Do you ever get that nagging feeling that you could be doing more with your classic car? That sunny Sunday morning drives, occasional trips to events and perhaps even a tour or two with friends in the summer isn’t quite doing justice to the car and your own, deep-seated desire to get out there and really drive?

Alex Childs and Tom Owen recognise that feeling. Both have scratched the itch to do more with their classics, which is how we come to meet bright and breezy at Goodwood Motor Circuit, earlier in the year, for a day of splishing and splashing our way around a drizzle-dampened track.

Both are competitors in the Historic Sports Car Club (HSCC), Childs in the 70s Road Sports championship, Owen in the 80s Sports & GT Challenge. Despite the decade between them, the premise is simple: these are motor racing championships with rules carefully considered to keep costs and the barriers to entry as low as possible, and the cars as close to roadgoing specification as is practical.

It’s an approach that helps preserve originality while encouraging owners to get out there and race – sharing their car for the enjoyment of others huddled on the outside of Madgwick or Paddock Hill Bend, watching as the old timers slip and slide their way around Britain’s most-loved tracks.

Because Childs and Owen are ridiculously generous people, they’ve agreed to let yours truly have a drive of their cars. It’s been a while since I flexed my National A race licence and peered over a pit wall to nervously – sorry – professionally assess the level of standing water on a circuit. Hopefully, though, it will be a great way to find out what more about the HSCC’s championships and how they’re helping bring more people, and more diversity, to motor racing.

1982 Audi Quattro – HSCC 80s Sports & GTs

I start with the Quattro because, well, it’s raining and I am as curious as anyone to know what an Audi Quattro – a car better associated with snow and gravel than a circuit – will feel like around the six right-hand bends and two left-handers that make up a lap around Goodwood.

After all, the weight distribution of an early Quattro, which took a bow at the 1980 Geneva motor show, was often commented on by rally drivers of the day. The likes of Mikkola, Mouton and Röhrl successfully tamed the Quattro, Mikkola especially as he’d done so much development driving during the car’s gestation, but they all acknowledged that its handling could be nose-heavy.

Nose-heavy or not, the Quattro transformed rallying for good. And here’s the interesting thing – the competition simply didn’t see it coming. The ground work was done with the Iltis military vehicle and then the Audi 80, and by the middle of 1978, the VAG board had given the go-ahead for a road and rally car programme which would lead to the development of the Quattro. All this at a time when World Rally Car (WRC) regulations explicitly forbade four-wheel drive.

Audi quietly went about asking other manufacturers in the WRC if they would be happy to rescind the rule, and because they had little idea of how four-wheel drive would prove a game-changer, none of the manufacturers objected to revising the rules, effectively shooting themselves in the foot. (Or, perhaps, team bosses sensed this would actually keep them in business for years to come, as they played catch-up with their own spin on four-wheel drive cars…?)

