Jesse Crosse started as a motoring hack in 1982, was launch editor of Performance Car magazine and signed up an unheard writer called Jeremy Clarkson. He now writes about automotive technology, and spends his time restoring a pair of fast Fords, a 1968 GT390 Mustang fastback, and the same Ford Sierra Cosworth long-term test car he ran while editor of Performance Car. Here he shares tech tips for the have-a-go DIY car enthusiast.

It’s that time of year isn’t it? The time of year when your car has been sitting in the freezing cold all night, you hop in and twist the key to be greeted by flickering instrument lights and the forlorn click of doom. A duff battery is one of the most common things breakdown services are called out to, probably because batteries are so easy to ignore until they fail.

Although it’s easy enough to get an idea using a multimeter (more of that in a minute) I’ve found it’s pretty obvious to tell when a battery is on its last legs without the need for any tools at all. When I buy a second hand car I assume the battery is on the way out until proven otherwise and the acid test (no pun intended) is usually when the first chilly morning arrives and you turn that key.

It’s a bit like one of those ‘world’s strongest man’ competitions where the guy has just lifted close to half a tonne but when another kilo is added, it’s too much.

It’s much the same for the battery. It might be able to cope in milder temperatures but once freezing, with its strength sapped and thick engine and gearbox oil making the starter motor’s job harder, it struggles to do the job. If I crank the engine and it sounds sluggish, I take that as a warning that the end is nigh. I’m assuming at that point the alternator is charging (if it wasn’t then the battery would go flat whatever the weather) and the battery terminals are in good shape.

I like to clean the terminals on both the battery and the battery leads with a bit of wet and dry so they’re nice and shiny, then smear a light coating of Vaseline on them to prevent oxidation build-up, before clamping them up. Once charged and left for a few hours, a multimeter across the positive and negative terminals should read between 12.6 and 12.8 volts without the engine running, if it drops below 12.6 volts, then all is not well.

There is one other possibility and that is that the battery cells are sulphated, a battery sickness where sulphate crystals build-up on the battery cells due to lack of use, over or under charging. If the battery isn’t too far gone, using a good trickle charger with a reconditioning cycle can bring it back to life. I owned a Nissan Skyline R34 once, still fitted with the original small factory-spec battery. It kept going flat despite charging and – convinced it was knackered – I made a last-ditch attempt to save it by trying the reconditioning cycle on my trickle charger. To my amazement that did the trick, restoring the tiny battery to full health, but I haven’t always been so lucky.

