At the 1990 Detroit motor show, there was ice on the roads and snow at the edges of the sidewalks. The temperature was a sharp -5C overnight and as the first of the press and exhibitors waited at an ungodly hour for the doors of Motor City’s Cobo Hall convention centre to be thrown open for breakfast briefings, figures could be seen huddled together, back to the wind and chins nuzzling into scarves.

America’s biggest motor show was about to do its thing. The nation’s powerhouse car makers would flex their muscle, executives would make bullish speeches and designers and engineers would be wheeled out alongside their latest creations to put across a well-rehearsed PR pitch on why their latest new car would shake up the market and excite consumers.

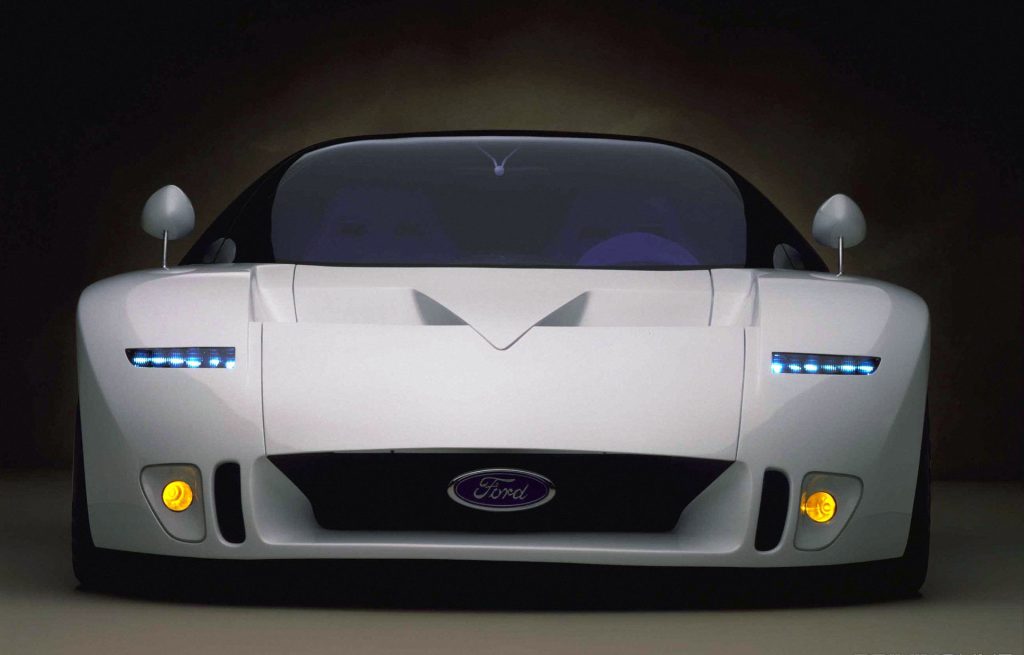

No PR pitch was required for the Ford GT90.