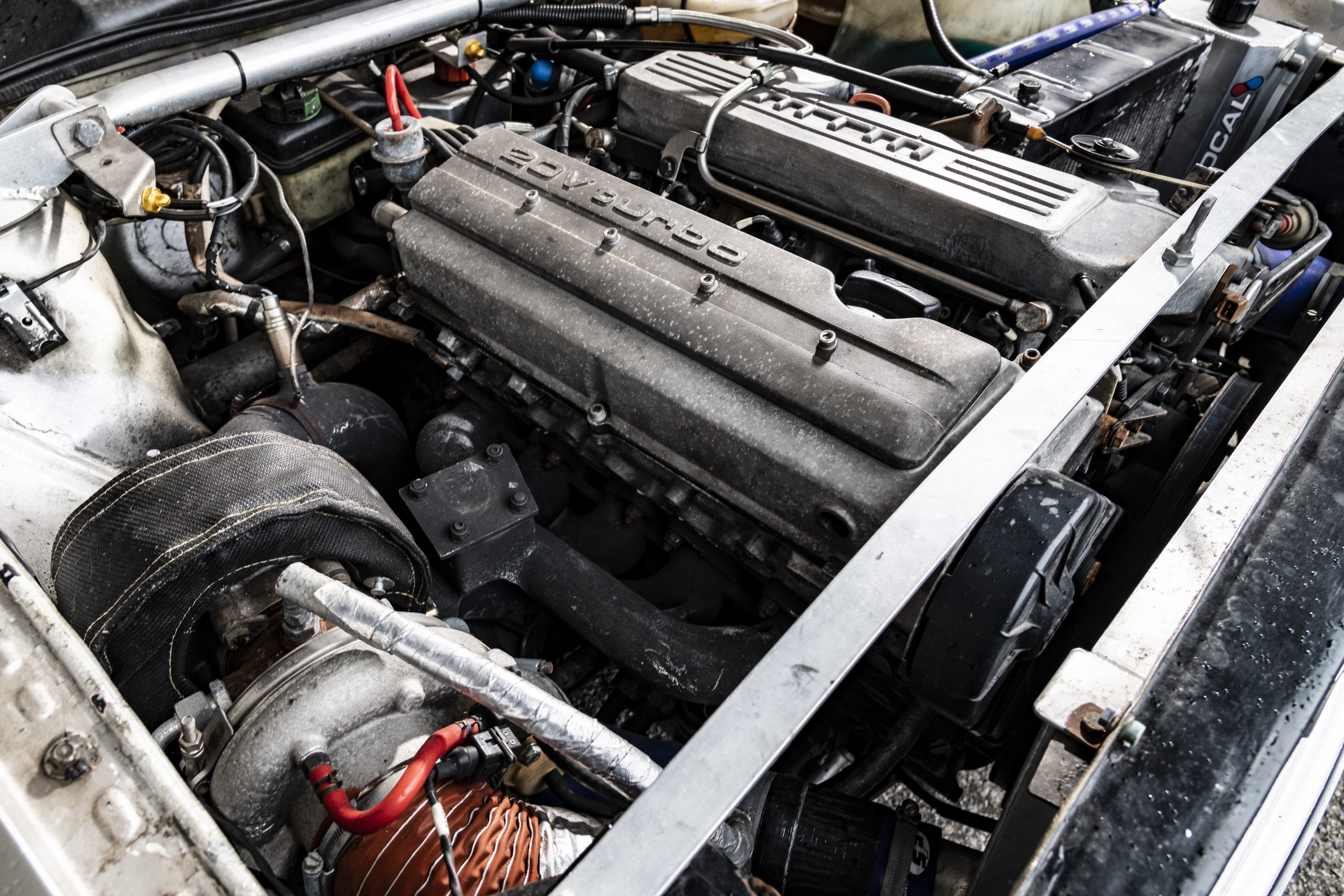

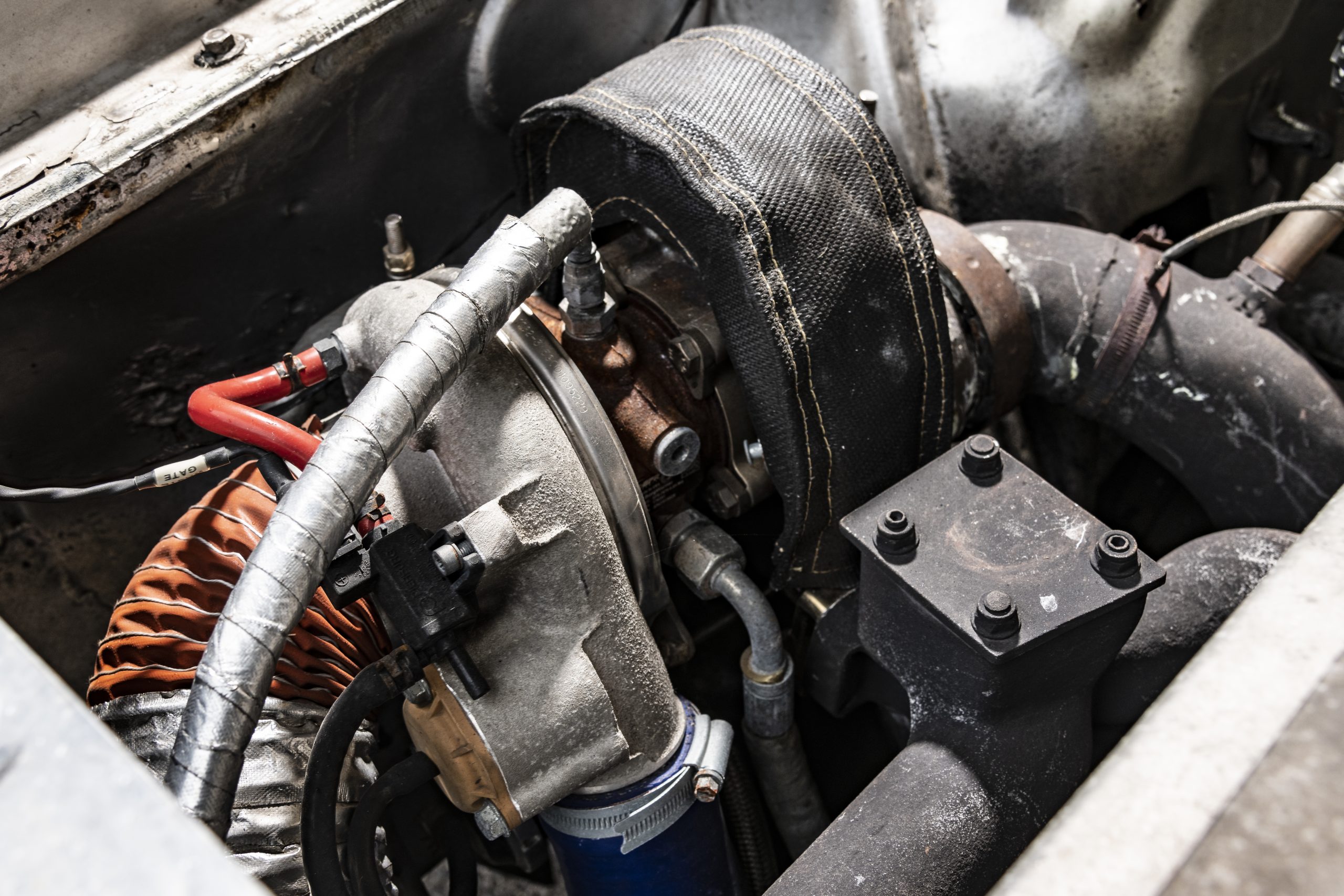

Peering into the engine bay of Owen’s Quattro, you’re reminded of that weight distribution. The inline five-cylinder engine (a 20-valve in this case, rather than the original 10-valve which blew up) sits ahead of the axle line – not just some of the lump, but all of it. The original road car had a weight distribution of 61.3:38.7 front to rear, and a kerb weight of 1246kg.

As an early model, this car originally left the factory in left-hand drive configuration and was converted to right-hand drive in period, which explains why the wipers sweep the other way round. On the back window there’s a Quattro Owners’ Club sticker and another encouraging anyone following to Support Our Lifeboats. Even the aerial is still present.

Because the car has to be largely standard, it’s pretty much as it would be on the road, so there’s still carpet and all trim (regulations state the passenger seat and floor carpets can be removed, if wished), although I note Owen has removed the CD player’s fascia – a humorous token gesture to weight-saving, perhaps?

Period brown plastics and fabrics abound, the pedal set is original and all the switchgear (from foglights to instrument cluster dimming) are intact, but the steering wheel looks to have been swapped in from an Audi S2. For the passenger there’s a Cobra Daytona race seat while the driver gets a Recaro, both with harnesses, and between them rests the somewhat crude looking lever for engaging the central locking differential, while the cabin is finished with a Safety Devices cage, a plumbed-in fire extinguishing system, and extra dials for oil temperature and pressure have been fitted.

The only other thing to note, before strapping in and making my way up the pitlane at Goodwood, is that Owen’s Quattro has at some point had a Porsche braking system fitted – he’s not sure when, or which parts they are, but assures me they work well enough. The tyres are Toyo Proxes R888, one of many road-legal tyres deemed acceptable for the championship by Motorsport UK.

