It’s 2042. Society is beginning to live with the effects of a changing climate. The mass migration northwards has long since begun, but today’s political parties, and the electorate, are less averse to their new neighbours than they were two decades earlier. Social movements started by Gen Z were kicked into overdrive by Generation Alpha, fossil fuel vehicles are now few and far between, and we’re all driving around in electric… wait, Nissan Bluebirds?

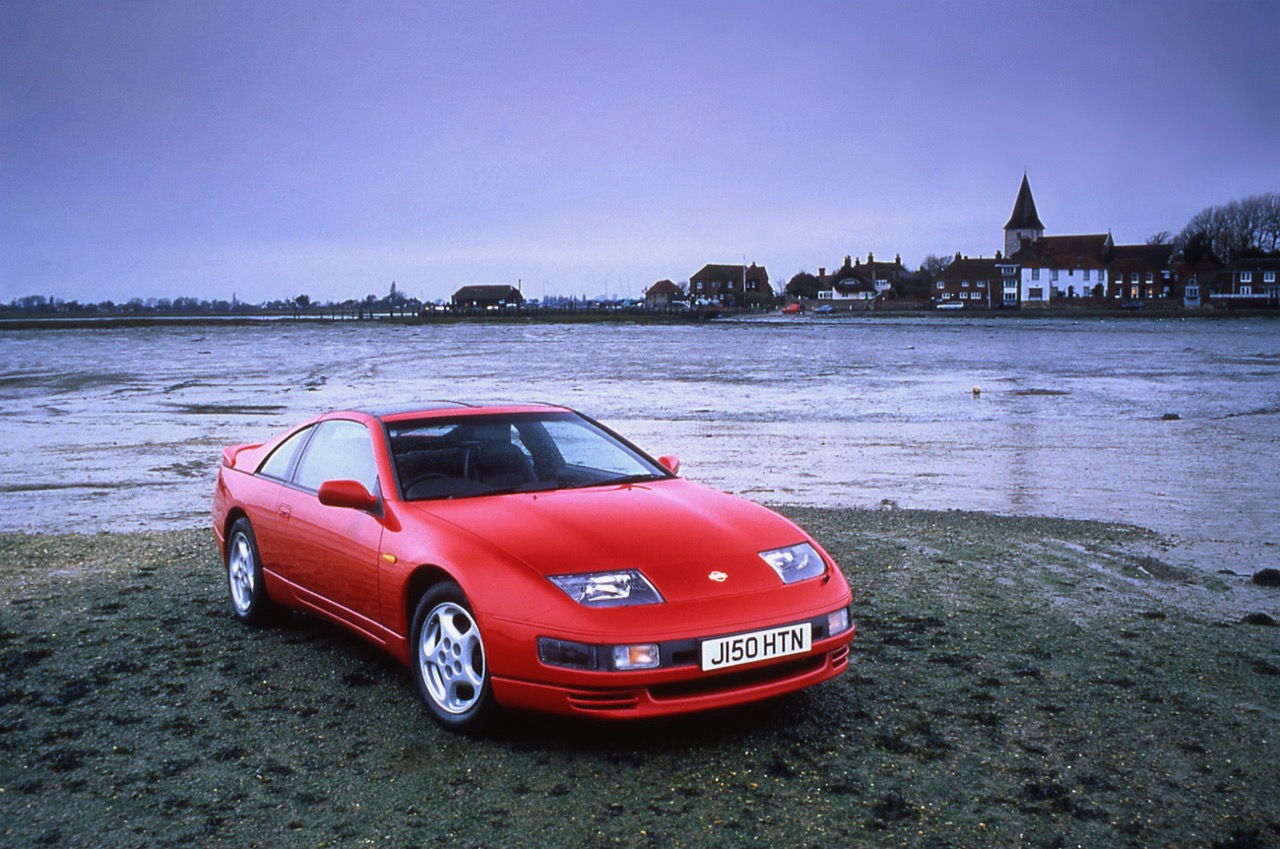

Some scenarios are more likely than others. The pool from which to draw 1980s Nissans for future-proofing is already a shallow one, let alone in another two decades, but it’s an unlikely vision of the future previewed by Nissan’s latest batteries-included toy.

Although it was sold and marketed as a family car to rival Cavaliers and Sierras, most of us will be familiar with the Bluebird because, in years passed, it has served as a minicab or licensed cab. Operators chose it for the simple reason it was cheap to buy, dependable to run, and parts were available. One of the first questions any seasoned user of minicabs would ask of the driver was: ‘How many miles has it done, pal?’ When you found one that had done over 500,000 miles, it was perfect pub talk fodder.