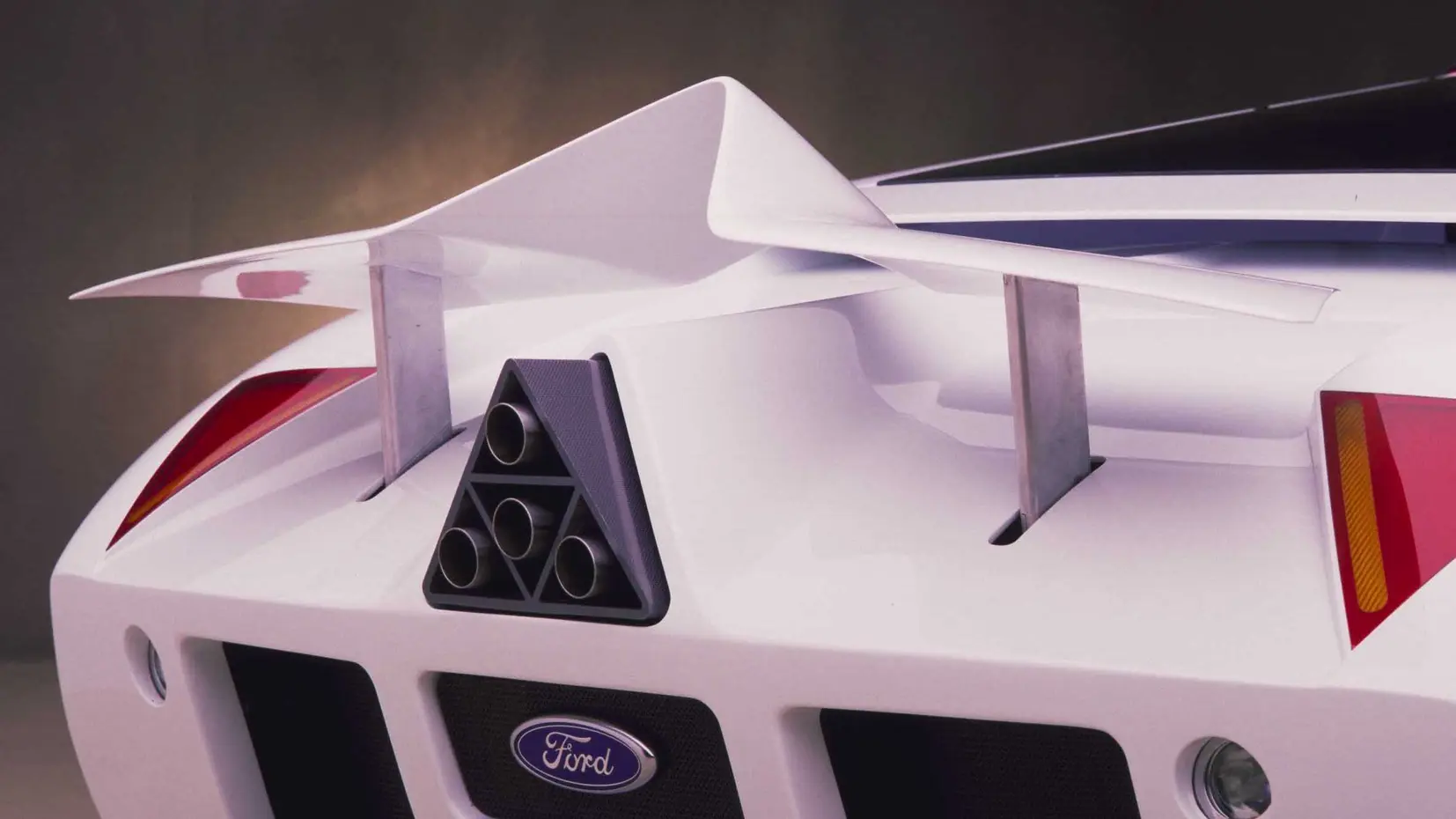

The quad-turbo, V12 concept for world-beating 235mph supercar caused a sensation. At a stroke, Ford would have reporters calling in copy and editors ripping up front covers as they swept everything aside for a big splash on the blue oval’s sensational supercar.

The company hadn’t had a reaction like this since it went to war with Ferrari and revealed the GT40, in 1964. And once again, car enthusiasts couldn’t get enough of it. So why didn’t Ford build its dazzling GT90?

Why Ford needed a new supercar

Ford’s fortunes have roller-coasted over the decades more than most. Its highs and lows inevitably track the success and failure of whatever were the key money-making cars of the time. Get it right, and Europe and (latterly) China, prop up the North American side, and vice-versa.

By the early ’90s the company design was at a low point – in every market. Thankfully for Ford, its competitors were producing similarly bland jelly-bean cars that often looked so indistinguishable that owners could barely tell which was their car on a dark night in a Sainsbury’s car park. The US market Escort was a personality-free reskin of the Mazda 323, while the European Escort was ripped to shreds by critics, who accused Ford of essentially treating its customers as too dumb to notice such a phoned-in product.

And few drivers bought a Ford for the way it looked in the mid-’90s. Still some years away from bright sparks like the Ka and Puma, Ford design was viewed as being rudderless by critics on both sides of the Atlantic. To compound the image problem, Japanese car makers were gaining a foothold in export markets with fresh-looking designs, especially Mazda which seemed to launch a new and interesting car every year since 1990.