On the track, my first worry is having a shunt. Not into the grass banks, but driving around the driveline shunt, which calls for smooth use of the throttle. This is somewhat exacerbated because there’s quite a bit of pitch once the turbo comes on song and the tyres claw at the surface; the reverse is true under braking. So smooth inputs are your friend, especially on a rain-soaked day.

The gearchange is not to be hurried, but from around 3000rpm the turbo is boosting and the engine is singing its delightful, offbeat thrum. From here, the big Quattro really piles on the speed and it takes time to build confidence in the chassis and understand just how much of that speed you can then carry through corners.

The answer is quite a lot, as it happens. There’s a noticeable amount of lean but the Toyos grip enthusiastically and as you work the throttle mid-corner, through the tips of your fingers and seat of your pants you feel the hardware below start to work its magic.

Around the fast Madgwick and later Lavant, you can play with the throttle and feel power being directed from the front wheels to the back as the car tries to find grip. It’s an interesting exercise and the more you tune in, the more you come to trust that it will keep clinging on and you can keep the throttle buried from the apex to the exit.

Stable and planted, it tells you what it’s going to do and by the end of my runs in the car, I can picture this thing mixing it with contemporary Porsche 944s, and each car’s different abilities making for good racing.

The Quattro was developed for motorsport and it’s intriguing to find one being used for circuit racing. Owen says he has enjoyed campaigning such an unlikely car, and with six meetings in 2022, including drivers’ favourites such as Brands Hatch and Cadwell Park, as well as glamorous destinations like Silverstone, it is a manageable championship.

If the Quattro has got you thinking, then consider that within the six classes, other interesting and eligible cars for the HSCC’s ‘80s Sports & GTs series include the Alfa GTV6, BMW Z1, Jaguar XJS, Mazda RX-7, Porsche 928 and many more. Or, if it’s a Quattro you’re after, Owen is selling his car…

1974 Alfa Romeo 1600 GT Junior – HSCC 70s Road Sports

Alex Childs was racing a Lancia Fulvia Zagato 1600 in the ‘70s Road Sports series, and over four seasons his best result was second in the championship. “That was fun but I thought to myself, ‘I’ve got to try rear-wheel drive’”. As luck would have it, a friend racing this 1974 GT Junior in the same championship decided it was time for a change, so in 2010 the Alfa fell into Childs’ hands.

The HSCC’s 70s Road Sports allows for cars from 1970 to the end of the ’79, with six classes, plus an invitational class, and looking back at past winners of the championship, there’s no shortage of variety taking home the title. From a Lotus 7 to Elan, Lancia Beta Coupe to Datsun 240Z, Triumph GT6 to TVR Tuscan, it’s plenty varied, and the grids are healthy.

“The people make it,” says Childs. “It was the variety of cars and the people that appealed to me; the people made it so friendly and welcoming, and were so helpful if you had a problem with your car. It just made it fun.” Some will even drive their competition car to the circuit, race, and drive home again.

After a six-year absence, Childs, an estate agent by profession, is back for 2022, still using the same trailer that his grandfather had built in the ‘60s to tow his… wait for it… Maserati 250F.

You can trace the 105 series Alfa Romeo back to 1963, and the launch of the Giulia Sprint GT. Child’s GT 1600 Junior came relatively late in the model line’s timeline, joining the range in 1972 and replacing the 1300 Junior in the UK. Even if you have no burning desire to own an Alfa Romeo once in your lifetime, it would be churlish to deny this is a lip-bitingly good looking car. The work of Giorgetto Giugiaro, while with Bertone, you could sell this new today with a battery pack and the chances are people would fall for its charms all over again.