There were no signs of plastic pint glasses and half-eaten donner kebabs in the back of this converted electric Bluebird, and no smells of… well, let’s just leave that to the imagination. The unique – it’s the only one we’re aware of – Bluebird is nicknamed the ‘Newbird’. The brightly-coloured hatchback was built to celebrate 35 years of its Washington plant in Wearside. Bluebird production kicked things off back then, and everything from Primeras to Micras to Jukes has been built in the northeast since.

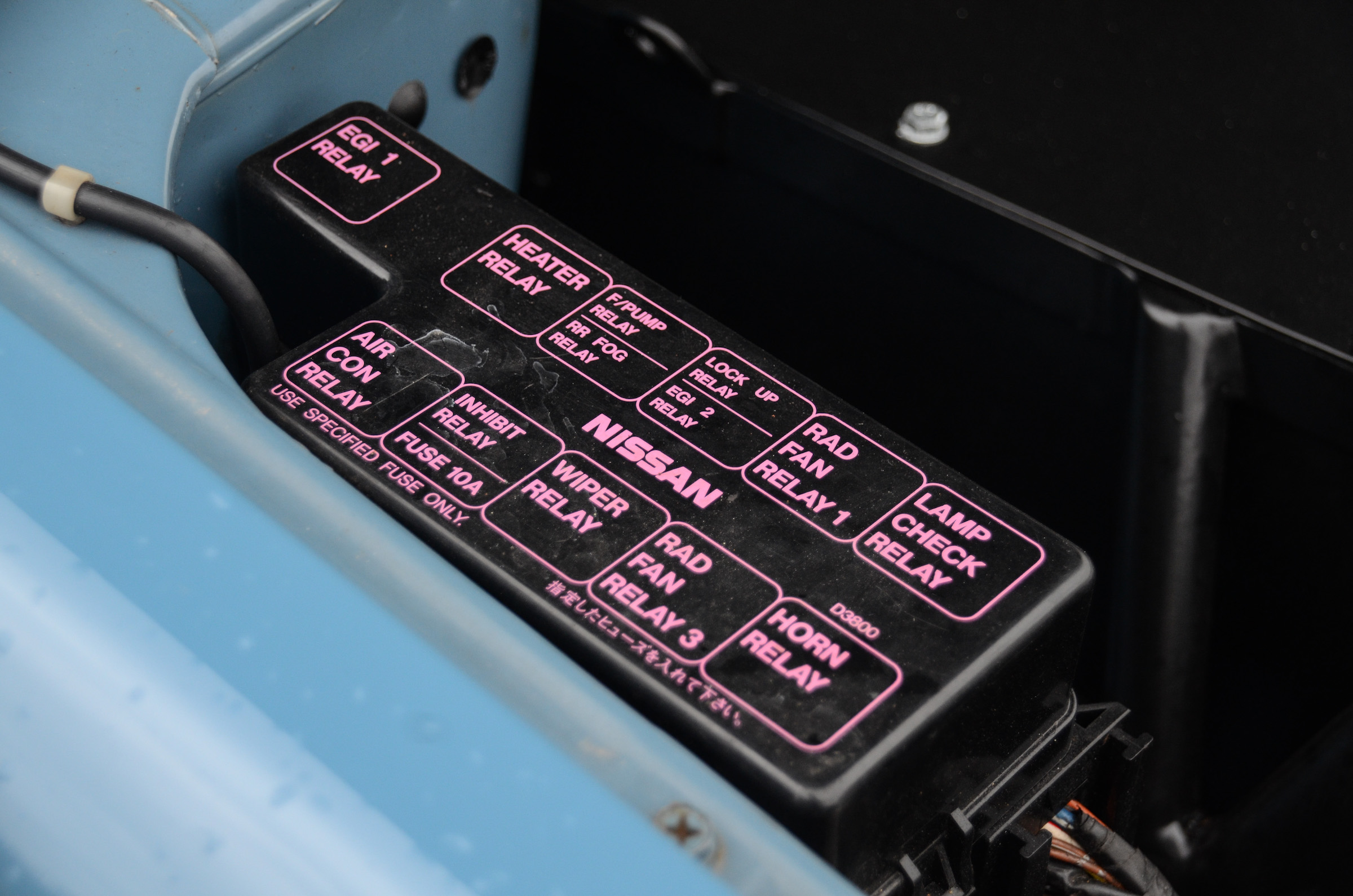

That also includes the Nissan Leaf, whose whirring innards you’ll find under the somewhat less aerodynamic nose of this 1988 Bluebird. The Leaf has been with us now for eleven years, the earliest cars now old enough and cheap enough that conversion firms are beginning to greedily eye up electric entrails like motors and battery controllers.

