This week, many of us journos and writers bid a tearful farewell to the simply spectacular Audi R8. As an ‘everyman supercar’ it has filled its brief brilliantly, but like many of its ilk it simply doesn’t make any financial sense for its manufacturer anymore. Mainly because it’s fuelled entirely by that morally questionable liquid we enthusiasts know simply as ‘petrol’.

It had a very decent run, of course, but against a legislational landscape that deters automotive brands from investing any further in the burning of deftly distilled dinosaurs, it, too, has inevitably become one. Destined to be a footnote in a car book or an exhibit in a museum. And while it is a faintly depressing thought to imagine a new car showroom in 2035, where not a single item for sale within it has a noise-making, fuel-burning engine, there is a small light at the end of this decade-long tunnel: the exemption created for ‘micro’ manufacturers.

While the giants like Porsche and Audi may well be forbidden from selling their petrol-driven wares on our fair isle, the government has created a neat niche for ‘boutique’ manufacturers that stay under a 1000-unit annual production threshold, meaning that should you wish to order a brand-new motor car in 2035, with the choice of the precise colour and trim that you’d like, and still be listening to the bark and roar of a fuel-fed motor, then you’ll just have to think more Caterham than Cayman, that’s all. And upon reflection, I really don’t think that’s a bad place for us all to be.

It’s as if the affordable sports car has gone full circle. It pretty much started with Chapman’s brilliant Seven, and it looks like circumstances might very well take us back there, making these cars – and their ilk – one of the very few confections left available to those who wish to buy new and heel-and-toe, rather than charge-and-go. Being the selfless journo that I am, I thought I better check out how this retrospective future might look, by trying it out for myself. I know. It’s a tough gig, but I do the hard yards so you don’t have to.

My weapon of choice wasn’t the Caterham, as brilliant as that car is, but something produced a little closer to home: the GBS Zero. Built just down the road from me in Nottinghamshire, it’s a really interesting case study in where this new niche industry might be heading, and perhaps what we all might want to have in our garages in ten years’ time.

GBS stands for ‘Great British Sportscars’, and it’s one of those wonderful family-run firms that does everything in-house. While understandably not claiming to have created the Seven genre, or indeed to have the badge cachet of Caterham, they’ve had to bring something else to the party instead, and that is a depth of engineering and a desire to take the original Lotus philosophy and bring it bang up to date in terms of materials, technology, and safety, whilst staying true to its design principles. Not an easy tightrope to walk.

The first difference you notice, or rather don’t, is the size. Despite the fact that the proportions of the Zero look instinctively ‘correct’ for a Seven-style car, it’s actually bigger in every aspect. The proof of this being that I can comfortably fit in a standard-chassis car, despite being a ‘well made’ 6’4’ middle aged man. Something that’s impossible in the Caterham, unless I go for the XL chassis with the drop floor option. Apparently, by moving the pedal box and taking out the seat runners, GBS have seated a 6’9’ customer before, which means even if drivers are much taller in the future, they should be able to buy a sports car.

