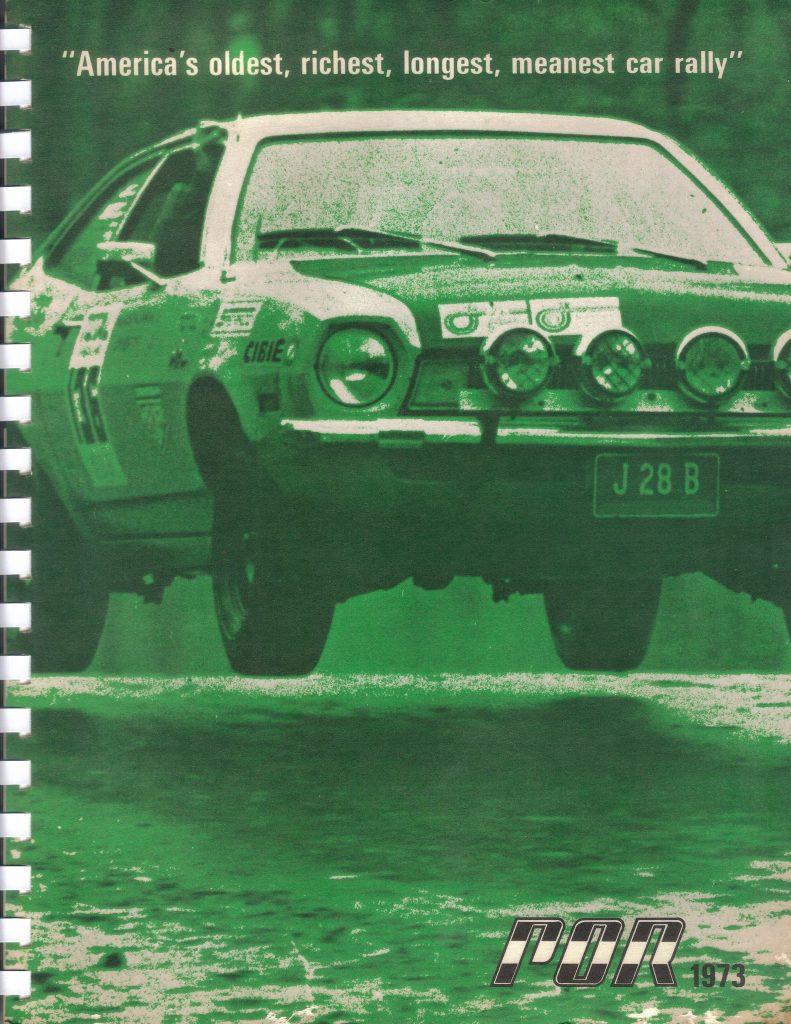

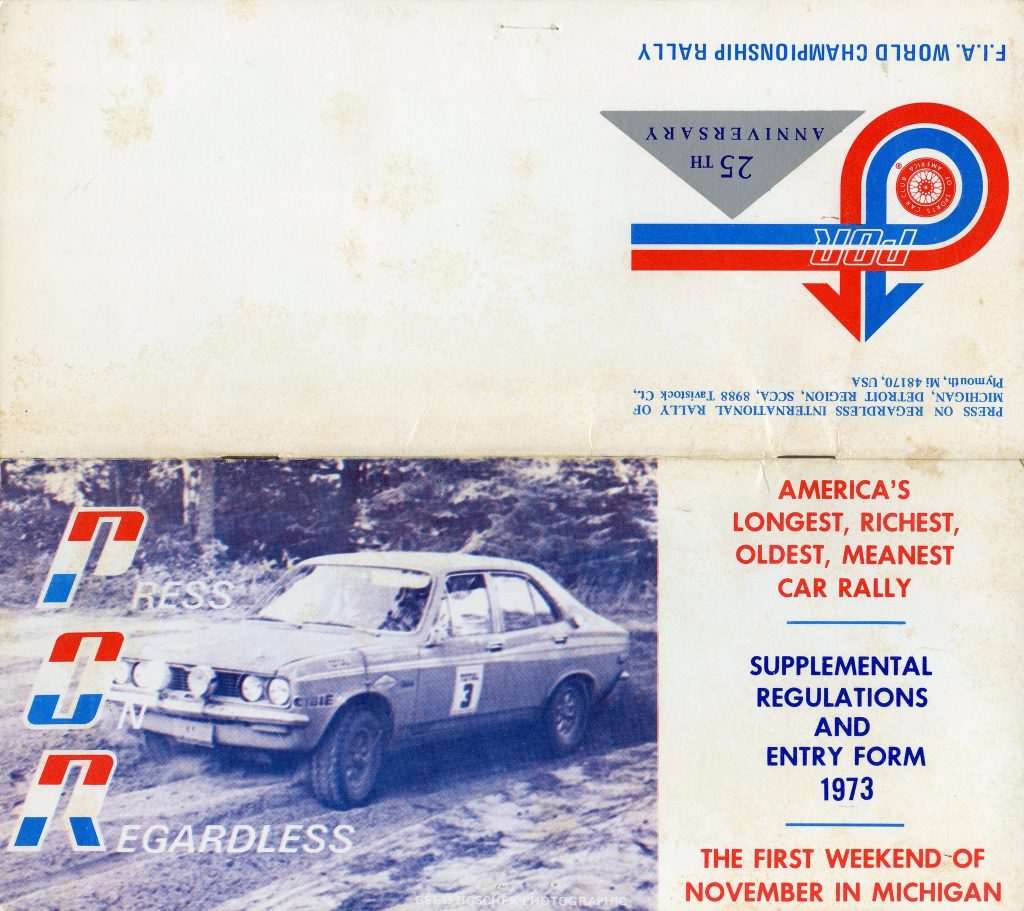

The field at the 1973 Press On Regardless rally (POR), held in the sandy terrain of backwoods Michigan in the US, could not have been more varied. The Datsun 510s, Volvos, and Subarus were to be expected. Likewise privateer and subsequent rally legend John Buffum and his Ford Mk1 Escort RS 1600 were right in their element. More surprising was a hulking Jeep Wagoneer driven by 1972 POR winner Gene Henderson, a friendly bear of a man who was also a fierce competitor.

But at the end of 345 gruelling miles of special-stage rallying, with the total course encompassing 1700 miles, the unlikely victor was a little white mud-spattered Toyota Corolla 1600, campaigned by two privateer Canadians on a shoestring budget. It was Toyota’s first World Rally Championship victory.

