Just over a decade ago the government propped up the motor industry with a scheme which saw registrations of new cars leap by 28 per cent in the midst of a recession. Now, in the wake of the Covid crisis there are calls to bring back a similar incentive, called scrappage, to get the nation’s motorists and businesses spending again.

To many in the classic car scene, the scrappage scheme appeared to have a disastrous downside. At the time, there was widespread talk of cars being destroyed in the name of securing a discount on a new Korean hatchback. Mike Brewer, Mr Wheeler Dealer to his fans, told Hagerty how he remembers weeping over the loss of precious, enthusiast cars that were in no way fit for the crusher.

But what’s the truth? Was it really a disaster for fans of classic and modern-classic cars? And is it something we should encourage to help the motor industry get off its knees and continue to reduce emissions? Or are there painful lessons to be learned from? Hagerty speaks with those on both sides of the fence and discovers just how divisive scrappage was – and could prove to be again, should it return without fresh thinking.

What is scrappage and how did it work?

Scrappage gives financial incentives for a driver to trade in and scrap an old car in exchange for a brand-new model. Such a scheme was introduced to the UK in May 2009.

Under the rules for the last incentive, a buyer could trade in a car which was more than 10-years old and receive £2,000 off the price of a brand new car. To prevent people simply buying a £100 banger just to secure the trade in value, they had to have owned it for more than 12 months and it had to have a valid MoT.

Once the paperwork was filled in and the process completed, the government contributed £1,000 and the other half of the bonus was funded by the vehicle manufacturer.

Why was it introduced and could it come back?

Scrappage was introduced to keep the motor industry afloat in the face of dire financial straits where banks were reluctant to lend and consumers didn’t want to spend savings.

Paul Everitt was the chairman of The Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders at the time and explains: “Month after month car registrations were going down. The news talked of an impending financial collapse, and no-one knew where the bottom was.”

The UK car industry pointed to the successful scrappage schemes in Germany, France and Italy and put a case for how it could work here in the UK. The government at the time was persuaded and the scheme was born.

Today the industry is applying similar pressure to support businesses following the Covid Crisis, with motor industry leaders arguing that a scrappage scheme could be used to help remove polluting cars from the road and replace them with low emission and electric cars.

What effect did the 2009 scheme have?

It was dramatic. In total, 392,227 cars were registered through the scheme and customers were literally fighting over cars at some showrooms. But the most popular models were budget small cars, especially those from the Korean brands such as Hyundai. The i10 city car cost £4,995 after scrappage – or just £85 per month on finance.

Michael Nobes runs a chain of Hyundai dealers on the South coast, and tells Hagerty: “I’ve never experienced anything like it. I had customers queueing from one end of the showroom to the other.”

Needless to say, the sales success of new models also meant the same number of old cars were consigned to the scrap heap – including some cars which were considered either classic, exotic or simply rare at the time. Looking back at the list a decade later there are many cars which are now rare and sought-after too.

What happened to the scrapped cars?

Once the paperwork had been completed, the cars were officially destroyed and could not be returned to the road or exported. The government made sure that no one could cheat the system and without the proper paperwork the dealer wouldn’t get any money. “We had some lovely cars that were scrapped,” said Michael Nobes. “It was the law though. There was no way it could be bent so those cars could survive.” And Nokes makes a point that echoed across the industry at the time, which was doing all it could to keep up with demand: “We didn’t have the time to pause and consider if a car was worth saving.”

What sort of cars were destroyed?

Unsurprisingly the most scrapped cars were best-selling models from a decade or more previously. Even now there will be few people mourning Austin Maestros, Ford Fiestas and Nissan Micras, everyday cars that Hagerty and many drivers celebrate, at the Festival of the Unexceptional.

That’s bad enough. But in among the government’s official reporting on the Vehicle Scrappage Scheme (VSS) the data highlights some truly rare and sought-after classic and modern-classic cars which will make painful reading for any car enthusiast.