Durham-based Kinghorn Electric Vehicles is the firm doing the snaffling in this instance, gutting a crashed Leaf for its motor and inverter, and raiding the Nissan parts bin for some newer lithium-ion cells from the current Leaf. The Newbird hides 40kWh of batteries – good for a range of roughly 130 miles – and drives its front wheels, something both Bluebird and Leaf have in common.

Newbird is functional rather than decorative. There’s no Cyberpunk-style dot-matrix lighting or Blade Runner ramen-bar cabin ambience like Hyundai’s recent Pony and Grandeur concepts. You’ll search in vain for a nixie-tube instrument cluster or brushed metal trim.

The only cues something’s up are some Vice City exterior graphics – which don’t quite gel with the British Telecom office carpet blue paintwork – and inside, a monolith between the seats, housing a Nissan Leaf drive selector and two buttons.

Kinghorn has plans to find an original Bluebird automatic lever and map the drive, neutral and reverse functions to the relevant positions, but they’ll have to find a new home for those buttons if they do. One operates the cabin heater – now electric – and the other lights up the grille badge.

Also electrically-driven are the brake servo, since there’s no engine pulling a vacuum, and the power steering, as there’s no accessory belt whizzing around to spin a hydraulic pump. In fact, there’s not much of anything under the bonnet. It’s an incongruous mix of old (hefty 12v battery, screenwash reservoir) and new (oddly engine-shaped motor and controllers, part of the battery pack). It’s neat enough, but also weathered enough, that it could all be factory-fit.

Whoever found the donor car deserves some credit though, as it’s in fine fettle. Actually, maybe the guys and gals up in Sunderland deserve recognition too for screwing it all together properly. To the Nissan employee who fitted the driver’s door back in 1988, I salute you; it opens and shuts with a precision some modern cars fail to match.

However, the seats haven’t endured quite as well. After 78,000 miles of arses the foam is compressed down to the hard supports below. Just a little too squashy, under-buttock. Static-generating velour deserves a comeback though, as does having acres of glass around you, admitting plenty of light to bounce off the shiny blue cabin plastics.

Driving the Newbird is eerie when you’re expecting a chuntering engine ahead of you. The Leaf bits mean there’s not even the pseudo-normal experience of engaging a gear with a manual lever as you might with some other recent conversions. Like most production EVs there’s no creep when you relax pressure on the brake either. Just brush the… gas? throttle? accelerator? (Do we need a new word for this?) and go.

Excitement levels are on par with say, a pleasant morning walk to pick up the paper, or perhaps a particularly well-brewed cup of tea. For Newbird, see Bluebird. Not a car that sent contemporary hacks into raptures with its cornering behaviour. It steers easily, doesn’t get too flustered over bumps, and is generally quite charming – the easy-going progress and clear conscience of driving a modern electric car, but without the dystopian glow of a massive touchscreen.

And the motor doesn’t trouble the roadholding. In a world where people pull axles from Teslas and smoke their way to tens at Santa Pod, it’s slightly surprising to find the Newbird hits sixty in – get this – about fifteen seconds.

There are sound reasons for this: it’s an older car (albeit a sturdy one, by reputation), and both Kinghorn and Nissan wanted to avoid twisting the monocoque into a pretzel with excessive torque. And what’d be the point? With more power it’d just expose limitations with the donor car, and it’s not like converting it was cheap – adding to that cost with upgraded wheels, tyres, suspension and more would turn this into a very expensive plaything indeed.

Ah yes, cost. Brace yourself, but also remember Nissan isn’t planning on selling these. It’ll do the press circuit, and then probably end its days ferrying VIPs around the company’s Washington plant, blending the factory’s history with its future. It’s a toy, proof of concept, just a bit of fun. And will probably make people less angry than if they’d done a Skyline.

Anyway, it cost around £35,000 to convert, which is more or less what you can expect from any EV conversion at the moment. As the editor points out, you could buy a new BMW i3, a car we’ve tipped for future-classic status, for that. But clearly, such a sum makes more sense on an E-type than it does a 1980s Nissan repmobile.

The last few years have thrown a spanner in the works in terms of battery and component prices too, so the usual refrain of “conversion costs will come down” doesn’t necessarily apply. But given a few more years – or perhaps another twenty – and maybe a few of us really will be driving around in electric Nissan Bluebirds.

Read more

Classic Nissan Silvia inspires designer’s sleek EV renders

Bad rep-utation: 7 company cars from the Festival of the Unexceptional

Mini announces official electric conversion for original Minis