There are two people that got me into this game and set me on the road to becoming a fully fledged member of her Majesty’s Motoring Media.

My father, quite rightly, sat me down around the time of A Level results, to have a ‘chat’. My marks would have been laughed out of any university clearing room. It was time for a plan B. A Plan C and Plan D were probably required too.

Retake your A Levels, he suggested, and in the meantime sit yourself down at the Olivetti typewriter and write letters to the editors of all the car magazines that were piled up around my bedroom, asking about the chance of a summer job as editorial gopher – washing cars, filing press packs, sending fax messages and labelling and cataloging 35mm transparencies.

That last bit was harder than it sounds. The nails of my dainty, work-shy hands would end up bleeding from thumbing through all the plastic transparency sheets and arranging the archive in A-to-Z fashion. Fail to do so and the picture editor would let you know about it – especially after he’d come back from a particularly long, beer-infused lunch.

My other guiding figure was, unwittingly, Sir Clive Sinclair.

When I was in short trousers, my parents had friends that lived in Dulwich, London, in a cul de sac. I didn’t have a great deal in common with their daughters, and their parents could probably tell as much.

One visit, presumably anxious about what they were going to do with this equally anxious lad, they wheeled out a Sinclair C5, and suggested I go and have some fun with it.

They’d won it in a raffle. You couldn’t sell the things, as Sinclair found to his cost.

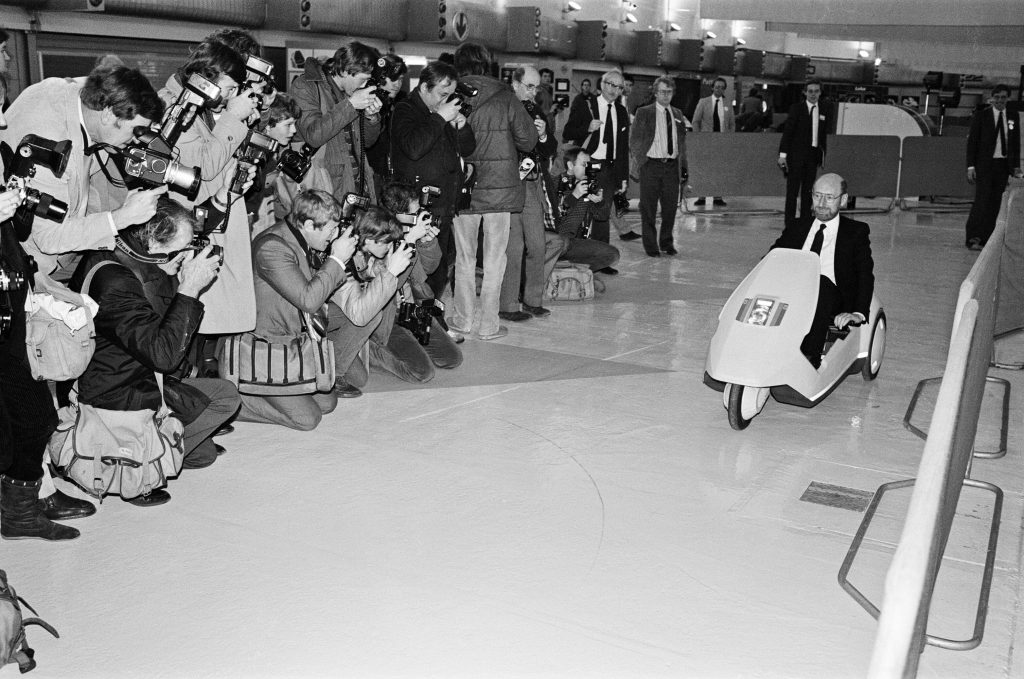

The computing guru devised a polypropylene body that was tough and wipe-clean, and had the chassis designed by Lotus Cars. And in something of a breakthrough, it could be driven on the roads without a licence, insurance or tax by anyone over 14.

Sir Clive had hoped to sell 100,000 a year. In the end no more than 17,000 in total hit the road, and the entrepreneur racked up losses in the region of £7 million, according to The Times. Then there was the damage to his reputation, which never really recovered.

Today you could argue it was ahead of its time – and perhaps it was some comfort that Sir Clive lived long enough to know as much – but at the time the mainstream media lambasted the C5 being a poor man’s Reliant Robin. Critics said it was slower than a bicycle, devilishly difficult to manoeuvre, offered no weather protection and was precisely the right height to be invisible to a trucker checking their mirrors – and precisely the right height to slip beneath lorry wheels.

“Clearly I should have handled it differently,” Sir Clive recalled. “If I had it could have succeeded. I rushed at it too much and invested too much in the tooling and I should have gone a bit more gently into it.”

Pah! What did the British public know?

Back in the Dulwich cul-de-sac, I was discovering the thrill of speed and buzz of throwing around a vehicle, even if the battery was as dead as a dodo.

As a young lad who had a love of cycling, I could peddle the C5 to quite a speed. But then came the revelation; when I reached the end of the downward-sloping road, violently cranking the handle bars (under your knees, remember) and applying the back brake at the same time would tip Sir Clive’s revolutionary personal mobility device into a barrel roll.

Over and over it would go, until it landed back on its wheels. At which point I’d continue in the direction I’d been travelling, feeling pretty smug with myself for pulling off a stunt Evel Knievel would be proud of.

It sounds incredibly disrespectful. But hold on a moment, because if anything it proved how well made Sir Clive’s C5 was. Every time we visited those friends, I spent half a day subjecting the C5 to increasingly hare-brained stunts involving ramps, rolls and generally treating it with the sort of demolition-derby enthusiasm of a budding Euro NCAP crash test engineer.

As I discovered the simple joys to be had from throwing about a vehicle with wreckless abandon, the C5 never missed a beat. Nothing fell off, including my limbs.

Occasionally, and quite unintentionally, I have found myself attempting to repeat those stunts in proper cars. Unsurprisingly, they were nowhere near as up to the job as Sir Clive’s creation.

Today the C5 has become a collector’s item, and I sincerely doubt any of those owners would dare to subject it to the abuse I handed out as a young lad. I also doubt it is what Sir Clive had in mind when designing the C5.

But it was from messing about in that plastic contraption that I first got the bug for playing with cars. And for that, Sir Clive, I will be eternally grateful.

Read more

Planned 1985 production was 100k, capacity at the Hoover plant was upto 8k per week so the 100k per month figure quoted looks wrong. There was a planned C10 and C15 but Sir Clive apparently did little if no market research – otherwise he found have found there was effectively no market for the C5.