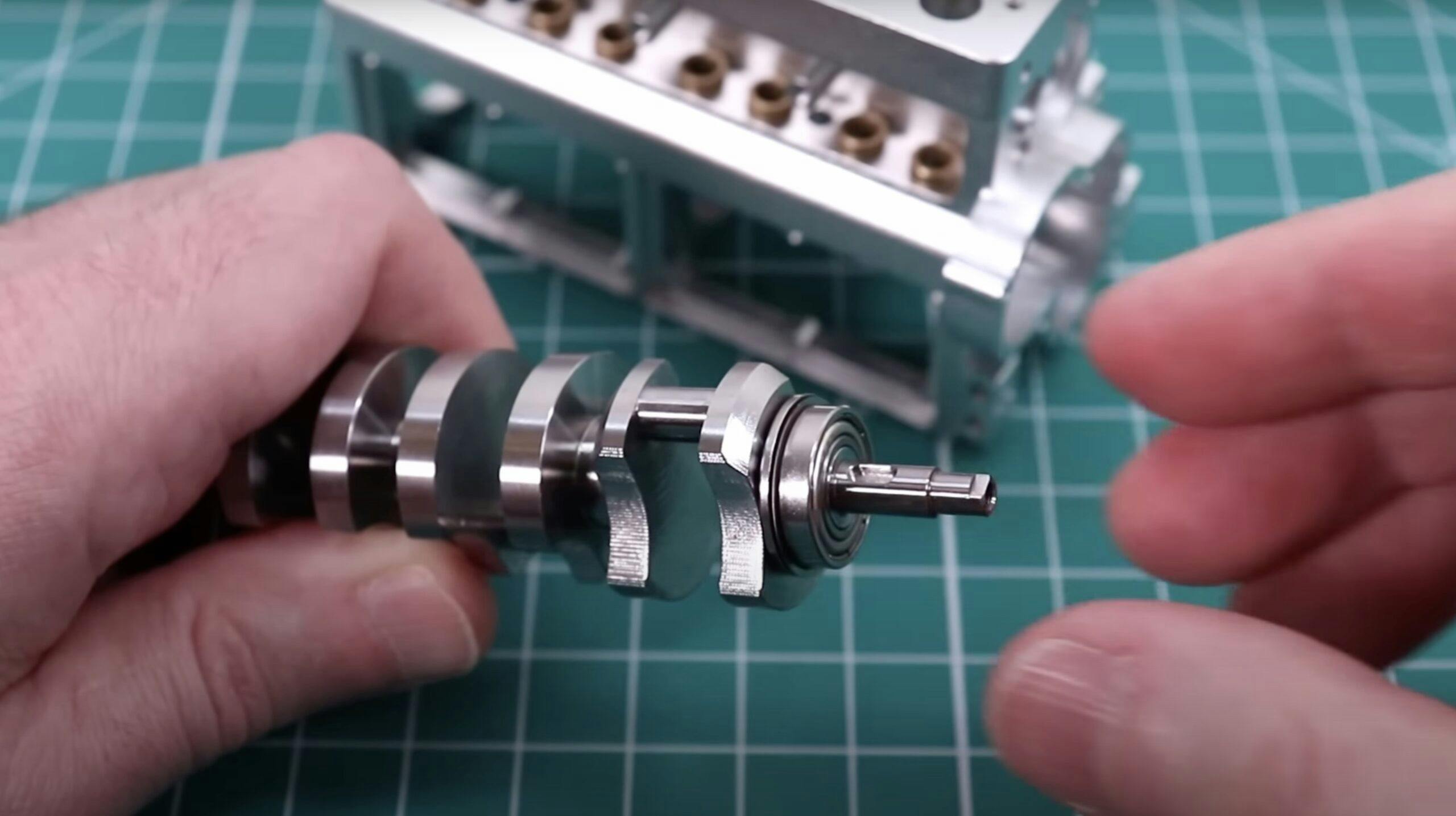

Batteries don’t last forever and if they’re more than a few years old, and especially if they’ve been standing around a lot, they’re likely to be heading for retirement. Contrary to popular belief, normal use, such as powering the headlights, is not something which ages a battery especially. A battery manufacturer once explained to me that a bigger culprit is mechanical vibration which eventually fatigues battery cells to the point that they short circuit and fail. The internals of modern batteries are designed with vibration resistant technology for that reason. A battery’s relationship with the car is more about supply and demand. The battery feeds the car’s electrical systems and if everything is well maintained, working properly and there are no extra ancillaries exceeding the alternator’s output (like massive spotlights), there shouldn’t be any problems.

If all else fails, changing the battery is usually straightforward on any classic as they’re generally accessible either in the boot or engine bay. Finding the correct battery is easy enough these days the thanks to the lookup facility on supplier websites, although on earlier classics, it will be necessary to do some research. When the time comes to make the swap, a modern classic may need a radio code to reactivate the radio after the old battery has been disconnected.

To make the change, disconnect the negative terminal followed by the positive terminal, undo the battery clamp (try not to drop any nuts or washers, and put them somewhere safe) and lift the old battery out. Fitting the new battery is the reverse procedure and even on new battery I’ll lightly clean the terminals and smear on some Vaseline to keep them free of corrosion. Tighten the battery clamp carefully, enough to stop the battery moving when driving and all should be well for another few seasons.

All good stuff although as petroleum jelly (Vaseline) is an electric insulator it’s best kept outside the metal to metal connection to avoid oxidation! The best investment for older classic cars not being driven is a battery isolator switch to avoid the leakage in a car’s electrical system even when the ignition is off. Some like Aston’s had them fitted as standard.

Disconnect the earth terminal first – it’s not always the negative terminal.

Some quite elderly cars have the radio and perhaps other accessories protected by a digital code, which may be lost when the battery is disconnected, so check and make a note of any and you will be able to re-enter them when the new or re-charged battery is connected.

Recommend the use of a battery conditioner rather than a battery charger. When the car is not in use for a long period use a battery conditioner that will keep the battery at its optimum performance level without overcharging. The two models I know of are called CTEK and Accumate. I use the former that cost about £75.