Have you ever lusted after a Porsche? A Ferrari? An Aston Martin? Who among us haven’t? Moving a little lower down the food chain, perhaps a Hyundai, Toyota, or even a Ford? Chances are I’ve found something in that lot that tickles your pickle, and whether you’ve longed for the view of a Vantage from the veranda or you simply had a RS Turbo poster on your wall as a kid, you’ve succumbed to the genius that is motorsport marketing.

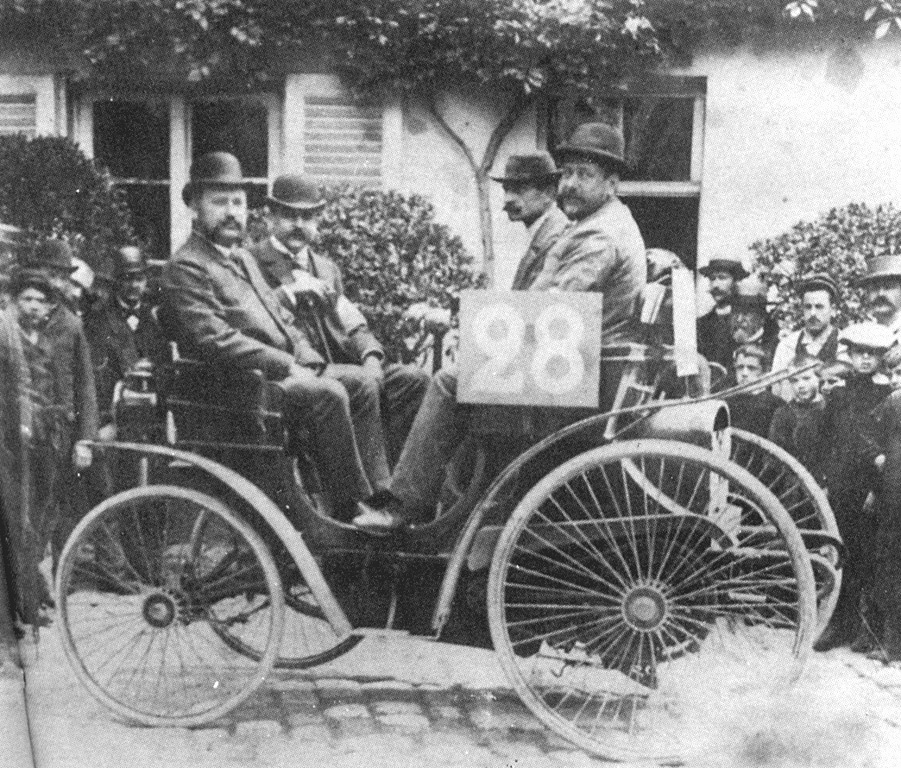

It’s widely agreed that the Paris-to-Rouen road race of 22nd July 1894 was the first proper motorsport competition. Vocally promoted by its organiser, the Parisian magazine Le Petit Journal, it was proclaimed to be a Concours des Voitures sans Chevaux or ‘Competition for Horseless Carriages.’ No fewer than 102 competitors entered, driving a variety of machinery, and after many miles of broken records, broken cars, and broken drivers, two fledgling motorcar makers called Peugeot and Panhard split the prize pot between them. Ever heard of them? Of course you have, because they immediately started telling anyone who would listen how wonderful their cars were, based on this recent victory. And thus, the die was cast: Win on Sunday. Sell on Monday.

Peugeot in particular would go on to be an object lesson in how to transform yourself from a maker of fairly sensible French family transportation into a brand whose wares are feted by collectors to sit alongside their true exotics. Think of the inextricable rally imagery of the 205 T16 that drove GTi sales, or the Pikes Peak 405 that made every sale rep want to trade in his Sierra GL. Or did it though? Because perhaps he’d just watched Andy Rouse perform laps of derring-do in his BTCC-prepared RS500 and instead was off to the Ford showroom to order another.

The link between brands like Porsche and Ferrari and their motorsport lineage is perhaps an obvious one. The sales of their current lineups simply don’t exist without the decades of race or rally wins that not only bolstered the brand image, but also created a useful trickle-down test-bed of technology for their R&D teams. But for ‘lesser’ brands like Toyota or Ford, motorsport success is no less important. While the ‘halo’ models of the RS, ST, and GR ranges may not be the ones you ultimately buy, it’s their literal reflected glow that gets people looking at the brand in the first place. Don’t believe me? Then remember, up until the late 1980s, Subaru were widely regarded as the manufacturer of hardy workhorses for the country and farming classes. Place one fiery Scotsman into a Legacy, bolt on a turbocharger, and suddenly you’ve created a brand image that sees your flagship model selling in the classic car collector space today for upwards of half a million pounds. And Hyundai? Anyone who rode in a Stellar mini-cab in the ‘90s wouldn’t have given you buttons for one, but sprinkle in a little WRC and Nürburgring magic to create the ‘N’ range, and suddenly you’re at the top table of desirability with all the established players. It’s amazing what gloss a little competition can add.