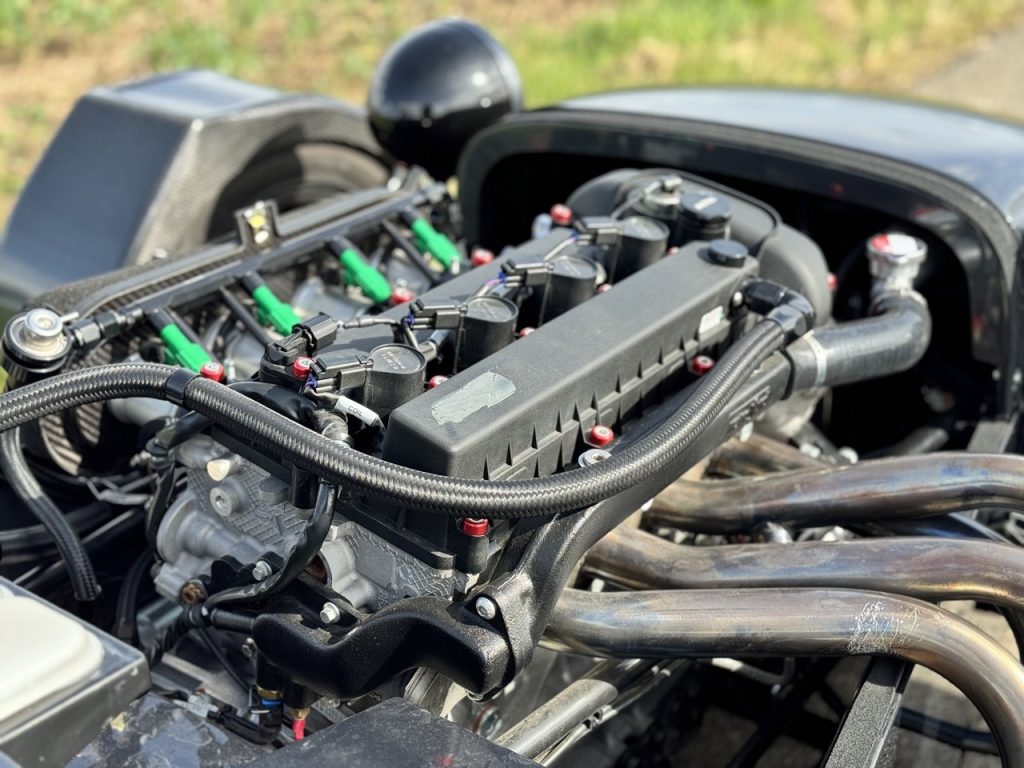

The GBS chassis is worthy of note, actually. As well as being larger and more torsionally rigid than most Sevens, GBS also bond the inner and outer alloy skins to create an effective monocoque. This makes things much stiffer and also adds strength in a crash. The suspension arms are also much longer, giving the car a wider track front and rear, with a fully independent rear axle set-up, and therefore a little more grip, whilst the roll centre and centre of gravity have all been carefully configured to put the driver at the centre of the action. Weight distribution, what little there is of it, is a near-perfect 50:50, and with even the heaviest example weighing in at 600kg, you can imagine the fun on offer from the optioned, front/mid-mounted Duratec engines. With the map and throttle bodies, these are an easy 200bhp, so you can work out the bhp/tonne yourself. ‘Healthy’, in case you’re wondering.

So that’s the Top Trumps stats, but what is it actually like to live with a new-age/old-age sports car as an everyday proposition? If we are all to look to cars like this as our future entertainment, then can they do everything we need them to? Thankfully, a two-day extended test drive would answer all of those questions.

My first day, driving in another ‘blast from the past’ that weathermen apparently call ‘sunshine’, I was able to give the Zero a decent ‘B’ road spanking. Given the spec sheet above, it was predictably brilliant at this. The Duratec proved to be a torquey and willing servant, while the surprising chassis compliance brought about by those long arms, combined with clever damper rates, gave the sticky Yokos plenty to do. With the roof off, and Nottinghamshire’s finest roads at my disposal, I soon made short work of the first 30 litres of fuel in the touring-spec tank. In terms of fun and power delivery, there’s nothing to touch it, really. It feels fast. It IS fast, but more important than that, it has the ability to entertain at any and every speed. If the cameras on your route dictate a strict 60mph, then you’ll still be smiling when you arrive. What impressed more than the inevitable hilarity that’s required to compete in this sector, however, was the car’s innate happiness to cruise at low speeds and on partial throttle openings. This is a car that does traffic even better than it does apexes. Something else that will be important in the future on our crowded roads.

The second day gave me the other acid test of a British sports car: how well it handles rain. The benign chassis dynamics were easily able to make me look like a driving god when the Yokos struggled shifting the fairly biblical amounts of water on offer, but again, I’d rather expected this from the car’s capable CV. What I wasn’t expecting, however, was the supplied ‘bikini top’ and side screens to keep almost all of the water out of the cabin, even when driving through an inch of water, behind rather large lorries.

If this what the future of sports cars looks like, then you can very much count me in. The Zero is ridiculous amounts of fun, is surprisingly easy to fit in, drive, and live with for a car of its type, and although I didn’t get to drive it on a track, one imagines from its performance on the road that it’s more than capable of spanking some quite expensive machinery. You could wait until 2035 to buy one, but my advice is to advance that timeline somewhat and treat yourself to one now. Choose the GT chassis (40mm-per-side bigger) to future-proof yourself against the inevitable obesity that the processed foods of tomorrow will bring, and you’ve got a car that you can easily drive into your retirement, providing you stay limber enough to still get in the thing, of course. Mind you, with the advances in medical science and the inevitable uptake of yoga apps toward the middle of the century, I reckon most drivers will okay well into their 90s.

Just as people didn’t stop riding horses when the car came along, it looks like true petrolheads will still be able to get their fix once the petrol engine becomes a showroom rarity. And if it reminds us all what true driving enjoyment is all about in the process – and strips that back to the very bare essentials that make every journey enjoyable – then maybe it’s not such a bad thing after all.