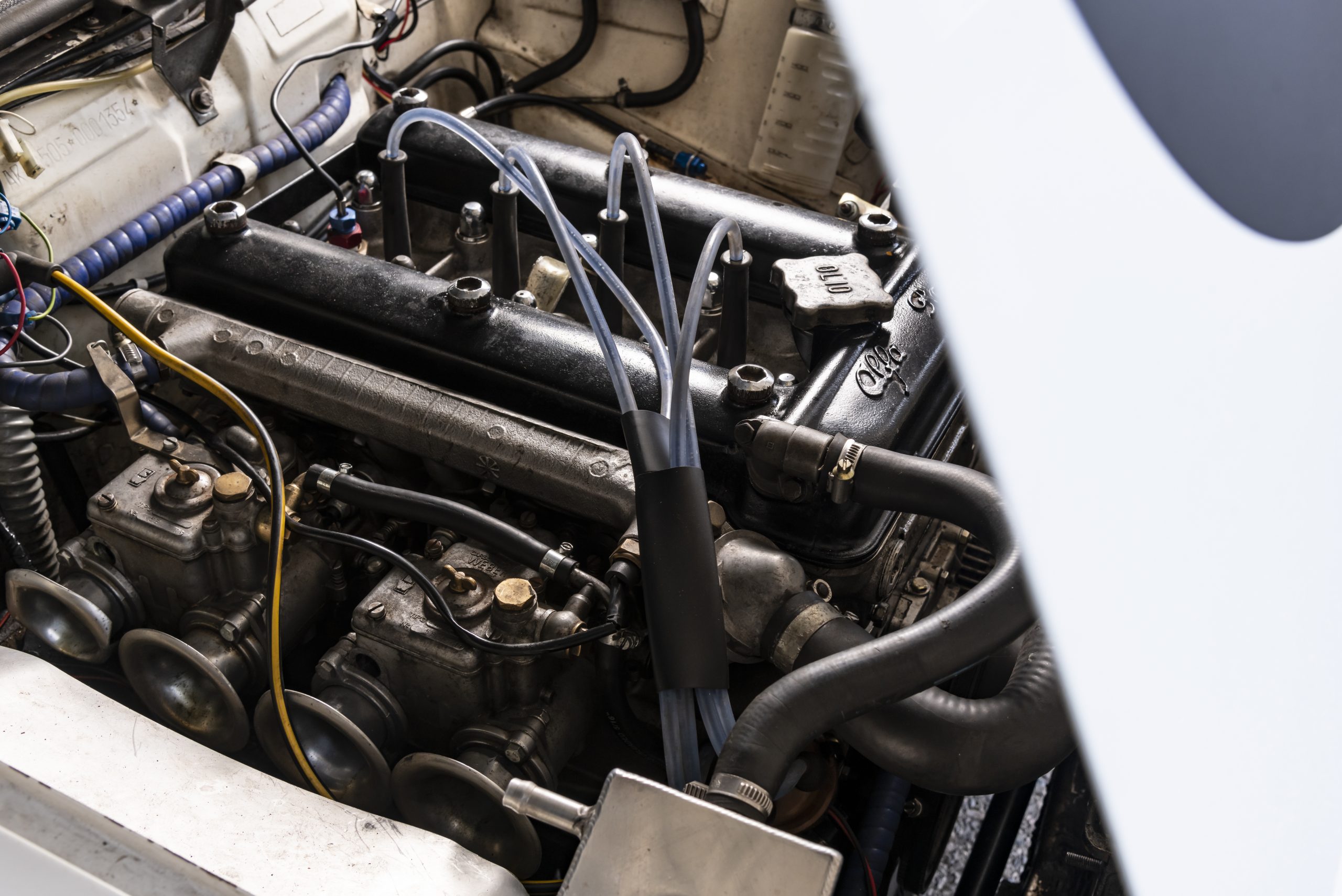

To do so, however, you be a great shame, because that would mean missing out on the aluminium, twin-carb four-cylinder engine which is sweet, willing and laughably characterful after the modern-age Quattro. This 1600cc engine has high-lift cams, a lightened flywheel and racing pistons, and Childs says it will go for two seasons between rebuilds – unless he happens to buzz a gear and put a piston through the side of the block, as he once did at Snetterton…

You know from just looking at the car how well it’s going to handle, with a light engine up front, rear-wheel drive and petite body that packages everything as low to the ground as possible. To make it race-friendly, there’s a single Sparco seat, Sparco steering wheel, sports pedals, Rollcentre Racing cage, additions for a rain light switch and demister and wipers and fan, plus battery isolator and fire extinguisher. Along the way, Stack instruments for the rev counter, water temperature and oil pressure have been added, making the original items stamped with the Alfa Romeo crest redundant.