So what’s the worry? Twas ever thus, so will always be, right? Well, we’re going to have to wait and see, because so far going forward, the signs of a similarly symbiotic relationship between sales, marketing, and competition departments look to be on much shakier ground. The way that the business model has worked to date is that the manufacturer invests significant budget into motorsport, often to promote something that looks a lot like the showroom product. Whether it’s rallying, circuit racing, or top-level hillclimbing, they’ll spend the millions because the racing is exciting to watch, which brings television cameras and sponsors, and then ultimately, people, who will all want to own something similar once you’ve won.

With ICE vehicles, this is easy. Cars with traditional engines are great for motorsport. They can run for 24 hours, when needed, at events like Le Mans or the N24. They can be refuelled in seconds in a farmer’s yard on a Welsh rally stage, and they don’t need a huge amount of additional infrastructure to make them work. Also, although they very much can and do catch fire, particularly when crashed into immovable objects or other cars, the management of that fire risk is well understood and easily controlled.

As showrooms start to fill with EVs, manufacturers might look to create a similar programme for brand promotion, and this is where the differences make themselves abundantly clear. Battery-powered vehicles may be fearsomely fast, but they’re also very heavy. They also can’t run at great speed for any prolonged period of time. This means that endurance racing is out, unless battery-swapping technology or physical car swapping occurs. And as for rallying, with its love of remote locations and deliberately challenging topography, where and how will everyone charge after that rudely rapid first stage?

“It’s easy!” say the EV enthusiasts. “Use generators, like Formula E does!” It is a solution, of course; lug a small village of industrial-sized diesel generators to each venue to charge your grid, and away you go. You can see the issue here, of course – as did the Formula E PR team, who quickly had the generators converted to run on more environmentally friendly sugar-based glycerine once the green faux pas had hit the headlines. But if we’re converting those combustion engines to run plant-based fuels, why not just cut out the middle-man and stick it in the cars instead?

Now, assuming that a few trailers’ worth of generators is the way to go, and they’re filled with a suitably Greta-friendly fuel, how will they all generate enough power for a full day of circuit racing? A typical day’s timetable can easily be 9 or 10 races, each with 20–35 cars, meaning around 300 very rapid charges needed across the day’s line-up. That’s a lot of plug time, and while I’m not clever enough to work out all the amps and kilowatts that would take, a nice man on Twitter/X did, when I posed the question there. Short answer: They’re going to be sucking a lot of sugar, let’s put it that way. As for investing in fast chargers on such a scale at most circuits, it will require a significant seven-figure war chest, and the honest truth is, most of them just don’t have it, even if they could muster the required level of amps from the grid in the first place.

Then there’s the racing itself. Between 2018 and 2020, Jaguar nobly attempted to create a one-make series for the I-PACE as a support event for the Formula E calendar. Although the cars looked fantastic in race trim, the resulting spectacle – a field of 2-tonne SUVs whirring silently around a beautifully laid-out, if somewhat soulless concrete lot at the kind of speeds you’d easily hit on your next track day – left most spectators somewhat short-changed. Jaguar cited the Covid pandemic as the reason for canning the championship, but you’ll notice that most other series that paused at the same time came back as soon as racing was once again allowed. Because this is what nobody is talking about: EV cars can be fun to drive quickly, but my goodness, they’re incredibly boring to watch when others do.

So maybe we just need a smaller, lighter car and an evocative venue? Imagine Renault’s latest 5 E-Tech, liveried like the old TS racing series of the 1980s and running door-to-door at an iconic circuit like Donington or Brands? Lack of raucous engine note aside, that could be quite the telly-friendly treat for racing fans everywhere. The only issue is, as it stands, the circuits are somewhat nervous to take them. Just recently, Anglesey famously declined to take EVs on track days due to fire risks and fears of thermal runaway following a crash. A grid full of race cars often comes together during the action, and if a fire starts, burns ferociously, and craters the tarmac or compromises the integrity of a tempered barrier early on in the day’s proceedings, then the race director has a very real problem to finish the day’s schedule on time, particularly if there’s a live – and immoveable – TV slot to fill. It all has to be factored in.

Manufacturers will be able to trade off their hard-won reputations for many years to come, I’m sure. Even if Ford never builds another race car, or Peugeot never enters another rally, they’ll still be able to proclaim their former glories to drive people into the showrooms. My guess is that they won’t have the volume up too loud on those showroom TVs, though. If you’ve just heard the pure engine sound of Ari Vatanen’s Group B 405 climbing Pike’s Peak at full revs, the resulting test drive that follows might leave you feeling a little flat.