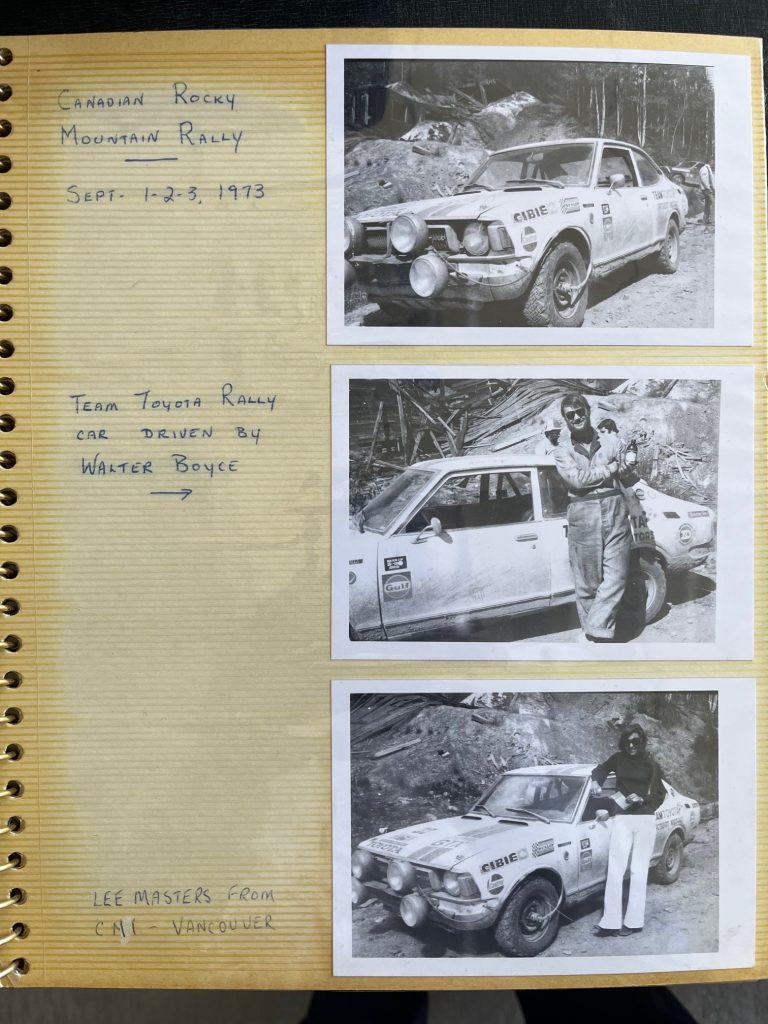

“It’s like I would say to my students when I was coaching ski racing,” says Walter Boyce, driver of that Corolla 1600 coupe. “All you’ve got is your own gravity – so just don’t ever slow down.”

Boyce and co-driver Doug Woods beat the 56 other entries handily, finishing 24 minutes ahead of the next-closest team. Further, POR was known as a serious car-breaker, billed as “America’s longest, richest, oldest, meanest car rally.”

Boyce disputes the rally’s reputation somewhat, though that year’s results tell a different tale: 57 entrants, 34 retirements, just 23 finishers. But by 1973, Boyce had built a reputation as a driver who was smooth as well as quick behind the wheel. More importantly, despite his philosophy of staying off the brakes and keeping momentum up, he had that all-important quality so needed in privateer racing: mechanical sympathy.

“I’d always been good at getting the car to the finish,” he says. “You didn’t want to break things like the factory teams could afford to. It was my car, after all.”

Boyce started seriously rallying in Canada in the late 1960s, taking advantage of a generous contingency programme offered by British Leyland. Campaigning an MGB, he placed high enough to earn bonuses that allowed him to buy a Datsun 510 – and an engagement ring for his future wife. (That turned out to be an excellent move, as Mrs. Leslie Boyce appears to have been quite understanding of her husband’s motorsports obsession, as we will see at the end of this story.)

Datsun was a logical next step, as the company was also paying out contingency money on wins with its products. Partnered with Doug Woods as a co-driver, Boyce won the Canadian national championship for the first time in 1969. He’d go on to win it four more times.

When the money dried up at Datsun, Boyce approached Toyota. Then known in Canadian markets as Canadian Motor Industries, Toyota Canada was about 10 years younger than its US counterpart, but executives were willing to take a risk on rallying. Especially with import brands like Volvo and Subaru, rallying was a popular sport with a broader following than it enjoys in modern days, and wins could burnish a brand’s reputation.

Thus, in 1971, Boyce bought his first Corolla. It was not an immediate success. The engine mounts weren’t up to the task of rallying, and when the car launched over a frost heave during the 1971 B.C. Centennial Rally, the engine lurched forward on landing and put the fan blades right through the radiator.

At this point, the spirit of MacGyver surfaced, 14 years before the show would air. A cable was run from the back of the transmission tunnel and looped around the firewall to prevent the engine from further forward lunges. Boyce and Woods had been forced to retire from the B.C. Rally, but they went on to win the Canadian championship.