German exotica meeting the crusher included an Alpina B7, BMW’s M5 and 850i, three Porsche 928s and even an original Audi Quattro. A total of 31 Peugeot 205 GTIs died, alongside 14 Impreza Turbos and several V12 Jaguars.

Less sporty but still sought-after now is a long list of Series Land Rovers, Morris Minors, classic Minis, original Beetles, 2CVs and MGs.

It seems inconceivable now that these would be swapped for a discount on a city car. But Tony Whitehorn, who was managing director of Hyundai at the time, explained: “A lot of these cars weren’t that interesting a decade ago and many were on their last legs with the owners facing huge repair bills. The owners’ clubs moaned but when you asked them to come up with £2,000 to save a rotten car with a troublesome engine they all shrank back into their forums.”

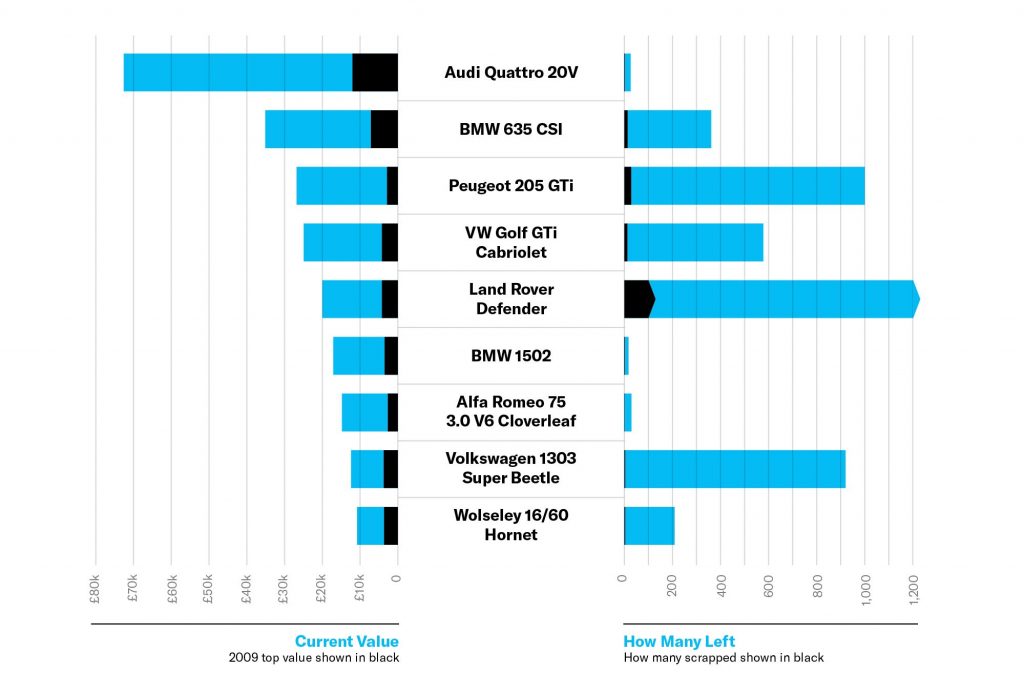

At a glance: classic cars lost to the crusher during 2009’s scrappage scheme

Couldn’t these cars be used for parts, at least?

Yes, they could, and some canny scrap dealers stripped some of the more interesting cars for parts. Only the bodyshell couldn’t be reused. Some savvy owners, who had taken time to study the small print of the VSS, also stripped their trade-in down to the bare bones before rolling it into a dealership.

Such an approach could have increased the volume of used components available to classic car owners. This in turn would have helped protect the classic car industry, which contributes a significant £5.5bn to the UK’s economy (see below). Unfortunately, few drivers knew the regulations inside out, and even those that did weren’t inclined to take their old car apart.

Ultimately, many cherished models were crushed without being broken for parts, as the sheer number of vehicles arriving at yards was overwhelming. YouTube videos from the time show plenty of interesting cars being lifted off trucks by cranes and thrown straight into a baler.