Jack Telnack was the executive tasked with getting to grips with this play-it-safe mindset that seemed to be holding back Ford from its full potential. As Vice President Design for Ford, the buck stopped with Telnack when it came to creating interesting looking products. He was more than aware that things needed to change; the Ford board had commanded a fresh look, and he knew where to start and who to ask.

For decades Ford had operated a set of independent studios tasked with designing ‘different’ cars. There was Ghia in Turin, capable of turning out fully drivable one-off prototypes that challenged conventional thinking, then there were the Advanced Design studios in the UK, Germany, and Detroit – plus the ‘International’ studio where a US team created cars for other markets. It’s where the Ford Capri had been conceived back in the ’60s.

The International and Advanced studios, along with Ghia in Italy, were under the direction of an appropriately named Scotsman, Tom Scott. He was noted amongst his designer peers for having an all-rounder’s grasp of things that eluded many of them. “He could understand engineering issues, loved aerodynamics and was able to come up with something novel and futuristic every time” recalls Patrick le Quément, the former head of design at Renault and a peer of Scott’s when they were at Ford in the early ’70s. Scott had created the look of the iconic beak-nosed Escort RS2000 during this era before moving to the US as chief designer at American Motors (Jeep) before rejoining his old boss, Telnack, back at Ford in Detroit.

Scott recalls the dilemma. “We had all this research telling us we needed to be different, but what did that mean? There was research everywhere with trends and ideas but the one thing I knew was that we couldn’t keep doing this oval grille theme any more, plonked on these jellybean cars that looked like a floating cigar.”

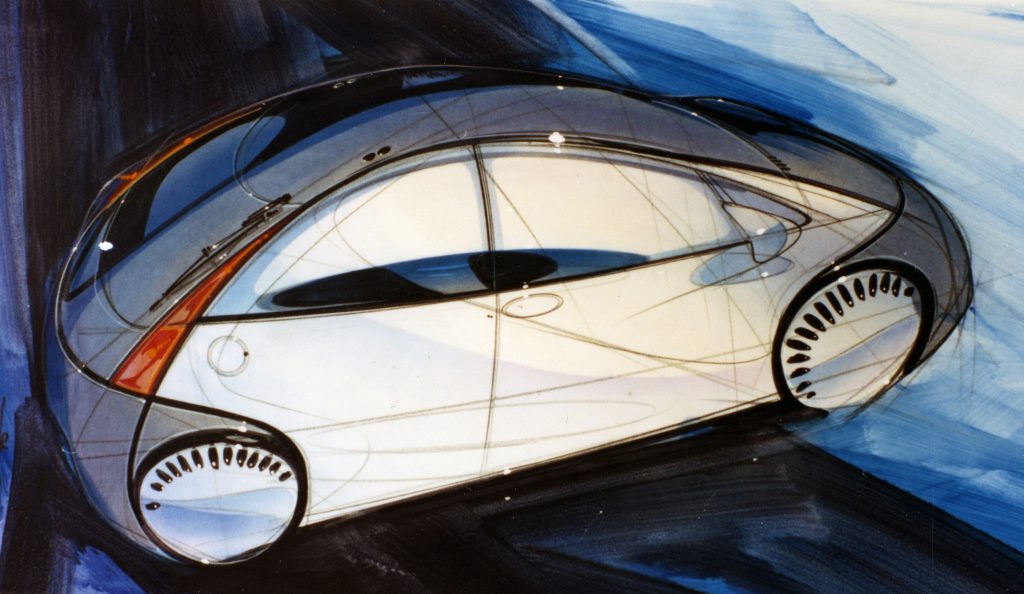

The Ka supermini had been conceived during ’93 and 94, and featured a then-novel riot of swooping lines, but they were not exactly a theme – merely a way to create a budget car that would stand out of the crowd. Designer Camilo Pardo in the Ghia studio had been exploring the theme more as a way of looking at a different style that expanded on the Ghia’s swoopy, bisecting lines, but there was no one single idea for a new Ford design language.