By 1973, this Corolla was somewhat worn out by its repeated rally wins. That’s literally worn out – the floorboards had nearly been ground off by abrasive gravel. A new Corolla was purchased and modified with twin downdraught carburettors and an electric fan.

With the assistance of a few friends, the T-50 four-speed clamshell transmission was split open and a kit was installed to give the car a fifth gear. Power was still modest at a little over 100 brake horsepower, but Boyce says that reliability rather than outright punch was of far greater concern.

Woods headed down to POR ahead of Boyce and began developing a set of pace notes with another driver. Unlike European rallies, where they were an absolute necessity, pace notes were unusual for North American rally drivers, and indeed Boyce had never used them. But he says navigator Woods was brimming with confidence that the conditions would favour his driving style.

The first bit of luck for the Corolla was a piece of bad luck for the Wagoneer team. While the Jeeps had muscled their way through the previous year’s rally, with V-8 power and four-wheel-drive trouncing the lightweight sports cars, this year they’d come to the starting line with specially prepared racing engines. Unfortunately, the factory oil pickups didn’t match the larger oil pan sumps, and engine failure caused early retirement. That meant it was up to the Corolla to beat the Datsun 240Zs, RS Fords, and even the actual Alpine A110 1800 that had won the Sanremo rally in Italy that rear, clinching the overall WRC championship for Alpine.

But from the start, the Corolla flew. On the first night, it had set nearly all the fastest special stage times, and was convincingly in the lead. The only real reliability issue was a leaking heater hose with just a few stages remaining, but Boyce was able to swap it for a spare and keep his foot down. He won, Toyota’s Canadian contingent were beside themselves with delight, and somebody got on the phone to headquarters in Aichi, Japan, and let executives there know that the littlest Toyota for sale in North America was now a bona fide WRC winner.

A telegram of congratulations arrived immediately, followed by an invitation to Japan. The Boyces were fêted by Toyota’s brass, and had a chance to visit the company’s Toyota Racing Development workshops. Like any smart privateer racer, Boyce filled his luggage with every TRD part he could get his hands on, then headed back to Canada to start building his next car.

That car was a Celica, and it was in fact Mrs. Boyce’s Celica, the same car that had brought their daughter home from the hospital. Boyce and a few friends tore it apart, choosing a reliable T-50 transmission again, fitting the car with fibreglass wing flares, and building up a potent twin-cam engine good for around 180 horsepower.

“I’m not sure what I bought my wife, but I’m sure I had to get her something,” Boyce laughs. “I suppose it helps that a Celica wasn’t the most convenient car for carrying a baby around in.”

He continued to contest North American WRC events with this Celica, finishing third in the Rideau Lakes Rally behind two factory Lancias, one of them a Stratos; not bad for a four-cylinder Toyota. Boyce rallied into the mid-1980s, winning Group A championships. He was inducted into the Canadian Motorsport Hall of Fame in 2003.

The Celica was sold to Toyota Canada, and it went on to win Canadian championships with Finnish-Canadian Grand Master rally driver Taisto Heinonen at the wheel. Boyce also sold off the plucky Corolla that gave Toyota its first WRC win, but it’s unclear what happened to the car after that.

Toyota’s official rally team would notch its first WRC win 1975, at the 1000 Lakes Rally in Finland. In the 1980s, it would win the Safari Rally several times, before the ascendancy of Carlos Sainz and the all-wheel-drive Celica GT-Four. In 1993, Toyota won its first WRC manufacturer’s title, and repeated the feat in 1994. The year after that, the Sega Rally Championship arcade game brought Toyota rallying to fans of all ages.

To date, though, only one Canadian driver has ever won a WRC race, and Walter Boyce did it behind the wheel of the most modest of cars. But the momentum he and co-driver Doug Woods started for Toyota has continued all the way to today’s modern GR Corolla. It’s easy, Boyce would say: Just don’t ever slow down.

Wonderful piece of unlikely history, thank you.