We British like making machines. Ever since a bright chap in a top hat started making steam engines at the start of the industrial revolution, we’ve been beavering away with our lathes and Vernier callipers. And often, the things we make are pretty good. But what are the five best British machines of all time? Here’s my (very subjective) list. I hope you enjoy them!

Number 5: The Challenger 2 Main Battle Tank

There are some things that the British do well. Ask anyone around the world, and they will probably say that we’re known for our F1 engineering, costume dramas and tea. Which brings me to the Challenger 2 (C2): the world’s only main battle tank fitted with a built-in kettle.

If you are into machines, then you’ll probably think that all tanks are pretty awesome, but the Challenger 2 stands out from the crowd. Not only is it powerful- the Perkins 26 litre V12 takes all 62 tonnes of this beast up to a top speed of nearly 40 mph- but it is also probably the best-protected armoured vehicle in the world. Its Dorchester armour is officially classed as ‘Secret’ by the military, but suffice to say it is pretty good- allegedly twice the strength of steel.

Despite years of combat operations in Bosnia, Kosovo and Iraq, no Challenger 2 has ever been lost to enemy fire. In Iraq, one lost a track and was stranded right in front of an enemy position. The crew, unable to move, could only radio for support as a fusillade of enemy fire rained down on them. The tank was hit by 14 rocket propelled grenades and a Milan missile, at the time one of the best anti- tank missiles in the world. When the tank was finally recovered, the crew found that a broken sight unit was the only damage. Six hours later, they were back in action.

So it can take punishment, but a tank is there to deliver it too. The main armament is a 120mm gun, but it also has a couple of machine guns and the ability to make an almost instantaneous smoke screen by dumping diesel onto its exhaust. The main gun is also electronically stabilised, so even when driving across the most arduous terrain, turning, dodging and weaving to avoid enemy fire, the barrel remains resolutely focused on the target. Unlike other nation’s tanks, the Challenger has a rifled barrel, allowing it to fire something called a High Explosive Squash Head (HESH) round, essentially a lump of steel and concrete. This has a range out to 5 miles, and is designed to just knock things over: bunkers, buildings, armoured vehicles, even cars. It does this really well.

So finally, back to the kettle. Everyone knows that tea is absolutely essential to the effective operation of the British Army, and that is why every Challenger is fitted with a Boiling Vessel (‘BV’) which provides a permanent supply of hot beverages. As it should.

Number 4: The Bentley 4 ½ Litre Blower

Last summer I was in the paddock at Le Mans Classic, surrounded by some amazing cars. Porsche 917s rubbed shoulders with the Ferrari 250 ‘bread van’ and the Ford GT40. But what drew the most attention? A huge green car that was once described by Ettore Bugatti as “the world’s fastest lorry” and detested by W.O. Bentley himself who said, “The supercharged 4½ never won a race, [it] suffered a never-ending series of mechanical failures, [and] brought the Bentley marque into disrepute.”

Created by Sir Henry ‘Tim’ Birkin in 1929 to compete for the Le Mans crown, the addition of a supercharger was not endorsed by Bentley. But supported by private money, Birkin pressed ahead anyway, building 55 of them and entering them in various events, with very limited success.

So why did I choose this 1920s 4 ½ litre supercharged beast rather than the E-Type, the DB5 or even the Mini? Because this is a car which makes you run out of superlatives when trying to describe it. Firstly, the sound of this thing trying to start is like a Siren’s call for any petrolhead. There is clanking, banging and scraping as if the 242 horses contained within are clamouring to escape. Then in one almighty instant they burst free, and the engine roars into life like a spitting, angry dragon.

And it looks so, well, British. The traditional Blower shape is of a large, chunky green brick with the supercharger almost absent-mindedly stuck on the front. It is made of proper things: leather, brass and steel. The one at Le Mans last year had a tatty Union Jack emblazoned on the door- just as the car that was James Bond’s original drive should do.

Then there is the way you have to drive it. There’s no synchromesh, almost no grip at the wheels, and brakes that pull you around the road but don’t slow you down. If you are at all weak, tentative or gentle, this car will chew you up and spit you out. You almost have to channel the blustering confidence of Birkin himself to drive it properly, chucking the back end out at every corner and hammering on the brakes to make it stop. But get it right and this is a sublime experience which people- all of them- will stop and stare at. It is quite simply an unfathomably good machine.