Tom Scott realised that the design team needed to be liberated – freed from the constraints of thinking about evolving an existing car. Forget about market research, focus groups, packaging and engineering constraints – and the dreaded cost-saving meetings with the bean-counters. The way forward was to dream up a new car that Ford didn’t make – something like a road-going racing car. That way the designers’ minds could be let off the leash, creativity would flow and exciting things would happen. Hopefully.

Scott knew that Ford needed to impress upon buyers that it understood tight body tolerances and precise shutlines – things that gave a sense of perceived quality to anyone walking into a showroom. The Japanese had mastered production tolerances that were lightyears ahead of the competition. Ironically, Ford had made good progress too but few gave the company or its cars credit for it.

For Scott, the answer was to create a ‘racecar for the road’., one with design language that screamed precision engineering from 10 paces away. If he and the team could perfect such a new look, they’d impress the Ford board, get the critics off their back and bring buyers into showrooms.

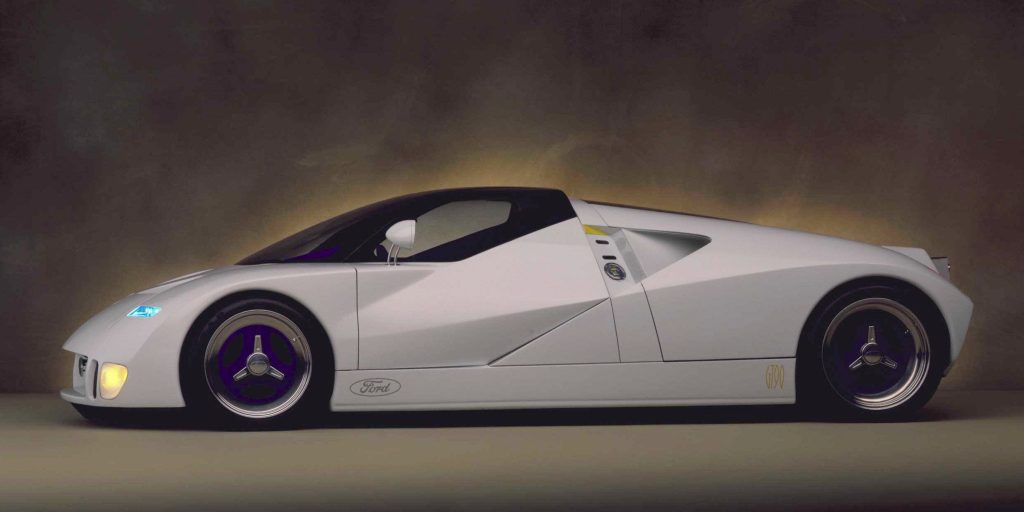

Chopping up a Jaguar XJ220

“I wanted to try something that looked like it was planted,” recalls Scott, “and demonstrate a new way of surfacing a car that wasn’t so endlessly rounded. I asked six designers for ideas, and Jim Hope drew a car that looked like a GT40 from the future. We needed a chassis for it to be a runner and I heard [then Ford-owned] Jaguar was struggling to sell its XJ220 supercar. So we had one sent over and chopped off the bodywork, lengthened the chassis and fitted an experimental V12!”

