Jesse Crosse started as a motoring hack in 1982, was launch editor of Performance Car magazine and signed up an unheard writer called Jeremy Clarkson. He now writes about automotive technology, and spends his time restoring a pair of fast Fords, a 1968 GT390 Mustang fastback, and the same Ford Sierra Cosworth long-term test car he ran while editor of Performance Car. Here he shares tech tips for the have-a-go DIY car enthusiast.

If it isn’t already, at least one torque wrench should be one of your favourite tools. Why? Because tightening a nut, bolt or machine screw to the torque specified for the job it was engineered to do is not only the best way, it can also save you from future grief. Nasties that can be caused by tightening to the incorrect torque include fluid leaks (especially oil) breakages, cracked castings, gas leaks, mixing of oil, water and combustion products, distorted or warped components, snapped bolts and even wheels falling off. While some of those might sound extreme, they’re all possible and some are very common. Over or under-tightening, or tightening critical things like cylinder head nuts or bolts in the wrong order can be catastrophic.

Pre-internet, most car and motorcycle DIYers were limited to whatever information on torque settings was published in a Haynes manual, or in some cases, re-printed factory workshop manuals. Some of the sources tended to stick to basic areas like cylinder heads, connecting rods or main bearings, but didn’t necessarily provide torque settings for the many less crucial parts like rocker covers or sump bolts. All of these are important and today, it’s much easier to find more information on a greater number of components on a much wider range of cars through the thousands of sources and groups online. It’s easier too, to cross check a source and make sure it’s correct.

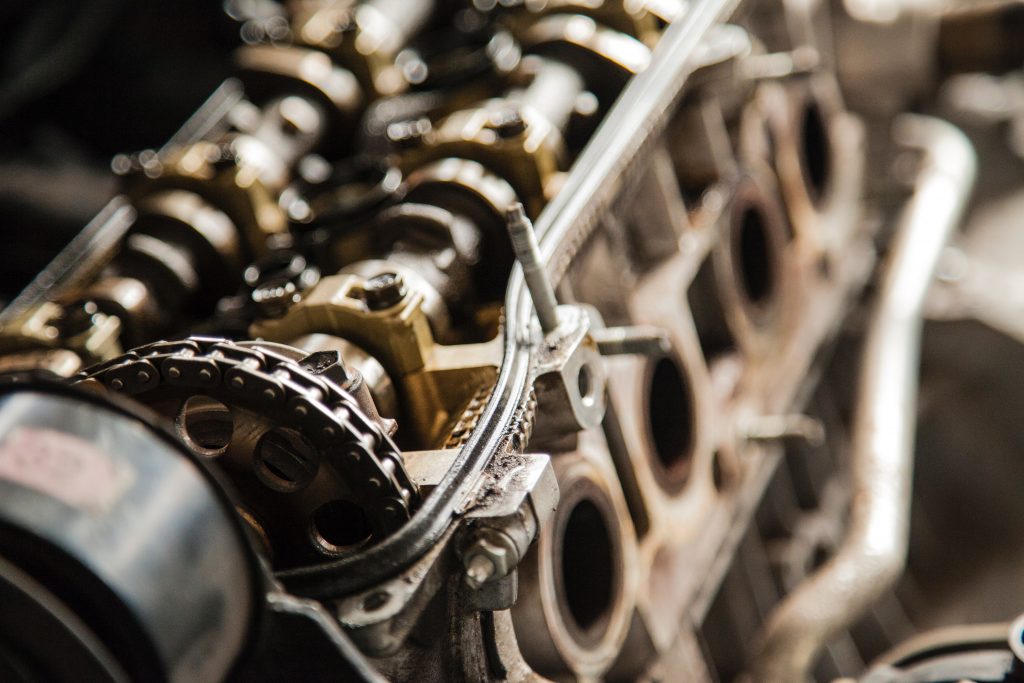

On some components, like cylinder heads again, use of a torque wrench isn’t optional. Failing to use one following the tightening sequence given in the manual will at best lead to a leaking head gasket and at worst a damaged cylinder head.

Torque wrenches take standard sockets and work in a couple of different ways. The first type has an internal mechanism and the required torque, marked in lb ft, (pounds feet) Nm (Newton metres) or occasionally Kg m (kilogram metres), can be set on a scale. Once the set torque is reached, the wrench will ‘break’, with a click. The second cheaper and less accurate type has a quadrant scale and needle on the top side. As you apply torque, the wrench deflects slightly and the needle indicates the torque on the scale.

The third method often specified on more modern cars, is to tighten the nut or bolt to a certain angle using an angular torque gauge. This resembles a glorified socket but with a circular, 360° scale on its face. As you tighten using a conventional lever bar from the socket set, the disc scale section of the gauge is held in the same position against the job, using a steady. As the nut or bolt is tightened, the angle of rotation is shown on the scale. A workshop manual might specify for example, that head bolts are tightened to a certain torque using a conventional torque wrench, then further tightened to an angle of 90°.

Torque wrenches come in various sizes to cover certain ranges. Smaller ones covering the lower torque range, say 12Nm to 60Nm, are correspondingly smaller and shorter in length to reflect the amount of leverage required. Those covering the larger ranges, say up to 300Nm, will be much longer like a large breaker bar, to reflect the large amount of effort required to apply that much torque.

Ultimately, tightening to a certain torque is intended to produce a certain clamping force, whether it be a cylinder head bolt or wheel nut and that can be significantly affected by the amount of friction between the mating surfaces of the nut or bolt head and the surface it’s tightening on to. So if friction is high, some of the applied torque will be wasted overcoming it and the clamping force produced will be reduced. For that reason, specialised high performance bolts, (ARP head bolts, studs or connecting rod or main bearing cap bolts) are supplied with a special grease to apply between the head of a bolt or nut and the clamping surface and on the threads, before tightening. The use of angular torque gauges where called for is a way of avoiding that because whatever the friction, the tension applied to the bolt will be the same.

A manual may or may not specify that head bolts, for example, should be tightened in stages as well as a certain sequence. So tighten all the bolts in sequence to half the final amount, then all to the final amount. It’s important to follow instructions like that exactly. In general, when torquing sequences of bolts or even tightening manually with a spanner, it’s always important to do it in stages to avoid distortion, leaks or cracking. So a set of two or three torque wrenches is an invaluable addition to the workshop and you might be surprised how many things on the car or motorcycle you can find torque settings for.

Read more

Socket Set: A beginner’s guide to changing brake fluid

Socket Set: Maintaining your car’s ignition system

Reviewed and Rated: The best OBD readers and scanners in 2021

That Teng tools wrench is not digital. Well it is, but not the so far as digital often implies electronic.