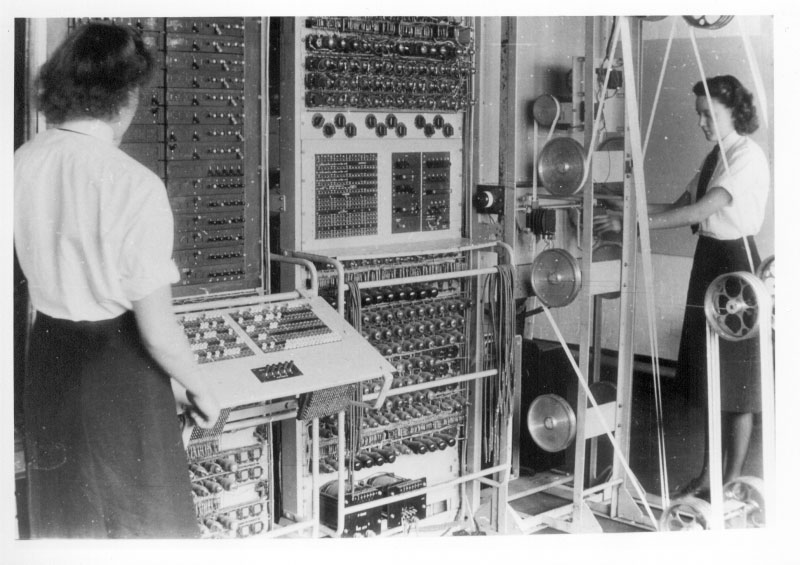

Number 3: Colossus: The World’s First Programmable Electronic, Digital Computer

Recently a great deal of media attention has been focused on codebreaking at Bletchley Park, and in particular the work of Alan Turing. Most people know, for example, that Turing designed the first computer- Colossus – at Bletchley in his quest to break the Enigma code.

Unfortunately, all of this is wrong. Colossus was actually built by Tommy Flowers, a mechanical and electrical engineer from the East End of London who had worked for the GPO before the war designing telephone systems. The first one was built in Dollis Hill, and was designed to crack the Lorenz cypher, a code used by the German High Command that was significantly more complex than Enigma.

Flowers’s machine, using a novel array of vacuum-filled valves, worked perfectly and by the time the Allies launched the D-Day offensive in June 1944, it was routinely cracking encrypted messages giving the home side an advantage that is said to have shortened the war by two years.

In 2007, a working replica of Colossus was unveiled at the National Museum of Computing at Bletchley Park. When tested, this was proved to have a processing speed of 5.8MHz, an astonishing rate for a machine of that age. In comparison, the original Apple Macintosh (introduced over 40 years later) had an 8MHz processor.

The combination of untested, cutting edge technology combined with extremely complex mechanical engineering, created in a wartime environment within incredibly tight timescales make Colossus truly one of the best British machines ever to have been constructed.

Number 2: Thrust SSC

No list such as this would be complete without mention of the first car to officially break the sound barrier. On 15th October 1997, the Thrust SSC was driven at 763 mph by Wing Commander Andy Green, a Royal Air Force pilot and owner of an enormous pair of testicles.

Lots of fuss was made about the Bugatti Veyron because it had over 1,000 bhp. Just to put that in context, Thrust SSC (standing for ‘Supersonic Car’) delivered 110,000 bhp from two Rolls Royce Spey jet engines of the type used in the Phantom fighter aircraft. The other figures are also as mind- bending: it weighed over 10 tonnes, had aluminium wheels, and used 18 litres of fuel every second. Oh, and had a 0-600 speed of 16 seconds. That’s 0-600. Six hundred.

The official land speed record-breaking run took place in the Black Rock Desert, Nevada. In order to officially achieve the record two runs had to take place, each of which was independently recorded by the FIA. They acknowledged that Green had not only achieved the world record for the flying mile (763 mph) and the flying kilometre (760 mph) but had also broken the sound barrier on both runs.

So, where are Green and the Thrust team today? Propping up the bar in their local, telling stories of what it’s like to drive the fastest car on the planet? Of course not. All being well, later this year the new Bloodhound SSC car will take to the South African desert in an attempt to break the 1,000 mph barrier. And who will be behind the wheel? Only one man for the job: Andy Green.

Number 1: The Supermarine Spitfire

A few years ago I was out running when two Spitfires, their wing-tips almost touching, roared low over my head having just taken off from a local aerodrome. These two old machines brought me to an abrupt halt, and I couldn’t help but stand there gawking. I still live close to that airfield and regularly see Spitfires in the skies, but familiarity has not dulled my sense of awe when I see them.

But why should a mere machine, a relatively primitive combination of metal, canvas and rubber, make the hairs on the back of my neck stand up?

The sound of the thing hits you first, generated by 27 superb litres of Rolls Royce V12 power that churns your stomach before it even reaches your ears. At a distance it is unmistakeable, and up close it just seems to sing, a deep baritone rumble that threatens and reassures in equal measure.

Next, the look of the thing is good enough to make a grown Englishman cry. It is hard to believe those swept- forward elliptical wings were designed for aeronautical performance rather than simple aesthetic beauty. The nose, the canopy, the tail plane, all just combine to create something that is as stunning as any work of art.

A major part of the Spitfire’s appeal also comes from its ability to do its job really well. A few years ago I was lucky enough to exchange correspondence with Geoffrey Wellum, a Battle of Britain pilot whose superb First Light is one of my favourite books. “When I was first given one to fly, my first emotion was almost intimidation” he wrote. “[The Spitfire] felt like a thoroughbred horse watching a new rider coming up and wondering how much to be bloody minded. But once I was inside, the Spitfire, quite frankly, flew me.”

And, despite the figures showing that the Hurricane actually shot down more German aircraft that the Spitfire during the Battle of Britain, every small boy knows it was the Spit that saved the day. For me, this beautiful, powerful, deadly instrument is the best British machine ever made.