What is the scale of the classic car industry?

The scale of the classic car industry should not be underestimated. According to the Federation of British Historic Vehicle Clubs (FBHVC), more than 35,000 people are employed directly by the industry and it contributes £5.5bn annually to the UK economy.

However, that data is based on a 2016 survey. Last year, the FBHVC carried out a National Cost of Ownership Survey, which revealed that the number of historic vehicles registered with the DVLA has risen to nearly 1,242,000 vehicles, and each owner spends an average of £1,489 a year maintaining their classic car.

It adds that nearly 10m people are interested in historic vehicles, and 21m view them as an important element of the UK’s heritage.

Could scrappage happen again?

It already is, albeit on a smaller scale in London. Since October 2019 Transport for London has offered incentives of up to £7,000 for low income families and businesses to scrap older cars, vans or motorbikes and replace them with new low-emission cars. But there is growing pressure to widen the scope and make it nationwide.

There were strong rumours in May that a new scrappage scheme was close to being announced, with the government ready to swap older cars for a £6,000 discount on a new electric or hybrid model. Similar schemes have been introduced in France and Germany and this has seen demand recover to pre-Covid levels. But the government here has been wary of introducing it. Some say this is over concerns that scrapping serviceable old cars is not environmentally sound as it takes a great deal of energy to build new vehicles – around one fifth of the lifetime CO2 pollution created by a petrol car is created when it is made according to the European Environmental Agency.

However, the automotive industry continues to call on government to introduce a new version of scrappage or equivalent incentive. Mike Hawes, SMMT Chief Executive said: “Of Europe’s five biggest economies, Britain now stands alone in failing to provide any dedicated support for its automotive industry. Until critical industries such as automotive recover, the UK economic recovery will be stuck in low gear.”

There is also evidence that some car buyers have been holding off making a purchase in case they miss out on incentives. What Car? magazine polled 6,000 potential car buyers in early July and reported that a third were waiting for scrappage or some other incentive to be introduced before ordering a new car.

What does the classic car community think?

Generally, it is horrified at the thought of it. In 2016, 33,765 people signed a petition to save some surviving cars which were stored on an old airfield. It was rejected by the government as the cars were now privately owned by the scrap dealers and could not be rescued by politicians.

Mike Brewer, host of Wheeler Dealers, is the most famous classic car fan in the world, with 200 million viewers in 217 countries watching his TV show. Speaking with Hagerty, he shared how affected he was by the loss of an MG: “I wept during the first scrappage scheme. My local Citroen dealer had a 6,000 mile MG Metro. It looked like someone had just peeled the cellophane off it – and it was being scrapped. That broke my heart. I could see why the scheme was there to keep the industry going but there were profits to be had by offering people the opportunity to buy them.

“If scrappage is coming back, I will do a personal plea to everyone out there who’s got a car like that MG and is thinking that they might scrap it in exchange for two grand to contact me first!”.

Adam Sloman, General Manager of the MG Car Club said: “The scheme hit some really rare MGs from the 80s quite badly – the likes of the MG Metro, Maestro and Montego are now genuinely an endangered species. There were also horror stories of extremely rare cars being chopped in by people who had no idea what they were scrapping and everything was seemingly accepted by the scheme, regardless of condition or rarity. It would be a genuine tragedy if it came again as it had such a dear cost to the classic and modern classic scene.”

What effect did it have on the classic car market?

With nearly 400,000 cars destroyed which were more than a decade old in 2009, it took out an entire generation which would now be 20-30 year old classics. “It certainly drove up prices of those classic cars which were left behind,” said Brewer. “We are still seeing the effects today. Values have been rising at 15% a year pretty consistently ever since. We are now at a point where we see Ford Sierra Cosworths being sold at auction for £155,000. That’s great if you own of those but there is all this value in cars which have been left on an airfield to rot or were recycled into bean cans. That’s not great for anyone.”

Is there a way to protect classics?