Like the Quattro, this is by no means a pampered, concours car – it’s a racing car, after all. Yet the period, dainty door furniture remains, and you even use the original key, but because the rest of the cabin has been stripped of seats and carpet, Childs has to use lead ballast to bring it back to the car’s original quoted kerbweight to conform to regulations.

It’s running a Yokohama A021R wet treaded tyre and there’s plenty of water on the circuit when I first venture out. Goodwood’s combination of fast corners, slightly incontinent old cars and wet weather would make for a few underwear-changing moments, were it not for the innate balance of the Alfa’s chassis and quick responses from the steering.

Soon the car is doing a quick step between grip and slip, the tail edging around playfully and able to be held at just enough of an angle so that you don’t have to back out of the throttle, especially through Lavant. Coming out the chicane the tail steps out as much as you wish, and from the pitwall I see Childs’ leaning out and waving his arms in encouragement.

Apparently, in the dry, Childs rarely uses the brakes, preferring to rely on the car’s driftability and maintain as much momentum as possible as he seeks any advantage over heavier but larger engine 2-litre models.

I don’t want to hand the car back to its owner. It moves with the precision and poise of a ballerina and I would happily spend all day working out how to find that sweetest of sweet spots as you chip away at lap times. But Childs is here to have some fun too, so somewhat reluctantly I head back for the paddock and return the Alfa to its keeper.

While we’re not going to pretend that motor racing can ever be cheap, this is as affordable as it could get – especially if you already have a classic in the garage and want to scratch that itch. Owen and Childs can’t recommend racing your classic enough, and by the end of the day Childs and I are hatching a plan to do the Spa 6 Hour race together. I’m still interested, Alex, if you haven’t lost my number…

With thanks to Tom Owen and Alex Childs, the cars’ generous owners.

So you want to go racing?

Got a car and want to race it? Great. But first you will have to wade through the paperwork. First, buy a Motorsport UK Racing Starter Pack (ARDS), which at the time of writing costs £99, then take and pass(!) the driving test that permits you to hold a racing licence. That’s known as an ARDS test, (Association of Racing Driver Schools), and we found that costs start from about £270.

Pass that and you’re officially able to go racing, but that’s before you’ve bought a car and adapted it to meet racing regulations, shelled out on all the eligible protective clothing and helmet – brace yourself for a minimum hit of £1300, including a HANS safety device – and paid to join a championship, plus entry fees for each race, fuel, tyres and other consumables, etc.

There are various championship organisers too. In addition to HSCC, explore Motor Racing Legends, BARC, BRSCC and Masters Historic Racing.

Like other specialist insurers, Hagerty offers cover for motor racing vehicles in storage, in transport and even in the heat of competition on the track, as well as liability cover. Click here to find out more about Hagerty Motorsports insurance.

Read more

Trial by mud: A beginner tackles the VSCC Herefordshire Trial

“It was my birthday, I had a few beers… and I bought an F1 car”

Line up behind me, son, and watch how it’s done! Learning the course at Shelsley Walsh

Seeing your interesting report on 70’s road sports has made me respond. It would be great if you could offer car insurance for road use of classic race cars that included car recovery breakdown. I used to insure my car with you based on the assumtion that my road driven car would be recovered. However your latest ruling was that if the car was used for racing then the recovery would be suspended whether or not the failure was due to racing. Sponsoring the HSCC 70’s roadsports series with a commitment to recover road insured vehicles would be a great advertisement for you and the series. It would also encourage more genuine grass roots racers into the series and underpin the ethos of racing road legal cars.

Thanks for the feedback, Adam. A great deal has changed, it would seem, since you last looked into this matter with Hagerty. Please see the latest motorsport products via this link, and let me know if you have any further questions or if you’d like one of the team to contact you. https://www.hagerty.co.uk/insurance/motorsports/

Oh, and glad to hear there’s another fan of the ’70s Roadsports Championship out there.

I would absolutely love to circuit race my Alfa GTAm rep , or any car for that matter . However the necessary changes to meet race specs and the risk of contact with others , means I simply cannot risk the fact it could be written off , or at least beyond my abilty to pay for repairs . So it’s sprints or hillclimbs for me sadly .