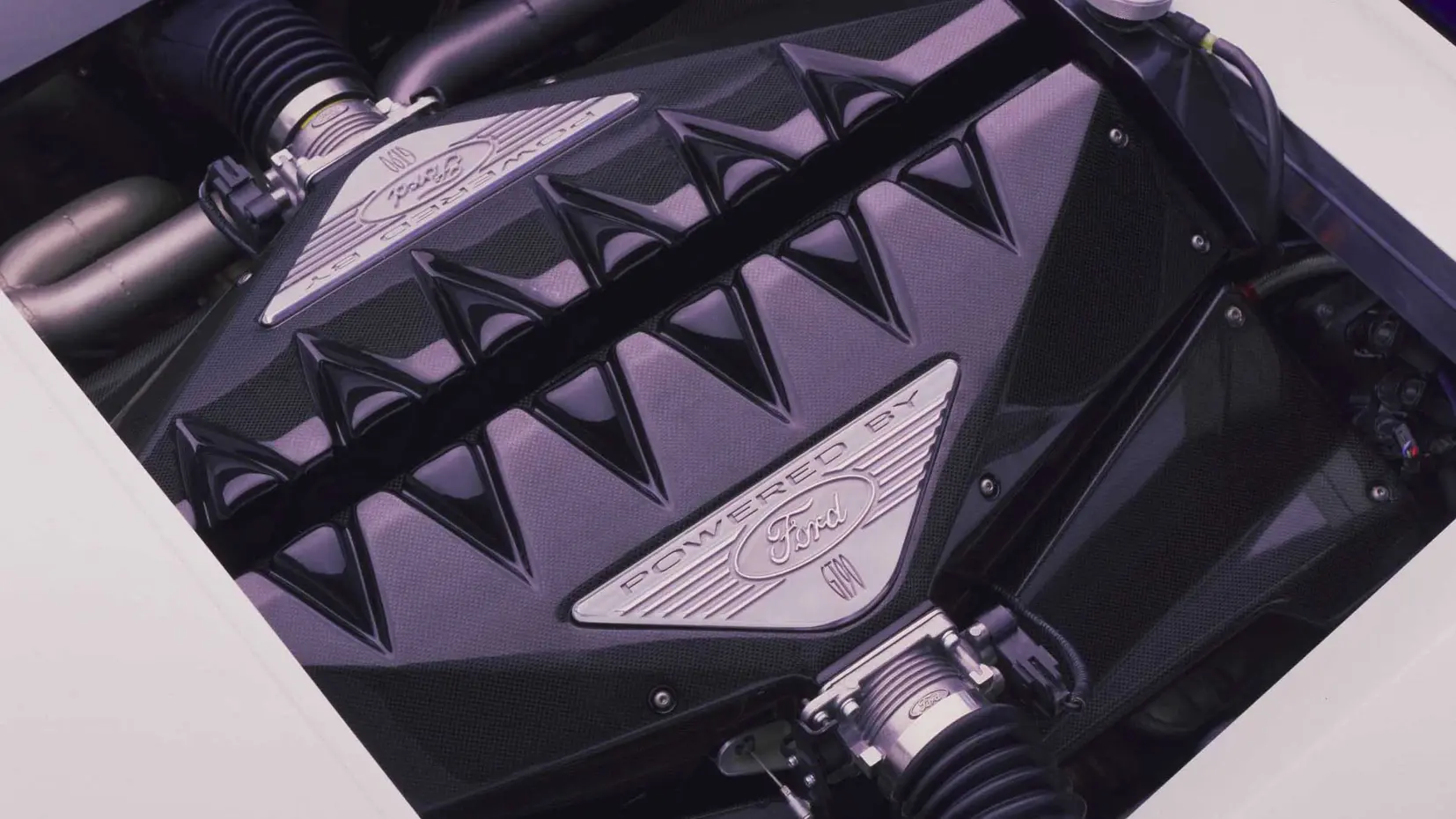

The engine started life in Ford’s Advanced Powertrain department as a theoretical exercise based on the new-for-the-nineties Modular Engine that was available as a 4.6-litre V6 in anything from the Mustang to the Prodrive-developed Rover 75 (it’s a long story) and as a 6.8-litre V10 in Ford’s full-size E-Series vans and F-Series pickups.

Engine designer Bob Natkin took one half of the new V8, beam-welded it to a V8 block, and got the cobbled-together V12 running in a Lincoln Town Car. And there it would have stayed had John Coletti, the engineer that kept the Mustang going, not heard about it.

John was running SVT (Special Vehicle Team), the specialist group that created Ford’s hotrod US models and the British SVE (Special Vehicle Engineering) group. Unlike their counterparts in Essex, the US-based SVT team were expected to not just engineer their vehicles but sell and market them too. They had tried ten years earlier to create the GN34 supercar to challenge Ferrari, but this time Coletti aimed a little lower; to make a one-off runner with no intended production role.

He tasked Fred Goodnow, SVT’s Engineering Manager, to mate the Jaguar chassis with Jim Hope’s edgy-looking bodywork and a quad-turbocharged version of Natkin’s 5.9-litre V12 making 720bhp – enough to beat the McLaren F1 that had set the world speed record for a production car just a few years earlier.