There is. Some makers such as Ford and Vauxhall introduced their own ‘scrappage’ schemes as sales incentives without government financial help and promised to allow dealers to divert classics – including their own past models which have become sought-after, like the Ford Mondeo – away from the scrapyard so they could be saved. The government could introduce a filter which flags up interesting models which are over 30-years old and gives groups such as accredited owners’ clubs the chance to assess them. This is likely to be too difficult to administer however and would not fit in with the so-called ‘green’ positioning of any scheme, even if there are question marks over the environmental impact of the continued production of millions of new cars.

Mike Brewer has an idea though: “Maybe there is a way that it could work. The government could give the dealer 14 days after the car comes in to refund the £2,000 if they think they can sell it on. If they can dispose of the car for a profit, it’s brilliant for everyone and the good cars aren’t wasted.”

What measures should be put in place is scrappage were to return? Have your say in the comments, below.

Everything you need to know about using E10 fuel with your classic car

Hi Tom, we have another solution – instead of scrapping, incentivise conversion to EVs. We have a plan at Electrogenic.

Would love to do an article for you to explain more.

All the best, Steve

Whilst scrappage May have permitted a select few Manufacturers to thrive, sadly it came at the expense of far too many “every day drivers” which now are almost so scarce that they are rarely seen on the roads.

Worse though is the damage to the public image that was created.

Today, there are better options, convert to more up to date engines which are better suited to today’s emissions limits. Or better still, create a whole new retro manufacturing industry of buying back cars to convert to either Hybrid, or totally electric. The Technology is there to do this already

A big benefit to those who invest in classic cars simply as investments as scarcity drives up prices! But scarcity and investment cars don’t supply jobs for all those who work in the classic cars industries.

The biggest problem with the Scrappage Scheme is we’d be taking British cars out of the market in favour of imports. Let’s be totally honest, how many “bread and butter” cars do we make in the U.K.? Not that many…..!

We’re a new scrappage scheme to be introduced now all that would happen is that taxpayers money would flow out of the country to the hordes of foreign car makers. Small garages would be damaged as they would be cut out of servicing older cars with main dealers servicing the new tech loaded new cars. This, quite apart from the plasmid perfectly good useable cars and nobody ever mentions all the co2 involved in making new cars and transporting them across the world to their new owners.

According to the International Council on Clean Transportation, the lessons learned from scrappage schemes across Europe introduced after the last crisis was that these schemes made almost no difference to real-world GHG emissions. Only replacing older diesel vehicles with Battery EVs might make any real impact. Surprisingly, it suggests that real-world GHG emissions have stayed relatively stable for average cars over the period 1990-2020 despite official CO2 levels dropping. See: https://theicct.org/publications/vehicle-replacement-programs-covid-19-may2020 .

I also agree with Barrie that it is expensive for taxpayers and would result in a wave of imported cars. With the exception of the Nissan Leaf which is a relatively affordable BEV made in Sunderland, the next British low-carbon recipient is the Jaguar I-Pace starting at £60,000! Oh, and it is made in Austria.

Better to continue with current schemes to incentivise switching to BEVs such as grants to help offset the higher costs of battery cars, zero percent benefit-in-kind for company car drivers and spend the money saved from not introducing a scrappage scheme on continuing to improve the public charging infrastructure.

We’re being manoeuvered into thinking on a false foundation, as if CO2 is a problem. Current CO2 levels in the atmosphere (0.04%) are at lower levels than many times in history, including thousands of years ago. I smell a rat.

Scrappage schemes are terrible for people on a low budget who can only afford cheap old bangers. Even £6k off a £20k+ car isn’t much, so the people trading in will be those who can afford to look after their cars. You then lose the 1 owner FSH older cars to the crusher and the result is a bottom end of the market full of overpriced, poor quality cars that are a pile of breakdowns waiting to happen. We already see this as a result of the 2009 scheme. If it happens again it will probably price most low earners out of car ownership.