Coming up with a name for Ford’s new supercar was easy. The GT40 had been named after the Le Mans winners, and was then followed up a few years later with a stillborn successor, the GT70. Four drivable roadgoing GT70s were made but the mid-engined car lacked the race-winning chassis of its namesake. Nonetheless, the GT-letter dynasty had been established in the ’70s and here was the latest in the line, so GT90 it was – complete with gloriously entertaining tyres with the GT90 lettering hand-cut into them as treads.

Scott recalls that the dramatic-looking machine initially wasn’t well-received either by Ford’s senior management or the Detroit press. Things changed when the wider public and international press saw it. They were transfixed by the riot of triangles, even though Scott’s hope was that people would be more interested in the taut surfaces that created the sharp edges, rather than the outline shapes themselves.

People started asking Ford’s Global Vice President of Design, Jack Telnack, about this new style: was it the future? Jack’s response was that future Fords would have New Age Edge, he says. “Then I just shortened it to New Edge”.

Could the GT90 become a production car?

The GT90 caused such a stir that Ford’s senior management – naturally with Coletti’s encouragement – started looking at ways to make the car more than a statement of intent. Fred Goodnow, project manager for the GT90, even went so far as to tell Jeremy Clarkson, that given a two to three year development program, “there’s no doubt that we could build a car that would be fully competitive” and even “better” than contemporaries from McLaren, Bugatti and Ferrari.

But this is where the problems started…

Although Ford had a design hit on its hands, the car Scott had conceived was intended more to create new design-thinking than to be a halo-car for Ford. It was a one-off, shaped and engineered without so much of a thought about how a two seat, quad-turbo V12, 720bhp Ford supercar could be turned into a production reality.

Thoughts turned to tearing down more Jaguar XJ220s but that was uneconomic. The idea needed rethinking. Bob Natkin had developed another V12 based on Ford’s V6 Duratec engine that would be supplied to Aston Martin, yet rather than being a practical solution it presented a political problem. Using that engine and taking the blue oval brand into the territory of exotic-engined, six-figure supercars was where the Ford-owned Aston Martin brand belonged. If the executives approved such a plan, they’d effectively be competing with themselves.

And so it was that this sensational supercar remained a one-off. It had served its purpose, firing up the imagination of a disheartened design team, and ultimately influencing acclaimed cars such as the Ka, Puma, Focus, and even the Cougar. But anyone hoping to see Ford once again slap down Ferrari would be disappointed. For better or worse, that job was left to Aston Martin.

Still, the flame that burned so bright around the GT90 didn’t die entirely. Its challenger spirit reinvigorated thinking in the corridors of power at Ford. The company needed a flagship supercar, and it would look to its past for the answer.

Camilo Pardo, who had created some of those edgy design sketches while at Ghia, was working for Ford in the US in the early 2000s – at the peak of retromodern design, when BMW gave us the Z8 and the Mini. New Edge had fallen out of fashion by now but the spirit of GT90 was still alive. John Coletti was given the task of engineering a mid-engined GT and Pardo the job of creating its retro looks. The new GT40 Concept, revealed in 2002, looked like little more than an update of the old road-going racer. But if it hadn’t been for the one-off GT90 in between, Ford might have lost that lust for a life-affirming supercar and killed off its supercar dynasty entirely.

For that, we should be grateful.

***

You can get a Hagerty-exclusive discount of 10 per cent – plus free UK P&P – off each of the two volumes of Steve Saxty’s Secret Fords books at stevesaxty.com. Use the coupon code HAGERTY10 at checkout.

Read more

The fastest Ford the world never saw

What could have been: The hot Healey Fiesta

The secret story of Ford’s four-wheel drive Capri

Why does everyone keep going on and on about so called “Supercars”? apart from posing at a crawl along a main road in the south of France or the fashionable part of any city they are totally useless, uncomfortable, and impracticaable, certaily they are nice to look at such as a piece of sculpture , but as a practical means of transport just useless and as for anyone over five foot tall , forget it

Wouldn’t look out of place if released today. Still looks mighty fine to me.